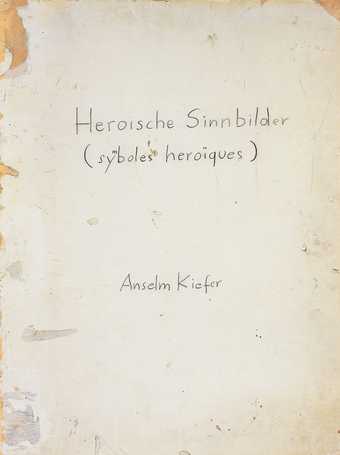

Some of the provocative Heroic Symbols photographs that Anselm Kiefer created to document his 1969 Occupations performance while a student at Karlsruhe were incorporated into two closely related artist books produced later that year: Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) and For Jean Genet (Für Jean Genet). Both are particularly large, measuring more than two feet in height, and they possess a ‘low art’ appearance – crudely bound and akin to scrapbooks in the way that they juxtapose original photographs and small watercolours with found images taken from Nazi magazines.1 Slightly different photographs of the Occupations performance were utilised in each of the two books. Each book is unique: they were not published in an edition, although a few iterations do exist. For instance, versions of Heroic Symbols can be found in the Würth Collection, Künzelsau, and the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, as well as in private collections. There is a further version of the project that is divided into Heroic Symbols I and Heroic Symbols II. The photographs in the ARTIST ROOMS collection owned by Tate and National Galleries of Scotland relate to both the Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet books.

Fig.1

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969 (cover)

Forty-six-page book with watercolour on paper, graphite, original and magazine photographs, postcards and linen strips mounted on cardboard

664 x 510 x 85 mm

© Anselm Kiefer

Würth Collection, Künzelsau

Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

Image courtesy of Heiner Bastian Fine Art, Berlin

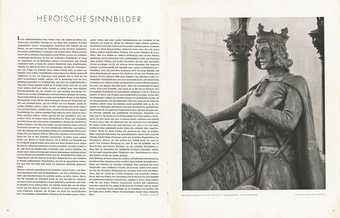

Fig.2

Cover to the February 1943 issue of Die Kunst im

Deutschen Reich

The title Heroic Symbols (fig.1) is derived from an article by the Nazi art theorist Robert Scholz that was published in the February 1943 issue of Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich (in English Art in the German Reich). This was the official National Socialist arts magazine, edited by Alfred Rosenberg (and from 1943 with Scholz as Chief Editor), copies of which were owned by Kiefer’s father (figs.2 and 3). The cover design since the first issue in January 1937, when the magazine was known as Die Kunst im Dritten Reich (in English The Art of the Third Reich; the title was amended in 1939), was by Richard Klein, an artist of high standing in the National Socialist regime who was on the advisory board of the journal and who specialised in producing Nazi emblems, medals, trophies, stamps and all manner of ‘heroic symbols’. The same design of an imperial eagle bearing a swastika wrapped in an oak wreath, connected to a burning torch and the helmeted head of Athena/Minerva, was also the logo of the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibition), which was staged eight times from 1937 to 1944 in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich. The French translation in parentheses (‘symboles heroïques’) on the cover of Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols book points both to the artist’s keen interest in the French language and to the fact that a French edition of this Nazi magazine was published in France during the German occupation.2 The translation symboles heroïques also appears as a caption for the photographs in For Jean Genet, indicating the connections between these book projects.

Fig.3

Double-page spread from the February 1943 issue of Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich

