The German word Vergangenheitsbewältigung – ‘the overcoming of the past’ – was crucial to the psychological landscape in Germany post-1945. The term itself suggests that grappling with the past is absolutely necessary in order to overcome it and, implicitly, to move beyond it. It could be argued that Anselm Kiefer’s work as a whole can be understood as a form of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, determined by his involuntary status as a member of the German Nachgeborenen generation – those born after the Second World War.1 Thus it could be said that he and his subject matter, which makes repeated reference to Nazi iconography, gestures and events, allude to the potential of its return in future generations.2 In his performance of the Sieg Heil salute in Occupations 1969 and the many photographs of the performance that he titled Heroic Symbols 1969, Kiefer acted as a stand-in for both past and present generations, in an action that functioned at the most intimate personal level in the use of his own body (Tate AR01162; fig.1).

Fig.1

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Photograph, black and white, on paper

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

The state of collective guilt for the atrocities committed by the grandparents, parents and older siblings of the Nachgeborenen characterised the climate of post-war West Germany. Writing in 1945 the Swiss psychologist C.G. Jung described the nature of collective guilt: ‘It cares nothing for the just and the unjust, it is the dark cloud that rises up from the scene of an unexpiated crime. It is a psychic phenomenon, and it is therefore no condemnation of the German people to say that they are collectively guilty, but simply a statement of fact.’3 While this essay, Jung’s first written after the Holocaust, acknowledges the irrational roots of the concept of collective guilt, which he describes in mythic, almost expressionist terms, it also serves to indict the German people as a whole. The ‘psychic phenomenon’ to which he refers depends entirely on nationality and physical locale, thus affecting future generations originating or living on this soil. This psychobiological view posits a connection between a people, its nation and its history that is deeply familiar from the ‘Blut und Boden’ (in English ‘Blood and Soil’) rhetoric that the National Socialists used to knit together the Volksgemeinschaft (‘people’s community’) and expunge those elements deemed foreign.

The Nachgeborenen faced, and continue to face, the challenge of living in a physically reconstructed but psychically reeling country. Although philosopher Theodor Adorno warned of the ‘ghost of that which was so monstrous, that it did not die by its own death’,4 the art historian and critic Sabine Schütz has pointed out that such works as historian Friedrich Meinecke’s Die Deutsche Katastrophe (in English The German Catastrophe; 1946) and philosopher Karl Jaspers’s Die Schuldfrage (in English The Question of Guilt; 1947) make visible the fact that ‘even after Auschwitz, intellectuals called for the preservation of cultural German patterns of tradition … thus elevating the “denazified” culture again to an instance of moral institution’.5 The ontological quandary of what it is to live as a German in post-war Germany is formulated by Jung as a series of questions: ‘How am I to live with this shadow? What attitude is required if I am able to live in spite of evil?’6 Kiefer not only engages with these questions in his work, but acknowledges that only his birthdate excludes him from first-hand experience and thus refuses to distance himself from the previous generation. As the artist has observed: ‘at minimum, in theory I am counted amongst the perpetrators, because I simply cannot be sure now, what I might have done then.’7 The form of honest self-reflection that Kiefer employs in the Heroic Symbols photographs and their related artist books and paintings invites his audience to consider or reconsider their understanding of past and present events on an immediate, uncomfortably personal level.

Investing the role of the artist with an exorcistic force, it would appear that Kiefer’s ambition was to disturb the semblance of complacent calm or silence and act as an accelerant to the public discussion of questions of collective guilt and mourning. The Heroic Symbols photographic series courted shock in part by examining tropes of National Socialist ideology that themselves stemmed from discourses developed in Germany in the Wilhelmine and Weimar eras (1890–1918 and 1919–33 respectively). The most important include the Blut und Boden idea and philosopher Martin Heidegger’s rather closely related conception of facticity. In his 1998 book Anselm Kiefer and the Philosophy of Martin Heidegger, art historian Matthew Biro explored facticity – the paradox of human free will in the face of socio-historical determinism – by relating its role in Heidegger’s philosophy to Kiefer’s work.8 Biro makes the case for considering the modern movement in Germany as a continuous development untrammelled by the typically applied periodic caesura such as 1918, 1933 and 1945.9 The implication is that just as the shift from Wilhelmine to Weimar Germany did not alter or determine the development of modernity, the shift from National Socialist to post-Holocaust Germany did not entail an immediate change of conditions, ideologies or structures. Although the Wilhelmine reliance on what the historian Mark Jarzombek has described as the ‘theory that the visual world and the ethical world were mimetically related’10 prepared the way for National Socialist cultural theories of a race- and blood-bound art, this eventual outcome was not foreseeable and it continues to function in Kiefer’s work and its reception in Germany.

