The world is a sphere, and that’s our boundary, our physical boundary. So we grow out of the studio. We could just spend our life widening our boundaries until we’re faced with the fact that we are just a very small speck.

Dennis Oppenheim1

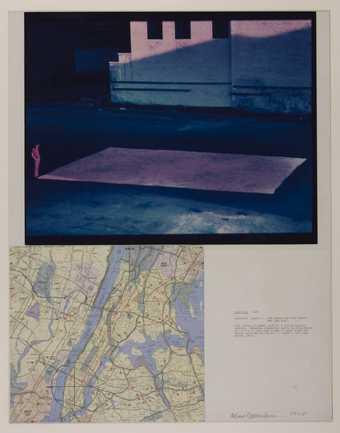

Fig.1

Dennis Oppenheim

Salt Flat 1968

Photograph, map and typescript on board

711 x 559 mm

Tate T01773

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

An extrapolation from the dirt to the planet earth – from the speck to the sphere – characterised Dennis Oppenheim’s engagement with the land. Starting in 1967, the artist created a suite of works that he called ‘transplants’. These works examined the elemental nature of the earth and the built environment, and their relationship to the institutions that governed society. This essay examines Oppenheim’s Salt Flat 1968 (Tate T01773; fig.1) as a key example of Oppenheim’s transplants, and considers the work’s relationship to the artist’s broader engagement with the land.

Salt Flat is fundamentally concerned with the dichotomies between empirical experience and conceptualisation that result from human interactions with the earth. At first glance the work seems rather uninspiring: a documentation showing an action that involved the presentation of a pedestrian material (baker’s salt) in the shadow of dirtied buildings off 6th Avenue in downtown New York City. However, the sheer quantity of salt – one thousand pounds (454 kilograms) spread over 5,000 square feet (450 square metres) – and its carefully outlined placement in a location never intended for it, create a surprising conceptual relationship between material, site and meaning.

Land art created by Oppenheim and his contemporaries has traditionally been defined as ‘site-specific art’, as the works intentionally involve the site of their creation and exhibition as part of their content.2 However, the category of site-specific art ignores the extra-referential nature of much land art, many examples of which refer both to specific sites and to a place beyond such immediate locations. I propose an alternative model for understanding these works: through Michel Foucault’s notion of the heterotopia – a site that converges with and inverts conceptually linked spaces. The heterotopia does so via cognitive connections or referents of time and space, which indicate both the work’s actual site and other associations. Foucault argued that heterotopias engage space polemically: ‘Either their role is to create a space of illusion that exposes all real space, all the emplacements in the interior of which human life is enclosed and partitioned, as even more illusory … Or else, on the contrary, creating another space, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is disorderly, ill construed and sketchy.’3 The societal functions that heterotopias represent can become unsettled because of the cognitive dissonance produced by such affiliations. Salt Flat presents various referential links (between the sites of action and reception; of the metropolis and nature; of decay and preservation) in order to incorporate other sites into the work conceptually.

Land art as heterotopia

Art historian Suzaan Boettger was the first to posit the heterotopia as an art historical model, arguing that early earthworks were ‘counter- or anti-monuments’ and that land artist Robert Smithson’s photo-journalistic snapshots of New Jersey (1967–8) and Claus Oldenburg’s ironic Placid Civic Monument 1967 in New York’s Central Park were ‘fundamentally mixed’ counter-sites that amounted to ‘inversions of art in public places’.4 Foucault had advanced the idea of the heterotopia in 1967, during a time of immense cultural tumult, when neo-avant-garde artists turned to the land as a radical sculptural material amid a bevy of sociopolitical upheavals and the dawning of a new ecological consciousness.5 Within this framework, Oppenheim’s transplants served a twofold purpose: firstly, they employed the land as medium, engaging with new social ecologies and broadening the range of artistic sculptural materials; secondly, they turned to other, marginalised spaces, highlighting the normative role of the artistic establishment and, in doing so, further eliding the putative dichotomy between art and life. Essentially, Oppenheim worked with the land and its elements in order to posit them as culturally coded and institutionally defined materials.

