Mousehold Heath, Norwich c.1818–20 (Tate N00689; fig.1) depicts a wide expanse of relatively featureless countryside, shown sometime towards evening on a summer’s day. While heathland plants in the left foreground of the composition are shown in some detail, the rest of the picture offers a more generalised approach to representing the landscape. At the right Crome has introduced two rustic figures, one of whom points towards the horizon, and there are sheep and cattle in the distance and the occasional figure, all painted in an abbreviated style using minute touches of paint. These provide some idea of the kind of landscape this is – a terrain useful for pasturing animals – but above all they give a sense of scale as the eye traverses the depicted scene from foreground to background. Over half of the composition is given over to the sky and the broad masses of cloud welling up behind the horizon. Aside from the large tract of heathland identified in its title, therefore, the painting seems to be a scene without a subject: there is no obvious focus of attention, no narrative devices or genre-like depictions of rural life, no conventional signs of the beautiful or the picturesque. What Crome offers instead is an exploration of space, with the landscape unfolding into the far distance under an enormous sky.

Fig.1 John Crome

Mousehold Heath, Norwich c.1818–20

Oil paint on canvas

1099 x 1810 mm

Tate N00689

Photo © Tate

The location for the scene is Mousehold Heath, an area of heathland above the city of Norwich. Crome painted numerous pictures of this kind of landscape but Mousehold Heath is by far the most ambitious. It was acquired for the National Gallery in 1863 and has long been considered to be one of Crome’s most important paintings.1 However, many details about the picture remain elusive. Crome’s motives for producing the painting are unknown, nor do we know what title he would have given to it or whether it was exhibited in his lifetime. The painting’s date has also been the topic of much scholarly discussion, the general consensus being that it was painted towards the end of Crome’s career, with dates suggested for its production within a span of 1814–20. The painting has stylistic affinities with Crome’s later work and in Tate’s and the authors’ opinions a date towards the end of this range, around 1818–20, is not unreasonable. However, it is unlikely that a compelling argument that commands universal agreement will ever be made regarding the date of the painting’s execution.2 Indeed, the debates surrounding Crome’s works have often been heated, especially as regards attribution and the connoisseurial expertise required to identify his oeuvre and place it in order.3

Although Mousehold Heath dates from towards the end of Crome’s life when his mature style was fully in evidence, his artistic training at an earlier period provides important evidence of his approach to painting and the technical standards he maintained throughout his career. Crome began his life as an artist in 1783, apprenticed to the Norwich coach, house and sign painter Francis Whisler. His humble background led to romanticised accounts of his early penury, sharing a garret with the artist Robert Ladbrooke and painting with what materials he could afford. His friend, patron and early biographer Dawson Turner tells of Crome using ‘cast-off aprons … for canvases’ and of being ‘reduced to clipping the hair from the tail of his landlord’s cat’ to make brushes.4 The apprenticeship would have offered valuable experience at a time when there was little formal tuition available to artists in traditional and durable painting techniques. Lecturing to the students of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1807, John Opie, Professor of Painting, declared:

It would be as tedious as useless to enter here into a detail of the various materials used in painting, and the different modes of applying them, the proper knowledge of which it is the province of experiment and practice alone to teach.5

Painters learned their craft from fellow artists and from the study of old master paintings. As a drawing master to the local Norfolk gentry, Crome was well placed to study and take inspiration from the much-admired Dutch seventeenth-century landscapes in their collections. His friend and patron, the amateur painter Thomas Harvey, owned such a collection at his manor house in Catton, just outside Norwich, and it was through Harvey that Crome became friends with the Royal Academicians John Opie and William Beechey.6 Writing in 1798, Amelia Opie described her husband and Crome together in Harvey’s ‘painting-room’ and her husband ‘painting for Crome: that is, the latter looking on, while the former painted a landscape or figures’.7 Beechey, who had also begun his illustrious career as a coach and housepainter, later recalled how Crome, when in his twenties, frequently visited his London studio ‘to get what information I was able to give him upon the subject of that particular branch of Art which he had made his study’.8 Like many painters, Crome owned practical painting manuals, both late seventeenth-century and more contemporary, as well as books on the theoretical principles of painting. His library included popular works of the day, such as Leonardo’s treatise on painting (1651), Claude’s Liber Veritatis (1776–7) and Joshua Reynolds’s Discourses (1769–90).