The explicit focus of the Wilhelmine reform movement that lay at the root of this theory was the rejuvenation of the arts and crafts by such organisations as the Werkbund, founded in 1907. The movement insisted on a new national aesthetic as a normative value with salvific potential in both the cultural and political arenas. Its völkisch-holistic rhetoric and use of traditional tropes that spoke of the German people (Volk) as a mystical, pseudo-biological whole, and the state as an ‘organism’ in which the individual was subsumed within the whole, were appropriated to odious and obvious ends in the National Socialist Volksgemeinschaft.11 Entangled with the theories of blood and soil, it established nationalist and anti-Semitic ideology and differentiated the new National Socialist state from previous German governments. Illustrating this schism, particularly from the Weimar Republic, was crucial to framing the new National Socialist state as at once both a progression from and the return to a past, more pure Germany. This past Germany, imagined among other things as an ideal racial utopia free from social conflict and strife, could be reclaimed, it was suggested, by overcoming the current ‘degenerate’ elements pervading social, political and cultural life. The proposed thousand-year Reich could become this utopia only with a population of racially pure people, both represented in and inspired by their art.

Fig.2

Heinrich Hoffman

Nazis giving the Sieg Heil salute at a Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg, 1928

In order to promote this message and to educate the population, the establishment of a racial ideal was deemed necessary, and art, particularly heroic figurative sculpture, became its mode of illustration and expression. The work of sculptors Arno Breker and Josef Thorak had its cinematic pendant in the films of Leni Riefenstahl and its propagandistic manifestation in the photographs of Heinrich Hoffman (fig.2). Investing art with the capacity to illuminate this new method of inclusion and exclusion based on physical attributes invested with signifiers of racial lineage had the effect of granting both art and the artist significant authority and power. Within this doctrine the trope of the artist-genius was reconfigured, his or her hand guided instinctively and naturally by blood, instead of by intention, tradition, skill or schooling. This new figure was crucial to the production of an entirely new art for the new state and its new people, and presupposed an intuitive communication between the artist and his audience, seeking always to reflect its own soul and the spirit of its time in the work.

The response to Heroic Symbols has shifted significantly from the immediate reaction in the late 1960s and the 1970s, when Kiefer was accused of ambivalence to Hitler at best. Biro identifies Kiefer’s emphasis on ‘linking elements that produce paradoxical or conflicting interpretations to a potentially shared visual perspective’, creating what he terms ‘undecidability’.12 Tracing this method to Heidegger’s philosophy Biro argues that it is employed to illuminate ‘the broad and divergent range of meanings at every moment of their history, by provoking both assent and disagreement’.13 Giving an impression of ambiguity was a politically unacceptable position in late-1960s West Germany. The leftist student movement shook the country in the public spectacle of a generation’s rebellion against its parents, manifested as the infamous protests of 1968 by the so-called ’68-ers and the terrorist activities of the Red Army Faction around Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof. The Nachgeborenen were outraged by the fact that many offices in the judicial or public service sector were reassumed by ‘former’ Nazis after a brief process of ‘denazification’. It is this highly sensitised and politicised audience that Kiefer confronts with symbols laden with emotional and historical significance, deliberately creating situations in which the viewer must take a position. By internalising the Sieg Heil gesture, as the philosopher Pierre Péju has pointed out, the taboo is broken twofold.14 The first is the immediate emotional shock at seeing the gesture performed by a young man in a costume resembling a uniform, photographed from below in an heroic manner. The second is the infringement of the extant § 86a of the German Strafgesetzbuch (criminal code) forbidding the use of hallmarks of unconstitutional organisations, which include both the National Socialist salute and its uniform.15 A first version of the law was passed on 30 November 1945 in Berlin as Article IV of Law Nr. 8, ‘Ausschaltung und Verbot der militärischen Ausbildung’ (‘Elimination and Prohibition of Military Training’) and signed by G. Shukow of the Soviet Union, field marshal B.L. Montgomery, General Joseph T. McNarney and P. Koenig, Armeekorpsgeneral. The original text is of particular significance. It forbids the ‘wearing of German military or Nazi uniforms, insignia, flags, banners or standards or military or civil medals and decorations as well as the use of characteristically Nazi or military forms of salute or greeting’, and in the following sentence decrees that ‘all other symbolic gestures, which express the spirit of Nazism, are forbidden.’16

