Fig.1

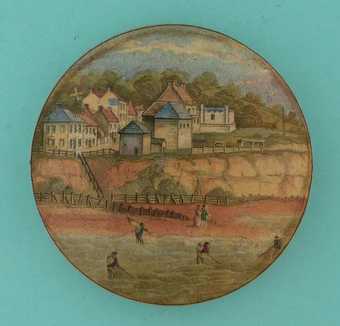

Ceramic pot lid featuring Pegwell Bay and Four Shrimpers c.1860

Today, Pegwell Bay is a suburb on the edge of the town of Ramsgate, in the Isle of Thanet. In Dyce’s time it was a small rural village, a popular destination for excursions from Ramsgate. The boom period for the resort was from 1847 to 1875, meaning that Dyce’s painting Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60 (Tate N01407) was done at the peak of its popularity.1 The village of Pegwell Bay was well known for its abundant shrimps, which could be consumed fresh in the Belle Vue Tavern and its garden at the top of the cliffs. The shrimps were also converted into shrimp paste or shrimp sauce in the nearby factory, and sold in porcelain pots with attractively painted lids. At least twelve different designs are known, all of them showing Pegwell Bay from the west – that is, looking towards the village and the tavern, not towards the cliffs. In one of these, Pegwell Bay with Four Shrimpers c.1860 (fig.1), the combination of figures with shrimping nets and a well-dressed lady and gentleman looking on is comparable to Dyce’s painting. The wooden structure, perhaps the remains of an earlier pier, is also present in both pot-lid and painting.

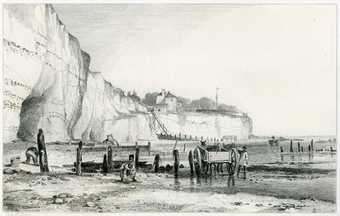

Fig.2

Charles G. Lewis and Edward William Cooke

Pegwell Bay 1830

The existence of the pot-lids explains why reviewers wrote of Pegwell Bay as a place that was familiar – but Dyce’s view of the location was not the usual one. Other images, like the pot-lids, take the view from the west, usually from the top of the cliffs that are shown in Dyce’s painting. An etching by Charles G. Lewis and Edward William Cooke, dating from 1830 (fig.2), shows a view taken from the beach, looking up towards the tavern, including some of the cliff caves that are visible in Dyce’s painting, as well as steps leading down to the beach. Fishermen are hard at work gathering shellfish and loading them onto carts, but there are no holidaymakers to be seen. A painting by Arthur Boyd Houghton, At the Seaside, Pegwell Bay, near Ramsgate, Kent 1862 (fig.3) focuses on the other side of the work/holiday theme. It appears to show a grassy meadow above the cliffs, where children ride on donkeys and locals are trying to get on with haymaking.

Fig.3

Arthur Boyd Houghton

At the Seaside, Pegwell Bay, near Ramsgate, Kent 1862

Maidstone Museum and Bentlif Art Gallery, Maidstone

Pegwell Bay was also well known as a result of Charles Dickens’s short story ‘The Tuggses at Ramsgate’, which was first published in 1836. His comic characters – the family of Joseph Tuggs, a grocer who has suddenly come into money – ride donkeys at Pegwell, lunch on shrimps in the tavern, and then, Dickens tells us, they ‘went down the steep wooden steps … which led to the bottom of the cliff, and looked at the crabs, and the seaweed, and the eels, till it was more than fully time to go back to Ramsgate again’.2 Dickens lived at nearby Broadstairs, so he would have known the area well. There are, however, no signs of crabs or eels in Dyce’s painting: Dickens may have specified these creatures as a parallel to the grasping or slippery aspects of his characters, rather than as a literal indication of what could be seen at Pegwell Bay.

