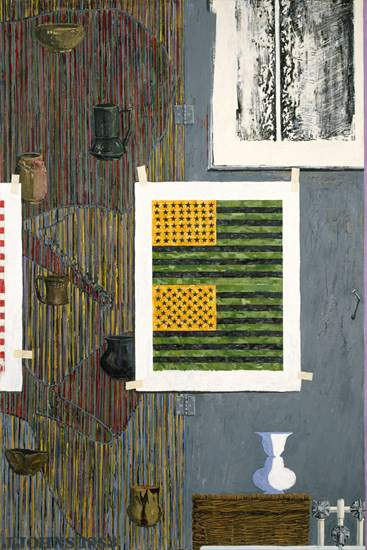

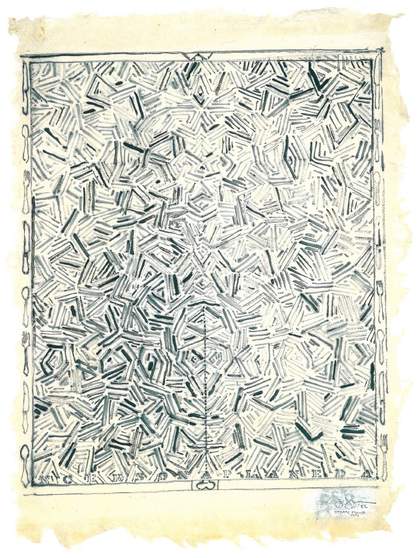

Fig.1

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane 1980–1

Oil paint and acrylic paint on canvas and bronze frame

Support: 2000 x 1619 mm

Frame: 2002 x 1620 x 58 mm

Tate T03242

Artwork © Jasper Johns

Photo © Tate

Jasper Johns’s Dancers on a Plane 1980–1 (Tate T03242; fig.1) is a large oil painting incorporating stencilled text surrounded by an artist-made bronze frame that is itself covered with oil paint. The picture belongs to the body of ‘crosshatch’ works created by Johns between c.1972 and 1982. These works are comprised of bundles of roughly parallel lines – ‘slanted lines on the diagonal, a sort of cross-hatching’, as Johns put it – that are spread in various directions across the entire surface of each work’s composition.1

In Dancers on a Plane an imagined vertical line divides the painting into two loosely mirrored halves, each of which is then divided horizontally into four parts. The hatches that are spread across them, rendered in dark blue, lilac, green and orange, generally change in direction at the first and third divisions from the top, and they shift in colour at the second division from the top. Johns has placed the name of his long-time associate, the dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham, across the painting’s bottom edge in black letters, beginning at the canvas’s centre. Alternating with those black characters are the reversed letters of the painting’s title, starting near the left-hand edge of the painting and stencilled in colours echoing those deployed in the hatchings above. A dotted line charted in black and white begins at the centre of the painting’s lower edge and extends halfway up the canvas. This helps direct attention to the work’s decorated frame, and particularly to its bottom centre, where Johns has placed a pair of testicles, formed by the removal of an ovoid-like shape from an appended bronze rectangle, itself scored with lines suggesting pubic hair. Vertically opposite these testicles, at the top centre of the frame, is the suggestion of a phallus, indicated by two short parallel lines positioned between a pair of bronze triangles adjoined to one another, which resemble a vagina in the act of being penetrated. Cast spoons, forks and knives are embedded within the frame’s left and right edges, following a pattern of knife-spoon-fork from the upper left downwards and knife-fork-spoon from the upper right downwards.

Dancers on a Plane was acquired by Tate directly from the artist’s studio in 1981, the same year that it was completed. At this point Johns’s reputation as an important artist was secure and this work was a welcome addition to the museum’s collection, representing an example of the artist’s most recent practice as well as complementing an earlier painting acquired by Tate in 1961, 0 through 9 1961 (Tate T00454).2 Dancers on a Plane could also be understood in relation to Johns’s ongoing printmaking enterprise, a major feature of his artistic practice since 1960 and one showcased by the 1981 exhibition Jasper Johns: Working Proofs, on view at the Tate Gallery around the time of the painting’s acquisition. Not only was the hatch itself integral to the building of volume within printmaking traditions, but the use of mirroring in Dancers on a Plane, as in other crosshatch works by Johns, also seems connected to the printmaking process’s reversal of an image as it is transferred to paper.