Within a social climate determined by collective guilt, Kiefer took it upon himself to ask firstly whether he is implicated in past generations’ atrocities by virtue of his nationality and secondly whether he is a National Socialist, either by origin or through the performance of this gesture. With regard to the latter, many critics seem to have concluded that the performance of the salute as a German could mean only that. The critic Werner Spies’s review of the 1980 Venice Biennale, ‘Überdosis anTeutschem’ – translated into English as ‘An Overdose of the Teutonic’ – is a telling, if late, example.17 The irony of this somewhat hysterical response is the implicit, albeit entirely unintentional, affirmation of an autochthonous or Blut und Boden ideology and a failure to recognise Kiefer’s subversion of the racial political subtext assigned to art by the National Socialists. Art historian Lisa Saltzman’s analysis of Kiefer’s reception in Germany posits that the initial misunderstandings of his work as somehow condoning fascism were based not only on his engagement with subjects considered unsavoury and taboo, but on the fear of what an international audience might see in such project.18 The curator and art historian Mark Rosenthal falls into the same pattern in his description of Kiefer’s position as an artist who is ‘content to make a thoroughly German art, of native subjects, values and symbols.’19 Like that of Spies, Rosenthal’s highly problematic classification resonates strongly with the notion that ‘thoroughly German art’ might only be produced by a German artist with the ability to access ‘native’ content, which closely resembles the function of the artist in the Wilhelmine, Weimar and National Socialist political systems. This function was not to express individual experience but rather to reflect a common, national cultural experience or spirit of the times. The artist was cast as medium for national sentiment and, by extension, as crucial medicine for the ailing national body.

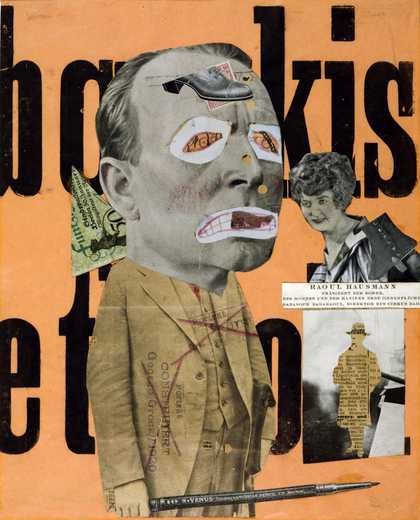

Fig.3

Raoul Hausmann

The Art Critic (Der Kunstkritiker) 1919–20

Lithograph and printed paper on paper

Tate

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016

The cultural historian and theorist Andreas Huyssen’s assessment of the Occupations performance, which is also applicable to the Heroic Symbols photographs, takes a different approach: ‘upon a second look, the artist does not identify with the gesture of Nazi occupations, he ridicules it, satirizes it. He is properly critical.’20 By acknowledging the viewer’s immediate emotional response, Huyssen is able to continue past it. Still, he recognises the very real disjunction that a German viewer experiences when encountering Kiefer’s work and maps the possible sequence of critical thought: ‘even this consideration does not lay to rest our fundamental uneasiness. Are irony and satire really the appropriate mode for dealing with fascist terror? Doesn’t this series of photographs belittle the very real terror which the Sieg Heil gesture conjures up for a historically informed memory?’21 In fact, Kiefer’s examination of his country’s past falls squarely in line with such artists of the early Weimar Republic as George Grosz, Max Ernst, Max Beckmann and Otto Dix. Furthermore, the Cologne dada movement employed art to process and examine the events of the preceding years, drawing on the artists’ experiences of the First World War as well as on the state of post-war, post-Wilhelmine Germany. Their paintings of damaged bodies in derelict urban landscapes placed their audiences into a similarly fraught position, asking them to engage with ironic caricatures and fragmented distortions rife with sarcasm and bitterness. Austrian artist Raoul Hausmann’s photomontage The Art Critic 1919–20 (Tate T01918; fig.3) is an example of the ways in which dadaists used collage to represent this fragmentation and to criticise and satirise current events. The public response to these images is well documented and first manifested as policy in the Weimar Bildersturm – translated literally as ‘storm of images’ – in which works were purged from collections and decried as ‘degenerate’. The campaign led by Wilhelm Frick in the 1930s culminated in the touring Degenerate Art exhibitions later in the decade and the National Socialist art and cultural policies of defamation and destruction.

