It is well known that Crome and his contemporaries in Norwich depicted Mousehold Heath and similar local landscapes relatively frequently. While contemporary agricultural theorists found nothing in heathland to recommend it and regularly bracketed heathland and common land together as obstacles to the improved agriculture of enclosure, painters found intriguing qualities in both. When Norwich School artists took Mousehold Heath as a subject they were, therefore, portraying a landscape that fell outside of economic calculations of worth and making another reckoning of value, one that responded to something beyond the cash nexus and celebrated what orthodox agricultural thinking decried. Their presentation of these locations therefore prompts a number of further questions. What artistic challenges did heathland present? Was the Norwich School’s attention to this kind of landscape unusual within the broader context of early nineteenth-century British art?1 Was their representation of it accurate or idealised? Should Crome’s Mousehold Heath, Norwich c.1818–20 be distinguished in motive, ambition or achievement from paintings of the heath produced by other artists in Norwich?

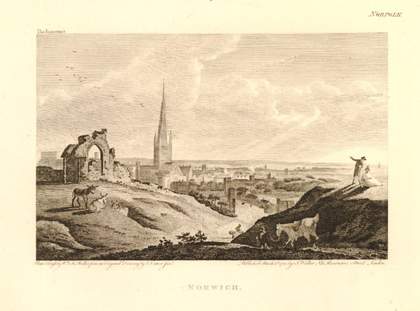

Mousehold Heath, even in its post-enclosure and truncated state, remained a well-known and popular place of recreation for the inhabitants of Norwich. From its elevated position it still provided a good vantage point for views of the city and the countryside beyond, as seen in Charles Catton junior’s watercolour A View of Norwich, from Mousehold Hill, near the ruins of Kett’s Castle 1790 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London), which was engraved by William and John Walker in 1792 (fig.1).2

Fig.1

John Walker after Charles Catton junior, Norwich

Engraving from The Itinerant, published 1 March 1792

British Museum, London

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Looking in the other direction, its terrain was singular: a heathland landscape, with its banks of sand and gravel, sparse tree cover, windmills and extensive panoramic prospects. These features offered painters an alternative to the conventional classical landscape ideal, where the artist would typically introduce clumps of trees to frame the composition and where the landscape was frequently manipulated to evoke Arcadian peace and harmony, typified by indications of luxurious nature and bountiful agriculture. A heath, in contrast, was a much more barren environment and the introduction of the characteristic pictorial devices used in idealised landscape would have entirely falsified its presentation. However, it was not a landscape type for which no artistic models or precedents existed, for some of its features could be seen as very broadly akin to the kinds of terrain some seventeenth-century artists from the Netherlands had made their own. The Dutch school of landscape painting included numerous examples where a relatively flat tract of country unrolled panoramically without obvious framing devices, as well as others where a sandy landscape was contrasted with extensive skies above. The work of Jacob van Ruisdael, Philips Koninck, Jan Wijnants and Jan van Goyen provide good instances of this approach to landscape painting which was, by comparison with the classical ideal, much more realistic in its attention to actual landscape features and the atmospheric particularities of northern weather – see, for instance, Ruisdael’s Panoramic View of Haarlem, Holland c.1670 (City of London Corporation, London) and Wijnants’s Peasants Driving Cattle and Sheep c.1665–70 (fig.2).

Fig.2

Jan Wijnants

Peasants Driving Cattle and Sheep c.1665–70

National Gallery, London

The Dutch tradition had already inspired the young Thomas Gainsborough’s landscapes of neighbouring Suffolk, for example in his Landscape with a View of a Distant Village (c.1748–50; National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh). Representative examples of Dutch paintings could be found in Norfolk collections that were familiar to members of the Norwich School, Crome among them, and they would prove equally inspirational.

