Fig.1

Dennis Oppenheim

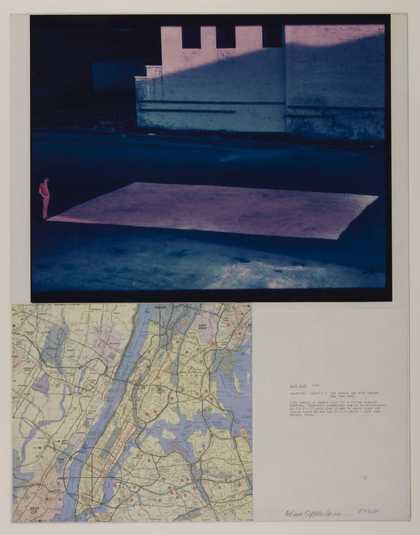

Salt Flat 1968

Photograph, map and typescript on board

711 x 559 mm

Tate T01773

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

Standing at one corner of his 50 x 100 ft (15 x 30 m) rectangle of baker’s salt in a large colour photograph in Tate’s version of Salt Flat 1968 (Tate T01773; fig.1), Dennis Oppenheim looks back in the direction of the camera, head turned as if something or someone has just drawn his attention. Hands thrust down and slightly forward in his pockets, arms just crooked at the elbows, the fleetingness of Oppenheim’s glance and posture captured in this photograph is appropriate to the sculpture laid out before him, as its pristine edges were also on the cusp of transformation and imminent disappearance.

![Dennis Oppenheim, Salt Flat 1969 [1968]](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig.3oppenheimsaltflat1969edit.width-420_HIMhEL3.jpg)

Fig.2

Dennis Oppenheim

Salt Flat 1969 [1968]

Private collection

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

Situated in a parking lot on the west side of Manhattan at the intersection of 6th Avenue and 25th Street, Salt Flat’s crisp, rectangular composition is a reminder of the conventional formats of painting and photography invoked by contemporaneous works by the artist, including his well-known Reading Position for Second Degree Burn 1970 (Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin), in which Oppenheim left the mark of another white rectangle on his own chest by carefully controlling a sunburn.1 But in even less time than it would take for this sunburn to fade, Oppenheim’s arrangement of salt in New York City would dissipate through the combined actions of wind, rain, and the daily traffic of cars and pedestrians. While the viewer is not given access to such views of Salt Flat dispersing, it is notable that Tate’s particular version of the documentation of this work pairs only the single photograph at hand with a map of Manhattan indicating the piece’s location. Other versions of Salt Flat that Oppenheim created for exhibition feature additional photographs that show the salt being pushed and arranged by the artist (fig.2). That is, while the form of Salt Flat invoked by Tate’s photograph of the work suggests a rather static object, identifiable as much by its clearly visible proportions as by the ominous crosshairs Oppenheim inscribed on the map of Manhattan, more decidedly unstable processes of creation and dissolution are integral to the piece. Consider, for instance, two further iterations of Salt Flat that Oppenheim describes in the typewritten text he attached to the documentation, which states that ‘Identical dimensions are to be transferred in 1’ x 1’ x 2’ salt lick blocks to ocean floor off Bahama coast XX and dug to a 1’ depth – Salt Lake Desert, Utah’. Although these alternative iterations of the work were never realised, they indicate that in the very conception of Salt Flat there was an even greater emphasis on processes of dissolution and absorption than appears in the salt that Oppenheim did lay out on a patch of asphalt in New York City.

Counter to the tendency within post-war art history to associate ‘process art’ of the late 1960s with predominately additive or accumulative actions, Oppenheim in fact spoke on several occasions during this period about the importance of the subtractive aspects of process.2 Talking with artist, curator and publisher Willoughby Sharp in a now iconic group interview printed in the inaugural issue of Sharp and artist and writer Liza Béar’s experimental art magazine Avalanche in autumn 1970, Oppenheim addressed this approach by describing his initial foray into working outdoors:

Sharp: Dennis, how did you first come to use earth as sculptural material?

Oppenheim: Well, it didn’t occur to me at first that this was what I was doing. Then gradually I found myself trying to get below ground level.

Sharp: Why?

