Merce is my favorite artist in any field. Sometimes I’m pleased by the complexity of a work I paint. By the fourth day I realize it’s simple. Nothing Merce does is simple. Everything has a fascinating richness and multiplicity of direction.

Jasper Johns, Newsweek, 27 May 19681

A photograph by James Klosty in his 1975 book Merce Cunningham shows what we could take to be a dancer’s leotard hanging from the upper left corner of one of Jasper Johns’s target paintings (fig.1).2 In many ways the photograph seems emblematic of the relationship between Johns and the dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham. It speaks of a routine intimacy: the slightly wrinkled leotard casually perched on and brushing against the unprotected painting, as if signalling the way their dance and painting variously came together without either one relinquishing autonomy. The only caption given for the photograph is ‘Jasper Johns’s studio’, but were a title needed, with the painting serving as the ground for the figure of an imagined dancer, then Dancer on a Plane might do.

Fig.1

James Klosty

Jasper Johns’s Studio, undated

Photograph

© James Klotsy

Fig.2

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane 1980–1

Tate T03242

Something of the relationship that Klosty’s photograph captures seems to lie at the heart of Johns’s own Dancers on a Plane 1980–1 (Tate T03242; fig.2), created roughly a quarter of a century after the painter first met the dancer-choreographer and around the end of Johns’s stint as artistic advisor to the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. During his tenure, which began in 1967, Johns designed sets and costumes for Cunningham productions and also enlisted other cutting-edge artists – from Frank Stella to Bruce Nauman to Andy Warhol – to do the same.

As is often noted, from the formation of his company in 1953 Cunningham left the visual artists with whom he collaborated to their own devices rather than insisting that their décor and his choreography engage with a single idea, which was the traditional approach for dance productions. By the time he began working for Cunningham in 1967 Johns would have been intimately familiar with this approach. Soon after meeting Cunningham, Johns had helped Robert Rauschenberg with the first set he made for the dancer-choreographer (Minutiae 1954).3 For the remainder of the 1950s Johns regularly assisted Rauschenberg in an unofficial capacity with his designs for Cunningham’s productions, perhaps a natural complement to the two men’s joint work around this time on the commercial design of department store window displays, which they created under the collective pseudonym ‘Matson Jones’. From the 1960s, Johns then worked to raise funds for and awareness of Cunningham’s dance through the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, which he established with the composer John Cage.4 Johns has stressed the significance of a period during which he, Cage, Cunningham and Rauschenberg ‘saw each other frequently and exchanged ideas’,5 reflecting that he deemed those three men ‘the essential people’.6

It has long been acknowledged that this group’s ongoing interactions with one another opened onto meaningful aesthetic affinities within their diverse practices. Already in 1968 the critic Calvin Tomkins had grouped Cage, Cunningham, Duchamp, Rauschenberg and the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely in his book The Bride and the Bachelors – although it is worth noting that the original 1965 edition omitted Cunningham – and in 1977 art historian and critic Moira Roth considered Cage, Cunningham, Duchamp, Johns and Rauschenberg in her frequently cited article ‘The Aesthetic of Indifference’.7 That there exist rich resonances among the work of Cage, Cunningham, Johns and Rauschenberg was also the premise, for instance, of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 2012 exhibition Dancing Around the Bride (which added Duchamp to the mix), as it had been for the Anthony d’Offay Gallery’s 1989 exhibition Dancers on a Plane (which excluded Rauschenberg) – both shows featuring the Tate Dancers on a Plane.8 Yet while the significance of Cage and Rauschenberg to Johns’s work has been considered in some detail, the importance of Cunningham has been less frequently explored. It is just such an exploration that the Tate painting demands and that will be offered here.9

The collaborative body

That Cunningham and his work matter to Dancers on a Plane is spelled out literally by the inclusion along the canvas’s bottom edge of the dancer-choreographer’s name, interspersed with the work’s title – the multiple ‘dancers’ referring perhaps to Cunningham’s own. At the time that he was making the painting, those dancers were ones with whom Johns was, in certain respects at least, parting company: the artist had inaugurated the Dancers on a Plane series soon after designing what would turn out to be his last set and costumes as artistic advisor, and the Tate picture was made as he officially retired from that position (although Mark Lancaster, his replacement, had been responsible for the bulk of the work for some time).10

