Fig.1

Sam Francis

Around the Blues 1957, 1962–3

Oil paint and acrylic paint on canvas

2755 x 4875 x 50 mm

Tate T00634

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Around the Blues 1957, 1962–3 (Tate T00634) by the American artist Sam Francis is a mural-sized painting measuring 2755 x 4875 mm, created predominantly in oil paint on woven cotton duck canvas (fig.1). It features an asymmetrical mass of richly coloured globules in multiple tints of blue, from azure to celestial sky to cerulean, as well as deep violet, reds that range from Venetian to Pompeiian, lurid orange, dark to lime green, sunshine yellow, pale pink and inky black. These are split apart by ‘airspaces’ – large areas of gesso, titanium and zinc whites that disperse the bright clusters to the top and bottom and out to the right-hand side of the composition.1

Fig.2

Sam Francis

Around the Blues, detail

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Photo © Debra Burchett-Lere 2019

The loose arrangement of different hues in Around the Blues appears organic, as if the artist simply allowed the paint to fall from the brush. This natural-seeming appearance belies a careful production process, beginning with Francis working out the picture across the entire surface. After priming the canvas with white gesso – where the gesso is both an active ground and an integral colour – Francis built up the composition by brushing on the colours. This included adding white oil paint of varied thickness and consistency onto, and sometimes worked into, the thin, untinted gesso priming layer. Each colour has its place, with their differing intensities guiding their sequential application, which was done with a 3 inch (7.5 cm) brush and timed so that colours could dry and their appearance be assessed before others were added (fig.2).2 During the slow procedure, Francis permitted the vertical dripping, speckling and chance touches of paint to stay, resulting in a variegated and dynamic whole. The gravity-induced movement of the paint has burst the coloured balloon-like shapes into pale drifts and trails that taint the white atmosphere. Around the Blues looks spontaneous, the result of one fluid episode of painting. But as art critic Herbert Read observed in 1957, citing the techniques used by abstract artists like Jackson Pollock, Francis ‘must not be confused with those “action painters” who hope to achieve greatness by riding their brushes as if they were witches’ brooms. He is on the contrary a very deliberate, a highly conscious and conscientious painter.’3

Around the Blues was purchased by the Tate Gallery directly from the artist in early 1964. The canvas is signed ‘Sam Francis ’57’ on the verso, where the title is given as Around the Blue (missing the final ‘s’). It was first exhibited in a solo show at Martha Jackson Gallery, New York between 27 November and 28 December 1957 with the title Round the Blues.4 The press release for this exhibition of sixteen watercolours by Jackson’s rising star artist announced the inclusion of ‘one large canvas ten by sixteen feet, painted in New York’. This statement contradicts the artist’s inventory, which records Mexico City as the location of Around the Blues’s making.5 In turn, Tate’s acquisition record for the work and the notice of its purchase in the Burlington Magazine are tellingly vague on crucial details: these brief texts state that the work was painted ‘mainly’ in 1957 but do not say where, or clarify precisely when the painting was reworked and finished.6 Tate’s file instead contains a series of questions about the painting’s biography in letters sent out to the artist and to overseas curatorial contacts. Francis’s reworking of Around the Blues accounts for the second date given to the work, 1962–3, indicating the uncertainty as to whether the reworking took place in late 1962 or in the first few months of 1963, or both.

This essay charts the itinerary of Around the Blues from its creation in spring 1957 to Tate’s acquisition of the work seven years later, drawing extensively upon unpublished and newly identified archival letters, photographs, shipping records, press reports and curatorial files. As the documentary evidence (or lack of it) for the production and reception of Around the Blues makes clear, no single framework defines or contains the work. The particular history of this painting underscores how artworks are situated like shifting junction points in a complex topography, where geography, politics, artistic practice and social life overlap, temporarily held together in time and space by shared commitments and broken apart by dislocation and faded attachments. Most markedly, this essay shows how the ‘life story’ of Around the Blues exemplifies the accelerated mobility of artists and large-scale artworks towards the end of the ‘post-war’ decade of the 1950s. Such swift transnational movement had far-reaching implications for the positioning of Francis in an internationalised art world and, equally, for the look, making and interpretation of Around the Blues.

Painting’s universalist potential

In New York in April 1950, at a three-day event known as the Artists’ Sessions that consisted of roundtable discussions on pressing issues in modern art, the painter Adolph Gottlieb noted that ‘in the last fifty years the whole meaning of painting has been made international’.7 These remarks, and the proceedings of the Artists’ Sessions more widely, were published the following year in Robert Goodnough’s Modern Artists in America. In the same volume appeared an article by Michel Seuphor titled ‘Paris – New York 1951’, in which the Paris-based critic boldly pronounced abstract art to be a ‘universal language in which every individual can forge his own style with as much originality, felicity and force as his talent and personality allow’.8 A few years later, in April 1958, French critic Michel Tapié asserted in Gutai, the Japanese avant-garde art journal: ‘Art cannot be considered on a scale other than global’.9 Sam Francis’s career trajectory over the course of the 1950s seems to match such certainty about the universal value of abstract art. Martha Jackson’s press release for the 1957 show featuring Around the Blues defined Francis as the ‘first truly international American-born painter’.10 Her claim was supported by the artist’s Europe-wide reputation, a full roster of gallery shows in major capital cities, and mural commissions in New York, Tokyo and Basel. The artist himself was also engaged in almost constant movement around the globe.11 After seven years living and working in Paris, in autumn 1957 Francis visited Japan for the first time and embarked on a whirlwind year of world travel – in addition to Around the Blues, his peregrinations are illustrated, as it were, by paintings with titles such as Round the World 1958–9, 1960 (Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel), Japan Line 1957 (private collection), Mexico 1957 (Ohara Museum of Art, Kurashiki) and Emblem (Two Worlds) 1959, 1963, 1967 (Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas).