Oppenheim: Because I wasn’t very excited about objects which protrude from the ground. I felt this implied an embellishment of external space. To me a piece of sculpture inside a room is a disruption of interior space. It’s a protrusion, an unnecessary addition to what could be a sufficient space in itself. My transition to earth materials took place in Oakland a few summers ago, when I cut a wedge from the side of a mountain. I was more concerned with the negative process of excavating that shape from the mountainside than with making an earthwork as such. It was just a coincidence that I did this with earth.3

Oppenheim’s observations here about ‘negative process’, over and above that of more familiar tropes of earthbound materiality, site specificity or land-based topography in the reception of early land art, suggest that he was working through a different set of aesthetic concerns than those of contemporaries such as Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson, with whom he was grouped in the Avalanche interview. Rather than emphasising physical qualities of earth and place, Oppenheim instead seized upon their elimination.

Oppenheim had also spoken about this position in an interview with Patricia Norvell conducted the previous year:

Oppenheim: Another aspect of this [outdoor sculpture of the late 1960s] that I think is very influential to new sculptors is the fact that you are making something by taking away rather than adding. And this seems to have borne many fruits, pieces involving removals.

Norvell: You mean pieces that are on a grander scale. Because sculpture used to be that way – with stone carving.

Oppenheim: … I don’t think artists have ever been concerned with removals or the residue of an act. And although a lot of sculpture, a lot of technique, involved taking away, it wasn’t concentrated upon, it wasn’t focused upon as being a piece.4

These comments indeed confirm that Oppenheim had identified a seemingly contradictory aspect of early land art: that despite land art’s purported investment in the living, accumulative qualities of growth and change in outdoor sites, many of its sculptural processes in fact involved deletion rather than addition. Different approaches to negation have a significant place in post-war art, whether in Guy Debord’s call to ‘Never Work’ in graffiti on a Parisian wall in 1953, Lee Lozano’s lengthy, if not ongoing, action Dropout Piece (begun 1970), or NO!art, the anti-art movement founded in New York in 1959.5 But Oppenheim’s unusual approach to negation addressed it specifically through ‘process’, a notion vital to postminimal and body art of the 1970s. On the one hand this move might not register as particularly surprising, as Oppenheim was seeking to bridge ‘negation’ and ‘process’ as two prominent aesthetic concerns of the post-war period. On the other, his comments and the body of work he produced in connection with them create an apparent contradiction in generating the amalgam of ‘negative process’, the former invoking refusal and the latter engagement in their conventions of meaning in post-war art.

What is a process that negates itself (and perhaps more)? Taking Salt Flat as a point of departure, we will examine four approaches to this question that Oppenheim pursued during the period 1967–70, each proving, in its own way, both inadequate to and instructive about the prospect of realising a truly negative process.

Excavation

Fig.3

Michael Heizer

Double Negative 1969–70

Two gouges in the rock of Morton Mesa, Overton, Southern Nevada

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

© Michael Heizer/Triple Aught Foundation

Oppenheim’s first foray into a negative sculptural process was also his first earthwork: the wedge-shaped hole he cut into a hillside in Oakland in the summer of 1967 to create Oakland Wedge. While it predates Heizer’s use of negative space in his iconic earthwork Double Negative 1969–70 (fig.3) by at least two years, the relative obscurity of Oakland Wedge compared to earthworks such as Double Negative arises in large part from the fact that no one else aside from Oppenheim has ever given any account of Oakland Wedge. Although slowly crumbling, Double Negative remains openly accessible to anyone in the vicinity of Las Vegas with a map and a vehicle, and was substantially photographed by the famed land art documentarian Gianfranco Gorgoni. By contrast, there is no photographic evidence of Oakland Wedge, and if Oppenheim ever showed it to anyone else, those spectators have yet to write about the experience. As a result, Oakland Wedge is a real excavation that exists in a highly conceptual state of being, invoked only through word-of-mouth and the imagination. For Oppenheim, it also became a symptom of something that he spent approximately three years trying to diagnose, a diagnosis that encompassed testing the limits of minimalist sculpture and ended with an attempt to insert his work directly into the operation of social and biological systems.