Canvas and ground

To provide insight into Crome’s choice of materials and his processes in making Mousehold Heath, the painting has been examined and compared with the technical research carried out on other works by Crome in the collections of Tate and the Norwich Castle Museum.9 Mousehold Heath is painted on a medium-weight, plain woven linen canvas. To prime the canvas for painting, it would have been stretched over a simple wooden frame and brushed with a glue-size layer to seal the fibres before the oil ground was applied. The ground is a pale biscuit colour, made from lead white and quantities of coarsely ground chalk tinted with yellow and brown ochre. It was applied in a single layer that conforms to the weave texture.10 Similarly thin grounds that showed the texture of the weave had become increasingly popular in the late eighteenth century.11 The surface is lightly textured by very fine horizontal grooves left by the stiff brush used to apply the priming.

It appears that Crome bought this canvas ready-primed, as the trace of an excise stamp is visible at one edge. At this time excise duties were payable only on pre-prepared, primed or painted canvases.12 Commercially primed canvases were sold ready-stretched, in standard sizes based on (and named after) portrait types, to be turned on their side for use by landscape painters.13 Mousehold Heath falls between two standard sizes: a ‘Bishop’s half-length’ and a ‘full length’, and the deformations in the weave known as ‘cusping’14 are only apparent along the left and top edges, suggesting it was either cut down from the larger size or bought from the end of a roll of ready-primed cloth then attached to a wooden stretcher by Crome himself.

In this respect, the painting is unusual in relation to Crome’s oeuvre. Like many of his Norwich contemporaries, Crome generally primed his own supports.15 Research into a body of Crome’s works has shown how he frequently manipulated and emphasised the physical quality of his earlier canvases for his final effect by applying primings in ways that exploited the textures of the raw canvas.16 Examination of Slate Quarries c.1802–5 (Tate N01037; fig.2) shows that Crome primed a very coarse and open-weave canvas with an exceptionally thin, red ground to expose the uneven and fibrous texture of the sacking-cloth weave.

Fig.2

John Crome

Slate Quarries c.1802–5

Oil paint on canvas

Tate N01037

Photography © Tate

This contributed to a final rough, textured surface effect. This aesthetic was shared by other landscape artists such as John Sell Cotman and J.M.W. Turner, the latter of whom, at times, used exceptionally open weave canvases with thin grounds.17 There are also instances of Crome applying his ground selectively to expose some canvas in his final design, for example in Yarmouth Jetty c.1810–14 (Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich).18 In Moonrise on the Yare (?) c.1811–16 (Tate N02645; fig.3) Crome primed a fine-weave canvas with a thin translucent brown toning layer, allowing the colour and texture of the weave to shine through. He enhanced this effect further by scraping back the thin paint to reveal the tops of the canvas weave, as is seen in the mast and sails of the windmill. For Mousehold Heath and others of Crome’s late works, it is more through expressive brushwork and manipulation of paint that he achieves his intended final effects, and the brushed texture of the ground must have provided tooth, aiding the movement of his brush and paint application.

Fig.3

John Crome

Moonrise on the Yare (?) c.1811–16

Oil paint on canvas

Tate N02645

Photography © Tate

Underdrawing

No underdrawing in graphite pencil, ink or charcoal, all of which would be discernible in an infrared (IR) image, has been detected on Mousehold Heath, although Crome could have used chalk or pipeclay to outline the main forms on the biscuit-coloured ground, marks which would not be visible in IR. There are few surviving preparatory sketches for Crome’s paintings, and none relating to Mousehold Heath.19 Crome is known to have taken his pupils out to sketch and paint studies directly from nature; surviving pencil and oil studies of plants and flowers provided useful reference material when in the studio (see figs.4 and 5). He may also have worked directly from plant cuttings.

