Fig.1

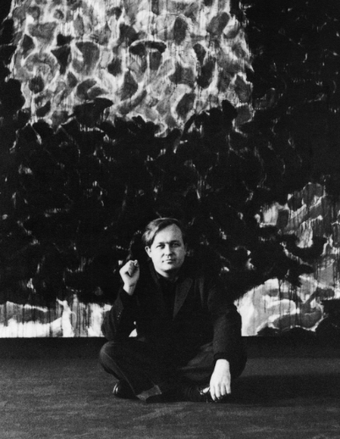

Michel Tapié at Galerie Rive Droite, Paris, 1954, with artworks for the Individualités d’aujourd’hui exhibition, including a Jean Dubuffet painting and calligraphies by Mark Tobey (in front of Tapié), canvasses by Alfonso Ossorio and John Hultberg with Sam Francis’s Black and Yellow 1953–4 (Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf; all behind Tapié), sculptures by François Stahly (centre) and Étienne Martin (far doorway), and paintings by Ruth Francken, Iaroslav Serpan and Jackson Pollock (right)

© Life magazine

In October 1954, paintings by Sam Francis featured in Individualités d’aujourd’hui, a group show of twenty-seven artists at Galerie Rive Droite, Paris. Situated not far from the Musée du Louvre, Galerie Rive Droite was uncompromising in its support of contemporary art. On this occasion its gallerist, Jean Larcade, gave over the white-walled space to the critic-theoretician Michel Tapié de Céleyran (fig.1), permitting him to concoct a provocative exhibition illustrating his radical vision for contemporary art. Tapié’s catalogue text pronounced the end of collectives and ‘isms’, whether centuries-old or more recent avant-garde movements such as cubism, fauvism and surrealism. He declared a new era for art some thirty years after dada’s incendiary anti-art actions and two catastrophic world wars had cleaned the slate: ‘with all the classicisms honourably installed in the museums, it’s our turn now to bring into being an art autre [art of another kind].’1

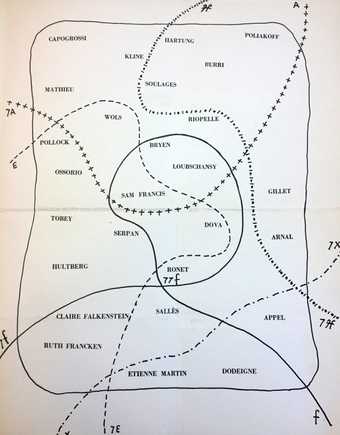

Fig.2

Page from Michel Tapié, Individualités d’aujourd’hui, exhibition catalogue, Galerie Rive Droite, Paris 1954

In this publication, a full-page drawing replaces the customary list of artists and works. Instead, the printed and capitalised names of the participants, from Karel Appel to Jackson Pollock to Wols, are distributed in clusters across a strangely partitioned space (fig.2).2 It resembles a map, with its routes and boundaries indicated by a variety of lines and its localities by the artists’ names. Some of the borders, drawn using broken lines, seem permeable; others less so, including the unbroken outer boundary in the form of a soft-cornered rectangle. The five inner dividing lines wander into and out of the rectangle, perversely evoking the elevations and gradients of an ordnance survey map. Each line is labelled: 7A, 7f, 7E, 7X. These mystifying indicators suggest mathematical set theory, a logical structuring system for relations between objects and sets or groups.3 But here, as laid out in the drawing, we seem to face a corrupted set field of asymmetrical vectors, omitted values and random variables. Functional notation has turned into a dada diagram, reminding us that in mathematics, as in topography, art or language, concepts and symbols are only rendered consistent and usable through accepted convention.