Systems is a subject to which we will return below. Regarding minimalism, Oppenheim has spoken about the importance in the late 1960s of getting around a certain exhaustion or impasse that had arisen in minimalist sculpture, or what he called ‘object-oriented art’.6 By cutting a geometrically bounded shape into a hillside, Oppenheim both created the ‘impression’ of the kind of objects associated with minimalism and at the same time appeared to empty them out, to generate an operation for making an artwork that would leave a vacuum in place of the present object. However, as Oppenheim came to realise in his subsequent analysis of this operation, his negation of the minimalist object instead created a problem of boundaries. According to the artist, ‘with that indentation or that hole, there became the question of where exactly is the object. If that hole is an object or if a hole is an object, then is it the indentation or the peripheral? And by scribing into land, where does your piece leave off and where does it begin? … I mean, is your piece a large area of land with a hole in it or is it a hole?’ To this series of questions he would add, ‘Is your piece the entire globe with a hole in it? I’m sure it is.’7 The dissemination of extra-terrestrial photography in the late 1960s had in fact led to a view of the earth as a solid, spherical object akin to a minimalist object suspended in the black void of outer space.8 Within such a framework, Oppenheim’s attempt to negate the minimalist object through a process of excavation instead invoked the presence of precisely this kind of object on the largest scale imaginable.

Inversion

Fig.4

Dennis Oppenheim

Sterlized Surface. Glass., Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris 1969

Private collection

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

A second approach to negative process appears in Oppenheim’s practice through a series of works he created using actions that invert or reverse a state of order. In his published notebook entries from April 1969, for instance, he lists various of these self-negating operations, such as ‘reverse processing, … ingoing/outgoing, … [and] body/antibody’.9 This list also includes notes for various works involving ‘sterilization’, which Oppenheim realised in both Paris and Milan during the late spring and early summer of 1969, while in Europe for solo exhibitions at Galerie Yvon Lambert and Françoise Lambert, respectively. For Sterilized Surface. Glass. at the former (fig.4), Oppenheim employed the following three-part process:

Stage #1: Application of commercial glass Cleaner

Stage #2: Removal of Cleaner

Stage #3: Sterilized Surface.10

While adopting the everyday task of cleaning a window as an artistic activity, Oppenheim’s piece took on other important dimensions. The specific ‘commercial glass Cleaner’ that he selected temporarily blocked a view inside the gallery from the street, thereby calling attention to the accessibility of the gallery as a commercial and public institution in a manner closely related to contemporaneous works by European artists such as Yves Klein and Arman and the American Michael Asher. But rather than focusing on Sterilized Surface as an early example of institutional critique, we might instead pause upon its conception of ‘sterilization’. For in related works, such as Sterilized Infected Zone 1969 and Infected Zone 1969, Oppenheim made explicit that sterilisation is the condition opposite to that of infection, meaning that his act of cleaning the glass at Yvon Lambert not only highlighted the visibility of the gallery’s interior from the street, but also the status of this glass barrier as either a clean or a dirty layer of transition between exterior and interior. In deeming this act one of sterilisation, Oppenheim’s work indicates that in fact ‘Stage #1’ of the piece is not the ‘Application of commercial glass Cleaner’, but is instead the conceptual determination that the glass surface outside Yvon Lambert was not sterile. Thus, rather than simply a performative (and practical) act, the application and removal of glass cleaner is an inversion of the previous state of this glass, an infected surface made sterile. That being said, Oppenheim’s small deed did not substantially affect the hustle and bustle of life on the streets of Paris. Almost immediately, this surface would have once again been exposed to the polluted particulate of Paris’s atmosphere, influenced in no small part by the very vehicles captured in the lower left corner of the three photographs depicting Sterilized Surface. Glass. While this return might suggest that a negative process had been achieved – an ‘infected’ surface being ‘sterilized’ only to become ‘infected’ once more – the opposition of these terms that Oppenheim introduced for naming and understanding the simple exterior of Galerie Yvon Lambert do not disappear with the accumulation of soot. On the contrary, these terms set in motion an ongoing interchange between cleanliness and dirtiness. And although the specific kind of movement that results from concepts being opposed to one another as a kind of dialectic is one of the grand and unresolved questions of modern philosophy – taken up in differing ways during the very period of Sterilized Surface by contemporary artists such as Robert Smithson and philosophers such as Theodor Adorno – the basic insight of such dialectics is clear: that opposition does not create erasure so much as enduring cycles of thought.11 In the case of Sterilized Surface, it is a cycle that continues in contemporary discussions about the relative contamination and sustainability of life in urban environments.