The particular issue of Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich that inspired the title of Kiefer’s 1969 book opens and closes with photographs of works by Arno Breker, Hitler’s favoured sculptor. An imperial Eagle sculpture (known in German as a Reichsadler) by Breker ‘greets’ the reader on the opening page, accompanied by a short extract of a January 1943 speech by Hitler in which he compared the mission of German soldiers fighting on the Eastern front to that of the Teutonic knights. This sense of historical continuity with a German medieval military order is visually articulated in the illustrations that follow Scholz’s one-page essay that also amplifies this theme, starting with a photograph of the Magdeburg Rider, the oldest German equestrian statue (c.1240), representing Otto the Great, who unified German tribes into a single kingdom. Other artworks reproduced in this issue – all of which Scholz argued constituted a German genealogy of ‘heroic symbols’ – included Franz von Lenbach’s oil painting of Otto von Bismarck from c.1890 (accompanied by extracts from his Reichstag speeches, as well as visual examples of how the heraldic Reichsadler had changed since 1500), Johann Gottfried Schadow’s 1791 neoclassical sculpture of Frederick the Great, a marble bust of Queen Louise of Prussia from 1806 by Schadow’s pupil Christian Daniel Rauch and an equestrian painting by Simon Meister of General Field Marshal Gebhard Blücher created in 1823.

In the eponymous ‘Heroische Sinnbilder’ (‘Heroic Symbols’) article in Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich, representations of such historical personages are included among photographs of other patriotic paintings, portrait busts, iron crosses and photographs of military memorial monuments, such as the Tannenberg Memorial completed in 1927 in a shape reminiscent of both Stonehenge and the castles of the Teutonic knights. The issue ends with a reproduction of a 1938 wall relief by Breker entitled Vergeltung (in English Retaliation), which features a heroic musclebound athletic figure that in some ways recalls the neoclassical style of Schadow and Rauch but in a manner that curiously verges on the homoerotic in its eugenic nudism. It is one of a number of ‘heroic symbols’ created by Breker for Hitler’s unrealised Hall of Soldiers designed by Wilhelm Kreis in 1939, a design that Kiefer would also reference in large-scale woodcuts from the early 1980s onward.

Kiefer’s appropriation of found photographs from Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich and other National Socialist publications for his 1969 book projects, often pasted alongside his own photographs and watercolours, does not suggest that he closely identified with the aesthetics of National Socialist ideology. However, it does imply his refusal to participate in a collective process of brushing under the carpet the tainted patriotic symbols of the past and a need to engage with the motivations of his father’s generation in order to comprehend what had happened to Germany. In so doing, the artist attempted to confront the sphinx of German identity, deconstructing the canon of heroes in German cultural history, in particular signalling how the Nazis called upon and misused the past in order to legitimate their own extreme nationalistic and warped worldview. Often evidenced through his use of roll-call inscriptions and ensemble portraits, the construction and deconstruction of ‘halls of heroes’ has been a characterising trait of Kiefer’s work from the very outset of his career, beginning with the creation of his 1969 book Heroic Symbols.

Furthermore, the artist also appropriated photographs from Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich and other Nazi publications in a number of other artist books, and not just for Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet. A particularly intriguing example of such appropriation is Das deutsche Volksgesicht, Kohle für 2000 Jahre 1974 (Hall Art Foundation, New York), which involved Kiefer altering the physiognomic photographs made by the National Socialist photographer Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, merging her faces of Aryan peasants with the grain of the wood using an experimental woodcut and frottage technique. Kiefer is a great admirer of the typological Neue Sachlichkeit photography of August Sander, but is highly critical of the eugenics-driven ‘Faces of the Volk’ photobooks of peasant types made by Lendvai-Dircksen and others who were close to the Nazi regime.3 In this work Kiefer appropriated and manipulated her photographs in order to expose the absurdity of such reactionary aesthetics.

Kiefer sometimes wrote suggestive or short ‘descriptive’ captions in the pages of his artist books, but his early books were essentially visual rather than textual. To be precise, they were ‘deskilled’ photoconceptual projects, and in the case of Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet, they were books that documented a performance. As the art historian Benjamin Buchloh has observed, although these projects were situated in an ‘explicit dialogue with the photoconceptualist and performance practices of the sixties’, the work re-orientated these practices ‘within a tainted context of German historicity’.4 Furthermore, the books can be understood as incubators for many ideas later executed by Kiefer on a larger scale in various media.