In the Artists’ Sessions of 1950, much of the debate time was consumed by the degree to which painting’s universalist potential and modern worldliness entailed the dispersion of values previously held in common, a sense of ‘community’ and the basis for that community – a ‘common vocabulary’, ‘heritage’ or ‘cultural tradition’. Despite Seuphor’s universalist faith in abstraction, he could not help but attribute nation-defined stylistic differences to painting produced on either side of the Atlantic: Parisian ‘velvet’ was compared to the ‘cutting metal’ of New York, French ‘measure’ to American ‘rhythm’.12

Fig.3

Ellsworth Kelly

La Combe III 1951

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

© Ellsworth Kelly

No consensus could be reached, whether on the importance of national tradition or the finish of an artwork, for these inquiries all impinged on the largest and gravest question of all – the meaning of non-figurative or abstract art. It was a question of importance to more than just painters and art critics. Connoisseurial distinctions aside, American customs officials glared suspiciously at an abstract painting by Francis’s compatriot Ellsworth Kelly – La Combe III 1951 (fig.3), painted in Paris and en route to Boston for exhibition – suspecting it of representing treasonous secret code. As art historian John Curley observes, abstract art’s transatlantic mobility and departure from standard categories of naturalistic representation turned it into a highly contested site of meaning, resistant to containment and open to interpretation.13

The cosmopolitan credo ‘the history of painting is linked to that of humanity’, pronounced by Algerian artist Mohammed Khadda in 1964 and likely a view shared by Francis, promised art as a counter-weight to imperialist ambitions and Cold War barricaded frontiers.14 But the descriptors ‘global’ and ‘international’ deserve careful qualification despite their open-border cachet. During the 1950s these terms indicated artistic networks based in city centres sited within the ‘Free World’ or Western-bloc geography (such as Paris, London, Tokyo, New York, Amsterdam, Bern, Stockholm and San Francisco). Art historian Hiroko Ikegami points out how this mapping exercise charts the ‘global rise of American art’, corresponding to the nationalised and divided political world of the time.15 Ikegami’s case study is neo-dada and pop art, epitomised by Robert Rauschenberg’s world travels and his Grand Prize win at the Venice Biennale in 1964. In contrast, and in direct competition with Rauschenberg, Francis was a key participant in the transnational ‘rise’ of gestural or informel abstract painting over the course of the 1950s.16

Fig.4

Sam Francis

For Fred 1949

Oil on canvas

1498.6 x 1016 mm

Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Bearing in mind these limitations on the scope of the term ‘international’, Francis’s cosmopolitan career and the intercontinental travels of Around the Blues suggest the potential for opening out and nuancing national art histories. From the start, Francis moved sideways in relation to expectations. He completed both a bachelor’s degree and a masters at the University of California, Berkeley, achieving local success in showing his biomorphic, surrealist-inflected paintings, and in 1950 he seemed set to flourish as a member of a burgeoning school of Bay Area abstraction, connected to but independent from New York. For those who knew him, such as his close friends and fellow artists Jay DeFeo and Fred Martin, there was no doubt as to Francis’s commitment to painting above all else, and a fluid, open abstraction as its primary form of expression (see, for instance, For Fred 1949; fig.4).17

Fig.5

Clyfford Still

PH-128 1948

Oil on canvas

1358.9 x 1136.7 mm

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

© City and County of Denver, Courtesy of Clyfford Still Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.6

Hans Hofmann

Ecstasy 1947

Oil on canvas

1727.2 x 1527 mm

Berkeley Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley

© Hans Hofmann

Nonetheless, for both West and East Coast American artists, the question of European – specifically, French – influence was a much-debated topic. Clyfford Still, who headed up the graduate painting programme at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco in 1946–50, took an aggressively parochial stance against European artistic traditions, advocating an unconstrained individualism expressed in direct brushwork, expansive spatial designs and organic colour (see, for example, Still’s PH-128 1948; fig.5).18 This position was not necessarily shared by many of Still’s colleagues, from Europe-born painters such as Willem de Kooning, Hans Hofmann – whose vivid colours, bold brushwork and modernist teachings at the University of California during the summers of 1930 and 1931 left a legacy for Francis and fellow Bay Area abstractionists to absorb (see Ecstasy 1947; fig.6) – and Mark Rothko (another important figure in colour field abstraction, whose impact upon Francis was significant), to Robert Motherwell, with his open homages to French culture, and Franz Kline with his Anglophilia.19 Disregarding Still’s opinion that modern American art should be self-sustaining, and fresh from instructor Erle Loran’s lessons on French painter Paul Cézanne’s (1839–1906) core creative principles of painting, Francis decided on France as a change of scene after graduating. He moved to Paris in 1950 together with fellow artist Muriel Goodwin.20

Fig.7

Jay DeFeo

Untitled (Paris) 1951

Berkeley Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley

© 2019 The Jay DeFeo Foundation

By all accounts, Francis and Goodwin slotted quickly and easily into the well-established artistic and literary colony of Americans in Paris. In 1950 Paris’s power and prestige as a cultural hub had not yet waned and the city provided a crucial training ground and politically liberal refuge for short-term visitors and long-term exiles alike. Like Francis and the acquaintances he met in Paris, such as American painters Norman Bluhm and Al Held, many were war veterans who met the requirements for receiving a G.I. Bill stipend of $75 per month by enrolling at one of the well-known teaching ateliers. These included that of Fernand Léger in Montmartre, which Francis briefly attended.21 For women artists such as sculptor Claire Falkenstein or painter Shirley Jaffe, who became a firm friend of both Francis and Goodwin and life-long Paris resident, the city offered liberation from home-bound expectations and domestic constraints. Francis’s San Francisco ally Jay DeFeo visited Paris in 1951 as only the second female recipient of a travel fellowship from the University of California, to make a body of ‘grey’ paintings that grounded her work for years to come (see, for instance, Untitled (Paris) 1951; fig.7), while his close friend, art critic Rachel Jacobs, was family-funded to study philosophy, arriving in 1953.22