The German post-war psychological response to the war has been discussed perhaps most famously in Margaret and Alexander Mitscherlich’s The Inability to Mourn (1967). This title has become a catchall used to sum up the post-war phenomenon and describe the difficulty faced by the Nachgeborenen generation. Huyssen expands this theme, arguing that Kiefer’s work is ‘steeped in a melancholy fascination with the past’22 and explaining that ‘if mourning implies an active working through a loss, then melancholy is characterized by an inability to overcome that loss and in some instances even a continuing identification with the lost object of love.’23 In Occupations this lost object of love is the figure of the Führer, carefully established and celebrated by the National Socialists as a triumphant leader. In 1936 Jung identified such a figure as critical to the specific nature of the events in National Socialist Germany. He suggested, somewhat presciently, that a single, obviously ‘possessed’ man ‘infected a whole nation to such an extent that everything is set in motion and has started rolling its course towards perdition’.24 His argument resonates with the cult of personality constructed by the National Socialist propaganda machine. Jung’s understanding of the German pathography is based on the premise that nature and history are related and proposes that the historical German fate is thus an expression of its nature.25 The conception of a passion somehow innately German resonates closely with the Blut und Boden theories that determined the burgeoning Wilhelmine discourses of cultural criticism, eugenics and national identity.

By using the body as a performative instrument, Kiefer engages explicitly with these notions. This challenges the idea that the sentiments motivating the populace during the so-called Third Reich, here represented by a learned physical motion, were left behind in 1945. It suggests instead that they, like the Sieg Heil salute, were deeply entrenched in the collective and its muscle memory, lying dormant and ready to be performed. The performance of this gesture by a single figure is the focus of Kiefer’s staged tableaux. Art historian Charles Haxthausen has argued that in Kiefer’s hands ‘photography, that ostensibly unmediated image of “reality”, becomes a medium of fiction like cinema: the artist is actor and director, his studio functions as the mise-en-scène for a broad range of epics’.26 The interplay of reality and mythmaking in photography is as inherent to Kiefer’s work as it was to that of August Sander in his attempt to compile an ethnographic survey of the German population using portrait photography,27 or to the mythic figure suggested by many of Hoffmann’s Hitler portraits. Yet it is at this intersection that Kiefer’s similarity with filmmaking lies. The viewer encounters the photographs and is unsure what to make of the image, how to respond, and what context might inform the narrative. Many of Kiefer’s photographs imply a sense of impending action and wider story, as if they were film stills. As Haxthausen has described Kiefer’s method: ‘by arbitrarily (and sometimes humorously) determining the relationship between an image and a concept Kiefer invites his audience to reflect on the processes of symbolic signification and appropriation which occur before his eyes.’28

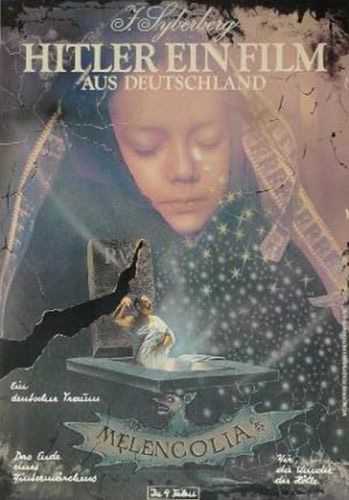

Fig.4

Poster for Jürgen Syberberg’s Hitler: A Film from Germany (Hitler, Ein Film aus Deutschland) 1977

Filmmaker Jürgen Syberberg’s seven-hour epic Hitler: A Film from Germany (in German Hitler, Ein Film aus Deutschland; 1977) follows Kiefer in its focus on gestural appropriation (fig.4). While the figure in Kiefer’s work has been described as resembling a ‘fanatical puppet or desperate child playing games’,29 Syberberg drew on actual puppets, children and circus actors to repeat the gestures and words of National Socialism. As Jung observed in 1945: ‘Hitler’s theatrical, obviously hysterical gestures struck all foreigners … as purely ridiculous. When I saw him with my own eyes, he suggested a psychic scarecrow (with a broomstick for an outstretched arm) rather than a human being.’30 Jung’s differentiation between his own experience as a Swiss national (and that of foreigners more widely) and the experience of the German masses suggests the specificity of the Führer’s appeal. Kiefer has joined in this chorus, giving the perspective of the Nachgeborenen generation: ‘Hitler looks like a comedist. If you didn’t know it was so tragic, so horrible, it looks really ridiculous.’31 This is of course the problem for the German audience, as Huyssen suggests when considering whether sarcasm and irony can be appropriate modes of engagement with such tragedy.32

Syberberg created an epic cinematic narrative in four parts. His reappraisal of National Socialism’s most nefarious characters and events, re-enacted by actors and hand-puppets, takes place within celebrated examples of German culture, including projections of Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s chalk cliffs and alpine landscapes, the infant from Philipp Otto Runge’s painting The Morning 1808 (Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg) and the music of Richard Wagner. In the third minute of the film’s first act, entitled The Grail, the narrator proclaims: ‘dances of death, dialogues of death, dialogues in the land of the dead, a hundred years afterwards, a thousand years, a million years’33 and follows shortly with the question: ‘Whom does the world hold guilty? And what would Hitler be without us?’ The narration fades into a rendition of the national anthem ‘Deutschland Über Alles’ (‘Germany Above All’).34 The interminable nature of collective guilt, the question of whom to blame and accusations levied at those who supported Hitler (either actively or by their passive acquiescence) as addressed in Hitler, Ein Film aus Deutschland creates a continuance of Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols project in film.