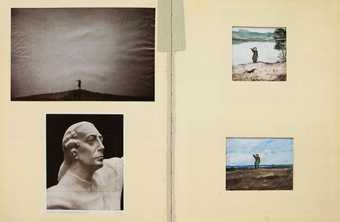

Fig.4

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969 (pp.10–11)

© Anselm Kiefer

Würth Collection, Künzelsau

Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

In the Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet books the artist almost presents himself as a toy soldier performing the salute. This is particularly evident in the small caricatural watercolours based on photographs of the Occupations performance, paintings that possess, by virtue of the medium’s fluidity as well as Kiefer’s lyrical handling of the paint, a dreamy, whimsical quality that undermines the seriousness of the forbidden gesture (fig.4). Watercolour, a medium Kiefer has used since childhood, was eminently suitable for a project that represented but deflated the aggressiveness of the Sieg Heil. The softness of the medium is matched by the childlike nature of the saluting figure depicted, who seems dwarfed by his surroundings, a diminutiveness emphasised by the grown-up attire of an overcoat and riding boots. Furthermore, this figure subverts the masculine rigidity of the Hitlergruß (Nazi salute) by giving an ‘incorrect’ limp-wristed gesture rather than an erect salute. In the Heroic Symbols I book these watercolours are positioned opposite a found photograph of a 1940 neoclassical equestrian monument of Friedrich II (cropped to focus on the head, shoulders and outstretched arm) by the National Socialist sculptor Josef Thorak, and a long-shot photograph of Kiefer again giving the Hitlergruß – an image that brings to mind the isolated figures and sublime horizontal expansiveness of Caspar David Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea 1809–10 (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin), Gustave Courbet’s The Beach at Palavas 1854 (Musée Fabre, Montpellier) and James Abbot McNeill Whistler’s Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville 1865 (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). Here, however, the isolation of the Romantic artist situated in an immense nothingness is disturbed by the caricatural figures on the opposite page.

Fig.5

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969 (p.8)

© Anselm Kiefer

Private collection

Photo: Charles Duprat

Fig.6

Max Klinger, printed by Otto Felsing

Abandoned from the series A Life 1884

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

Photographs and watercolours of Kiefer saluting on the banks of the Rhine appear in Heroic Symbols I (fig.5), bringing to mind Max Klinger’s etching Abandoned from the series A Life, Opus VIII of 1884 (fig.6), which itself owes much to Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea, and the same melancholic sense of isolation in nature in Klinger and Friedrich is evident in Kiefer’s work. Kiefer was brought up in a small Black Forest village not far from the Swiss and French borders. He has said: ‘Because of the history and geography I was driven to French culture. And the Rhine would flood every spring so the border never seemed fixed, although I couldn’t cross it. France lay behind this moveable frontier and was quite enigmatic because I couldn’t go there but it was there. In effect it was the promised land, but not because of the physical state of Germany’.5

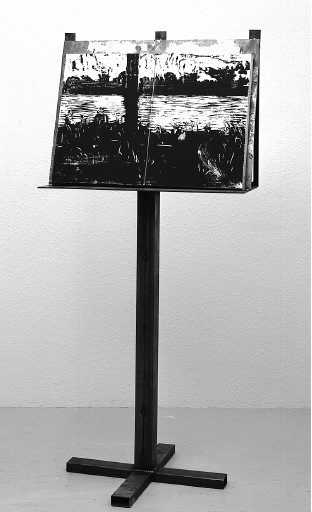

Fig.7

Anselm Kiefer

The Rhine (Der Rhein) 1981

Metal lectern, Perspex and book with woodcuts on paper

Tate

© Anselm Kiefer

In one of the photographs by the Rhine featured in the Heroic Symbols book projects Kiefer’s head is bent forward and his posture lacks the rigidity normally associated with the Sieg Heil. Compositionally, his body seems squeezed down by the bank on the other side of the river, perhaps humbled by the emotion of shame and a sense of collective guilt, but the image is ultimately ambivalent and could be given another reading altogether. For instance, the art historian Matthew Biro has argued that ‘Kiefer’s arm appears to move the horizon, making space for his figure and suggesting that through his will he can mold his environment – an association that could be read as glorifying the power of the Nazi state’.6 However, Biro ultimately still believes that the Rhine photographs are ‘critical’ rather than ‘affirmative’ and effectively indicates how such work could be misinterpreted. The sequence entitled ‘On the Rhine’ in these artist books is important because, like so many other scenarios played out in these early books, it is the original source for later projects, including large-format woodcuts for a 2013 Louvre exhibition De l’Allemagne 1800–1939, and woodcuts and woodcut collages of the 1980s and 1990s such as Kiefer’s book entitled The Rhine 1981 in the Tate collection, which shows the process of the river flooding its banks (Tate T04128; fig.7).