Oppenheim first conceived of Slat Flat as a transplant and intended to place blocks of salt on the ocean floor in the Bahamas and to remove a similar amount of salt from the Great Salt Lake in Utah.6 Unpublished writings in the artist’s notebooks from this time suggest an even further integration of the work into a series of transplants, where similar actions would be produced in negative on the forest floor as ground excavations.7 Oppenheim’s extant transplants exhibit many formal commonalities in their documentations: photographs fill the top half of the work; pseudo-scientific text sits beneath the photographs; and aerial maps complete the bottom half.

Fig.2

Dennis Oppenheim

Decomposed Whitney, Whitney Annual 1968 1968

Portland cement, silicates, mineral aggregate, steel, gypsum, hydrous calcium sulphate, various woods, granite, slate, bronze, sodium phosphate, potash, lime, lead and aluminium

915 x 4570 x 2130 mm

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

The self-reflexive nature of Salt Flat reinforces the heterotopic associations within the work, suggesting parallels to contemporaneous examples by Smithson and Walter de Maria. Salt Flat emerged with a cluster of works that tended towards an investigation of earthen elements, notably seen in Decomposed Whitney, Whitney Annual 1968 1968 (fig.2), which consisted of pulverised powder from elements that comprised the actual physical structure and building materials of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. For Salt Flat, the relationship to the earth was not as overtly site-specific and the key element was a simple and readily available product: salt. This element existed first as a purchased commodity which was then repurposed as an art object (through photographic intervention). Importantly, this salt lacked the cultural value traditionally imparted to works of art. To this point, critic Thomas McEvilley considers the recurrent act of ‘designating’ a non-art object as a work of art the ultimate readymade gesture in Oppenheim’s work.8 However, Oppenheim moved beyond Marcel Duchamp’s self-reflexive critique of art by engaging with the broader social conditions of the work, those that defy the limits of the art object or the art institution.

Similarly, Oppenheim’s works required physical labour while Duchamp’s were cerebral. Art historian Dalia Judovitz argues that by dint of Duchamp’s conceptual act, his works entered directly as capital into the artistic system, without maligning the wealthy patrons who made the system possible and instead reaffirming their control of that very system.9 Oppenheim, on the other hand, was painfully aware of the financial stresses of creating ambitious, large-scale works of art without a patron and without guaranteed financial backing. While contemporaries including Smithson, de Maria and Michael Heizer secured the largess of visionary patrons, Oppenheim worked largely within the traditional gallery model.10 He primarily financed his own work, which led to projects determined by the availability and cost of given materials or spaces, and he filled his notebooks with unbalanced ledgers and details of material costs more befitting a landscaping contractor than an artist. The self-funded nature of his practice was felt when Oppenheim was unable to realise the component of Salt Flat that aimed to cover the ocean floor of the Bahamas with salt; instead, he marred the picturesque locale, setting fire to a reddish die in a path he traced through the ocean as part of Two Ocean Projects 1969. Whereas Salt Flat highlighted the run-down metropolitan milieu of 6th Avenue in Manhattan, setting alight idyllic ocean waters undercut notions of aesthetic beauty in nature and, as Oppenheim described it, imbued the land with ‘some form of violence’.11

Mapping heterotopias

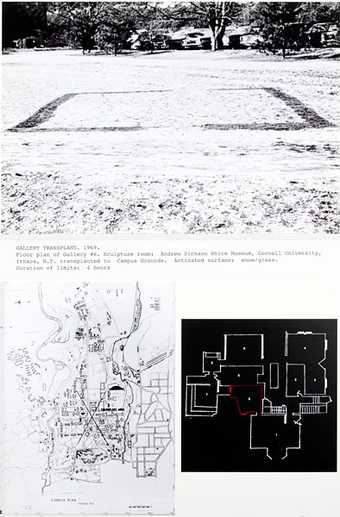

Fig.3

Dennis Oppenheim

Gallery Transplant 1969

Floor plan of gallery 6, sculpture room, Andrew Dickson White Museum, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, transplanted to campus grounds