Fig.4

John Crome

Plant study: A Burdock undated

Pencil on white card

140 x 190 mm

The Courtauld Gallery, London

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Fig.5

John Crome (attributed to)

Study of Foliage undated

Oil on cardboard

248mm x 324 mm

Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich

© Norfolk Museums Service

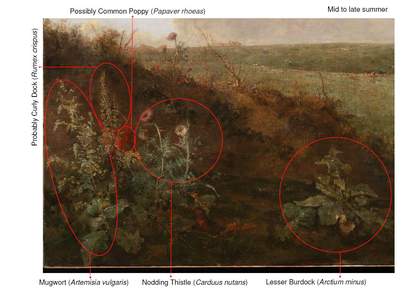

If the group of heathland plants in the left foreground of Mousehold Heath was transposed from a detailed oil sketch, this may explain the angle and level of illumination given to it, which appears slightly at odds with the rest of the landscape. The accuracy of Crome’s rendition has allowed these plant species to be identified as common poppy, mugwort, nodding thistle, lesser burdock and curly dock (fig.6).20

Fig.6

Plant species identified in the left foreground of Mousehold Heath

Photography © Tate

Painting sequence

Crome followed the prevailing method of building up a painting, starting with the ‘lay-in’ or ‘dead colouring’, followed by the working up and then the ‘finishing’ stage. This was the convention for both portraitists and landscapists, reaching back to the naturalistic Flemish and Dutch painters of the seventeenth century,21 and was frequently described in manuals on painting.22

Crome first laid in the shapes of the landscape and principal figures with a thin, brushy, semi-translucent brown underpainting. As in many Dutch seventeenth-century landscapes, this underpaint also plays a role in the final image, forming warm brown mid-tones or the base for glazed shadows in the foreground, mimicking the effect of earth beneath or behind vegetation (see the detail of burdock leaves in the left foreground, fig.7). Much of the sky is underpainted in a thin deep purplish blue which also serves for the dark tones of the clouds. Crome also made use of the pale ground in the final image; it forms the base of the distant cultivated field on the far right, and is exposed in the sky, forming the lightest point at the centre of the horizon.

Fig.7

Mousehold Heath, detail of burdock leaves

Photography © Tate

Fig.8

Mousehold Heath, detail of the left foreground

Photography © Tate

In a second stage Crome worked up the main structural features of his landscape: the bare bones of the exposed sandy terrain, rocks in the foreground banks and distant paths. He painted most of the foreground plants directly over his first thin brown wash, while the thistles in the left corner were added later over a thick layer of dark pinkish-brown soil. Painting in one or two layers for each element, he worked wet-in-wet, premixing his colours on the palette and often using complex mixtures that contain many translucent or semi-translucent pigments. He left generous margins around the carefully studied plants, interspersing them with more vigorous, broad brushwork, then returning to redefine and merge edges while the paint was still workable. Once it was touch dry, Crome finished his painting with extensive translucent toning glazes to strengthen shadows and add warmth and saturation, further extending his variety of colour and tone. Flecks and spots of thick paint were added in warm pinks and oranges for sunlit highlights (see the detail of the left foreground, fig.8).

Paint techniques and pigments

It is tempting to see a correspondence between Crome’s wide variety of colour and textural paint effects and the myriad shifting surfaces, tonal variations and atmospheric depth in the natural world he depicts. There are certainly comparisons to be made with the brushwork of Hobbema, who was said to have been a key influence.23 Crome’s expressive, broad paint handling ranges from impressionistic bravura to startlingly delicacy, as seen in a close detail of the vegetation on the right bank (fig.9).

Fig.9

Mousehold Heath, detail of the vegetation in the right foreground

Photography © Tate

It is clear from such details that Crome did not seek to disguise his painting process. Brush marks are often discrete rather than blended, and the action of applying paint to canvas is evident, the texture of his marks exposing the shapes and sizes of his brushes. Crome added quantities of a very coarsely ground chalk to the paint to help retain this texture. Chalk appears translucent in oil but serves as a bulking agent, thickening each brushstroke to give body. He created a stiff, sharp impasto in the heads of the patch of thistles, using a small brush laid lengthwise to pull the paint up into peaks (fig.10). A detail of the neighbouring mugwort leaf shows how his brush pushed the paint up into rounded ridges describing the curl of the leaf (fig.11).

A sample taken from bodied paint of a foreground burdock leaf suggests that Crome possibly used the medium megilp to create some impasto effects. At this time megilp often consisted of varying proportions of linseed oil prepared with lead driers and mastic resin.24 Mixed into paint on the palette, it added body for textural effects, but could also be thinned into glazes. Its use often led to drying defects in the paint soon after it was touch dry, either wrinkling or wide contraction cracks. Both of these can be seen across some surfaces of thickly applied paint.