Dancers on a Plane is one of a group of works made by Johns that bear the same title, as will be outlined later in this essay. The first, executed in 1979, is a painting that shares its dimensions with the Tate picture, while later iterations include smaller works in paint or graphite. All of these employ the hatching technique, and all were made during the final years in which Johns used hatchings and around the time of his 1982 turn to a fresh range of motifs in his painted work.

In more than one sense the 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane signalled one of several key turning points in Johns’s long career, having been created around a moment seemingly shot through with changes and thoughts of change. As well as being among the last works to make exclusive use of the hatching pattern, it is notable that it was begun in 1980, the same year that Johns’s thirteen-year stint as artistic advisor to the Merce Cunningham Dance Company officially came to an end. In addition, earlier changes of course in the artist’s career were brought into view by two major shows of Johns’s work staged in New York around this time – a travelling retrospective originating at the Whitney Museum of American Art in late 1977, and a large-scale exhibition of nearly all of the artist’s drawings from the 1970s at the Leo Castelli Gallery in early 1981. One might imagine the experience of those events opening onto still another shift for Johns, altering his perspective on his work to date. The steady emergence and entrenchment of new artists and artistic trends – from minimalism to process art to conceptualism – over the course of the 1970s may well have had a similar effect. The artist even spoke about the 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane in terms of a variation in mood: after completing his first Dancers on a Plane in 1979, he considered how he could go on from that painting in another work, stating that he ‘started thinking of the same information in a different order – or tone of voice – or emphasis … But by the time I got around to it, I wasn’t in that mood’.3

The many shifts surrounding Johns’s practice around 1980 will be taken up and brought to the fore in different ways throughout this In Focus project. This first section suggests that a thematic of change crucially underpins Johns’s work on the 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane. In ‘The Hatchings: Technique as Motif’ art historian Seth McCormick considers the transitions that informed the many years of Johns’s engagement with hatching and the ways in which Dancers on a Plane frames this period of the artist’s production. ‘Johns and Cunningham: Dancing on a Plane’ explores the artist’s relationship with the dancer-choreographer as well as the significance of Johns’s move away from work with the Cunningham Dance Company, while ‘Incarnating Duality: Jasper Johns and Tantric Art’ considers the influence of Tantric art and its imagery on Dancers on a Plane.

Turning points: The painting and its frame

When Johns executed Dancers on a Plane he had already been working with the hatching motif for nearly a decade. The artist has located the origin of his hatches in markings he once saw on a passing car – ‘I only saw it for a moment – then it was gone – just a brief glimpse. But I immediately thought that I would use it for my next painting’.4 Yet, as is frequently observed, the motif also taps into the history of art, from techniques of the graphic tradition, to the hatching of Pablo Picasso as he moved towards cubism in the early twentieth century, to the all-over compositions of the abstract expressionists from the 1940s onwards. After debuting the hatching motif in his Untitled 1972 (Museum Ludwig, Cologne), where it covers the leftmost of that work’s four panels, the marks became the sole pictorial event in Johns’s 1973–4 painting Scent (Collection Ludwig, Aachen).5 The crosshatch paintings were then first displayed as a body of work in 1976 at the New York gallery of Johns’s long-time dealer Leo Castelli.