Activated surface: snow/grass

Duration of limits: 4 hours

Black and white photograph, hand-stamped topographic map and hand-marked photographic floor plan

1524 x 1016 mm

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

While Salt Flat never found its intended realisation as a tripartite series, Oppenheim did execute and document a closely related series of transplants, the Gallery Transplants begun in 1968 (fig.3). For these Oppenheim literally enacted the primary stages of constructing an art institution – making a physical space for the display of art and creating art to fill that space. To create a Gallery Transplant, Oppenheim shovelled dirt or snow to form the outline of a museum floorplan at an outdoor site; indexed the action via photography; constructed a collage of the photographic documentation alongside aerial maps and text on a panel; and exhibited the collage in the original gallery space that was used as the blueprint for the outdoor gallery outline. It is in the Gallery Transplant works that the formulation of Foucault’s heterotopia begins to take hold by addressing the ‘sanctified cultural space’ of the museum.12 At their most basic level, the transplants replicate how art institutions are constructed – by actual physical labour and by accumulated works of art.

Maps feature prominently in Oppenheim’s land art from the late 1960s, forging a temporal relationship between the site of physical action and the action’s photographic representation. Art historian Larisa Dryansky identified Oppenheim’s use of maps as tantamount to photography, as they joined otherwise disconnected and discordant sites. She argues that artists in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, especially Oppenheim, used maps to create a sense of ‘displacement’ that contributed to the dematerialisation of art.13 Oppenheim’s maps in the Salt Flat series (he created numerous versions of Salt Flat, often using different photographic records of his action coupled with similarly styled maps) united two disparate ‘sites’ – the physical one and its photographic or cartographic representation – which exemplifies the foundational principal of a heterotopia.

Oppenheim – who was raised in California and moved to New York, and was thus himself a transplant – used maps to anchor the viewer’s sense of location in his works. On a personal level, the ubiquity of maps in Oppenheim’s work could be thought of as a grounding mechanism for the artist’s own personal relocation. In a 1969 interview he stressed the importance of using maps while planning sites: ‘I study a lot of contour maps, quadrangle maps, and I walk around the area.’14 The physical process of altering the land – be it by digging in the raw earth, branding the landscape, or depositing a significant amount of salt onto its surface – provided the literal and conceptual basis for Oppenheim’s earthworks, which he located with maps, suggesting a referential continuum between the land/site, the photograph and its cartographic representation.

Oppenheim continually reinforced the spatial relationship between the photographs in his collages and their (ostensible) location on the maps that accompanied the indexical documentation. The juxtaposition of the photograph and map in Salt Flat serves to contrast the actual, physical space where the action occurred and a conceptual location that exists within a defined system (in this case the grid of Manhattan). The map of lower Manhattan is not oriented on a vertical grid axis, a style that would have been widely recognised from subway maps at the time, but as a topographic map of the greater southern New York metropolitan area. The map in Salt Flat recalls aerial photography. The black circle imposed on it resembles a target from a rifle sight, creating a focal point. Similar targets recurred often in Oppenheim’s work; he even went so far as to inscribe crosshairs and ‘X’s on the earth as the basis of works like Branded Mountain 1969 (private collection), Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop 1969 (Tate T12402) and Reverse Processing, Cement Transplant, East River, NY, 1970 1978 (Tate T07591).