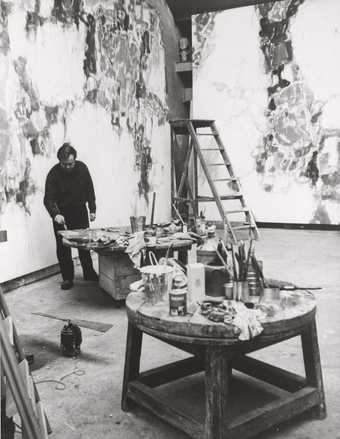

A large studio

Fig.8

Sam Francis’s studio in Arcueil, Paris, with In Lovely Blueness (No.2) 1955–6 at the centre

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.9

Sam Francis

In Lovely Blueness (No.1) 1955–7

Oil on canvas

3000 x 7000 mm

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019/ADAGP, Paris

Fig.10

Sam Francis in his Paris studio, c.1958, working on the Basel Mural 1956–8

Betty Freeman Papers, 1951–69, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Photo: Georges Boisgontier

As his letters home to his father and stepmother attest, in addition to Cold War politics and existentialist philosophy Francis’s overriding concern in Paris was to obtain a sizeable, well-lit space in which to paint: ‘the vision that haunts me is one of a large studio with lots of light, light and more light’.23 Without such a space, canvases of the size of Around the Blues could only exist conceptually. In March 1952 Francis described his need for ‘a place at least 50 feet long, 40 feet wide and 35 feet high. Have been doing paintings lately 10 feet high 7 feet wide; have had to stop of late though as it is too expensive.’24 Size was not simply about physical gigantism, but corresponded to the spatial and perceptual expansiveness that Francis and many other abstract painters felt would provide an immersive environment for the viewer to experience. In early 1956, boosted by increased sales of his work, Francis moved with Goodwin into his largest studio yet, situated in Arcueil in the Parisian suburbs (fig.8). It was described by artist Jon Schueler as ‘the biggest barn of a place you can possibly imagine … impossible to heat of course … but huge skylights and lots of space.’25 Here, a year before he painted Around the Blues, Francis was able to start executing the kind of very large compositions that were in line with his desires. In addition to important precedents to Around the Blues, such as the painting In Lovely Blueness (No.1) 1955–7 (fig.9), he was most preoccupied with three panels, each 3850 x 6030 mm in size, that would become the Basel Mural 1956–8 (fig.10; these were subsequently divided into three individual works and are held in the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, and in a private collection in California). In these works, white areas of varying dimensions open out the brightly coloured globules and skeins of paint to create a luminous patchwork of shiny and matt whites, delicately tinted and shadowed with thinned fluid colour.

Although closely linked to these Paris-made canvases, and even overlapping with them in the extended time of its production, Around the Blues was not painted in Francis’s barn-like Arcueil studio, but in Mexico City and New York. At the end of 1956 Francis wrote to his New York dealer, Martha Jackson, to let her know that:

plans for the year still not all settled but have been offered a mural for school in Japan in Sept. – will do all to get there – until then want to stay in America + Mexico. Would like to do some large murals in the states and have one possibility in America will know more about it when I get there. Do you have any ideas in that direction? Also would like to paint some in N.Y. Hope to leave for Japan in August and then take the India way back to Paris. Will show 5 paintings at [Arthur] Tooth in London in January. One more show in the museum in Japan also. So that’s all my painting gossip!26

Francis followed his letter in person shortly afterwards, arriving in Manhattan on 20 January 1957 and immediately starting work on a mural painting for the directors’ lounge of the Chase Manhattan Bank (fig.11). Although not completed until 1959, the prolonged process of producing drawings and studies for the mural, which measures 2489.2 x 1158.4 mm, was surely important for the more rapid creation of Around the Blues a month or so later.27 Yet this is a matter of difference rather than contiguity. While the long horizontal ground of the Chase Manhattan mural is divided vertically into four segments, with the colour clearly contained in angular forms, the two iterations of In Lovely Blueness (painted in 1955–7, fig.9, and 1955–6), the unfinished Basel Mural panels and Around the Blues all feature a much looser, more fluid effect.

Fig.11

Sam Francis

Chase Manhattan Bank Mural 1959

Oil on canvas

2489.2 x 11582.4 mm

JP Morgan Chase Art Collection

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.12

Sam Francis

Painting 1957

Tate T00148

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Unlike most of Francis’s studios, there is minimal documentation of his work done in Mexico City. The studio was apparently in a six-room apartment across from the historic and extensive Chapultepec Park that was taken by Francis and the artist Carol Haerer after they arrived on 12 March 1957. In an undated letter, Francis reports his outsider’s fascination with a city that he describes as ‘not at all Spanish’ but ‘utterly and always to be Indian-Mayan Aztec or what you will but for ever and ever ancient and close to the old gods’.28 He does not say if he visited the magnificent ‘Aztec’ art deco-style Palacio de Bellas Artes, situated close by in Chapultepec Park and home to one of José Clemente Orozco’s most impressive public fresco murals, Catharsis 1934, with its lurid and tragic depiction of revolutionary violence.29 Perhaps he refrained from museum visits, as during his time in Mexico City he was extremely productive. Having brought painting supplies with him, Francis completed Mexico and numerous watercolours, and commenced six other oil paintings. Most of the watercolours travelled direct from Mexico City to London for an exhibition of his work at Gimpel Fils in May and June of that year – including Painting 1957 (fig.12), acquired from the show by Tate – and then on to Galerie Kornfeld in Bern for an exhibition that opened on 25 September.30