That show – the artist’s first solo exhibition of paintings in eight years – featured seven carefully selected paintings ranging in size from 870 x 1378 mm (The Barber’s Tree 1975, Collection Ludwig, Aachen) to 1829 x 3206 mm (Scent). While critic Jeff Perrone may have been right in 1978 when he claimed of the crosshatch works, ‘I don’t think anyone was prepared for this unforeseen change in Johns’s art’ – in their apparent abstraction they could seem a departure from his earlier work with ‘things the mind already knows’ – the exhibition at Castelli’s gallery was largely well received, and critics quickly worked to come to terms with the artist’s new idiom.6 They sought to elucidate the various complex organising systems that informed Johns’s hatchings; however, they were also keenly attuned to the fact that a crosshatch painting was not ‘a mere instance of some system’s application’.7 Joseph Masheck, for instance, emphasised that ‘the exact workings of the system are hidden from view, submerged in a rich texture of strokes’ while Thomas Hess claimed that the initial effect of the 1976 exhibition was a ‘slippery, eliding, dizzying sensation’ but that after ‘studying the paintings for a while, you begin to sense that strong ordering forces underlie the skin of chaos’.8

Moreover, Johns’s use of a predetermined scaffold for his painting also ultimately, and crucially, connected the crosshatch works to his earlier output. Flags, targets, maps, numbers and alphabets were all replaced, as curator and art historian Mark Rosenthal, among others, has pointed out, by systems of Johns’s own devising while his paint handling continued to be perceived as a work’s main attraction.9 Such continuities may have become even more apparent when the crosshatch paintings were installed with Johns’s earlier works at his Whitney retrospective in 1977: although the exhibition featured a total of 165 paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures from throughout his career, we know that it nevertheless confirmed the artist’s sense that his work was ‘too much of a piece’.10

Fig.2

Jasper Johns

Ventriloquist 1983

Encaustic on canvas

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

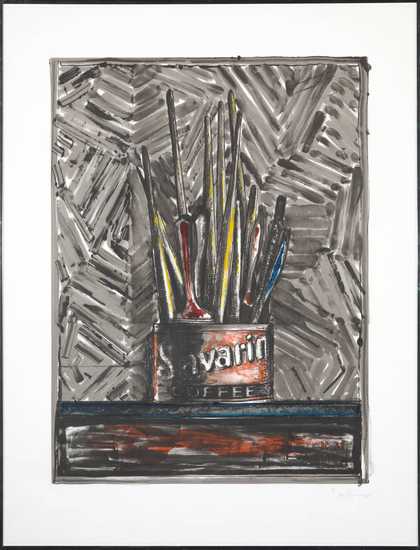

Fig.3

Jasper Johns

Savarin 1982

Tate P07736

Artwork © Jasper Johns

Photo © Tate

By the time of Johns’s 1981 completion of the Tate Dancers on a Plane, his work was again on the precipice of a major change, perhaps a response to what the artist observed in his retrospective. Deemed a surprise by many, a solo show of his new painting at Castelli’s gallery in 1984 brought together nine crosshatch paintings, the earliest dated 1978 and including the Tate picture, with five paintings from 1982 and after, this latter body of work variously incorporating trompe l’oeil illusionism, references to the history of art and seemingly autobiographical motifs. Uncharacteristically in these works Johns appeared to ‘drop the reserve’, as he put it, and reveal something of himself.11 A work like Ventriloquist of 1983 (fig.2), for example, saw the transformation of the picture plane into a bathroom wall, on which hangs a representation of a 1961 Barnett Newman lithograph, a Johns double flag painting and another fragment of flag all pinned up by trompe l’oeil tape, a nod, perhaps, to the illusionistically rendered nails that at times appear in Georges Braque’s analytic cubism (see, for instance, Violin and Palette of 1909, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York). Yet if this exhibition seemed, on the one hand, to announce a decisive break with the abstraction of the crosshatches, on the other it might be perceived as mapping out Johns’s transition to his new mode of working – a view also held by critics at the time and expanded on since.12 Already with the poster he designed for his Whitney retrospective five years earlier, the artist had advertised the possibility of the hatching motif opening back onto an engagement with recognisable images (a lithograph of the image used for the poster is owned by Tate; fig.3). The poster used the hatching motif as a background for a representational image of a Savarin coffee can filled with paint brushes – familiar from his 1960 sculpture Painted Bronze (promised gift to the Museum of Modern Art, New York). The image not only yoked together references to the artist’s past and present works but also gestured toward his future production.