Other heterotopias: Salt Flat in context

The physical substance – the salt that Oppenheim laid out in Manhattan – suggests a link between Salt Flat and the sociopolitical milieu of Vietnam. The work finds its namesake in the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, one of the least hospitable spaces on the earth and an area that was used for bombing and military training exercises during the Second World War. Salt Flat, located underneath crosshairs on the map in the work, performs a mimesis of this uninhabited space. Oppenheim surveys the aftermath of a post-apocalyptic world: long shadows fall across a clear, flat plane of hostile earth, set against the emptied backdrop of dirtied buildings.

The curator and avant-garde publisher Willoughby Sharp captured the visceral experience of being present while Oppenheim created the site-specific component of his works. He described this in a 1969 catalogue: ‘The spectator has to experience the different stages of the system if he wants to experience the whole work … such works [cannot] be fully understood through single photographs in the manner of traditional painting or sculpture.’15 However, Salt Flat as a finished work (the photograph, text and map) belies its raw, physical nature – the action of spreading one thousand pounds (454 kilograms) of salt in a dilapidated parking lot in lower Manhattan. This dichotomy suggests that the work encompasses both a physical act and an exhibited documentation. The contingent nature of Salt Flat suggests an important aspect of Oppenheim’s early practice: he would often change a previously planned work as it was being created in order to take advantage of new materials or situations in real time. These contingencies raise important considerations of temporality and place, revealing the works’ durational component and physical constraints, and places into doubt whether the work ever qualifies as truly finished.

Transforming nature

Fig.4

Dennis Oppenheim

Reverse Processing, Cement Transplant, East River, NY, 1970 1978

Tate T07591

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

Oppenheim repeatedly drew attention to the decrepit, anti-bucolic nature of the urban landscape in works related to Salt Flat. For another work in Manhattan, Reverse Processing, Cement Transplant, East River, NY, 1970 1978 (fig.4), Oppenheim marked with white cement ‘X’s six open shipping containers on the East River that were filled with sand and gravel. Reverse Processing emphasised the chemical changes that could occur to the land, in this instance its transformation into concrete (which then would become the foundational elements of buildings). Oppenheim spoke of buildings as an extension of the land itself, remarking that a building’s floors ‘could be used as a strata the same way we would view a core sample from the Earth’.16 Salt Flat, Reverse Processing and the Gallery Transplant series all emphasised a reversion to an original state prior to human intervention. Salt Flat would return to the expansive, dried up crystalline floor of Lake Bonneville; Reverse Processing returned to the elemental building blocks of skyscrapers where, in the artist’s words, the ‘end product is returned to [its] location of a preliminary processing stage’; and the Gallery Transplants returned to the unaltered land as medium, on and from which museums might be constructed. By means of Oppenheim’s interventions into these spaces, each of the works referred heterotopically to sites beyond their immediate setting.

Fig.5

Dennis Oppenheim

Buried Novel 1969

Textual record published in Seth Siegelaub (ed.), One Month (or March 1969), New York 1973

During a period of renewed interest in nature during the mid-1960s, Oppenheim repeatedly grappled with the impact of humans on the land. He used Brian Aldiss’s Earthworks (1965), a dystopian novel about ecological ruin, as the basis for his contribution to Seth Siegelaub’s One Month (or March 1969), a 1969 series of artistic actions that were to be carried out by a different artist on each day of the month and were later represented by a textual record of the action that appeared in a calendar-like catalogue.17 Oppenheim’s contribution was Buried Novel 1969 (fig.5), in which the first four pages of Earthworks were to ‘be buried in soil deposits within New York City’, according to the artist’s calendar entry for his assigned day, 25 March. While Oppenheim’s Buried Novel was a reflexive commentary on the structure of One Month, it was also an investigation into the chemical compounds that made up the text on the pages of Aldiss’s Earthworks. The catalogue entry records that 7,350 ‘plaster characters (calcium compound) representing the letters used in constructing these pages will be shoveled under the soil, and left to decompose’. Despite the inaccuracies of Oppenheim’s chemistry (the actual text consisted of carbon black and titanium dioxide printed on fibrous wood pulp), calcium compound (or calcium carbonate) forms the chemical basis of limestone plaster – the very material Oppenheim used in Reverse Processing – and indicates yet another engagement with the various materials that make up the earth. Buried Novel, like many of Oppenheim’s early earthworks, mimicked the cyclical, referential nature of Salt Flat.