Flooding is also an important idea for Kiefer and relates to the Wagnerian tales that feature so much in his art from the 1970s onward. Ever present as an underpinning concept in his work is the final opera of Wagner’s Ring cycle, Die Götterdämmerung (1876), when Brünnhilde demands a funeral pyre to be built for Siegfried by the side of the Rhine, a flaming pyre into which she rides her horse Grane that causes the Rhine to overflow and allows the Rhine maidens to retrieve their precious ring. In giving a salute by the much-mythologised Rhine in the Heroic Symbols photographs, Kiefer was signalling how such myth had been appropriated by the National Socialists,7 an idea reinforced in later woodcuts of 1980–1 when the banks of the Rhine fictively support an architectural image – that of Kreis’s 1939 Hall of Soldiers.

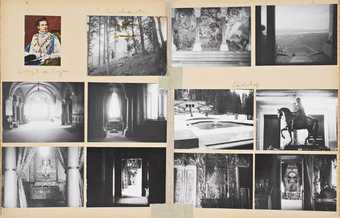

Kiefer’s interest in the ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV was matched by his fascination for ‘Mad King’ Ludwig II of Bavaria, who was a fervent devotee of both Louis XIV and the composer Wagner. They are referred to, or alluded to, textually and visually in the books Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet. Ludwig II constructed Herrenchiemsee Castle in emulation of his hero Louis XIV’s Palace of Versailles, although only fifty of the seventy rooms of the palace were ever completed; it was therefore a hollow imitation of the French original. In including Ludwig II in a book that investigates the psychology of National Socialism, Kiefer draws some parallels between the fantasies of Hitler, who loved Bavaria, and the fantasies of the Bavarian king. The latter tried to exceed the dimensions of Versailles’s Hall of Mirrors in Herrenchiemsee, but in many ways Ludwig II was living in his own hall of mirrors. He dreamed of absolutism and the divine right of kings, but was himself disempowered after the Bavarian state sided with Austria against Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War (1866), and he ultimately lost Bavaria’s status as an independent kingdom. Furthermore, the extraordinary cost of constructing his fairy-tale castles combined with his reclusive and erratic behaviour led to his ministers seeking to depose him by any constitutional means. He was declared insane in 1886 and transported to Berg Castle on the shores of Lake Starnberg where he died under mysterious circumstances. Ludwig II lived in a world of Wagnerian fantasy and all his castles referenced the operas of the Romantic composer; he ordered the creation of artificial grottoes and follies like elaborate stage sets for a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk.

Fig.8

Anselm Kiefer

For Jean Genet (Für Jean Genet) 1969 (pp.18–19)