One of the major associations of Pegwell Bay, then, as with any coastal resort, was with middle-class leisure and the fishing activities which catered to the interests of holidaymakers. By the 1850s, however, coastal resorts were also being seen as places where one might contemplate the complexity and beauty of natural history – especially of the shells and pebbles, and of the marine creatures which lived in the rock pools at the water’s edge. Many of the handbooks used by visitors to the coast were published by the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, of which Dyce was a founder-member, as it was thought that a contemplation of God’s handiwork in the ‘book of nature’ would support the faith in that other book, the Christian Bible. The most influential writer on this theme was William Paley, whose book Natural Theology: or, Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, Collected from the Appearances of Nature was published in 1802. Paley argued that proof of God’s benevolence lies in the fact that even humble creatures experience great pleasure in being alive, and one of his examples is the shrimp:

Walking by the sea side, in a calm evening, upon a sandy shore, and with an ebbing tide, I have frequently remarked the appearance of a dark cloud, or, rather, very thick mist, hanging over the edge of the water … When this cloud came to be examined, it proved to be nothing else than so much space, filled with young shrimps, in the act of bounding into the air from the shallow margin of the water, or from the wet sand. If any motion of a mute animal could express delight, it was this.3

Paley’s shrimp cloud was cited by a number of writers of seaside handbooks. The Journey Book of England, published by Charles Knight in 1842, states that the phenomenon might be observed at Pegwell Bay.4 Mackenzie Walcott’s guide to the coast of Kent, published in 1859 and thus exactly contemporary with Dyce’s painting, also associates Paley’s observations with Pegwell Bay.5 Although there is no shrimp cloud in Dyce’s painting, it does show a ‘calm evening’ and ‘an ebbing tide’, and it is very likely that Dyce would have been familiar with Paley’s work, since it was so widely read.

Fig.4

William Holman Hunt

Our English Coasts (‘Strayed Sheep’) 1852

Tate N05665

Photograph © Tate

The coast was also an important defensive boundary against the traditional enemy: France. The 1850s was a time of repeated periods of anxiety about the activities of Louis Napoleon, the nephew of the great Napoleon who had once planned to invade England. Louis Napoleon consolidated his power in France through a coup d’état in 1851 and declared himself Emperor Napoleon III in 1852. It was at this time that Dyce’s friend, the artist William Holman Hunt, painted Our English Coasts, 1852 (‘Strayed Sheep’) 1852 (Tate N05665; fig.4), a view of Fairlight, near Hastings, which deliberately draws attention to the unprotected state of the coastal defences.6 The threat from France receded in the mid-1850s when Britain and France became allies in the Crimean War (1853–6), but the anxieties resumed in 1859, when Napoleon III invaded Italy in the name of Italian unification. At this time several artists joined the Artists’ Rifles, a reserve unit of the British army, to be ready to defend the country if the need should arise. Ford Madox Brown’s coastal landscape Walton-on-the-Naze 1860 (fig.5), which was exhibited, like Pegwell Bay, in 1860, refers to this threat in its inclusion of a martello tower with a Union Jack and a warship anchored in the bay. Walton-on-the-Naze and Hastings were both places with sandy beaches, geographically located within striking distance from the French coast and therefore vulnerable to invasion by sea. So, too, was Pegwell Bay. On a clear day it is possible to see France from Pegwell Bay if one looks to the south-east, and that is the direction in which two of the figures in Dyce’s painting – his son and his wife – are gazing.

Fig.5

Ford Madox Brown

Walton-on-the-Naze 1859–60

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham

A tourist handbook to Ramsgate and the surrounding area, published in 1859, stresses the significance of the Isle of Thanet in British history, as it was here that the Saxons defeated earlier invaders, the Vikings:

here it was our Saxon forefathers bravely battled against the powerful hordes of barbarous Danes, disputing with their best blood every inch of ground which is now trod by a free and happy people. With what pride may an Englishman stand on the white cliffs of Thanet and cry aloud ‘this is the birth place of British Freedom’.7

The same handbook goes on to praise the sea views from Ramsgate:

One of the latter in fine weather embraces a portion of the French coast, between Calais and Boulogne. To some minds this particular view from the West Cliff [the side of Ramsgate closest to Pegwell Bay], will engender feelings of no ordinary nature, especially at the present eventful period, when so many conflicting opinions are entertained, as regards the foreign policy of the French government … Here may the stranger stand, and from his own native shore, behold the very land whose mighty monarch was for so many years the terror of the world – here may he see the country which gave birth to the overwhelming armies of Napoleon I. The land to which the political eye of Europe is at present turned in so much anxiety and doubt.8

This handbook was published too late for Dyce to have used it on his holidays in Ramsgate, but it gives a flavour of the anxieties and associations which could be called up by simple coastal scenes in this strategic location. In October 1858 war was brewing, but had not yet broken out; in 1859 Napoleon III’s armies won major victories over the Austrian Empire at Magenta and Solferino, and the invasion scare was at its height; by 1860, when Pegwell Bay was exhibited, the crisis was over.