Exhibiting Around the Blues

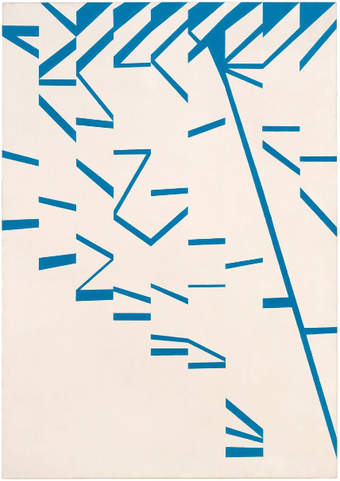

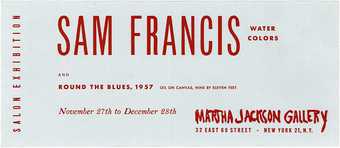

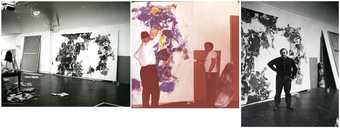

Fig.13

Invitation card for Sam Francis: Watercolors and Round the Blues, Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, 1957

Image courtesy of the Martha Jackson Archives, University at Buffalo Anderson Gallery, State University of New York at Buffalo

Around the Blues was shipped from Mexico City to New York, where Francis worked during July and August 1957 before departing for Japan in September. In mid-October Martha Jackson wrote to Francis in Tokyo to announce that: ‘ROUND THE BLUES and your watercolours will be exhibited November 27 through December 28 concurrently with Mme. [Germaine] Richier’s sculpture. I hear the “Life” article will be published December 2 – we are quite happy about this coincidence!’31 (fig.13) In the rooms of the gallery that were dedicated to Francis, Round the Blues (as it was titled on this occasion) was the monumental centrepiece, the only oil painting amid a sea of watercolours. Jackson reported to Francis:

your show opened quietly the day before Thanksgiving. The same day as the Richier. They actually are two separate shows and separate notices were sent to our mailing list. For yours we only mailed a card, blue with red printing – very nice looking … The two shows together are really exciting.

The pairing with sculptor Germaine Richier must have seemed apt, in that Richier was closely associated with the existentialist and surrealist milieux around Francis in Paris.32 Jackson went on to describe the hang of the rooms dedicated to Francis:

Your big oil is stretched across the upstairs room in front of the windows. It fits in as if it were made for the spot. We have it hung on very simple aluminium poles which show a little top and bottom. It looks wonderful as it hits you smack in the face as you enter the entrance, and of course you see part of it as you get off the elevator & walk toward the entrance to this room. The watercolours are hung in the outside large hall across from the elevator and at the end of the room opposite the big oil. I left about 15 feet [4.5 m] of white wall between the two large water colours and the oil so when you look at it you don’t see anything but white wall.33

Jackson wrote again early in the New Year to say, with glee:

we are now in the class of dealers yelling and screaming for paintings! It seems your watercolours sold out.… Congratulations on being such a fine artist and all send you our best. Oh I forgot to tell you we had ROUND THE BLUES beautifully installed across the windows on 2nd floor held only by aluminium poles, which hardly showed. There was just a perfect proportion of air space around the painting and it looks very handsome and is still there.34

Imagining how the painting must have appeared to float in white space due to its discreet fixtures and proximity to the window, Francis replied: ‘Thank you so much for presenting Round the Blues that way it sounds as I dreamt it should be seen!’35 His satisfaction refers to his long-held desire for a dematerialised and expansive expression of pictorial space, unbounded by a frame or wall.36 A decade later, the curator James Johnson Sweeney used wires to suspend unframed paintings by Francis from the ceiling of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston to achieve this effect (fig.14).37

Fig.14

Installation view of the Sam Francis retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1967

Archives of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Photo: Allen Mewbourn

However, Around the Blues could not stay in the gallery forever and it had not yet found a purchaser. On 22 January 1958, Jackson wrote to ask whether Francis would permit her to

offer ROUND THE BLUES to be placed on exhibition-loan in Wellesley’s new Building of Fine Arts designed by Marcel Breuer (as yet unfinished), for two years, hoping the funds for purchase would become available during that period? … The painting is still on exhibition but must come down and be rolled on January 25th.38

Although he was concerned about the long loan, Francis acquiesced to Jackson’s suggestion.39 Yet before it could go to Wellesley – a liberal arts college in Massachusetts – circumstances for the painting swiftly changed. Insured for $5,000, Around the Blues was flown to Mexico City for display in the First Inter-American Biennial of Paintings and Graphic Arts at the Museo Nacional de Arts Plásticas, held from June to August 1958. The artists and works in the US section of this important new showcase were selected by curators at the Brooklyn Museum in New York on the request of the US Information Agency. Around the Blues was marked as reserved (not for sale) by Martha Jackson, who in April 1958 wrote to Jack Gordon at the Brooklyn Museum to say: ‘I thought you would enjoy reading this enthusiastic letter from John McAndrew [at Wellesley] about the Francis painting going to Mexico. Do send him clippings to help him sell it to the alumnas!’40