Illustrated twenty-four-page book with bound watercolour on paper, graphite,

original photographs, hair and canvas strips on cardboard

665 x 510 x 40 mm

Hall Collection

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Tom Powel

In the For Jean Genet book Kiefer, whose own works occasionally have the appearance of Wagnerian stage sets, makes reference both to Wagner in inscriptions and to Ludwig’s castles in a sequence of out-of-focus photographs captioned in the artist’s handwriting ‘Königsschlösser in Oberbayern’ (in English ‘Royal Castles in Upper Bavaria’; fig.8). The emptiness of the photographed castle interiors suggests the isolation of the king alone in his throne room with his self-delusions of absolute rule. The sense of solitude and the remote location of these castles additionally bring to mind Hitler’s Berghof residence in the Bavarian Alps near Berchtesgarden, where Hitler envisioned his military conquests and occupations, as well as the even more remote retreat Kehlsteinhaus (known as the Eagle’s Nest), on the rocky mountaintop some distance above the Berghof. One of Kiefer’s photographs in the Heroic Symbols book is of the equestrian stature of Louis XIV in Ludwig II’s Linderhof Palace, a copy of a statue in the Place Vendôme in Paris, but it also recalls the other equestrian statue in Montpellier in front of which Kiefer gave the Hitlergruβ, which appears both in the Occupations performance and the wider Heroic Symbols photographic project. Romanticism, Absolutism and National Socialism are all thereby conflated in an unnerving manner that invites reflection on how the Third Reich developed in the mind of its despotic leader.

Here Kiefer seems to be expressing a wider concern with the function of aesthetics in the exercise of state power. He reflects on the psychological condition of the fantasist ruler, who seeks to harness heroic symbols of past glories – which with regard to Ludwig II and Hitler meant primarily Germanic myths and legends, and during the Third Reich also the development of monumental, paired down adaptations of classical imperial architecture – in order to galvanise their own present authority and to signal future ambition. Mussolini did something very similar in Rome, tapping into symbols of the Augustan age and developing the stripped classicism of the EUR (Esposizione Universale Roma), an architectural style that also found adherents in the Soviet Union during Stalin’s regime. Ludwig II and Hitler shared a love not only of Wagner’s visually evocative dramas and his concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (a total synthesis of the arts),8 but also a sense of architectural theatre, imposing grandiose visions through masonry and mortar, as well as epic son-et-lumière shows with their immense choreography, to excite and stimulate the masses to patriotic devotion and deeds. With Hitler, this aesthetic and political theatre was taken to another level through his much-practiced oratory and emphatic bodily gestures. Delusional over-the-top creativity and performance is a hallmark, Kiefer seems to suggest, of all rulers or ‘Dream Kings’, who pursue autocratic power and absolute authority, but with the devotional crowds absent from Kiefer’s photographs, and with no spectacular light shows in evidence, the focus is on the figure of an isolated megalomaniac, revealing a void at the centre of National Socialism and by extension other authoritarian regimes.

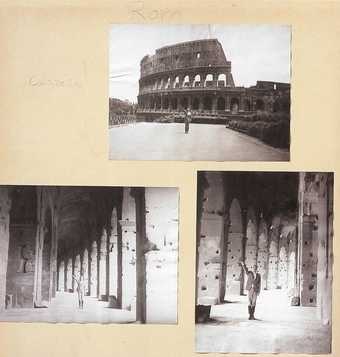

Fig.9

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969 (p.20)