The coast around Pegwell Bay was additionally vulnerable to invasion because of its hollow caves, which are evident in Dyce’s painting. Many of these natural caves had been extended by smugglers, some of them leading far inland. The prevalence of smuggling led to a coastguard station being established on the cliffs, with an armoury and coastguard cottages, built in the 1840s. These buildings are still there today, and the armoury may be the one that appears in both Dyce’s watercolour and the oil, about halfway along at the top of the cliffs. Beneath this building, steps were constructed so that the coastguards could have easy access to the foreshore. It is not clear when the steps were built, but if they were there in 1858 they would have been in the place in Dyce’s painting where the line of the cliffs recedes to make a natural alcove, and Dyce has employed artistic licence in omitting them.

As Dyce depicts it, the human economy of Pegwell Bay was delicately balanced in 1858, with holidaymakers and workers mutually supporting one another: the local inhabitants were ensured a good income from the famous shrimps (and if that was not enough, there were always the profits to be made from smuggling, which continued despite the presence of the coastguards). Although there were facilities for the tourists, such as the tavern and its garden, the steps down to the beach and the donkeys, it could still seem a contemplative, elemental place if one went down to the shore and turned away from the village towards the south and west, as Dyce and his family are doing in Pegwell Bay. However, all that was to change very soon after the time of Dyce’s painting. In 1866 James Tatnell opened a licensed bar with a garden by the sea and a landing stage and pier: the new development, the Clifton Tavern, was advertised in the New Ramsgate Guide for 1867 as ‘the most CHARMING MARINE RESORT round the coast of Kent’.9

In the 1870s there were even more ambitious plans to develop Pegwell Bay as a resort, which changed Dyce’s beach and cliffs irrevocably. Six acres of foreshore were reclaimed from the sea and embanked, and the Ravenscliff Gardens and Pier were established in 1879, beneath what had by now become the Clifton Hotel. The developers planned indoor pools and an aquarium which were never built, but a large open-air pool, a skating rink, a restaurant and a photographer’s studio were all completed.10 The cove disappeared, many of the smugglers’ tunnels were blocked up, and a sea wall cut off the shore from the resort, with only a flight of steps leading down to the sea. The development was over-ambitious and the owners became bankrupt almost immediately; later, a convalescent home for seamen was built, but this too fell into disrepair. As a result of all these changes, it is difficult to imagine Pegwell Bay as it was in 1858. The gardens are overgrown and inaccessible, and it is no longer possible to get to the shore from the hotel (which, in 2015, was in the process of being refurbished). At some point, the shrimps must have declined, perhaps as a result of overfishing, and this may have contributed to the failure of development schemes.

Fig.6

Pegwell Bay postcard c.1910

Courtesy of T. Wheeler, Ramsgate Historical Society

The earliest surviving photograph of the view westward – that is, towards the cliffs – dates from around 1910 and shows the view across the Ravenscliff Gardens (fig.6). It is evident from this photograph that the rate of erosion has been quite slow since 1910, especially where the cliffs are protected from the sea by the gardens. The profile of the left-hand edge of the cliffs is different to Dyce’s painting, and it may be here that a significant chunk of cliff had disappeared into the sea. Further along to the right in the 1910 photograph, the coastguard steps are clearly visible, leading down to the gardens. The fence, the steps down into the sea, the trees and the two garden pavilions were no longer there in 2015, but in all other respects Pegwell Bay has, rather surprisingly, changed less in the century since this photograph was taken than it did in the half-century of rapid development after the painting of Dyce’s picture.