The Tate picture, however, is less a work of transition – one that links before and after, that takes steps in a new direction – than a work about transition: the notion of the shift itself is the work’s central conceit. It is as though Dancers on a Plane gathers up all of the many revisions of course that constellated around its moment of creation and makes the facts of them its subject, metaphorising them in various ways. Here we might think again not only of nascent developments within Johns’s painterly practice but also of his official retirement from the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, his recent exhibitions, the increasingly fast-paced evolution of the art world, and even the further solidification of Johns’s blue-chip status following the 1980 sale of his Three Flags 1958 to the Whitney Museum of American Art for one million US dollars (at the time, the most ever paid for a work by a living American artist). Dancers on a Plane ultimately stands as a taking stock of and meditation on such changes in direction, an evaluation of the possibilities and limitations they present.

The workings of the painting itself bear this out. Dancers on a Plane is perhaps first and foremost defined by an overall density. Immediately striking is the sheer number of tightly interwoven bundled lines that the work contains, a quantity made possible by the relatively compact nature of each cluster – these are not the comparatively broad sweeping hatches of, say, the contemporaneous Between the Clock and the Bed pictures (see, for instance, Between the Clock and the Bed 1981, Museum of Modern Art, New York). Ridges of paint characterise the brushstrokes throughout, and the complexity of the work’s overall topography directs further attention to the individual markings. As short, emphatic strokes move this way and then that, an insistence on their ever-shifting nature quickly comes to seem central to the painting’s operations. The work’s disposition of colours quite literally highlights these manifold variations in direction: for example, as yellow hatches in the two uppermost right-hand sections of the painting stand out against their cooler neighbours, they offer a mini-survey of different possible orientations. The use of secondary or otherwise blended colours then thematises change in still another way. In the hatch marks we also sense the continuous, almost staccato shifting of Johns’s hand – their diagonal arrangement signalling handedness, as art historian Jennifer Roberts has pointed out, as the hand itself is perhaps analogised by the hatches – and with it his body, his physical movements underscoring the importance of transition to the act of creating the painting.13 The hatches’ – and Johns’s – gamut of movements is complemented by shifts in pace across the canvas: while many clusters of strokes slow as they thicken, such as the bright orange marks just left of centre, elsewhere the tempo quickens. This can be seen, for example, in the painting’s smoother, more fluid strokes and in those with a higher sheen, many of which congregate in the upper registers of the painting, as well as in passages where we see paint that has dripped.

Importantly, the activity on the canvas is not left to stand alone but is instead encompassed by the artist’s frame. Frames in general are fairly unusual within Johns’s oeuvre. Indeed, it was the absence of a frame that helped give rise to the play between object and image, or presentation and representation, that underwrote art historian and curator Alan Solomon’s renowned 1964 discussion of the artist’s work.14 Moreover, the frame surrounding Dancers on a Plane is especially distinctive for its complexity and its incorporation of objects, the latter not uncommon within Johns’s work in general yet all but absent from his crosshatch paintings.

Frames may well have been very much on Johns’s mind as he made Dancers on a Plane. His recent Whitney retrospective had offered a particular framing of his career and spurred on the articulation of countless others in the art press and beyond. The exhibition and surrounding events also put Johns himself in a position to reconsider his career to date and its many changes of course as well as his evolving relationship to an always-changing art world and its larger movements and frameworks.15 To begin with the latter point, the bronze forks, knives and spoons could be associated with minimalism’s industrial forms, while their straightforward, regular arrangement also easily brings to mind the turn away from composition signalled by minimalist artist Donald Judd’s phrase ‘one thing after another’, as well as by conceptualist Mel Bochner’s sense that ‘the order takes precedence over the execution’.16 At the same time, Johns complicated his connection to those movements. The uneven distribution of paint covering the frame of Dancers on a Plane suggests an irruption of the artist’s hand that distances his work from the uninflected surfaces and seriality of minimalism, as from the conceptualist prioritisation of system. Similarly, the pattern followed by the cutlery might be read as a nod towards the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s with which Johns’s crosshatchings had at times been critically associated, and which focused on opulent decoration as an alternative to a cooler minimalism and conceptualism. Yet by lodging his work’s clearest pattern in objects as well as in its frame, both entities often pointedly absent from Pattern and Decoration works, it is as if Johns was deliberately highlighting his difference from that group. Indeed, Johns’s frame seems designed in part to announce his work’s status as other than ‘mere’ decoration – a reading of their art that dogged the Pattern and Decoration painters – and instead as undoubtedly belonging to the realm of painting proper.17