In the diagram the name ‘Sam Francis’ is centrally located, alone, but in close proximity to those of poet-painter Camille Bryen and abstract-surrealist Marcelle Loubchansky above, and Italian artist Gianni Dova below. Also below is Prague-born biologist and surrealist associate Iaroslav Serpan, who holds his own in the company of a troupe of Americans: Pollock, Mark Tobey and John Hultberg, plus the influential painter and art brut collector Alfonso Ossorio. Other names cluster at the sides and corners: the quartet of abstract artists consisting of Hans Hartung, Pierre Soulages, Serge Poliakoff and Alberto Burri, and a trio comprising Georges Mathieu, Franz Kline and the ‘Spazialismo’ artist Giuseppe Capogrossi. This is an artistic topology configured like a deformed, two-dimensional Möbius strip in continuous movement, each name spatially separated but dynamically connected to every other name and point. Some of the personalities seem aptly coupled – the sculptors Eugène Dodeigne and Étienne Martin at the lower edge; close colleagues Hartung and Soulages; or the two women artists Claire Falkenstein and Ruth Francken at lower left. Others force a pause: should the materialist works of Burri really join forces with the flat-surfaced geometries of Poliakoff? Is the aristocratic French extrovert Mathieu a suitable companion for the reserved American Kline? Why is Jean-Paul Riopelle not situated nearest to Francis, given their very close friendship?

Moreover, in a Cold War world riven by the aftermath of conflict and destruction, political division, economic disparity and exile, and with artists from so many different countries – the US, Italy, France, Russia, Belgium, Germany, Canada, Holland, the Philippines – will everyone get along with each other? The disjunctions are national, stylistic and personal, but no matter: the Individualités map allows for travel between sectors, and for magnetic attractions and repulsions to coexist within an organic aesthetic ensemble. For in Tapié’s view, all of these artists were courageous conquistadors of an unknown terrain beyond the reach of tired-out genres and patriotic identifications. They had abandoned all reason and rationalism in favour of an original and forceful expression, retrieved from the primal depths of the self – the ‘imaginaire’ – and given material form in works that resembled the very birth of art through their improvised techniques, roughened surfaces, magma of pasty pigments, disordered line, and puddles and drips of acrid colour. As Tapié proclaimed it, this would be a truly ‘other’ language of art, incorporating the destruction of form in painting or sculpture into its resurrection as something else: abstract, ecstatic, explosive, vividly hued, shocking, non-figurative, boundless, bewildering, gestural, violent, lyrical, informel.

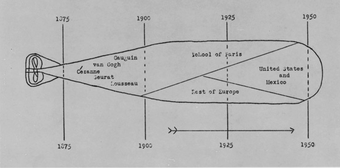

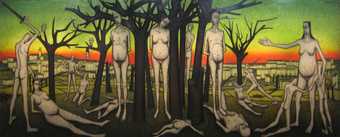

Fig.3

Alfred H. Barr Jr

Torpedo Diagram 1941

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Museum of Modern Art

Francis’s inclusion in Individualités d’aujourd’hui was not by happenstance. It indicates his centrality to an intricate network of aesthetic affinities, influences, exhibitions and social connections whose hub was Paris. In contrast to the torpedo diagram created in 1941 by Alfred H. Barr Jr, director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, in which he predicted that American and Mexican modern art would be at the forefront of world art developments by 1950 (fig.3), both Tapié’s novel map and the present essay plot Francis’s position in the French and European milieu of lyrical abstract painting, also known by the art critical terms informel and art autre. This essay explains the importance of Paris as a social nexus of ‘discourse’ about painting – as Francis’s close friend, the philosopher and art critic Rachel Jacobs, put it – in the development of Francis’s abstract painting and its reputation up to and at the time that he first worked on Around the Blues 1957, 1962–3 (Tate T00634).4 In particular, the essay focuses on the promotion of Francis’s paintings by Tapié and the art historian Georges Duthuit in order to highlight the significance of existentialist and phenomenological philosophy, and post-war surrealism, to the reception and interpretation of Francis’s paintings, including by the artist himself. In Francis’s painting, culminating with the group of large-scale works that includes Around the Blues, as well as In Lovely Blueness (No.1) 1955–7 (Centre Pompidou, Paris), In Lovely Blueness (No.2) 1955–6 (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago) and the Basel Mural (Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; and private collection, California), we find a lyrical and subjective mode of abstraction whose heritage is located in the legacies of surrealism and impressionism. Viewing Francis’s paintings of the 1950s through this alternative lens for the first time, this essay provides a refigured understanding of Francis’s ‘American’ and abstract expressionist identity, and of gestural abstract painting more broadly as an international style.