Hardly a rupture, it is nonetheless as though Johns’s withdrawal from the company facilitated its subsequent return in paint.11 The artist has insisted that Dancers on a Plane was ‘for’ Cunningham rather than ‘of’ him, and in Johns’s view making a work ‘for’ the dancer-choreographer meant something quite different outside of the context of the company than it did within it.12 In speaking of his contributions to Cunningham productions Johns has claimed that while he would always follow his ‘own beliefs … my primary interest was to serve his thinking rather than mine’.13 With Dancers on a Plane, it is as if that situation is reversed, and Cunningham’s thinking comes to serve that of Johns. To say that Cunningham is the subject of Dancers on a Plane is not quite right, as Johns suggests – the stencilled words are not a caption. Yet, as this essay will show, the Tate picture does productively take over and transform certain of the dancer’s ideas. Among those ideas, of perhaps greatest significance is a conception of relating to others that Johns came to know through work with Cunningham, and that he ultimately allegorised in the painting.14

Fig.3

Jasper Johns

Untitled 1972

Oil paint, encaustic and collage on canvas with objects

1830 x 4900 mm

Museum Ludwig, Cologne

© Jasper Johns

For the majority of his years as the Cunningham Dance Company’s artistic advisor, Johns’s painterly practice centred on the hatching motif, and in several broad ways this motif bears traces of his experience with dance. According to Johns, his use of hatching was catalysed by the markings on a car of which he had ‘just a brief glimpse’ while driving on the motorway, and we might think of this story as, among other things, a means of building the ephemeral into his work.15 Add to this the fact that the hatch mark as traditionally deployed in the graphic tradition connotes depth through shading and the paintings come to seem, like dance, an art of space and time. There is also Johns’s regular recourse to mirroring as a structural device, which could elicit thoughts of the mirrors in a dance studio; and the body reflected in such a mirror is also often understood as being variously evoked by Johns’s crosshatch works – curator and art historian Mark Rosenthal, for example, has written of abstracted figures in Weeping Women 1975 (private collection) and surrogates for the female body in The Dutch Wives 1975 (collection of the artist).16 It is also worth recalling that the hatching motif debuted alongside plaster casts of body parts in Johns’s Untitled of 1972 (fig.3); being around the many different bodies of the Cunningham Dance Company perhaps allowed Johns soon thereafter to turn away from the body’s concrete rendering without the corporeal falling wholly out of sight.

The movement of bodies in space and time was very much under consideration in the wider art world by the 1970s. The start of the previous decade had seen an increased engagement with dance, owing in part to the efforts surrounding the Judson Dance Theater, the New York-based collective active between 1962 and 1964.17 In addition to showcasing the cutting-edge experiments of self-identified dancers such as Trisha Brown, Deborah Hay and Yvonne Rainer, the Judson also featured artists whose work had traditionally involved a material component, such as Rauschenberg and Robert Morris, providing a space in which they could experiment with movement. Moreover, connections between dance and visual art were brought pointedly to the fore in texts such as Rainer’s 1966 ‘A Quasi-Survey of Some “Minimalist” Tendencies in the Quantitatively Minimal Dance Activity Midst the Plethora, or an Analysis of Trio A’.18 With movement increasingly part of the artistic vernacular, by the end of the 1970s the performance practices of figures such as Vito Acconci, Joseph Beuys and Bruce Nauman were also garnering increased attention, and Johns’s familiarity and engagement with these trends might be identified in his crosshatch paintings made at this time.