Fig.6

Dennis Oppenheim

Branded Mountain 1969

Photograph, cow hide, brands

Private collection

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

Building on the heterotopic interactions that Salt Flat embodied, Oppenheim explored broader relationships between the land and the resources that sprang from it. For example, in Branded Mountain 1969 (fig.6), Oppenheim branded a section of grass in San Pablo, California by burning a 35 ft (10 m) circle with an ‘X’ in it, and subsequently exhibited a branded cowhide alongside documentation of the action. The work can be understood literally, as branding is the process of marking to denote ownership, often of an animal (identified here by the cowhide). However, applying the brand to the land itself relates to the practice of land ownership. This was a historically contentious issue at the site of the work, which was located near the Bay Area, where homesteaders and those who immigrated to California for the gold rush in the mid-nineteenth century had faced a maze of constantly evolving laws that dictated who had rights to own land.18 In addition to questioning institutional control of land ownership, Branded Mountain re-commoditised the land as the installation that documented it entered the art market as a fine art object.

Fig.7

Dennis Oppenheim

Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop 1969

4 photographs, colour, on paper on board

1651 x 4064 mm

Tate T12402

© Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy of the Dennis Oppenheim Estate, New York

In the multi-stage work Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop 1969 (fig.7), Oppenheim moved from figurative transplanting to literal planting, adding yet another layer to the relationship between art, land and commerce. Oppenheim contacted Albert Waalken, a farmer in Finsterwolde, Holland, and proposed that the farmer seed and harvest his land according to the artist’s instructions. Waalken seeded his field with wheat in a line that mimicked the road from the farm to the silo where grain was stored. The wheat was harvested in 1969, in the shape of a large ‘X’ (another recurrent symbol in Oppenheim’s work), and was withheld from processing into grain. As Oppenheim described the project, ‘the esthetic is in the raw material prior to refinement, and since no organization is imposed through refinement, the material’s destiny is bred with its origin’.19 Yet again, Oppenheim was voicing a desire to return the product of the land to its origin, echoing a recurring pastoral ideal within a group of works with a resolutely anti-pastoral aesthetic. He explained his intentions for Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop further as follows: ‘the material [was] planted and cultivated for the sole purpose of withholding it from a product-oriented system’.20 However, this statement was somewhat disingenuous; Oppenheim did indeed exhibit some of the unprocessed grain as a work in Prospect ’69, held at the Kunsthalle Dusseldorf in 1969, thus withholding the product from the agricultural system but placing it in the art market. While Salt Flat used the land to form a self-referential circle that included a site, a material and the creation of an artwork out of their interaction, Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop explored the land as an evolving and open system. The latter was an especially important exception for Oppenheim because he presented the actual physical components of the land (the unprocessed grain) as a work of art, whereas he most often highlighted the conceptual relationship between the land, an action upon it, and its documentation.

Salt Flat was one of Oppenheim’s earliest earthworks to embody a multilayered relationship between a conceptual idea and the process of carrying out a related action on the land. In other works these connections manifested as sociopolitical commentary (as with Branded Mountain), institutional critique (as seen in the Gallery Transplant series) or an investigation of the sites that constituted the lived environment (highlighted by Directed Seeding – Cancelled Crop). In Salt Flat Oppenheim investigated the systemic institutions that shaped society during the 1960s. This critique was borne out of phenomenological explorations of site and refined by interventions into the environment that framed the land as a heterotopia. By investigating the marginalised spaces of the urban landscape, and by concentrating on the physical substances that formulated the earth as a conceptual reformulation of the structures it supported, Salt Flat exposed institutional norms in a cerebral, yet intimately physical, manner.