© Anselm Kiefer

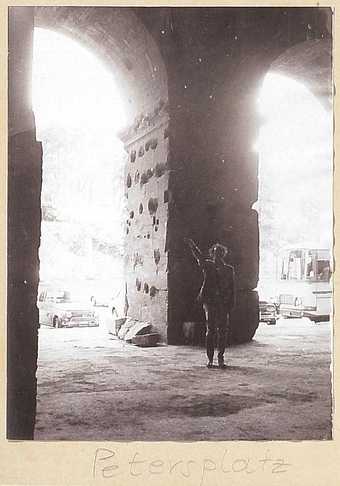

The potency of Kiefer’s photographs is that they usually trigger a mental slide show of other relevant images and thoughts. For instance, the photographs taken of the artist giving the Sieg Heil in the ruined grandeur of the Colosseum that Kiefer included in the Heroic Symbols book (fig.9) recall the connection between the Nazi salute and the old Roman ‘Ave’ salute. This link is strengthened when considered in light of the Italian Fascists’ adoption of the gesture prior to Hitler, a salute seen in archival footage of Mussolini on parade down the Via dell’Impero that connected the Colosseum to the Victor Emanuel II monument. In May 1938 the Via dell’Impero, which had been constructed to Mussolini’s instructions and involved the systematic demolition of mainly medieval and Renaissance structures in order to more clearly establish associations between the glories of the Augustan empire and Mussolini’s Rome, was redecorated with swastikas and eagles in readiness for the arrival of Hitler. This connection between the two Fascist nations, signified by Kiefer’s Nazi salute in Rome, also triggers thoughts of Charlie Chaplin’s film The Great Dictator (1940) and the ‘dance’ performed by Mussolini (Benzino Napaloni) and Hitler (Adenoid Hynkel) when they fail to shake hands as they try to out-salute each other. In addition to the secular Colosseum, in the Heroic Symbols books Kiefer also includes photographs of himself saluting under the colonnade of St Peter’s Basilica (fig.10), a photograph which could be related to his painting Heroic Symbol VIII 1970 in that both works suggest the tacit complicity of Pope Pius XII and many others in the Catholic Church in failing to challenge Nazism by maintaining neutrality.9

Fig.10

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969 (p.21)

© Anselm Kiefer

A Jewish context to Kiefer’s photographs of Rome can also be identified. In ancient Rome Jews were put to work as slaves for the construction of the Colosseum (72–80 AD), and nearby the Arch of Titus was erected around 81 AD by the emperor Domitian to honour the victories of his father Vespasian and his brother Titus in the war against Judaea, which put an end to the Jewish state for nearly two millennia. One panel of the Arch of Titus shows Roman soldiers carrying the spoils of war, including a huge gold menorah plundered from the Hebrew temple in Jerusalem. The arch and Colosseum thereby became symbols of Jewish defeat, places the Jews of Rome avoided for centuries until 14 May 1948, three years after the end of the Second World War, when a State of Israel was founded and the Jewish people converged en masse at the Arch of Titus to celebrate. Kiefer saluting pathetically alone in front of the Colosseum therefore suggests both the failure of Romans and National Socialists to subjugate and destroy the Jewish race and also signals the delusional nature of both Mussolini and Hitler in attempting to summon the glories of ancient Rome to bolster their own regimes. Grass has since grown over such imperialist ambitions, but in many ways the relevance of Kiefer’s work today is that it reminds us of the threat of neo-fascism, something insidious that continues to plague Europe especially in times of economic hardship.

Related early book projects and Kiefer’s first exhibition

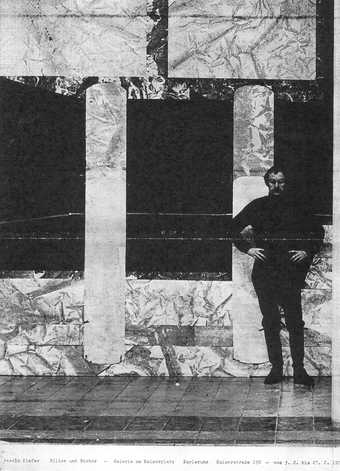

Fig.11

Flyer for Anselm Kiefer’s first exhibition Pictures and Books (Bilder und Bücher), Galerie am Kaiserplatz, Karlsruhe, February 1970

It is often incorrectly stated in the extensive literature on Kiefer that his first solo exhibition took place in 1969 at Galerie am Kaiserplatz in Karlsruhe, a space run by the painter Helmut Rehme.10 His first solo exhibition, which was simply entitled Pictures and Books (in German Bilder und Bücher), in fact took place at Galerie am Kaiserplatz in February 1970 (fig.11). According to the art historian and curator Eckhart Gillen, who was the first critic to write a review of Kiefer’s work, the exhibition did include the following book projects from 1969: The Heaven (Die Himmel), You are a Painter (Du bist Maler), The Flooding of Heidelberg (Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs) and The Source of the Danube (Die Donauquelle). However, it did not include the Occupations/Heroic Symbols photographs, books or the related paintings that were later were to cause such a sensation.11 While these other book projects did not include photographs of Kiefer giving the Sieg Heil salute, they did include other visual material revealing the artist’s engagement with symbols of the National Socialist past, and similarly explored associations between the notion of the artist-creator and totalitarianism.