Although the Norwich School produced numerous treatments of Mousehold Heath, heathland scenes were not the unique preoccupation of Norwich artists. In the same decades when Mousehold Heath was first being employed as a sketching ground and as the subject of significant paintings in Norwich, one can point to a parallel interest in this kind of terrain elsewhere in England. For example, the contrast between heath and sky, making use of the relatively blond colouration of sand and gravel to produce a light foreground, was employed by William Mulready in three small oil sketches of Hampstead Heath made in 1806 (fig.3), with the artist’s low viewpoint producing a high horizon and a sharp contrast of sky against ground.3

Fig.3

William Mulready

Hampstead Heath 1806

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.4

J.M.W. Turner

Sketch of a Bank, with Gipsies ?exhibited 1809

Tate N00467

Photography © Tate

J.M.W. Turner did not produce any major painting with heathland as its subject, but his Sketch of a Bank, with Gipsies ? exhibited 1809 (Tate N00467; fig.4), which is probably the picture of this title that he exhibited in his own gallery in 1809, also makes use of that compositional device of a low viewpoint, a heightened contrast of ground with sky and the silhouetting of figures against a near horizon.4

John Constable took a similar inspiration from Hampstead Heath in his A Bank on Hampstead Heathc.1820–2 (Tate N02658; fig.5), Sandbank at Hampstead Heath 1821 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London) and Branch Hill Pond, Hampstead Heath, with a Boy Sitting on a Bank c.1825 (Tate N01813). In all of these the colour of the sandy ground is offset by the cloudy sky above, while in the first two examples the view is predominantly concerned with the texture of sand, gravel and scrubby vegetation in the foreground, with a partial view of tracks winding over the heath on the right.

Allied concerns are explored in William Turner of Oxford’s oil painting Gravel Pit on Shotover Hill, near Oxfordc.1818, held in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (fig.6). The location is three miles east of Oxford and he painted it on a number of occasions, exhibiting a watercolour, Shotover Hill, Oxfordshire, at the Society of Painters in Water-colours in 1827.5 The Ashmolean’s painting explores in some detail the excavation of the deposits at the gravel pit and contrasts this sandy foreground with the green pasture above it and the extensive prospects beyond, over which summer clouds are billowing. Interest in similar sites can be found in later-nineteenth-century works such as William Müller’s Sand Pits, Hampstead Heath 1843 and George Vicat Cole’s Cross Roads over the Heath1859 (both Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, Bristol).

Fig.5

John Constable

A Bank on Hampstead Heath c.1820–2

Tate N02658

Photography © Tate

Fig.6

William Turner of Oxford

Gravel Pit on Shotover Hill, near Oxford c.1818

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Not all unenclosed commons were heathlands but they shared the landscape characteristic of large tracts of relatively featureless countryside under wide skies and a number of artists depicted them. William Turner of Oxford, for example, painted several watercolours of the unenclosed sheepwalks on the downlands of Salisbury Plain and throughout his career portrayed the large, open fields and commons of the pre-enclosed landscape, even in his late watercolour Haymaking – A Study from Nature, in Osney Meadow, near Oxford, looking towards Iffley 1854 (private collection). In this same period Peter De Wint was adept at depicting the unenclosed landscape of Lincolnshire. As his widow Harriet De Wint recalled, ‘what a common-place observer would consider flat and unmeaning was in his eyes picturesque. The long extensive distances with their ever varying effects … the cornfields and hayfields … afforded him unceasing delight.’6 Whether his exhibited paintings of such scenes were accurate depictions or a willed fiction is a moot point. Like their contemporaries in Norwich, it is not necessarily obvious whether such scenes bore a faithful witness to the agricultural reality of early nineteenth-century England.7 As the art historian Christiana Payne has noted, artists ‘sometimes chose to make studies of open fields which had not yet been enclosed; or else they deliberately painted the landscape as it had been, rather than in its existing state.’8 Certainly in one instance at least it is evident that De Wint was prepared to retain in a painting what had disappeared in reality. His painting A Cornfield c.1815 (fig.7) is probably the picture of the same name he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815. It shows an unenclosed landscape stretching far into the distance under an extensive sky. The duplicate that De Wint made of this painting has a longer title, Lincolnshire Cornfield, near Horncastlec.1813–26 (Usher Gallery, Lincoln), and this has allowed researchers to compare his painting with the history of the precise area it depicts. It is now agreed that De Wint’s picture, despite its apparent fidelity, is not an accurate record of the Horncastle countryside, for all the parishes in this locality had had their commons enclosed some thirty years before he began work on the painting.9 Moreover, as Payne has remarked, the harvesting scene shown here has had compressed into one moment activities that were quite distinct and were spread over many days.10