Moving beyond Kiefer’s implicit inquiry, Syberberg’s film presents concrete statements: ‘This is about us, all of us, it’s about the happiness we were promised and never given. It’s the people who elected him and sacrificed everything for him, themselves and their lives, sons, fathers, friends and their images of their world, cities, whole countries, their conscience and their souls.’35 Like Kiefer, Syberberg refused any attempt to move on, to repress and deny the country’s history. Despite the scale of his narrative he sought an intimate, personal connection, addressing the audience directly: ‘It’s about the Hitler within us on a small budget, without sets, with slide projections and our imaginations where everyone can join in.’36 Syberberg invites the audience to become a part of the meaning and mythmaking, to consider or identify their own actions and to join in the production. Inviting the viewer to participate as an artist is a tacit acknowledgement of the importance of the arts to National Socialism. As the character Hermann exclaims: ‘When I hear the word culture, I reach for my pistol, that’s the art for the people that we want. Our cultural revolution is for a more popular art, an art of the people. Art is an exalted mission, which demands fanaticism … We pay with our lives for art.’37 The fanatical and myopic focus on art in the German political landscape, and the tragic irony of this statement in light of subsequent events, is illustrated by Syberberg’s list of cultural figures who committed suicide. It includes Walter Benjamin, Kurt Tucholsky, Stefan Zweig and Martha Liebermann, the wife of the Impressionist painter Max Liebermann, and ends in an evocative summation: ‘And, and. No End. Never. How to explain, tell, understand it. And do nothing? Just silence?’38

The response to Syberberg’s film went beyond the realm of film criticism and focused on his depiction of and relationship to history,39 engendering an intellectual curiosity outside Germany not unlike Kiefer’s reception. Syberberg’s was a reception that film critic Klaus Eder has argued was like few other West German cultural achievements.40 Although it remains a singular project, it exists within the broader development of West German political film. Media historian Anton Kaes has examined the important role film played in the communal Vergangenheitsbewältigung:

All of us, whether or not we have lived through the Hitler era, have partaken of its sights and sounds in a host of documentary and feature films … History it would seem has become widely accessible, but the power over memory has passed into the hands of those who create these images. It is not surprising that in recent years we have witnessed a virulent struggle over the production and administration of public memory.41

Kiefer’s work helped to address this wider struggle, also exemplified in film by Edgar Reitz’s Heimat (in English Home) series of 1984, Michael Haneke’s Das Weisse Band. Eine Kindergeschichte aus Deutschland (in English The White Ribbon, a German Children’s Story; 2010), and by the work of such artists as Georg Baselitz and Gerhard Richter.

Writing on the events unfolding in Germany in 1936, Jung described archetypes as: ‘like riverbeds which dry up when the water deserts them, but which it can find again at any time. An archetype is like an old watercourse along which the water of life has flowed for centuries, digging a deep channel for itself. The longer it has flowed in this channel the more likely it is that sooner or later the water will return to its old bed.’42 Three decades after Syberberg’s film and over four after the Heroic Symbols photographs were taken, it is clear that these artists’ insistence on discussion and consideration of these loaded archetypes was crucial to the establishment of a point of access that circumvented horror and devastation and moved towards critical understanding.

The German performance artist Jonathan Meese performed the Sieg Heil salute at a podium discussion organised by the journal Spiegel entitled ‘Megalomania in the Art World’ that ran alongside Documenta in Kassel on 4 June 2012. Meese performed it again in Mannheim on 26 June 2013, during a two-hour performance entitled Generaltanz den Erzschiller.43 The ensuing lawsuit, brought against him for the ‘use of attributes of unconstitutional organizations’,44 illustrates not only the Sieg Heil gesture’s continued shock value, but the continued power of National Socialist history in German culture and politics. The continued relevance of Heroic Symbols, cited in the German press as a direct precedent to Meese’s performance,45 is due in large part to the ‘undecidability’ of the image it presents to us and the recurrent question as to what to do next.46