Creative networks

After graduating from the University of California, Francis chose to move to Paris rather than New York or San Francisco, arriving with fellow artist Muriel Goodwin in October 1950. In a matter of a few years Francis distinguished himself as an up-and-coming painter in the cultural ‘colony’ of Americans in Paris.5 Far from being isolated in his studio or limited to a coterie of compatriots for company, he was a lively bilingual participant in an ever-expanding Paris-based constellation of abstract artists, writers, art critics, curators and collectors.6 Within this nuanced social art world, each artist asserted the singularity of their work while depending upon the artistic, social and material infrastructure of a community of painting. This community was both local and quotidian, on the one hand, and on the other, globally networked through personal friendships and professional links, gallery contracts and publicity strategies, public commissions and private obligations, all mediated by larger geopolitical and economic forces. By 1957, when Around the Blues was painted in Mexico City, Francis had achieved significant public and critical attention as a major artist in the international rise of gesturally expressive, lyrical or informel abstraction.7

Much of the scholarship to date on Francis evinces confusion about his relationship to French art, matched by the uncertainty about what constitutes the ‘French tradition’ and the École de Paris.8 For conservative nationalists, the French tradition was built upon classical foundations and an idealised figuration; for modernist defenders of the École de Paris, it implied a synthesis of fauvist colour and cubist space; for partisans of the Communist Party, it could only reside in the revolutionary realism of Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) and Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), aided by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). Alternatively, Francis has been viewed as alone among the Americans to profit from the ‘Watteau to Matisse tradition of hedonism’, according to critic and curator Priscilla Colt in a 1962 essay on Francis.9 Here Colt evokes a French tradition defined by its sensual colourism and its alluring, erotic and decorative visual appeal. To diminish his involvement with contemporary Parisian painting, art historian William Agee points out the contrast between Francis’s aqueous paintwork and the ‘thick art brut surfaces’ of Mathieu, Soulages, Jean Dubuffet and Jean Fautrier (four quite distinct artists).10 These artists were, however, as concerned as Francis with painterly questions of surface unity, the unravelling of form and sensual material exploitation, and with the intellectual premises of their chosen medium. They each proclaimed their dedication to a tradition of painting, to what Francis described as ‘la vraie peinture’ (‘true painting’).11 For Francis at least – as for many of his friends and colleagues – this was both an ancient artistic culture and a tradition in the making, an abstract ‘tradition of the new’, to use critic Harold Rosenberg’s phrase.12

In early letters home, Francis expressed disdain for the work of young French artists as compared to his Bay Area colleagues.13 But he was pleased to write to his father and stepmother in late 1950:

Good news. I have had, already, one of my paintings accepted for the big Winter Salon at the Paris Museum of Modern Art [Salon de l’art libre]. Here it will be on view with paintings from all over the world, including the best in the U.S., England and of course Paris. I am lucky I guess, at any rate my paintings here so far have had quite an effect on all who have seen them, including the judges of the Salon.14

The salon system was (and is) a long-standing institutional feature of the art world in France, a year-long calendar of large-scale exhibitions visited by an enormous public – some with juried entry or by invitation, others open to all. Several new salons were founded at the end of the Second World War to prioritise modernist art, including the Salon de mai in 1945 and the Salon de l’art libre in 1947. The Salon des réalités nouvelles advertised its wholly abstract and international remit from its inception in 1946, orienting towards geometric neo-plasticism and constructivist abstraction that, in American artist Ralph Coburn’s recollection, ‘emphasised colour and more or less systematic picture-building’.15 Francis was especially boosted by the invitation to show at the more eclectic Salon de mai at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris: ‘This is the best and most coveted show in Europe … So I’m lucky again. But not money lucky as this is strictly a prestige show and works are not for sale.’16