For instance, You are a Painter plays on and subverts the idea of a loner with aspirations of world domination by including deliberately amateurish photographs of war games, without any human presence, staged with tin soldiers on a basic table with a white surface, photographs that also provide glimpses of mundane furniture and other objects, all in Kiefer’s home-studio. The strangeness of these monochromatic scenes is only heightened by the messiness of the artist’s live-work space and the unusual perspective of many of the grainy out-of-focus photographs where toy soldiers appear like a depleted army of insects crawling over giant sugar cubes (fig.12), and similar photographs also appear in For Jean Genet.

Fig.12

Anselm Kiefer

You are a Painter (Du bist Maler) 1969

220-page book with black and white photographs, ink on paper

250 x 190 x 10 mm

Private collection

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

Fig.13

Anselm Kiefer

You are a Painter (Du bist Maler) 1969 (cover)

Private collection

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Charles Duprat

The front cover of You are a Painter (fig.13) includes a photograph taken from a 1939 issue of the magazine Die Kunst im Dritten Reich showing a sculptural representation of the Northern Renaissance master Matthias Grünewald as an artist-seer, a work by Josef Thorak, which had been installed in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich for the Groβen Deutschen Kunstausstellung in the same year. Thorak, along with Arno Breker, was a high profile sculptor of Hitler’s regime, and in this work he celebrates Grünewald, who along with Caspar David Friedrich and others had been co-opted (or as Kiefer says ‘misused’12 ) by the Nazis as an archetypal German artist. Kiefer wrote his inscription ‘Du bist Maler’ in the sightline of the artist-seer, who is shown striking a heroic pose, head tilted upward and right hand over his heart gripping a tool of his trade. The words are entreating, but art historian Toni Stooss has perhaps misinterpreted the inscription in suggesting that the ‘title sounds like the twenty-four-year-old Kiefer’s insistent plea for reassurance’.13 Rather, given the contents of the book it seems much more like Kiefer’s imagining or ventriloquising of Hitler exhorting himself to accept his own artistic ability after his rejection by the arts establishment. This rejection must have in part led to his egotistic desire to impose his ‘creative’ vision on the world in more extreme ways with his grand designs for a thousand-year Reich. The psychology behind this ambition is what Kiefer explores in these books, along with the need to expose and satirise the ideology as absurd. The work manages to subvert the narcissistic sense of self-importance that so often defines the character of totalitarian rulers, but also prompts reflection, as the historian Kym Lanzetta has pointed out, ‘on the responsibility of the artist in heralding political despots, and the ways in which painters/cultural heroes are recruited and instrumentalised in patriotic, nationalist causes’.14

This lampooning of the delusional tendencies of totalitarian rulers can also be seen in Kiefer’s use of tin soldiers in The Flooding of Heidelberg 1969, where they are interspersed with more Nazi magazine photographs of National Socialist sculpture and buildings such as Albert Speer’s New Reich Chancellery in Berlin and Paul Ludwig Troost’s House of German Art in Munich, as well their appearance in the books Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet. This utilisation and mobilisation of toy soldiers is significant when one considers some of the photographs and watercolours of Kiefer giving the Sieg Heil in the Heroic Symbols book. The lampooning of megalomania also continues in Kiefer’s later book projects of the 1970s such as Operation Sea Lion (Unternehmen ‘Seelöwe’) 1975, the title of which is derived from the code name for Hitler’s delusional scheme to invade Britain by sea during the Second World War, in spite of Germany’s naval inferiority. This was a scheme that Kiefer re-enacted through photographs of toy battleships floating in an old zinc bathtub, the same tub that he employed for his Walking on Water photograph used in the Heroic Symbols books in which Kiefer appears to perform the Nazi salute while walking over the surface of the water that fills the tub. The eerie lack of human presence in the photographs reinforces the idea that these are the hidden quarters of a megalomaniac.