Fig.10

Mousehold Heath, detail of a thistle head

Photography © Tate

Fig.11

Mousehold Heath, detail of a mugwort leaf

Photography © Tate

The wild flower stems silhouetted against the sky are also thickly painted, drawn into sharp focus with a fine pointed brush used to dab paint on in staccato dots, creating an embossed surface effect. Close inspection shows that many of these tiny foreground flowers in the curly dock and mugwort are marbled, with white swirled into blues, pinks or oranges in a single stroke (fig.12). In contrast to this precision, Crome’s rendering of dappled patches of foreground scrubland uses thin and rapid, sketchy brushstrokes of dark greens and browns, modulated by darker patches of glaze, sometimes applied by Crome with the very tips of his fingers rather than a brush (fig.13).

Fig.12

Mousehold Heath, macro detail of curly dock flowers

Photography © Tate

Fig.13

Mousehold Heath, detail showing glaze dabbed on with fingertips

Photography © Tate

For his illusionistic rendering of distant coarse grassland and sandy tracks, Crome created a correspondingly rough surface. Using a scumbling technique, he loaded his brush with bodied, opaque paint, lightly dragging it to form broken brushstrokes that allowed the darker semi-translucent underpaint to show through. The technique was repeated in subtly shifting hues. Crome applied a resinous green glaze and then wiped it from the high points of texture to further enhance the rough choppy character of the distant heath.25 He altered his textural effects and tonality to enhance the atmospheric recession of the landscape; the distant plane is smoother, its textures softer, and the tonal shifts of the deeper grey-blue less focused (fig.14). The influence of Turner on Crome was recorded by Dawson Turner, who wrote of Crome returning from the Royal Academy exhibition in London in 1818 ‘with his whole soul full of the admiration at the effects of light and shade, and brilliant colour, and poetical feeling, and grandeur of composition displayed in Turner’s landscapes’.26 Certainly, a strong iconographic and stylistic comparison has been made between Mousehold Heath and Turner’s Frosty Morning exhibited 1813 (Tate N00492; fig.15), which Crome is likely to have seen and which shows a similar handling of paint in describing rough terrain and atmospheric effects.27

Fig.14

Mousehold Heath, detail of the distant heath

Photography © Tate

Fig.15

J.M.W. Turner

Frosty Morning exhibited 1813

Oil on canvas

Tate N00492

Photography © Tate

Crome’s later paintings tend to be lighter and more colourful than his earlier works, although his range of pigments appears to have remained fairly constant throughout his career and did not differ from those of many of his contemporaries. Paints were supplied ready-made in pigs’ bladders, or Crome could have obtained the dry pigments to grind into oils and resins himself. There were no specialist artists’ colourmen established in Norwich until 1850,28 and so Crome’s materials may have come directly from London or through local family businesses of gilders and carvers, such as the Freemans.29 Unlike Turner, who was notable for his readiness to try new pigments, analysis of Crome’s pigments shows him using a traditional palette, one that would have been largely familiar to artists working a century earlier.30

For Mousehold Heath, Crome relied heavily on a range of earth pigments in lead white to render the colourful display of many reds, pinks and oranges that tint the flowers, grasses and plant stems on the brow of the foreground hills with the rays of the setting sun (fig.16). These natural earth pigments offer a wide range of hues: ochres, siennas and umbers, their variations determined by their differing proportions of clay and iron oxides. The brighter, synthetic earth pigment Mars orange was also used extensively, while the red accents of the poppies were painted with vermilion.

Fig.16

Mousehold Heath, detail of the brow of the hill at the left

Photography © Tate

Before the production of emerald green there were no bright, strongly tinting greens. Crome used semi-translucent green earth (a ferrous silicate) as the basis of his greens, modifying this with several other pigments to achieve a number of subtle shades. He used it very coarsely ground, which makes the colour more intense than does fine grinding. For the warm, light green dock leaves he used a complex combination of coarsely ground green earth mixed with Mars orange, traditional Prussian blue, bone black, Antwerp brown, yellow ochre and the bright opaque patent yellow (lead oxychloride). Prussian blue was an important pigment from the early eighteenth century which gave a darker and more muted tone in mixed greens and a more intense colour than could be achieved with indigo. Crome increased his proportions of Prussian blue for highlights on his burdocks, the cool blue-green foreground thistles and the distant heathland.