Fig.7

Peter De Wint

A Cornfield c.1815

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Nevertheless, although paintings like these share with depictions of Mousehold Heath an interest in unenclosed land, their concentration on harvest and busy labour is of a different order entirely to the imagery of Mousehold Heath, where no crops are visible, animals are scanty and the human presence is minimal. The Norwich School’s representation of the heath makes of it a very particular landscape and simply by dint of its prominence in these artists’ immediate locality they collectively produced more pictures of this kind of environment than their contemporaries elsewhere. Moreover, they had something of a monopoly on its representation; as the Redgraves had noted, Norfolk was ‘a remote angle of the kingdom, seldom visited for its scenery’ and when considering depictions of Mousehold Heath it is striking how very few artists from outside the county attempted to represent it.11

In reviewing the Norwich School’s depictions of Mousehold Heath it seems fair to say that the majority of these pictures were concerned with the unenclosed rump of it that still remained after the enclosures at the turn of the nineteenth century. Landscape features, such as the distant silhouettes of prominent buildings in Norwich, identifiable windmills or the ruins of Kett’s Castle indicate at once that the location is reasonably close to the city. Nevertheless, it is also clear that by choosing viewpoints that omitted these landmarks, especially those prospects that looked away from the city, Mousehold Heath could be presented as a landscape of much greater extent than it actually was. This is particularly true of a dozen undated watercolours, now in Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, painted by Obadiah Short.12 Short was born in Norwich in 1803, was orphaned at the age of five, grew up in extreme poverty and earned his living as a weaver. At the end of the 1820s he made the acquaintance of a circle of art enthusiasts in Norwich who helped him develop his talents as an artist, but it seems that he had little time to practise his art and his production was limited.13 These watercolours most probably date from the 1830s or later. They are varied in their topographical reference, two showing the skyline of Norwich looming over the heath, seven showing barns, windmills and brick-kilns within the landscape, and three presenting the heath as a boundless expanse with trackways rising and falling as they cross it (figs.8 and 9).

Fig.8

Obadiah Short

Sketch of Mousehold Heath undated

Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich

© Norfolk Museums Service

Fig.9

Obadiah Short

Sketch of Mousehold Heath undated

Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich

© Norfolk Museums Service

Short was too young to have remembered the heath in its pre-enclosed prime, so these watercolours, which in any case seem to be the product of direct observation, cannot be considered a nostalgic reverie of Mousehold Heath as it had been. Nevertheless, his vantage points in these watercolours present the heath as though agricultural enclosure and the building of new villas had not affected it, showing it empty of activity and seemingly boundless in extent. The historian and educator Thomas Arnold visited the heath in the early 1830s and he, too, noted how the viewpoint was crucial: what one experienced depended on where one was standing. Remembering how abruptly one’s sensations could change, he wrote of

that point in Mousehold Heath where, when we stood in one particular spot, all human habitations were shut out from our view, – but by a single step we came again within sight of them, and lost the image of perfect solitude.14

The significance of this for Crome’s Mousehold Heathis obvious, for it suggests that, seen from a particular viewpoint, something similar to the wide panorama of heathland in Crome’s painting could have been experienced even after enclosure.

Fig.10

John Sell Cotman

Mousehold Heath, Norwich 1810

British Museum, London

Fig.11

John Sell Cotman

Mousehold Heath, Norwich c.1810

Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich

© Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service

John Sell Cotman’s approach to Mousehold Heath adds weight to this supposition. In the 1810 exhibition of the Norwich Society of Artists he showed a watercolour of Kett’s Castle, which was also part of the heath, and two watercolours with the title Mousehold Heath. At least one and probably two of the three Cotman watercolours now titled Mousehold Heath correspond to those exhibits. All of them show the wide, irregular trackways that crossed the heath and that sense of the landscape undulating into a seemingly endless distance. Two of them include a flock of sheep, one a scattering of cows. In all of these images of Mousehold Heath the pattern-making possibilities of the light-toned trackways against the darker grass seem to have attracted Cotman. He presents the heath as a mosaic of contrasting colour and tone, especially in combination with the emphatic cloud forms he introduced in the sky in two of the watercolours.

In the British Museum’s watercolour a ploughed field in the right foreground and a hedged field in the mid-ground on the left indicate that enclosure has made inroads here (fig.10).15 The other two watercolours, both in Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, are also dated c.1810 but these show no signs of the heathland’s transformation (for an example see fig.11). Even bearing in mind that Cotman was no mere topographer, the difference between these three watercolours reinforces the idea that the viewpoint adopted was crucially important, allowing the artist to portray Mousehold Heath with or without recognisable signs of its improvement by enclosed fields.

