An influential modern reading of William Dyce’s Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60 (Tate N01407) is that it is fundamentally about time, and that it represents the threat posed to traditional Christian belief by the vastness of interstellar space and the long aeons of geological time. The art historian Marcia Pointon, in a brief but persuasive article published in 1978, pointed out that Dyce’s title referred to the day when Donati’s comet was at its brightest, and notes that astronomy is here accompanied by geology, the two sciences described by the poet Alfred Tennyson as ‘Terrible Muses’:

It is, surely, no coincidence that Astronomy, represented by the comet, is accompanied in Dyce’s painting by her sister Muse, Geology, apparent in the crystalline clarity of the chalk cliff and the shell-strewn beach.1

In the mid-nineteenth century, new discoveries, especially in geology, were revealing the great age of the earth and the existence of dinosaurs, challenging the traditional Christian belief that the world had been created in six days in 4004 BC. Many Christians, including Tennyson and the art critic John Ruskin, were troubled by the new sciences. Pointon implies that Dyce was too:

The artist’s relatives are seen in microscopic detail, strung out like pebbles in a stony land where all activity is desultory and meaningless whether that of the donkey-keeper, the artist or the boy looking for shells or fossils. Humanity is threatened on either side by the ‘Terrible Muses’ of which it seems unaware … The ‘Terrible Muses’ deny the validity of a single human life and, even more, of a single day.2

The meaning of the painting, Pointon claims, is similar to that of Matthew Arnold’s famous poem, ‘Dover Beach’:

Dyce’s coherent and sensitive appraisal of human perplexity before the beauty and the threat of time made discernible in nature is equalled in our period only, perhaps, by Matthew Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach’ with its ‘grating roar of pebbles’ and its ‘eternal note of sadness’ at the loss of religious faith and disillusionment with human progress.3

Pointon does not mention Charles Darwin in her article. More recent scholars have drawn attention to the publication of Darwin’s treatise setting out his theory of evolution, On the Origin of Species, in 1859 – the very year in which Dyce, most probably, painted Pegwell Bay. According to this reading, Pegwell Bay is a melancholy, bleak, even gloomy painting, expressive of unease, disappointment and a loss of faith in the possibility of finding divinity in nature.4

Fig.1

William Dyce

A Scene in Arran 1858–9

Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums, Aberdeen

However, Tennyson’s reference to the ‘Terrible Muses’ comes in a poem published much later than the painting, the ‘Parnassus’ of 1889. ‘Dover Beach’, too, is later, with a publication date of 1867. None of the exhibition reviewers of 1860 found Pegwell Bay bleak or melancholy, and none of them mentioned fossils. There is no evidence that Dyce himself suffered any loss of faith at any time in his life, whether because of scientific discoveries or for any other reason. Even if he had done so, would he really have chosen to depict a family beach holiday, with portraits of his wife, child and sisters-in-law, as the setting for an expression of religious doubt? The painting was sold to his father-in-law, James Brand. Brand bought at least nine paintings from Dyce: four of them were of religious subjects. One of the other three landscapes bought by Brand, A Scene in Arran (fig.1), was a comparable picture to Pegwell Bay, since it was produced as the result of a family holiday.5 A Scene in Arran was actually commissioned by Brand, and it has been suggested that the four children in this painting were portraits of Dyce’s children.6