Fig.15

Installation view of the Mexico Biennial, Mexico City, 1958

Brooklyn Museum Archives, Brooklyn. Records of the Department of Painting and Sculpture. First Biennial Inter-American: Paintings and Prints (06/06/1958 – 08/24/1958)

The biennial was designed to be the first of its kind to survey the art production of the Americas, both North and South. Its contentious reception was noted in the Brooklyn Museum’s Bulletin, where it was proudly reported that the twenty artists’ works in the US contingent shown in Mexico City (including Francis, Josef Albers, de Kooning, Gottlieb, Morris Graves, Grace Hartigan, Kline, Kenzo Okada, Richard Poussette-Dart and Mark Tobey) were the ‘largest and most provocative of the entire assemblage’, catalysing a ‘tumult of comment’ (fig.15).41 It is hard to know whether any positive news clippings on the American abstract works were sent from Mexico City to McAndrews at Wellesley. Much of the comment in the Spanish-language press focused on the exorbitant cost of the exhibition, underwritten by the Mexican government, and the selection and prize-awarding procedures that had excluded many artists whose work did not correspond to the state-sponsored figurative, social realist style. In turn, numerous critics defended art that legibly reflected social reality and pointed to the dehumanising and anti-revolutionary dangers of abstraction, a stance connected to the Cold War polarisation of cultural politics and Mexico’s high standing as a political counterweight to the United States.42

Fig.16

Sam Francis

Blue in Motion (No.3) 1960, 1962

Private collection

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

As it turned out, the contentious reception of abstract art in Mexico City mattered little to the fate of Around the Blues. Upon the conclusion of the biennial, the painting was flown ‘at once’ to Wellesley College in two boxes, one for the unstretched canvas on a roller and one for the stretcher bars, to be re-stretched for display in the ‘Opening Exhibition of the Museum’.43 Yet despite the stated enthusiasm for the work and the intention to purchase, the painting was obliged to return to New York when the inaugural exhibition for the building ended in December 1959, at which point it was most likely stored in Francis’s loft studio at 940 Broadway and 22nd Street, which he had taken on in the autumn of that year.44 It was in this enviable, white-walled space, with natural light pouring through a large skylight, that Around the Blues was reworked by Francis, most likely in late 1962 or in the first few months of 1963, or possibly both. Although he had moved to a new phase of work in the form of his Blue Balls series (see Blue in Motion (No.3) 1960, 1962; fig.16), it seems he had not lost interest in a painting whose composition and features referred back to an earlier and concluded phase of his life – clearly demarcated by Francis’s world travels in 1957–60 and his hospitalisation in Switzerland for many months in 1961 – and whose making had happened at such a pivotal moment in his career.

Reworking the painting

Immediately upon purchase of Around the Blues in early 1964, Ronald Alley, Deputy Keeper at the Tate Gallery, wrote to Francis to ask about the reworking or finishing of their prized new painting, and to Wellesley College to obtain comparative details on the look of the work in 1958.45 Francis replied promptly to say that Around the Blues

was reworked in 1962. Certain colours were strengthened, mostly blues. Also, the whites were cleaned up and retouched where needed. The white is actually the ground. The ground is made up of liquitex gesso white. The painted parts are painted with Winsor-Newton oil colour, thinned with turpentine, in to which has been added a bit of varnish. Also, some colours are painted with Magna colour, a plastic paint made by Shiva, often mixed with oil paint.46

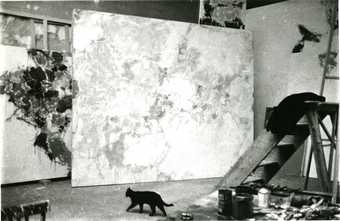

Tate’s acquisition record quotes Francis’s description of his paintwork verbatim, with the added comment that: ‘comparison with a photograph of the original taken when the picture was on loan to Wellesley College in 1958–9 confirms that no very radical changes were made during the reworking. The main differences (colour power) seem to be that the artist tended to soften the rather rigid images of the shapes and to give the whole composition a looser and more fluid character.’47

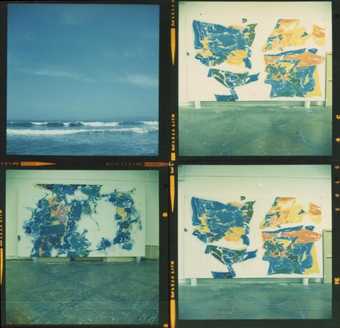

Fig.17

Sam Francis’s studio on Broadway in New York, 1962 or 1963, with Around the Blues before reworking

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

A black and white photograph taken in the Broadway studio in 1962 or 1963, prior to any significant reworking, and a later but undated sequence of photographs taken during the reworking process on Around the Blues, adjusts Tate’s assessment.48 The photographs indicate that the changes were subtle and important, involving an attentive rethinking of the composition as a whole (fig.17). The reworking of the painting significantly reoriented the design of the coloured forms on the white ground away from the harsh angularity, splintered shapes and awkward irresolution of the Chase Manhattan Bank Mural, which Francis had finished in the Broadway studio in 1959. The softening effect of the additional paintwork equally sets Around the Blues apart from Mexico, which had been completed in the same Mexico City studio in spring 1957, and has a much more intense and saturated tonality in the red, yellow and blues, and fewer washy, fluid areas.49 Instead, after reworking, the more ethereal look of Around the Blues harks back to the liquid colour, cloud forms and transparent, pale atmosphere of Francis’s Paris paintings of the mid-1950s, such as the Basel Mural and the two paintings titled In Lovely Blueness. But equally, the revisions align it with the gravity-defying cellular forms populating a window-like white surface in the paintings leading to the Blue Balls series of the early 1960s (see fig.16).