The cutlery fixed in place on the vertical edges recalls a classical frieze, or, given the allusion to movement in the Tate painting’s title – and the clearly defined movement of lines across its surface – perhaps even a freeze-frame. On the one hand, this seems to offer an overture to performance art and one mode of its transmission, namely single static images recorded by a camera. On the other, it alludes to the tension between motion and stoppage that is also played out in the optical vibration of lines in contrast to the heavy oil paint application. The body does make an appearance within the frame, at once seemingly creeping into and central to it, in the form of the phallus and testicles on its upper and lower edges. While the almost cartoonish quality of both, especially the testicles, can bring to mind the contemporaneous work of the painter Philip Guston, these elements also seem both related to the erotic bent of a burgeoning neo-expressionism – seen, for instance, in the early work of Eric Fischl – and reminders of Johns’s own remove from that mode of painting.18

The frame also recalled a range of Johns’s own earlier work. His use of cutlery was not new: actual spoons and forks appear hanging from the surface of paintings such as In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara 1961 (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago) and Voice 1964/1967 (Menil Collection, Houston). Similarly, the frame’s testes seem an echo of Johns’s 1960 Painting with Two Balls (collection of the artist), a work with a pair of wooden spheres inserted between vertically adjacent canvases, offering a tongue-in-cheek allusion to the machismo of abstract expressionist painting: in reasserting control over how his work was positioned relative to others, it is as if he saw himself now framing with two balls. The use of painted bronze for the frame in Dancers on a Plane itself appears a subtle reprise of Johns’s landmark 1960 sculptures, each named Painted Bronze, which included his pair of Ballantine Ale cans (Painted Bronze 1960, Museum Ludwig, Cologne) and the previously mentioned Savarin coffee can stuffed full of paint brushes.

Curator Kirk Varnedoe has observed that this sort of recycling, common in Johns’s work, embodies the artist’s concern with the unrepeatable, one that opened onto his efforts to make over his past in a manner adequate to his present.19 The frame of Dancers on a Plane makes a related point: it shows us that the context of Johns’s work is often its own history; it casts the idea of recurrence with difference as a central thematic, or as the essential framework for understandings of this painting. As will be argued below, this thematic also underlies the Dancers on a Plane works as a series.

The series: A company of dancers

In 1980 Hans Namuth photographed Jasper Johns at work on Dancers on a Plane in his studio in Stony Point, New York. With the painting on a wall, Johns crouches before it, stencil and paintbrush in hand. On the adjacent wall, slightly behind the artist and to his left, hangs his 1979 Dancers on a Plane (collection of the artist), the first painting to bear that name. The two works, which share a title, size and, loosely, a pattern, appear as if pendants, and to this duo Johns would in 1981 begin adding more works with the title Dancers on a Plane – a further two paintings (made in 1980–1 and 1982) and a drawing (also 1982).20 It was hardly unusual for Johns to return to a motif in this way: witness the recurrence in his work of targets, numbers, flags and even the hatching technique itself. In 1978, the year before he painted his first Dancers on a Plane, the artist remarked that ‘one of the most interesting things one can do is use something in a variety of adaptations, and then ask the question “what does it mean?”’.21 In the context of his Dancers on a Plane works more widely, the meaning of his various adaptations turned out to be bound up with thoughts of parts, wholes and the relations among them, all ideas long central to the artist’s practice. Understanding these works as a group – their similarities, idiosyncrasies and interrelations – will help to bring the Tate Dancers on a Plane into sharper focus.