Johns’s appeal to dance becomes more pronounced in Dancers on a Plane 1980–1 than in his earlier crosshatchings. To begin with, the painting conjures the (dancer’s) body in a host of ways. Immediately called forth by the work’s title, the picture also approximates a standing figure in height and shares the body’s rough bilateral symmetry. This corporeal quality is heightened by the spine-like white and black line that runs vertically down part of the composition’s centre and by Johns’s representation of testicles at the frame’s base. Because words can be made of the work’s stencilled letters only if we connect the last one on its right edge to the first one on its left, a cylindrical, three-dimensional state of the painting is imagined; the inclusion of mirror-reversed lettering likewise suggests an entity with both back and front.19

While some of these devices are not unique to the Tate Dancers on a Plane, there does appear to be a more specific type of corporeal presence appearing in this work. Of painting his first Dancers on a Plane in 1979, Johns claimed, ‘I thought of Merce Cunningham and how so often his work seems coloured by a kind of unbalanced energy. In the second painting … I tried to show that thought’.20 The energy Johns sought to show came, in part, from the sort of movements Cunningham and his dancers performed. As art historian Douglas Crimp has put it, Cunningham ‘pulls the dancing body apart such that, to the extent that it’s possible, head, arms, trunk, and legs move separately from one another’.21 An echo of this is frequently found in a dance’s continuity: in an early article describing the chance procedures that often stood behind the dancer-choreographer’s treatment of the body, one-time Cunningham dancer Remy Charlip observed that ‘a dancer may be standing still one moment, leaping or spinning the next’.22 Through its many hatch marks the body of Johns’s painting similarly seems to move in multiple different directions at once. Moreover, the large passage of lighter-toned hatches on the right – wholly unlike and unbalanced by their weightier, more clotted mirrored counterparts – possesses a dynamism that suggests the standing work is itself poised for a quick turn to leaping or spinning. The buoyancy of that right-hand section teamed with the composition’s multitude of marks also summons thoughts of the painting body, its dance up, down and across the canvas. With his body quickly pulled this way and then that, variously placing emphasis here then there, the choreography Johns executed in making his all-over painting hardly belonged to Jackson Pollock: it was that of Cunningham.

As Johns took over something of Cunningham’s movements in his painting, he also reflected on what was at stake in them. Cunningham’s non-narrative, often chance-derived choreography placed incredible demands on his dancers, calling on them to execute far from intuitive combinations of movement. Yet as former dancer Carolyn Brown once claimed, ‘Merce does not ask for or want imitation of his own personal style and way of moving’; instead, Cunningham allowed each dancer to discover how he or she might best realise his or her prescribed movements.23

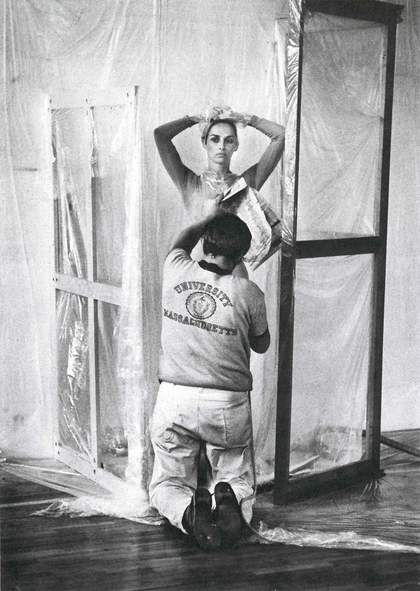

Fig.4

James Klosty

Jasper Johns Spray-Painting Carolyn Brown’s Costume for Canfield 1969

Photograph

© James Klosty

Over the years, Cunningham’s commitment to creating room for his dancers’ idiosyncrasies within his precisely set choreography was variously brought to the fore: in a work like Changing Steps (1973), for example, each performer was given a solo that drew out his or her particular qualities as a dancer.24 It is worth noting that at times Johns’s own work with the company similarly placed the specificity of each body front and centre – the reflective paint of the costumes for Canfield (1969), sprayed onto the garments as the dancers wore them, as documented in a photograph by James Klosty (fig.4). A related responsiveness to bodily particularity informed Johns’s own dance across his 1980–1 painting: roughly keyed to his size, its execution might stand as a testament to his specific reach. Indeed, the potential relevance to Johns’s work of Cunningham’s notes outlining possible actions for dancers in his 1960 Crises, pointed out by curator Jeffrey Weiss, feels especially striking in this context: ‘bend rise extend’, they read.25 Cunningham’s approach to movement also signals a way to think about Johns’s use of and divergence from the underlying pattern of Dancers on a Plane: it is as though by keeping a mirroring principle active Johns insists on the presence of guiding choreography, but within its dictates each bundle of hatches is then left to articulate a distinctive identity. Johns’s whole painting might be viewed as an idiosyncratic realisation of Cunningham’s choreography, as danced by the picture plane.