Heroic Symbols / Heroic Emblems: Anselm Kiefer and Ian Hamilton Finlay

The ironic strategies of Kiefer’s Occupations performance find a surprising corollary in the work of the Scottish artist and poet Ian Hamilton Finlay, particularly with Finlay’s 1977 book project of his graphic work titled Heroic Emblems. This could be another way of translating Kiefer’s German title Heroische Sinnbilder, as Sinnbild can mean ‘emblem’ or ‘allegory’ as well as ‘symbol’. Literary theorist and historian Tyrus Miller has identified the connection between Kiefer and Finlay and argues that ‘it would not be beyond Finlay’s historical knowledge and interests to have unearthed the very article on Nazi-Kunst that Kiefer references in his title’.15 Finlay could well have seen Kiefer’s 1975 photo-essay ‘Occupations’ (‘Besetzungen’) in the German conceptual art magazine Interfunktionen, in which eighteen of the Heroic Symbols photographs were published. However, it is not known where he might have seen Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols books because according to the gallerist Heiner Bastian they were not shown in public until the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Bilder und Bucher at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1978, the year after Finlay’s Heroic Emblems was published.16

![Ian Hamilton Finlay Propaganda for the Wood Elves [collaboration with Harvey Dwight] 1981](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig14ianhamiltonfinlaypropagandaforthewoodelve.width-340.jpg)

Fig.14

Ian Hamilton Finlay

Propaganda for the Wood Elves [collaboration with Harvey Dwight] 1981 Tate

Miller suggests that in Finlay’s graphic work and in his inscribed plaques and sculptures in his garden Little Sparta, the artist is more overt than Kiefer in his treatment of National Socialism, and Miller illustrates this point with a graphic work from Heroic Emblems that shows a Nazi Panzer tank ‘poking its turret through the underbrush and bearing Poussin’s famous Arcadian inscription, Et In Arcadia Ego’.17 However, it remains moot whether Finlay addresses the subject more overtly than Kiefer and it is worth noting that in 1977 Kiefer created a work entitled Baum mit Panzer (Tree with Panzer Tank; private collection) in which the tanks in the composition create a major disturbance in one of the key symbols of German identity, the forest. On the theme of the arboreal, Tate owns a photograph by Finlay titled Propaganda for the Wood Elves [collaboration with Harvey Dwight] of 1981 (Tate P07926), which shows a tree in Little Sparta with an axe resting against it and a swastika wrapped around the upper part of its trunk (fig.14). According to Tate’s catalogue entry for the work, ‘the artist described the images as “an enigmatic emblem. Visual paradox is one mode of an emblem”, adding that it referred to German tree-worship and the violence of nature’.18 This is not at all dissimilar to Kiefer’s 1970s exploration of the associations between Romanticism, arborealism and National Socialism,19 and like Kiefer, Finlay was also accused by some critics of having an unhealthy fascination with Nazi iconography.

Finlay also shared Kiefer’s proclivity for imaginatively blurring invented and actual history and topographies. That Finlay was very aware of Kiefer’s work from the 1970s onwards is also borne out by other examples. Finlay’s exhibition The Third Reich Revisited, which was shown at the Tartar Gallery during the 1982 Edinburgh Festival, juxtaposed with satirical intent Edinburgh neoclassicism and Speer-style architecture, especially in showing a drawing of a ‘massive neoclassical rectangular façade crowned with a huge Nazi-style eagle … identified as “St Andrew’s House, Edinburgh”’.20 This work may have owed something to Kiefer’s various visual investigations of the architecture of Speer, especially those focusing on the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin that Kiefer created between 1980 and 1981. The connection between Kiefer and Finlay was finally made explicit a decade later when Finlay created a card titled Women of the Revolution after Anselm Kiefer 1992 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), which he made around the time of the installation of Kiefer’s Women of the Revolution 1992 (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco) at the Anthony d’Offay gallery in London. In this card, Finlay assigned to different plants the names of famous French women involved in the French Revolution, whereas in Kiefer’s installation their names were allocated to beds made of lead. While there are points of contact between Kiefer and Finlay, however, it is arguable that the German artist’s work is much more complex in deconstructing cultural history: while they both investigate Nazi iconography, Kiefer often simultaneously memorialises the Holocaust and shows how the ideological spectrum of Romantic nationalism can have devastating consequences.