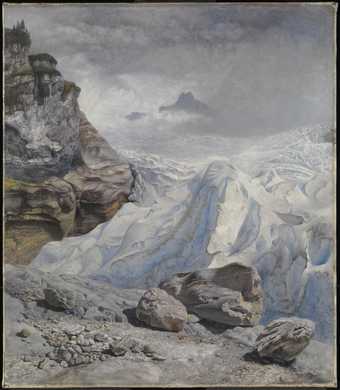

Fig.2

John Brett

The Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856

Tate N05643

Photo © Tate

Many artists were interested in geology and astronomy in the 1850s and 1860s, although it was unusual for a painting to combine them. Two geological paintings which have a close relationship with Dyce’s painting are John Brett’s The Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856 (Tate N05643; fig.2) and Charles Napier Hemy’s Among the Shingle at Clovelly 1864 (fig.3). Both artists had strong religious beliefs at the time they painted their pictures. John Brett was later to lose his faith, but in 1856 he was a devout Christian who wrote in his diary of his fellow artist John William Inchbold: ‘his whole nature is exquisitely tuned Christ living in him very manifestly’.7 Dyce could have seen The Glacier of Rosenlaui at the 1857 exhibition at the Royal Academy, London. Charles Napier Hemy was a Roman Catholic who had spent time as a Dominican monk in the early 1860s, and when he died he chose to be buried in his Dominican robes.8 The pebble-strewn beach in his painting of Clovelly was very probably inspired by Dyce’s Pegwell Bay, but Hemy took the minute elaboration of the pebbles even further, lovingly exploring the contrasts in form and the shaping effects of light and colour. The fourth volume of Ruskin’s Modern Painters, subtitled ‘Of Mountain Beauty’ and published in 1856, has many passages extolling the beauty of rocks and attributing their distribution to Divine Providence, which encouraged devout artists like these two to take up the study of geology.

Fig.3

Charles Napier Hemy

Among the Shingle at Clovelly 1864

Laing Art Gallery (Tyne and Wear Museums), Newcastle

Equally, astronomy could be seen in this period as supporting rather than undermining Christian belief. One artist who was particularly interested in the night sky was Samuel Palmer, and he painted a watercolour of a landscape with Donati’s comet in the sky, which was exhibited at the Society of Painters in Watercolour in 1859, where Dyce might well have seen it. Entitled The Comet of 1858, as Seen from the Heights of Dartmoor 1858–9 (fig.4), it includes a group of figures, with a woman holding her baby up and pointing towards the comet – a possible source for the figure of the artist gazing at the comet in Pegwell Bay. Palmer was a devout artist, who maintained a strong Christian faith throughout his life. Art historian William Vaughan has suggested that Palmer may have been influenced by the sermons on astronomy published in 1817 by Thomas Chalmers, the well-known Scottish churchman. Chalmers argued that the study of astronomy should strengthen our belief in God by raising the mind above earthly things:

there is much in the scenery of a nocturnal sky, to lift the soul to pious contemplation. That moon, and these stars, what are they? They are detached from the world, and they lift us above it. We feel withdrawn from the earth, and rise in lofty abstraction from this little theatre of human passions and human anxieties. The mind abandons itself to reverie, and is transferred in the ecstasy of its thoughts, to distant and unexplored regions. It sees nature in the simplicity of her great elements, and it sees the God of nature invested with the high attributes of wisdom and majesty.9

Fig.4

Samuel Palmer

The Comet of 1858, as Seen from the Heights of Dartmoor 1858–9

Private collection

Dyce would have known Chalmers when he was living in Edinburgh in the early 1830s. Both were Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Dyce being elected in 1832 and Chalmers in 1834. The attitude of the artist pausing to look up at the comet in Pegwell Bay is not incompatible with Chalmers’s sense of wonder at the ‘majesty’ of the ‘God of nature’.

To those who felt secure in their faith, the vastness of space was an indication not of the meaningless of human life, but of the immense power and majesty of God. In a sermon published anonymously in 1858, the trajectory of Donati’s comet prompted a meditation on the brevity of life on earth and the Christian promise of the immortality of the soul:

We, like the comet, are here but for a short time. We live upon our earth, only to pass onward to another scene; but when once we have passed onward, we never more return, nor die a second time … We know where we shall be in the long unending future which we shall have entered ere this wandering star returns.10

There is no evidence that Dyce knew this particular sermon, but it is almost certain that he would have read another, similar text on the comet. This was a letter to the Times, which was republished in 1858 in the English Churchman, a newspaper that Dyce is known to have read. The author, Vivian Webber, emphasises the compatibility of astronomy with religion:

Surely the contemplation of such a magnificent subject as astronomy tends to spiritualise and elevate us … even the vast spaces we have been considering are as nothing in the eyes of Him to whom ‘a thousand years are but as yesterday’. What glorious scenes lie beyond this immensity: there is to be found the very abode where God has chosen to display Himself in the most magnificent manner! … As magnificent truths are to be gleaned from the starry firmament as from the earth below.11