Fig.4

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane 1979

Oil paint on canvas with objects

1978 x 1626 mm

Collection of the artist

© Jasper Johns

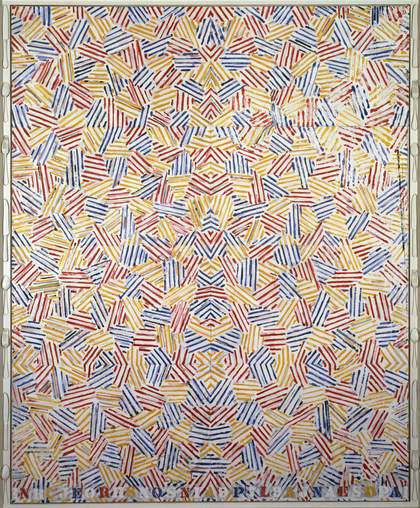

We might begin with an eye to the first Dancers on a Plane, made in 1979 and still in the artist’s collection (fig.4). According to art historian Michael Crichton, Johns said that while making it he was

thinking about issues like life and death, whether I could even survive. I was in a very gloomy mood at the time I did the picture, and I tried to make it in a stoic or heroic mood. The picture is almost uninflected in its symmetry. There is no real freedom. The picture had to be executed in a very strict fashion or it would have lost its meaning.22

There is something claustrophobic about the work, the air sucked out by its white paint, with the familiar Johnsian palette of densely applied primary colours appearing as a further restriction of freedom. Each discrete bundle of marks looks as if it is locked in place by its often sharply ridged neighbour. The decisive manner in which the multitude of hatches appear to have been laid down further testifies to the fact that the work is ‘not involved in impulse’, as Johns claimed of it.23 Indeed, the artist once remarked that he ‘began to think of a dancer on a stage’ as he made the painting, and his actions, too, seem rehearsed.24

Such an approach also entailed a careful engagement with the relation between part and whole. The 1979 Dancers on a Plane is divided vertically into two mirrored halves and horizontally into four sections; as the hatch marks cross the borders of those latter sections they change first direction (at the lowest border), then colour, then both direction and colour. While nearly all the crosshatch paintings are similarly organised around such divisions, the constitutive segments of the first Dancers on a Plane are rendered especially definite by the relative crispness of the painting’s execution.25 Johns’s central placement of the letter ‘A’ at the canvas’s lower edge – although surely deposited there in part owing to its symmetry – might be read as directing further attention to the distinct sections comprising the work, its prominent position perhaps leading the beholder to consider how each is ‘A’ singular portion of the work. The atomised clusters of hatch marks and their puzzle-like coming together then redouble our sense of the painting as a whole built out of parts, as does the cutlery in the frame, itself a set made out of discrete components. ‘Such things run through my work, relationships of parts and wholes’, Johns remarked in 1978, adding that ‘It relates to so much of one’s life’.26 It is as though with the 1979 Dancers on a Plane Johns metaphorically tested out the possibility that his painting could be strictly understood as the sum of its parts, a test that would have undoubtedly at once proved restricting and provided a blueprint for how to continue. Significantly, however, the limits of this approach were already apparent in the 1979 painting: note, for example, the streak of black on the far right that overtly refuses to be contained by the painting’s scheme.

That stroke in many ways sets the tone (and palette) for the second Dancers on a Plane, the Tate work of 1980–1 (fig.1), painted with its predecessor quite literally in view as per Namuth’s photograph. The two paintings share a title, size, a frame containing cutlery and roughly the same gridded structure, yet beyond this their differences are quite pointed. To begin with, Johns said of their connection, ‘The second picture took the same information and was more playful’, and indeed the second work does seem more animated than the first.27 The density of hatch marks in any one area varies as does the character of each cluster, their relative buoyancy or heft shifting across the canvas. An irregular deployment of a greater range of colours likewise infuses the second work with a sense of kinetic energy, and the composition as a whole wriggles loose from the dictates of the implied mirror. Johns stated of this latter aspect of the second Dancers on a Plane that ‘the symmetry is less rigid, somewhat blurred’ as compared to the first painting. A similar blurring occurs around the later painting’s horizontal divisions: Johns deaccentuated but did not do away with the boundaries of its underlying grid.28 It is as though the composition’s parts are now understood as opening onto a fluid, evolving whole rather than a fairly static one: there is still room for manoeuvre. The Tate picture would appear dynamic under any circumstances, yet here the stakes of its dynamism as a sort of liberation, a reanimation and remobilisation of Johns’s project and its constituent parts, are set into relief by attention to its partner.