Tate’s condition report on Around the Blues observes that the canvas is stained through to the reverse with the first application of paint done with Liquitex gesso white.50 In some areas, this sealing imprimatura, or initial layer, is doubled, where the artist has applied additional overlapping brushmarks to form a thickened ground on which the vibrant colours are then painted. Francis’s method of outlining a composition directly onto the bright white prepared ground using a large, round-headed brush may have been used to ‘draw’ in barely visible outline the blocky left-of-centre column of colour in Around the Blues and the appendage curling out and downwards into the space at the right. In this sense Francis’s process could not be further from an unrevised, ‘one-shot’ application of pigment onto an unprimed support, yet from the moment of laying down the thin white ground onwards, there was no room for revisions or erasures.51 As Francis explained to writer Betty Freeman:

All my mistakes are left in the painting. I will add something but never alter or remove. If I have a blue I don’t like, I don’t work at it and change it to another blue. I add another colour to it, like black or green. But the original blue will still be there at the side.52

To enhance these additions in colour and texture, and to achieve the transparent depth effects of watercolour, as early as 1958–9 and certainly by the early to mid-1960s Francis regularly combined inexpensive, oil-based coloured paints (such as Winsor and Newton and Bocour Holiday, jars of which can be seen on Francis’s work table in fig.17) with quick-drying acrylic emulsions in the same painting, ‘sometimes side-by-side, sometimes overlapping’.53 Around the Blues is an example of this coexistence of media, with most of the colour areas done with oil film diluted with turpentine (presumably in 1957), plus a little varnish, and others done later in solvent-based acrylic Magna paints, in an extremely liquid impasto at ‘1/16 of an inch maximum thickness’.54

Mixing up the paint media allowed Francis to rebalance the forms in Around the Blues, loosen up their edges, and enhance the colouration, possibly including the black pigment that he used to revivify the intensity of the chromatic contrasts; note especially the dense passages of black at the top of the painting that set off the vivid reds and watery blues. To obtain what Tate described as the ‘looser, more fluid character’ that makes Around the Blues quite distinct from Mexico or Round the World – with their vertical arrangements of demarcated, compressed forms, cleaner-edged despite the many dribbles – Francis evidently worked over the entire canvas, brightening the whites and blues and allowing new drips, spatters and translucent stains to dissolve the edges and suggest depth. The largest ‘retouch’ is the addition of a blotchy blue rectangle in the lower right corner, as a kind of heel to the hanging ‘boot’ – an extra appendage that re-weights the whole by filling in a little more of the white space on that side.

Figs.18–20

Sam Francis’s studio on Broadway in New York, 1962 or 1963, with the reworked version of Around the Blues

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.21

Sam Francis’s studio on Broadway in New York, 1962 or 1963, with the reworked version of Around the Blues and Emblem (Two Worlds)

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.22

Sam Francis’s studio on Broadway in New York, 1962 or 1963, with the reworked version of Around the Blues (far wall), Emblem (Two Worlds) (left) and Blue Balls VII 1962 (second from left)

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Further photographs taken in the Broadway studio reveal this process of reworking. A side-on view shows the addition of the blue rectangle and other coloured stains and dribbles, with pots of paint on the floor nearby (fig.18). An amusingly staged colour photo reveals the most reworked area in close-up, with an unidentified friend or colleague appearing to be in charge and gesturally applying more blue to the main body of the colour block, while Francis stands to the side merely touching up the edges with white (fig.19). In dark shirt and belted trousers, Francis takes ownership of the work in another view, most likely signifying completion (fig.20), as does another colour image juxtaposing Around the Blues with an open sea and skyscape and with Emblem (Two Worlds) (fig.21). In a final black and white photograph, Around the Blues has been shifted to the end wall of the studio, a larger chassis propped against it like a window framing a view, while Emblem (Two Worlds) is up on blocks facing the paints table with Blue Balls VII 1962 (collection of Ruth and Ted Baum, New York) alongside it (fig.22).

On the move again

Martha Jackson took advantage of Francis’s studio labours to show both Around the Blues and Emblem (Two Worlds) in a ‘little retrospective’ of oil works, watercolours and lithographs that opened on 4 June 1963.55 Francis forgot about this outing for Around the Blues when he responded to Tate in 1964, writing that it had ‘never been exhibited anywhere else since it was retouched’.56 Perhaps this memory slip occurred because not only was Francis travelling again, and his break with the Martha Jackson Gallery was unfolding, but a few months after Francis’s summer 1963 show the canvas was again sent away, this time to Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

On 9 September 1963, the inaugural Dunn International: An Exhibition of Contemporary Painting opened to the public at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton. This rather monstrous survey exhibition was organised by art historian John Richardson from London, with an expert panel to advise, on behalf of the philanthropist and art and racehorse collector Marcia Anastasia Aitken, Lady Beaverbrook, and her second husband, the Canadian peer and press baron Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook. The intention was to stage an exhibition of the hundred or so ‘leading artists’ of the world in order to honour Lady Beaverbrook’s deceased first husband, the wealthy Canadian industrialist and art collector Sir James Dunn, and to edify the public as to true good taste and value in contemporary art.57 Lord and Lady Beaverbrook’s taste veered strongly towards narrative and naturalistic figuration (in addition to the work of surrealist Salvador Dalí) and they had to be reassured by Richardson that in his selection of artists he had worked to lower the ratio of abstract artists in relation to figurative artists.58