Seen in this light, the comet was a sight to arouse wonder and devotion. According to the art historian Roberta Olson and the astronomer Jay Pasachoff, Donati’s comet was ‘absolutely captivating’, and one of the most beautiful ever recorded.12 It was first spotted by Giovanni Battista Donati, using a telescope, on 2 June 1858. By 19 August it was visible to the naked eye, and remained so until 4 December. Its fame derives in large part from its wonderfully broad, sweeping tail, as well as from two less frequently seen thinner tails.13 The comet was at its brightest on 5 October 1858, when it passed in front of the bright star Arcturus. On this evening it appeared at sunset, about 5.30 pm, and remained visible until it set, the head at about 9 pm, the tail hours later. William Turner of Oxford exhibited a watercolour and gouache work, entitled Donati’s Comet, Oxford, 7:30 p.m., 5 Oct. 1858 1858–9 (fig.5), at the Society of Painters in Water-Colours in 1859. It may well have been this watercolour that gave Dyce the idea for Pegwell Bay, or if the painting was already under way, it may have suggested his title, with its specific reference to location and date.

Fig.5

William Turner of Oxford

Donati’s Comet, Oxford, 7:30pm, 5 Oct. 1858 1858–9

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

The comet appears much larger and brighter in Turner’s painting than it does in Dyce’s painting. Similarly, Samuel Palmer’s watercolour, also shown in the 1859 exhibition, depicts a larger and brighter comet. Indeed, Roberta Olson and Jay Pasachoff have suggested that Dyce deliberately made the comet look smaller than it actually appeared in nature: his depiction is smaller than other representations of it from the time.14 According to a report in the Illustrated London News, the tail of the comet was upwards of 32 degrees in length, longer than the 25 degrees of the Great Comet of 1811, so that ‘we have seen during the past few months a comet the largest, if not the brightest, visible within the memory of man’.15 On the other hand, Dyce does seem to be accurate in his placement of the comet in the western part of the sky: the same report says that ‘the tail of the comet was very bright and large from Oct. 3 to Oct. 11, and presented a magnificent aspect in the western heavens during this interval’. The watercolours by Turner and Palmer represent the comet as an exciting, dazzling spectacle. By contrast, Dyce’s reference to the comet is extremely subtle, and one wonders whether the critics would have noticed it at all if it had not been clearly signalled in his title.

When Dyce died in February 1864, published obituaries stressed his devotion to the Anglican Church. The Morning Post declared that ‘he used his great powers for religious purposes, and the Church owes him a large debt of gratitude for his persistent devotion of his talents to her service’.16 The Illustrated London News was more specific on this point:

He was, as far as we are aware, the only painter, with the exception of Mr. Herbert, familiar with the writings of ‘the Fathers’. In answer to Mr. Ruskin’s crude paradoxes on Church polity in the pamphlet entitled ‘The Construction of Sheepfolds’, he wrote the able and vigorous ‘Shepherds and Sheep’.17

Indeed, Dyce devoted a substantial proportion of his time to church matters. He founded the Mottet Society and wrote four articles on church music in 1841; in 1844 he published an edition of the Book of Common Prayer with its ancient Canto Fermo (plainchant). He wrote numerous articles and letters to newspapers about matters of church ritual and Christian observance. He was friendly with many of the major figures in the nineteenth-century church, especially those on the High Anglican/Roman Catholic wing, including John Henry Newman, Nicholas Wiseman, Edward Bouverie Pusey and John Keble. An indication of Dyce’s state of mind at the end of 1859, and presumably after he had painted Pegwell Bay, is seen in a long letter published in the English Churchman on 15 December 1859. Here Dyce argued that true obedience to the law of the Sabbath ‘does not stand in the observance of days or weeks or years, but in the perpetual rest into which those who believe have entered (Heb.IV.3) and which is kept not by abstaining from servile works, but by ceasing from sin’.18 It is likely that he was at least as troubled by conflicts within the church as by the conflict brewing between science and religion.