Environmental erasure

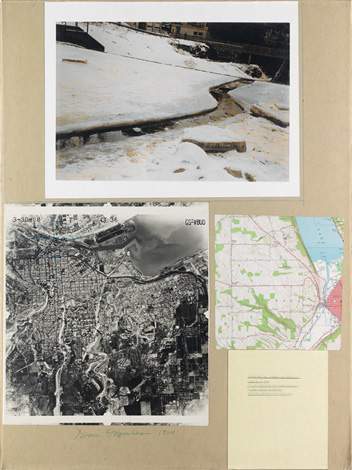

Fig.5

Dennis Oppenheim

Accumulation Cut 1969

Private collection

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

A related procedure to that of Oppenheim’s inversions arose in the artist’s attempts to intervene in outdoor environments, anticipating that his actions would be countered by the climatological conditions of such environments. Encompassing works created using snow and ice along the US–Canada border, as well as pieces in the ocean off the coast of Trinidad and Tobago, this impulse is perhaps best distilled in the Accumulation Cut (fig.5) that Oppenheim executed on Lake Beebe in Ithaca, New York, in 1969 as part of Willoughby Sharp’s Earth Art exhibition. Originally titled Lake Beebe Ice Cut, Oppenheim’s earthwork consisted of a channel of open water that he cut into a frozen lake, using a chainsaw to penetrate the ice initially and a broom to sweep loose chunks over a frozen waterfall at the lake’s edge. By its less place-oriented and more conceptually suggestive nomination of Accumulation Cut, this work invokes two opposing operations: the first, a cut or removal made by the artist, and the second, an accumulation enacted by the environment wherein Oppenheim’s freshly sawn channel of open water would refreeze and disappear. Although Accumulation Cut did indeed seem to vanish – in that under the wind, precipitation and freezing temperatures of Ithaca’s weather, it was no longer visible to the naked eye within a matter of days – one of the fundamental insights of recent climate science is that no such action on the planet, whether great or small, is ever completely expunged from the macroscopic conditions of the earth.

As has been noted of much larger earthworks such as Heizer’s Double Negative, the ‘accumulation’ of Accumulation Cut includes not only the ice crystals on Lake Beebe, but also the exhaust from the gasoline engine of Oppenheim’s chainsaw, the carbon footprint of the artist’s travel to Ithaca from New York City, and so on.12 In short, the fantasy enacted within Accumulation Cut of environmental erasure is but one piece of a larger myth about the natural balance and self-correction of environments that has persisted in an alarming fashion well into the twenty-first century, despite being contradicted by the overwhelming evidence of the climate data during that same period.

Systems breakdown

Fig.6

Dennis Oppenheim

Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop 1969

4 photographs, colour, on paper on board

1651 x 4064 mm

Tate T12402

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

With the publication of the critic Jack Burnham’s essay ‘Systems Esthetics’ in September 1968, the notion of art operating within or creating systems assumed an especially prominent role in the imaginary of post-war art.13 While artists such as Hans Haacke had been producing works that operated as self-sufficient systems for a number of years, Burnham’s contribution was to note the importance of artists who did not generate independent systems, per se, but whose work instead intervened within existing systems, whether ecological, social or institutional. As Oppenheim began to address such systems of time, geography and agriculture in a number of works in 1968–9, it is only fitting that Burnham’s next major piece of criticism, ‘Real Time Systems’, would single out an ongoing piece by Oppenheim in the Netherlands named Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop 1969 (fig.6). For the first part of this work, Oppenheim planted a field of wheat in the town of Finsterwolde according to the pattern of the roads leading to the field. Following the maturation of this wheat, Oppenheim next proceeded to harvest only a select portion of it, defined by the lines left by the combine harvester between the two diagonals of the field, harvesting in a pattern that created a large ‘X’ across the expanse of the wheat field. He then followed this symbolic gesture of negation with its actualisation by keeping the harvested wheat from entering the market, thereby attempting to break down the circuit through which the bio-industrial system of agriculture interfaces with that of commodities markets.