Space and staging

The all-over quality of the strokes that constitute Dancers on a Plane and the other crosshatch works have often been seen as an engagement with the legacy of Pollock.26 Yet in the instance of the Tate painting it is Cunningham’s conception of space that seems to matter most. Around the time of his dance company’s formation Cunningham wrote, ‘In applying chance to space I saw the possibility of multidirection. Rather than thinking in one direction i.e. to the audience in a proscenium frame, direction could be four-sided and up and down’.27 Consequently, and going against tradition, no section of his stage was privileged. His dancers were instead spread across that space in non-causal relation to one another – fast-paced unison dancing in one area, for example, unfolding simultaneously with an adagio solo in another. The diverse directions of the many hatch marks in Dancers on a Plane brings to mind this innovative decentring of the stage – the tight-knit pattern’s conjuring of terrazzo flooring perhaps a cue for this – as the character of those marks evokes the dancers’ attending dispersion: note the staccato clusters of yellow and white in the upper right, the few slow emphatic strokes of orange just left of centre and the anchoring accumulation of black hatches in the bottom left quadrant.28 The orientation of the painting’s lettering stands as a further disruption of traditional spatial organisation. Moreover, just as the absence of a centre stage leaves the audience for a Cunningham dance without direction as to where to look, the beholder of Johns’s work is forced to choose whether to assess the pattern of the painting as a whole or to attend to the nuances of a particular bundle of strokes. The looseness with which Johns adheres to the work’s organisational scheme adds to the difficulty of keeping the particular and whole in view at once. It is impossible to know what happens elsewhere based on any one set of marks, and such a frustration of logic is also characteristic of Cunningham’s choreography.

The interest in this treatment of space for Johns, as for Cunningham, was in part due to its implications for the relationship between part and whole, long of concern to both artists. In 1957 Cunningham had written that ‘people and things in nature are mutually independent of, and related to each other’, and throughout his career just as important as his engagement with the particularity of his dancers was his sense of the dance as a cooperative effort.29 One of the effects of dispersing his dancers across the stage as they executed movements that bore no causal relation to those of the others was that the idiosyncrasies of each performer came into sharper focus. Yet Cunningham’s repeated recourse to unison work served as a reminder of the fact that the dance always remained a collective undertaking – the stage a site for the coming together of diverse actors. Returning to Dancers on a Plane, then, we might see it as addressing similar questions regarding how idiosyncratic marks can coexist within a whole, at once threaded together and unravelling.

An echo of this might be located outside the field of the canvas within the work’s frame. There, it is as though the diverse clusters of hatches have been disentangled and reconstituted as a series of forks, knives and spoons. This steady repetition of utensils seems keyed to the dance, a certain iterability being one of that medium’s key characteristics. More importantly, while these forms undoubtedly constitute a familiar whole, one underscored by their shared framing, they are also necessarily distinct, each serving a very different purpose. (‘We have learned to use all three’, wrote Susan Sontag, ‘But they can be taken separately, of course’.)30 This gesture towards the possibility of individuality persisting within – even emerging owing to – the group comes across even more forcefully in the painting when we compare groups of, say, the knives. Far from reading as mass produced, each has a singular character, the handle of one ornately decorated, another left plain. Cunningham remarked of his 1968 dance Rainforest, for which Johns arranged to have Andy Warhol’s free-floating Mylar pillows serve as set: ‘it’s a character dance and since such a dance is made specifically on a given body, its flavor changes sharply when some other dancer takes over the part.’31 Not all knives will cut the same.