There may be other allusions in Pegwell Bay than the ones that now occur to twenty-first century observers. Art historian Malcolm Warner has pointed out that St Augustine landed near Pegwell Bay on his mission to convert the English to Christianity in 497 AD. Dyce would have known this event well, since he had painted a mural of Augustine baptising King Ethelbert of Kent.19 The comet, therefore, may be an echo of the star of Bethlehem, which led the three Magi to Christ. The boy standing on the edge of the shore, and looking out to sea, apparently lost in thought, might have been suggested to Dyce by the story of Sir Isaac Newton’s description of himself as being ‘like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me’. This anecdote was included in Sir David Brewster’s biography of Newton, which had recently been republished.20 Brewster was a prominent figure in scientific circles in Edinburgh, and Dyce, who had many family connections with scientists, would have known him.21 The anecdote was so well known that Dante Gabriel Rossetti had been asked in 1855 to illustrate it for a mural in the new University Museum of Natural History in Oxford.22

Fig.6

William Dyce

George Herbert at Bemerton c.1860

Guildhall Art Gallery, Corporation of London

Pegwell Bay was accompanied by two pictures of traditional Christian subjects at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1860. In the following year, 1861, Dyce exhibited a painting entitled George Herbert at Bemerton of c.1860 (fig.6). This time he made the meaning of the painting clear by inserting the first verse of a poem by Herbert in the Royal Academy catalogue, next to the title of his painting:

Sweet day, so cool, so calm, so bright!

The bridal of the earth and sky –

The dew shall weep thy fall tonight:

For thou must die.23

This poem has four verses: the middle two lament that the rose and the spring, too, must die. Yet the poem ends on a positive note by affirming belief in the immortality of the soul:

Only a sweet and virtuous soul,

Like season’d timber, never gives;

But though the whole world turn to coal,

Then chiefly lives.

The painting was a popular and critical success. One reviewer suggested that there was a direct connection between Dyce’s minute finishing and his devotional subject:

The elevation of the subject, the pure religious sentiment embodied, would seem to demand nothing less than the most absolute truth in the minutest particular. In such a picture the tricks and shams of convention would be out of place, quite at variance with the pure holy feeling with which the work is inspired.24

Seen in this light, the hyperreal clarity and detail in Pegwell Bay might also be seen as visionary, an effect of heightened awareness brought on by the beauty of the natural world, enhanced by religious faith.

Fig.7

Gentile da Fabriano

The Adoration of the Magi 1423

Uffizi Gallery, Florence

The question remains as to whether we go can further and say that Pegwell Bay is a religious painting. Dyce would have known that Italian Renaissance artists represented the star of Bethlehem as a comet, and he would also have known paintings in which one or more figures observe a miraculous event while other figures in the painting remain oblivious to it.25 A specific compositional source could be Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi 1423, now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence (fig.7). In this painting, the three Magi are shown in the background, observing the star/comet in the sky, just as Dyce himself observes Donati’s comet in his painting. They are shown again in the foreground. Dyce’s three women, with their contrasting positions from standing to kneeling and their bulky clothing, echo the placement of Gentile’s three Magi. Caves occur both in paintings of Christ’s nativity and in depictions of his entombment; the three Magi who came soon after his birth are echoed in the three Marys who attended his tomb. Even the donkeys could be seen to refer to the life of Christ and his entry into Jerusalem. The combination of the comet in the sky and the caves in the cliffs may therefore be a reference not to the late nineteenth-century concept of the ‘Terrible Muses’ of astronomy and geology, but to the much older tradition of Christian iconography, produced by an artist who had a thorough knowledge of both Renaissance painting and the Bible.

If Pegwell Bay is indeed a disguised religious painting, this would bring it closer to other Pre-Raphaelite modern life scenes, such as John Everett Millais’s The Blind Girl 1856 (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham) and John Brett’s Stonebreaker 1857–8 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool), in which Christian symbols appear as natural elements in the landscape.26 It might be seen as a meditation on birth, death and resurrection, in an appropriate setting since the seashore was often regarded as the metaphorical boundary between life and death. In the background, Dyce looks up at the comet, fixing his eye on heavenly things. In the foreground, his wife and child look anxiously towards a future without him, but the presence of the two sisters is a reassurance that the wider family will support them. Whether the painting is about faith or doubt (and it could be argued that one implies the other), it is clearly much more than a literal transcript of an October day on the coast. Neither the comet nor the chalk cliffs appear to have been accurately transcribed, and perhaps this was even deliberate on Dyce’s part. Despite the ‘scientific’ appearance of the painting, Dyce’s writings in the 1850s are much more concerned with religion than with science, as he made clear in an unfinished letter found among his papers, dating to 1857:

What people in this country have to learn is that the science of the Fine Arts is not Physical Science, but the science of the Beautiful; and that it belongs to the region of Ethics not of Physics.27