In his account of this work, Burnham describes it as ‘a broad use of interacting ecologies’, suggesting that the ‘cancellation’ of the wheat harvest had not fully negated its preceding system of agriculture, but instead shifted its network of relationships into a different vector, namely the art world’s systems of information and display.14 In fact, Oppenheim included bags of the raw, harvested wheat in addition to his typical use of photographs, maps and textual description when displaying Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop, while the remainder of his crop was left to wither, unharvested, in Finsterwolde. Consequently, in this final strategy of negative process, Oppenheim did not set out to erase the existence of the wheat itself, but only that of the wheat’s circulation as an agricultural good. To explain this move, Oppenheim provided the following rather elliptical statement to Burnham:

In ecological terms what has transpired in recent art is a shift from the ‘primary’ homesite to the alternative or ‘secondary’ homesite. With the fall of the galleries, artists have sensed a similar sensation as do organisms when curtailed by disturbances of environmental conditions. This results in extension or abandonment of the homesite.15

Situating his work within larger turns in both ecological theory and artistic practice, Oppenheim creates an analogy between land artists’ move from the studio to the land and that of Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop’s displacement of wheat from foodstuff to artwork. In each case, the system that sustains artistic production and agricultural production, respectively, has been relocated from what Oppenheim identifies as an initial or ‘primary’ homesite to a new or ‘secondary’ one. This statement is confounding, however, in that the ‘crop’ of Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop is not ‘cancelled’ at all, but instead has been recalibrated from one system of meaning and circulation to another – from that of growing and selling raw commodities to that of the contemporary art world. Thus, rather than negating the system through which this harvest of wheat might otherwise exist, Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop instead enacted a transfer between the kind of ‘interacting ecologies’ described by Burnham in ‘Real Time Systems’.

Salt Flat and dematerialisation

Returning to Salt Flat, we might note two aspects of the piece that come into tighter focus through this investigation of Oppenheim’s various attempts at creating negative processes. Firstly, while Salt Flat does not exemplify Oppenheim’s tactics of either excavation or inversion, it might be productively read through his tendencies to invite environmental erasure and create systems breakdown. Of the former, we might recall how fleeting the rectangular arrangement of salt in Manhattan would have been, where the environment that disrupted the clean edges of Oppenheim’s array of salt was not limited to the local weather but also included the social traffic of New York’s urban ecology. Regarding systems breakdown, Oppenheim’s distinction between the use of ‘baker’s salt’ in the New York version of Salt Flat versus the ‘salt-lick blocks’ in the other parts of the work that he proposed is a notable detail, since it indicates that the artist was thinking in terms similar to the displacement he created in Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop. Rather than transferring a crop into a different system of signification, however, Salt Flat displaces a raw, albeit antiquated, ingredient associated with the many local bakeries and pizzerias in the neighbourhoods in and around Oppenheim’s chosen parking lot in Manhattan, allowing it to be dispersed into the ecological system of the urban environment.16 Other works of this period, such as Reverse Processing, Cement Transplant, East River, NY, 1970 1978 (fig.7), in fact display all of the artist’s tactics of negative process, with the exception of excavation, within the same piece.

Fig.7

Dennis Oppenheim

Reverse Processing, Cement Transplant, East River, NY, 1970 1978

Tate T07591

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

Secondly, Salt Flat exemplifies the very kind of failed dematerialisation that typifies both Oppenheim’s attempts at negative process and the larger drive towards immateriality and effacement in art in the late 1960s. As coined by critics Lucy Lippard and John Chandler in an essay published in February 1968, dematerialisation described a means of counteracting the commodification of art by elevating the transience of ideas and processes over the material or object-bound qualities of art.17 Lippard, however, would reflect some two decades later that it had been all too ‘utopian’ to think that ‘artists who are trying to do non-object art are introducing a drastic solution to the problems of artists being bought and sold so easily, along with their art’.18 While it might have taken decades to drive home the point that nothing evades the market – even the conceptualist ephemera of Xerox copies and performance notes – Oppenheim’s various approaches to negation had in fact resolved this problem at the height of the dematerialist impulse. By exposing the particular inadequacies of excavation, inversion, environmental erasure and systems breakdown, Oppenheim’s work had tested and determined that, at a basic level, no process, whether financial, environmental or otherwise, ever truly dematerialises or ceases to exist.