The two works’ common ground and their separation are apparent in other ways as well. Consider again how the Tate Dancers on a Plane deploys the mirroring device: its two sides are hewn closely enough to one another that their relation is clear, yet that proximity also makes any divergences all the more pronounced. Moreover, while the words ‘Dancers on a Plane’ are stencilled along the bottom edge of both canvases in capitals – the stencil itself a marker of uniformity – the proper names interspersed among the title change from ‘Jasper Johns’ in the 1979 work to ‘Merce Cunningham’ in the 1980–1 painting. This allusion to specific, finite bodies – reinforced by the human scale and bilateral symmetry of both paintings – is another nod towards the fundamental similarity and difference of the two works. Johns’s decision to mirror-reverse the title in the Tate picture further serves to short-circuit a sense of uniformity between it and its predecessor. Furthermore, something comparable is achieved by the prominent frames of these first two Dancers on a Plane works: on the one hand, they serve as barriers guaranteeing each painting’s distinction from the other, as emphasised by the frames’ different colouring, the first painted white, the second painted grey; on the other, the Tate picture’s frame summons thoughts of coupling through the testicles on its base as well as through the phallus apparently in the act of penetration on its top. Unsuccessful in attempts to incorporate these elements into his first Dancers on a Plane, Johns fittingly found a place for them in its partner.29

Fig.5

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane 1980–1

Oil paint on canvas

Private collection

© Jasper Johns

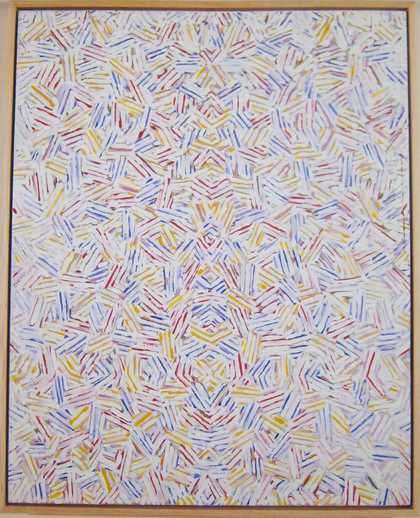

This second Dancers on a Plane turned out to be fertile, opening onto further paintings; as the artist and critic Marjorie Welish observed of the Tate work: ‘The painting reads “This is only one of many possibilities”’.30 Another Dancers on a Plane painting (fig.5), also made in 1980–1, resembles the Tate picture in palette and composition but is dwarfed by it, measuring a mere 406 x 508 mm; no frame is included and although the lettering at the bottom edge also features the name ‘Merce Cunningham’, the title is no longer mirror-reversed, Cunningham’s name is now in white and the letters are arrayed differently. At this point, it is worth re-emphasising that Johns reworked existing motifs in this manner throughout his career. It is equally important to add that this practice would have had an even broader resonance in the 1970s against the backdrop of minimalist and conceptualist engagements with seriality, as discussed above in relation to the cutlery on the Tate painting’s frame. In 1977 Johns indicated his awareness of this by saying, ‘Sometimes there are slight things I want to do in a slightly different way; I do one thing, the next thing will be done slightly differently. I suppose in fashionable terms you’d call the way I work a “set”.’31

Fig.6

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane 1982

Oil paint on canvas

406 x 508 mm

Private collection

© Jasper Johns

Yet the types of relationship established among Johns’s Dancers on a Planealso suggest another potential point of reference: dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham, to whom Johns gave the smaller 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane as a gift.32 When Johns began the Dancers on a Plane series he was engaged with Cunningham’s work in a professional capacity as artistic advisor for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, but he had been close with the dancer-choreographer since the 1950s.33 The partnership of the first two works might indeed bring to mind that of Cunningham and composer John Cage in their early and foundational joint dealings with rhythmic structure, a system they first used in the 1940s that allowed each man to compose independently with the understanding that during performance the dance and music would intersect at predetermined points. That the small dark painting given to Cunningham was followed in 1982 by an equally small Dancers on a Plane (fig.6) that shares the palette of the 1979 painting, thereby reiterating the relationship between the larger ones, further suggests that an ideal of partnership that valued at once connection and separation was at stake.