Round the Blues – as it was titled for this exhibition – was sandwiched between smaller paintings by Pierre Soulages (a frequent curatorial juxtaposition, even today), Alberto Burri, Ceri Richards and Victor Vasarely, and emerged from the crowd as one of two abstract paintings and four figurative works awarded prizes of $5,000 each. The other abstract work was by the Japanese artist Kenzo Okada, resident in New York since 1950 and also represented by Martha Jackson. Jackson telegrammed Francis with the news and scribbled a quick letter the same day:

We are thrilled that your painting won & would have had first prize if there was one. Even Lady Beaverbrook liked it tremendously & exchanged compliments with me in front of about 12 people when I was introduced as ‘responsible’ for sending it.… I am mailing an envelope full of funny clippings … Mrs Eaton wants to buy Round the Blues for about $25,000, & will let it go to the Paris show – what do you think? She has a fabulous collection & will hang it on a whole wall of her house in Toronto.59

One local critic wrote: ‘For many, Sam Francis’s 108 x 192 inch oil on canvas was the outstanding work of the exhibition. Entitled “Round the Blues”, it is a huge and magnificent swirl of colour … a painting which bursts on the senses with an almost physical shock.’60

But yet again, despite enthusiastic press and Jackson’s high hopes of a sale, no purchase was settled. Around the Blues was brought to England, arriving by air from Montreal to London on 24 October, and was delivered into the hands of the Arts Council for the second leg of the Dunn International at the Tate Gallery (14 November – 14 December 1963). Although the reviewer for Arts Magazine, Gene Baro, found the whole enterprise of the Dunn International laughable and Tate’s hang simply ‘terrible’, he declared a sense of relief upon entering the abstract room to find paintings by Francis, William Scott and Alan Davies demonstrating ‘intelligence and a sense of decorum’.61 No doubt, too, the Canadian prize must have helped Around the Blues finally secure a permanent home at the Tate Gallery. Compared to Tate’s anxious hesitation a decade earlier over the purchase of an unreservedly abstract painting by Pierre Soulages, there was no quibbling about the Francis acquisition and no fuss was made over the asking price of $25,000.62 ‘Delighted your picture to enter collection’ telegrammed the museum’s director John Rothenstein to Francis on 8 January 1964, following up with a second missive declaring that: ‘The Tate’s acquisition of your Dunn painting will give widespread pleasure in this country, in particular, I believe, among younger painters.’63 This was a major sale for Francis, if Jackson’s warning to the artist in December 1963 about falling prices for abstract art is to be believed.64 Francis did not appreciate the advice or Jackson’s demand for more work to sell and, perhaps as a consequence, he handled the sale of Around the Blues to Tate personally, much to his dealer’s chagrin.65

Sam Francis in England

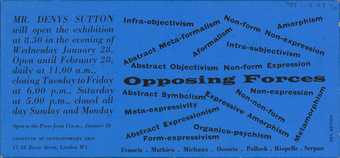

Fig.23

Invitation to the private view of the exhibition Opposing Forces, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1953

Tate Archive TGA 955/1/12/45

By the time of Tate’s purchase of Around the Blues, it was over a decade since Francis’s work had been introduced to the public in England. Indeed, in the five years prior to the Dunn International there were numerous opportunities to view his distinctive contribution to the broad category of informel abstraction. Three paintings had been shown in London in January and February 1953, appearing alongside work by Jackson Pollock, Georges Mathieu, Henri Michaux, Alfonso Ossorio, Iaroslav Serpan and Jean-Paul Riopelle, in Opposing Forces, curated by Peter Watson and Michel Tapié at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) (fig.23).66 Although artist and critic Patrick Heron was critical of works belonging to the ‘decorative wing of the present non-figurative moment’, artists Terry Frost and Adrian Heath were among those who took note of Francis’s works and their impressive ‘all-over quality like parchment’.67 One of the canvases in the ICA show, which Francis described as a ‘large whitish painting’ (White 1952, private collection, Cologne), had been specially chosen by Francis for the house of the famed Bloomsbury patron of the arts, Mary Hutchinson.68 Hutchinson’s generosity ensured Francis’s entrée into British collections and support for his work, notably from critic and art historian Herbert Read.69

Fig.24

Cover of the catalogue for the Arts Council’s exhibition Abstract Impressionism, 1958

Tate Archive

By 1956 Francis’s feature slots in New Trends in Painting: Some Pictures from a Private Collection, curated by Lawrence Alloway for the Arts Council,70 and Recent Abstract Painting at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, seemed only too appropriate, as critics such as David Sylvester and Patrick Heron celebrated Francis’s dominant ‘position at one of the extreme poles of pictorial expression’.71 In 1957 Francis showed in the group exhibition The Exploration of Paint at Arthur Tooth and Sons and had a solo show, Sam Francis: Oil Paintings and Watercolours, at Gimpel Fils, with a glowing catalogue essay by Read. In 1958 Francis was an obvious choice for inclusion (alongside Bluhm, Joan Mitchell, Riopelle, Nicolas de Staël, Heron, André Masson and Richard Smith, among others) in Abstract Impressionism, again curated by Alloway for the Arts Council with a catalogue designed by Smith (fig.24).72

Francis’s burgeoning reputation in England in the mid-1950s was also an important facet in his transnational success, such that Jackson advocated at this time that he think about a residency in St Ives, Cornwall, to further enhance his artistic production and international cachet.73 In December 1955 Life magazine had proclaimed Francis ‘the hottest American painter in Paris’, noting more generally that, ‘Migratory like all Americans, the young painters have moved about the country and around the globe, testing techniques, absorbing new ideas and old traditions.’74 Time followed suit in early 1956, celebrating Francis’s sale of a painting for one million francs.75 Jackson’s aforementioned sales-talk description of Francis as ‘American-born’ but ‘international’, emphasising to her New York buyers that he ‘lives in Paris’ and his work appeals to the ‘avant-garde art circles of Europe’, seemed justified.76 Prestigious outings for his work included Tendances actuelles at the Kunsthalle, Bern in 1955; 50 ans d’art moderne at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels as part of the World’s Fair, where Summer I 1957 (collection of Mitzi and Warren Eisenberg, New York) elicited rapturous praise from Read in the multi-lingual international art magazine Quadrum;77 and the sprawling, high-profile survey of modern art entitled Antagonismes at the Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris, in February 1960, underwritten by the Congress for the Liberty of Culture, with a catalogue preface by Read. The frequent display and enthusiastic critical reception of Francis’s work in England and Europe laid the foundation for Tate’s acquisition of Around the Blues in 1964.