Johns’s history of involvement in Cunningham productions such as Rainforest may also have proved significant to the shape of the Tate painting in a number of ways. Johns’s aversion to working in the theatre has been observed by the artist himself as well as others, and it had much to do with the rote work required for each production: ‘there is something about the setting up and taking down of things that I dislike’, Johns once remarked.32 Moreover, although he regularly delegated the design of sets and costumes, he was often left to realise them. ‘For instance, I asked Bob Morris to do something, and he had an idea but no interest in doing it’, Johns recounted, ‘So he told me what was to be done, and who else was there to do it except me?’33 The artist’s role as a founding member of the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts left him further engaged in organisational tasks on behalf of Cunningham, among others. Something of this ongoing labour might be sensed in the insistent proliferation of marks across the canvas of Dancers on a Plane. Such everyday labour necessarily resulted in casual, intimate encounters with the Cunningham Dance Company, and something of this, too, is felt in the painting – in the mutual imbrication of the hatches, woven together in, to borrow Johns’s own formulation, the fabric of friendship.34

Johns’s costume and set design

Fig.5

Merce Cunningham’s Un jour ou deux 1973, featuring set and costume designs by Jasper Johns

Photograph

© Jasper Johns

The work carried out by Johns on sets and costumes is significant here too. He is credited with making half a dozen sets along with seven costumes during his tenure as artistic advisor, and his design for Cunningham’s 1973 Un jour ou deux (fig.5), commissioned for the Paris Opéra ballet, might strike us as a blueprint for his much later painting. The design’s scaling from a darker, tighter grey to a lighter, looser one seems to have been adapted by Dancers on a Plane, as has its preoccupation with single dancers and their situation in relation to groups (Un jour ou deux had a cast of twenty-six). Moreover, in its realised form Johns’s design saw dancers performing both behind and in front of two grey scrims – which is to say, dancing against planes.35

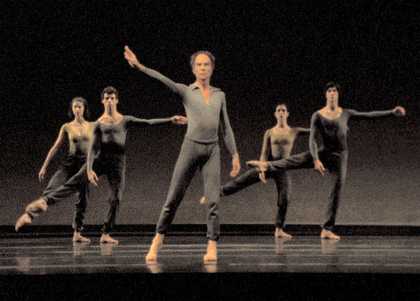

Fig.6

Merce Cunningham and Charles Atlas’s Exchange 1978/2013, featuring set and costume designs by Jasper Johns

Photograph

© Merce Cunningham and Charles Atlas

The last dance to which Johns contributed as artistic advisor was Cunningham’s 1978 Exchange (fig.6).36 The artist’s backdrop and costumes again featured grey heavily, with the costumes also including minimal areas of colour.37 Although there is much to be said about Johns’s designs, it is with Cunningham’s choreography in Exchange that this essay will conclude. This thirty-seven-minute dance was broken into three parts, with half of the company of fourteen in the first part, the other half in the second, and the whole company in the third, with Cunningham present in all three sections. Cunningham has said that the dance made use of the ‘idea of recurrence, ideas, movements, inflections coming back in different guises, never the same’; certain phrases repeat in part or whole across the sections yet are always made different by their new contexts.38 The first group to appear included the newer members of the company, and the older members replaced them gradually as section two started. ‘Watching it’, long-time Cunningham Company archivist David Vaughan observed soon after the premiere of Exchange, ‘is like watching history unfold before your eyes’.39 A notion of recurrence had long informed Johns’s creative output, but we might imagine its new association with his work for Cunningham as proving productive – triggering questions about how his engagement with the dancer-choreographer might resurface in new guises.

More important, however, is the fact that as Exchange premiered in September 1978, Johns’s own history was unfolding before his eyes in the form of his travelling retrospective. Having originated at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in late 1977, Johns journeyed to its opening in Tokyo the month before Exchange was first danced. Against this backdrop, Cunningham’s continuous, recurring presence on stage during Exchange may have had special force for Johns: it modelled the potential productivity of articulating oneself against one’s own history, its changes and continuities, as well as within and across shifting generations. As Cunningham described it, Exchange closed with the whole company moving in ‘separate groups of two or three. It does not stop; it stays in process’ – the work of relating to others, the sort of work considered in Dancers on a Plane, staged as ongoing.40