Yet given this steady proliferation of Dancers on a Plane paintings it seems that Johns was no longer strictly thinking in terms of partnership; he was also exploring relations within a larger group. This was likely informed by Cunningham’s later productions, and specifically the collaborations they involved. Starting in the 1950s, the choreography, music and set for Cunningham’s dances were created independently and came together for the first time only near the moment of performance: ‘three distinct components, no one dependent upon the other, but acting interdependently at the same time’, as Cunningham described the collaboration around his 1958 Summerspace.34 If the interdependence of Johns’s Dancers on a Plane paintings seems indisputable – common patterns, pairings, palettes – then equally apparent is their fundamental difference from one another.

Notions of company circulate throughout the Dancers on a Plane works. We might see in these paintings’ engagements with parts and wholes a connection to events in Johns’s life: perhaps to the interactions demanded by his 1977 retrospective at the Whitney as it thrust him into various ongoing dialogues with others, or to the context of the Gate Hill Cooperative in Stony Point where he often worked. However, the Dancers on a Plane paintings in particular seem to engage rather explicitly with two communities long central to Johns’s work. One is of course the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, evoked in ways already described. The other is that of the printmaking studio, central to Johns’s practice as an artist since 1960. As mentioned above, this is signalled by the paintings’ hatching, a technique used for building volume in graphic traditions; the stencilled letters; the mirroring that reflects a printmaker’s act of reversing an image as he or she transfers it to paper; the various iterations and permutations over time; and in the case of the first two Dancers on a Plane paintings, the way the frame’s cutlery surrounds the canvas, seemingly making a plate of it.35

Fig.7

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane 1982

Graphite on paper

889 x 686 mm

Kravis Collection, New York

© Jasper Johns

A 1982 drawing (fig.7), also bearing the name Dancers on a Plane, seems to consider how such communities come together. This work in graphite is necessarily devoid of any of the muddled paint strokes present in the other works discussed thus far. As such we get a strong impression of each hatch mark’s position in relation to the others, and, with that, a sense of the labour involved in placing each mark, which is to say the labour that stands behind successfully drawing parts together into a whole.36

Exhibiting the part and the whole

Since entering Tate’s collection, Johns’s painting has travelled to a range of different exhibitions. These have indicated many potential avenues of inquiry into the work, a number of which will be addressed in new ways in this In Focus project. The painting’s presence in the exhibition Jasper Johns: Work Since 1974, installed at both the Venice Biennale and Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1988, and in the artist’s 1996 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, suggests the importance of considering where the work sits in Johns’s own history, as well as in art history more broadly. Its inclusion in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s 2009 exhibition The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989 signals the rewards of carefully examining Johns’s engagement with Tantra, as Seth McCormick does elsewhere in this In Focus. Finally, the fact that both the Anthony d’Offay Gallery’s 1989 Dancers on a Plane: Cage, Cunningham, Johns and the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s more recent Dancing Around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp (2012) featured the Tate painting indicates the importance of carefully considering the connection between Johns and Cunningham.

Widening out to consider the series of Dancers on a Plane works, their movement through the world as objects can feel like an extension of their project. With one in the artist’s collection, one at Tate and three in private collections (one of which was owned by Cunningham until his death), they bring to the surface questions about what stays private and what is made public.37 At the same time, the overlaps in the works’ exhibition histories suggest that they beckon to one another: they are frequently installed together despite their clear self-sufficiency. Their coming together elucidates Johns’s remark that: ‘If the whole can become a detail we see the mutability of the world, and shifts of meaning or of image or definition follow’.38 In making details of the Dancers on a Plane by bringing them together, exhibitions offer new and diverse contexts that facilitate changing readings of them. Far from mutually exclusive, the approaches adumbrated by such exhibitions turn out to be mutually enriching, much like the Dancers on a Plane works themselves.