Fig.12

John Crome

A Windmill near Norwich c.1816

Tate N00926

Photography © Tate

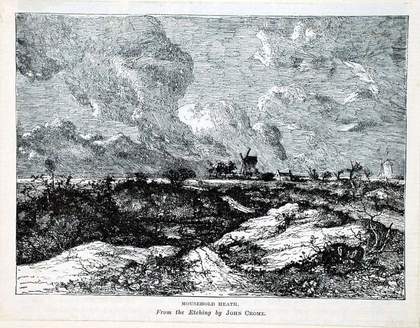

Many of the other Norwich painters frequented Mousehold Heath. Robert Dixon, John Thirtle, Thomas Lound, James Stark, John Middleton, Henry Ninham, George Vincent, John Berney Crome and John Joseph Cotman all used it as a sketching ground, some of them showing pictures of it at the annual exhibitions of the Norwich Society of Artists or selling directly to clients. Crome’s interest in heathland landscape seems to have been the most consistent of all of them, especially if one adds to his Mousehold subjects his pictures of other Norfolk heathlands, such as Poringland, Pockthorpe and Hautbois, as well as those that are simply titled Heath Scene and others, such as the picture now known as A Windmill near Norwich c.1816 (Tate N00926; fig.12), whose titles do not indicate that heathland is their subject.16 Crome’s etching of Mousehold Heath from c.1810–11 (fig.13) is justly famous as his most impressive production in that medium, vying with Rembrandt’s etched landscapes for its grandeur of conception.

Fig.13

John Crome

Mousehold Heath undated (c.1810–11)

Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich

© Norfolk Museums Service

Crome’s mature art was essentially concerned with the experience of landscape rather than topography in a strict sense. It is possible to gather some measure of what this means by comparing Crome’s Mousehold Heath painting with the engraving after Catton’s watercolour of Norwich (fig.1). Both pictures share the same device of abrupt transitions from the foreground to the mid-ground, with figures cut off by an intervening contour. Both have figures on the right directing our gaze towards the horizon, where a cloudy sky is animated at the left by a flock of birds. But here the comparison ends. Catton’s image is a straightforward topographical view and its ingredients are relatively formulaic. By contrast, Crome takes these ingredients and in effect uses them to disrupt expectations. The occluded transitions from the foreground to whatever lies beyond it do not resolve into a prospect that focuses the eye, as does Norwich cathedral in Catton’s view, but merely encourage us to follow the winding tracks as the land rises and falls towards the distant horizon in a seemingly endless rhythm. Likewise, while the pointing figures in Catton’s view are surrogates for the viewer, directing our attention to the significant features of the cityscape beyond, their equivalents in Crome’s painting do not appear to be pointing at anything in particular, or at least nothing discernible. Of course, on one level, by having these two figures gesture towards the horizon Crome employs them to emphasise the sense of depth his painting encompasses. In addition, however, it seems legitimate to propose that their enigmatic pointing is intended to signal distance in the abstract, to direct our imagination beyond what is actually in view. As is shown by a later reminiscence of the heath published in 1833, the feeling that one was in a seemingly unbounded tract of landscape was an important constituent of the experience of the heath in its prime.

Even Mousehold is no more, which in my boyhood was such a glorious moor. The extent of Mousehold was to me the mystery of infinity; I never could reach the end of it; I did not know that it hadan end; and beyond it?– imagination never conceived the beyond of Mousehold.17

The fact that Crome decided to paint this view on such a big canvas is also significant. At 1099 x 1810 mm it is the largest painting he ever produced. He had started work on another comparably sized painting shortly before he died (Yarmouth Water Frolic1821, Kenwood House, London, which measures 1060 x 1727 mm), but none of his canvases before Mousehold Heathwere so amply conceived, the biggest being Slate Quarriesc.1802–5 (Tate N01037; 1238 x 1588 mm), Blacksmith’s Shop, near Hingham c.1808 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; 1540 x 1219 mm) and Marlingford Grove 1815 (Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight; 1365 x 1003 mm). Mousehold Heath remained unsold in Crome’s lifetime, and according to the writer and art scholar Laurence Binyon ‘it was done, not as a commission, but for the painter’s own pleasure “for air and space.”’18 Nevertheless, it is at least worth asking whether this is likely; given the size of the canvas and the work involved in painting this composition it would have represented a major distraction from Crome’s regular production of pictures. Crome sold relatively few works over his career, making his main living as a successful drawing master, but embarking on such a major painting for his own pleasure alone suggests a confidence in his financial position that outsiders might not have shared so readily. Moreover, such a statement implies that the painting was not destined for sale, perhaps not even for public exhibition, but would remain in the artist’s possession as a private meditation on this landscape. Considering the size and ambition of the picture, this is surely debatable.