Fig.17

Mousehold Heath, detail of the sky

Photography © Tate

For the pale blue sky Crome chose smalt rather than Prussian blue. A blue pigment made from coloured glass, smalt was widely used in the seventeenth century, but less so by Crome’s time, although Turner also used smalt in his skies. Traditional advice given in one of Crome’s painting manuals was to grind coarsely ‘for Smalt or byce utterly lose their colour in grinding’,31 and microscopic examination of the sky has revealed extraordinarily large particles, even larger than the particles of green earth. The painting of the sky in Mousehold Heath is a tour de force. The expanse of pale blue is animated by the impressions left by vigorous, broad brush strokes: stippled circles of a stiff 4 cm brush head lead each rapid zig-zag stroke. The texturing is enhanced by the underlying darker blue shining through the marks made in this thin upper layer, although as oil paint becomes more transparent with age this effect may have been slightly exaggerated (fig.17). The underpaint forms the basis of the clouds, which are modelled by veils of semi-translucent washes in creams, oranges and greenish yellows. Crome varied his technique across the surface; towards the towering clouds at the right he allowed the biscuit-coloured ground to shine through exceptionally thin layers of purplish blue underpaint. However, a harsh cleaning in the past may have exposed more of this priming than he originally intended. Crome edged the clouds with single, straight dabs of thick cream tinted with Mars orange, yellow ochre and the brighter patent yellow pigments.

‘Finish’

One traditional means of achieving visual coherence, whereby parts of the design could be unified into a harmonious vision, was to apply ‘finishing’ glazes. There were artists at this time, inspired and perhaps misled by the aged appearance of old master paintings, who used overall toning glazes in translucent browns to add depth and subdue their colours and brushwork.32 In Mousehold Heath and other works Crome made extensive use of local glazes in varied colours, enhancing his brushwork in innovative ways, rather than veiling all with a single, harmonising tone.

Fig.18

Mousehold Heath, detail of finishing glazes

Photography © Tate

The glaze medium contained a natural resin, the same material as was used in varnishes. It gave a saturating, glossy appearance and was frequently used at this period for toning or glazing as well as varnishing. Drying more quickly than oil alone, the use of resins also allowed the artist to continue painting soon after, with final light opaque scumbles or highlights. Although no detailed analysis of the medium has been carried out on Mousehold Heath, analysis of other works by Crome has found the resins mastic and the cheaper rosin in his glazes, in addition to linseed oil.33 The translucent and semi-translucent pigments used for glazes include Antwerp brown, green earth, bone black, Prussian blue, smalt and a red lake, likely to be carmine. These were coarsely ground to help intensify and perhaps retain their colour, and used in varying proportions to adjust the hues, producing warm pinks and browns and the greens seen in the glazes which enhance the grass of the distant heath. Crome liberally glazed the sandbanks of the right foreground using increased proportions of red lake to lend a warm rosy hue in keeping with the afterglow of the setting sun. Deep, rich red brown glazes intensify shadows between plants and were dotted or wiped onto the surface (fig.18). This use of local glazing is one of the most adventurous of Crome’s painting processes, and may have been inspired by Turner’s example.

Figures and changes

Crome’s placement of figures and animals in the landscape enrich the space, and help to convey the illusion of recession. Following pictorial conventions of aerial perspective he silhouetted the standing pointing figure against a light background and then softened the colours, textures, shadows and contours as they reduce in scale, down to the grey dots on the far horizon (fig.19). While distant animals and figures are painted over the landscape, the principal figures were blocked in at an early stage with the brown underpainting, which is exposed as the mid-tone in the raised arm. In the finishing stage, Crome added two balancing accents of bright vermilion red to form the highlights on the seated man’s jacket and on the poppies, painted over the finished wild flower group. Crome also edged the figures with thick ridges of the same bright orange paint that he used for the sun-drenched plants on the left near the horizon (fig.20).

Fig.19

Mousehold Heath, detail of the centre of the horizon

Photography © Tate

Fig.20

Mousehold Heath, detail showing standing and seated figures

Photography © Tate

Crome blocked in another foreground figure at the underpainting stage.34 A man in a broad-brimmed hat, of similar size to the standing figure and also having a raised, pointing arm, appears to be emerging around the bend of the hill in the central foreground (see figs.21a and 21b, which show an infrared image with the figure visible, alongside a detail of the same area as seen in normal light). One advantage of the very thin underpainting was that it allowed the artist to visualise the overall design before thicker layers were applied, so that early corrections could easily be made. The abandoned figure may be an early version of the standing figure we see on the right, or simply an extra figure that Crome decided not to work up. Crome made a number of other small changes to his composition at a later stage in the painting process. In the same area, just to the left of the underpainted form, we can see a much smaller and therefore more distant figure which was painted on top of the landscape and then partially removed. It is visible in the infrared image as a dark dot and inverted V-shape, and is only just discernible on the surface because Crome blotted out with green paint the remaining dark brown of the head and remnants of a reddish-brown coat. As a result, it is not possible to determine whether the figure is male or female.