An ‘American’ painting?

Fig.25

Installation view of The New American Painting, Tate Gallery, February – March 1959, with Sam Francis’s Composition in Blue and Black 1954–5 (centre left; private collection) and Big Red 1953 (centre right; Museum of Modern Art, New York)

During this time Francis’s paintings were also being recuperated for exhibitions asserting the American presence in the international scene, but not without qualification. Although Francis cut a serious figure in Twelve Americans at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1956, Alloway scoffed at fellow critics who lauded Francis as a ‘founder of American non-figurative art’.78 A draft biographical note from the Brooklyn Museum in 1958 sums up the confusion: Francis ‘went to Paris in 1950 where he lived until [crossed out: 1957] recently. He now lives in [crossed out: New York] Paris. Check.’79 The Parisian taint seemed strong and not always desirable: Sylvester gushed that upon walking into Francis’s show at Gimpel Fils in London in 1957, ‘beauty comes at you like a scent by Lanvin’, referring to the well-known Parisian perfumier and designer.80 Reviewing Francis’s 1957 Martha Jackson Gallery show at which Around the Blues was first exhibited, critic Fairfield Porter noted the artist’s ‘great reputation amongst the English critics. What do they like about him? It seems to be his colour. The reds and blues have a watercolour flowery lightness that no other Action Painter shows.’81 The following year MoMA featured Francis in the touring exhibition The New American Painting; seen as the triumph of American abstract expressionism on the world stage, this show opened at the Kunsthalle in Basel in April 1958 and travelled to Milan, Madrid, West Berlin, Amsterdam, Brussels and Paris, before a last leg at the Tate Gallery in London in February – March 1959 (fig.25). Yet curator Alfred Barr’s essay for the show’s catalogue described Francis ambiguously as the ‘unique’ expatriate ‘whose reputation was made without benefit of New York’.82

Luckily for Tate, Around the Blues is an irrefutably ‘big picture’, to use Alloway’s words.83 Indeed, prior to shipping the work to Fredericton in 1963, panic ensued about the work’s size, with the gallery’s director writing to John Richardson: ‘OWING TO PROPORTIONS FIND IT IMPOSSIBLE FOR SAM FRANCIS PAINTING TO ENTER BUILDING’.84 With its outsized dimensions, Around the Blues could not be easily moved and the painting had to be taken off its stretcher, rolled, and then re-stretched each time.85 Although Francis’s liquid facture and relative absence of vigorous gestural brushwork could seem suspiciously anti-heroic, the sheer size of Around the Blues allowed the Burlington Magazine to congratulate Tate on a ‘major addition’ to their ‘collection of modern American paintings which also includes pictures by, among others, Rothko, Pollock, Guston, Brooks, Avery, and Tobey’.86 Francis is linked here primarily to the so-called ‘first generation’ of New York abstract expressionist artists, notwithstanding Tobey’s West Coast (and Parisian) affiliation and Guston’s ‘second-generation’ and ‘Abstract-Impressionist’ credentials. Francis was not situated alongside either Kenneth Noland or Morris Louis, though Tate had already acquired paintings by both artists, and Francis had been incorporated along with them into critic Clement Greenberg’s scheme for painting after abstract expressionism in the exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1964. Even though Around the Blues had finally found a permanent home, both artist and artwork again evaded generational or national identification, style markers, or critical and institutional taste.

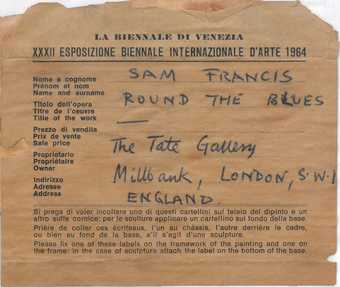

Fig.26

Shipping label for the 1964 Venice Biennale that was found attached to the stretcher of Around the Blues

Tate Conservation File

Given the difficulties with transporting Around the Blues, it is surprising to learn that almost as soon as Tate took possession, it was sent off again, this time to Italy for the 1964 Venice Biennale. At least, this is what is suggested by a label that was found pasted to the painting’s stretcher (fig.26); yet there are no shipping documents recording this journey, nor do catalogue entries indicate the presence of the painting in Venice in that year.87 Of all possible destinations, however, it seems apposite that Around the Blues – its title connoting desire, dark memories, poetic dreams of the divine, and endless voyages to ‘far-off blue places, toward the bright edges of the earth’88 – might have flown to the city that floats between sky and sea and supplies so many of painting’s precious colours. The mysterious Venice label on Around the Blues, preparing it for a journey that it did not actually make, symbolises the travels of this oversized painting on its ill-fitting chassis, re-stretched and hung on the white walls of modern art spaces. Taken together, each shipping invoice and label, each newspaper notice and review in the migratory art magazines of modernism, is evidence of painting’s long-time status as a mobile, transferable art form and of the newly enhanced international identity of both artists and artworks in the decades after the Second World War.