This query about the painting’s public or private status provokes another question about the approach to the landscape that Crome took. Whether or not it was intended for public viewing, is this a painting engaged in a public discourse, given that Mousehold Heath’s transformation was common knowledge in Norwich? In other words, should it be seen as conditioned by or participating in the discussions in Norwich concerning the improvements offered by enclosure? The landscape depicted here is not enclosed. In the bulk of the composition there are no hedges, fences or obvious field boundaries and thus no fields to speak of; nor are there any improved roads or highways cutting through the open heathland. The rural activity Crome paints, such as it is, is pastoral in character, although it is possible that the land on the horizon at the far right of the painting may represent more regular, cultivated fields fringing the heath. Is the painting therefore a monumental but nevertheless plausible view of the unenclosed remnant of Mousehold Heath, close to the city, with Crome choosing for his subject a vantage point that minimised the signs of enclosure, a procedure akin to the kinds of views Obadiah Short would soon be making? If so, should it be considered a disinterested portrayal of what was left of Mousehold Heath, or is it a nostalgic exercise, an imaginative painting of Mousehold’s original vast expanse, before it was enclosed? As the art historian Ian Waites has pointed out, Crome’s majestic painting The Poringland Oakc.1818–20 (Tate N02674; fig.14), painted at about the same time as Mousehold Heath, shows what looks like unimproved heathland behind the eponymous tree, although it was painted some thirteen years after the parish’s commons had been enclosed.19 If that is the case, it is possible that Crome may have envisaged his painting of Mousehold Heath in the same spirit, deliberately ignoring the topographical reality of the improved agricultural landscape of Norfolk.

Fig.14

John Crome

The Poringland Oak c.1818–20

Oil on canvas

1251 x 1003 mm

Tate N02674

Photography © Tate

In the most thorough analysis of Mousehold Heath published to date, art historian Trevor Fawcett wrestled with the same problems, concluding first that ‘by suppressing any overt reference to agricultural improvement, by choosing this particular prospect, the artist has in fact intensified the nostalgic and idealizing character of the painting.’ But he immediately qualifies that perception by suggesting that Crome was, at bottom, less concerned with ‘the direct observation of a particular landscape, nor even with its purely aesthetic or picturesque qualities. He is rather feeling towards a new register of his art, the expression of the sublime.’20 In other words, Crome was concerned not so much with the landscape of Mousehold Heath and its uses, historic or contemporary, but much more with the opportunity it afforded him to paint an uninterrupted panorama of countryside under a vast sky. The detail of the foreground plants allows the observer to contemplate nature in its variety and at close-hand, but the immensity of the landscape that lies beyond is something that escapes routine comprehension insofar as it is suggestive of infinity. As Fawcett observes, these kinds of feelings were sanctioned not only in aesthetic theory, where unbounded horizons were deemed to provoke sublime experiences, but also in theological writings, where the deep contemplation of the natural world would lead the sensitive observer to meditations on the nature of creation and the hand that lay behind it – the so-called argument from design. Towards the end of his life Crome added the complete works of William Paley to his library, and Paley’s natural theology was a key source for the argument from design.21

These approaches to Crome’s painting and its ultimate meaning or purpose cannot be definitively assessed on the basis of hard evidence as more or less reasonable interpretations. Both are credible and persuasive, and it may well be, as Fawcett suggests, that the painting should be understood to function on at least these two levels, as a localised representation of a specific place – perhaps seen as it had been rather than as it actually appeared – and at the same time as a more generalised engagement with nature. This interpretative difficulty immediately demonstrates that Crome’s approach to landscape in this painting is more complex than what one finds in the landscapes painted by his colleagues in the Norwich Society of Artists, whose vision of landscape was less profound. Of all of them, only John Sell Cotman has traditionally been seen as Crome’s creative equal. With Mousehold Heathand other major paintings by Crome, rather than look to the Norwich School for comparison, the proper context is the more general tendencies of this period, where the idea of landscape as a genre that could take on history painting as the most compelling art form was being pursued actively.