Fig.21a

Mousehold Heath, infrared detail showing an underpainted figure

Photography © Tate

Fig.21b

Mousehold Heath, corresponding detail in normal light

Photography © Tate

In addition to these, there is further group of figures that were painted out by Crome. These face square on, emerging at the crest of the hill at the right side, with a woman at their centre, her head lowered and wearing a cap. Fully painted, they are visible in both IR and X-ray images (see figs.22a, 22b and 22c which show the same detail in IR, X-ray and normal light). These figures are barely perceptible on the painting’s surface, but we can make out the cream-coloured sleeve and cap of the woman, the pink of her hands and, to her left, a man in a broad-brimmed hat.

Fig.22a

Mousehold Heath, infrared detail showing a group of figures

Photography © Tate

Fig.22b

Mousehold Heath, corresponding X-ray detail

Photography © Tate

Fig.22c

Mousehold Heath, corresponding detail in normal light

Photography © Tate

History of the painting

At an early point in its history the painting was cut into two pieces,35 which were subsequently rejoined when the canvas was lined, a process which involved the attachment of a second canvas to the back of the original, in this case using a glue-paste adhesive. The divide is left of centre, forming an almost perfect square on the right (see fig.23, which shows the painting in raking light, revealing its division). One account, likely fictional, tells of how the painting came into the possession of the painter Joseph Stannard, who used the two pieces as window blinds. Another story claims that it was sold to a dealer in Windsor, Mr French, who employed Edmund Bristow, an animal painter, to paint in animals and figures, to add interest to the composition. Goldberg states that the canvases were rejoined, the painting was lined and restored, and ‘the additions by a foreign hand were removed’ by the dealer and restorer William Freeman.36 The Freemans were a local family firm of gilders and carvers, print-sellers and picture restorers who were closely associated with Crome. This rejoining and lining of the canvases must have occurred before 1840, by which date it had been sold to Yarmouth iron-founder William Yetts,37 who owned the painting until it entered the national collection in 1863. The lining process not only served to join the pieces but also to assist in the repair of damage to the original canvas in the upper right corner.38 The edges of each section of canvas were trimmed a little before the lining, and a few millimetres have been lost from the join. There is no complete history of the painting’s surface treatments, but it is known that varnish was removed during treatment in 1961. In 2012 Mousehold Heath was cleaned and restored in preparation for display at Tate Britain, London.39

Fig.23

Mousehold Heath photographed in raking light from the left side

Photography © Tate

Condition

The physical appearance of Mousehold Heath has undoubtedly altered in the course of its history, a consequence not only of the natural ageing characteristics of Crome’s chosen materials, but also of the painting’s early conservation treatments. The heat and pressure used when lining paintings can lead to the flattening of peaks of impasto and additional texturing where the original canvas weave pattern becomes emphasised. Here the lining appears to have been executed quite carefully, if a little unevenly, as there are some patches in the central foreground that appear too smooth and at the left side there is some emphasis of the vertical weave, an effect heightened by darkened residues of old varnishes that have settled into the hollows.

With the passage of time, resinous additions to the oil paint medium can lead to surfaces becoming obscured by yellowing and hence darkening, degradation, cracks and drying defects, a process accelerated by the effects of past treatments. However, unlike the surfaces of some of Crome’s other paintings, that of Mousehold Heath appears in reasonably good condition. Glazes and the remains of early varnishes have remained translucent and the small-scale network of age cracks is not particularly disfiguring. It is, however, difficult to ascertain the impact of the changes that have undoubtedly occurred. Due to their resinous medium, glazes are susceptible to harsh cleaning and smaller lake pigment particles are likely to have faded from both glazed and opaquely painted areas. In the foreground at the lower right corner, the landscape appears extremely sketchy and may have suffered from the loss of such toning glazes. In its recent treatment, later varnishes were carefully thinned but not fully removed in order to preserve these original glazes.