Fig.4

Jean-Paul Riopelle

Trellis 1952

Watercolour on paper

318 x 406 mm

Tate T00084

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

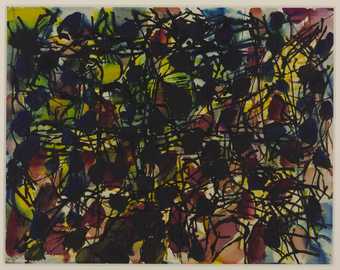

The lack of financial reward aside, the Salon de mai played a role in connecting Francis to the Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle. Riopelle was a dynamic figure in the ferment of critical debate and exhibitions around abstract art and surrealism from which informel and lyrical abstraction emerged. In summer 1947 Riopelle made an immediate impact with watercolours shown in an exhibition of four Canadian painters titled Les Automatistes at Galerie du Luxembourg. He signed the surrealist protest tract Rupture Inaugurale, issued on 21 June 1947; participated in the International Exhibition of Surrealism at Galerie Maeght (July 1947); and supplied illustrations for the January 1948 issue of a new surrealist journal, Néon. In December 1947 Riopelle also joined a cluster of artists brought together by Mathieu and Bryen at Galerie du Luxembourg in an exhibition titled L’Imaginaire, where ‘abstraction lyrique’ (lyrical abstraction) was announced as a new and distinct development.17 In 1949 Riopelle’s solo show at the surrealist-affiliated Galerie Nina Dausset was introduced by Benjamin Péret, André Breton and Elisa Breton in a collective automatist text lauding his vividly hued, black-lashed compositions (see, for instance, Trellis 1952; fig.4). These small, gestural works were praised as the doorways to a liberated and multi-sensorial environment, wherein ‘the aurora borealis, this trembling of a cloud, is without any doubt beginning her rowdy dance with legs aflame and flowering skirts. She will soon dominate the whole scene where Riopelle lives like the screech of a gull.’18

The avant-garde legacy of interwar surrealism and its revived vital force in the post-war period provided a primary model for a liberated and lyrical artistic expression. Some thirty years after its revolutionary inception in automatic writing and drawing by the likes of Breton, Philippe Soupault, Joan Miró and André Masson, psychic automatism retained its emancipatory potential. Automatist procedures promised the extraction of authentic dream images and unfettered emotive force from the mind’s inner depths, expressed in new kinds of ambiguous pictorial space, spontaneous gesture and chance procedures that were decoupled from conscious intention and technique. But automatism was also harshly critiqued for the ease with which it could become static and decline into ‘conceptual mechanisms’, as Riopelle put it in a sequence of short texts questioning automatist practice in the rebel journal Rixes.19

Fig.5

Sam Francis

Untitled 1946

Private collection

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

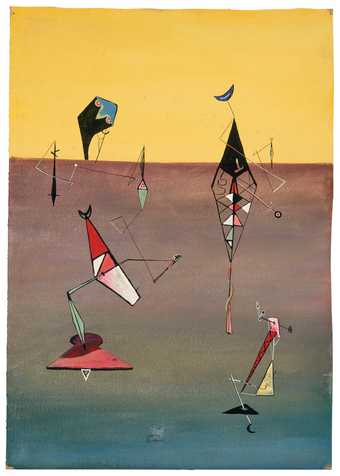

Fig.6

Simon Hantaï

Fleurs d’amants, No.69 1954

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© Archives Simon Hantaï/ADAGP, Paris

Photo © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist. RMN-GP

A condemnatory verdict of surrealist failure was not rendered without a prolonged working-through of the issues in public and private debate, methodological and technical experimentation, and self-interrogation. Francis was not exempt from this process, which commenced before his work in Paris and is plainly evident in canvases of 1946, such as Untitled (fig.5). Here Francis’s open debts to Yves Tanguy, Miró and Giorgio de Chirico testify to the significant surrealist presence in the Bay Area during the 1940s.20 In Paris, fellow Americans Ellsworth Kelly and Ralph Coburn, and those close to Francis such as Riopelle and the Hungarian émigré Simon Hantaï (see, for example, Fleurs d’amants, No.69 1954; fig.6), actively engaged with surrealism’s principles, theories and creative resources in order to identify their own route forwards – in each case, towards anti-compositional modes of abstraction.21 Expanded criteria, techniques and results were sought, and the loosening of the strictures of psychic automatism and its transformation into a broader credo of immediacy and spontaneity was presciently observed by critic Léon Degand in his catalogue preface for Les Automatistes:

Automatism? To be exact: an advantageous submission to the demands of spontaneity, to pictorial insubordination, to chance in the use of technique, to romanticism of the brush, and to an overflowing of lyricism.22

Fig.7

Sam Francis and Georges Duthuit at a café in Paris, c.1952–3

Sam Francis Foundation, California

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

When Francis met Riopelle at the Salon de mai in spring 1951, Riopelle had retained his extensive network of surrealist-affiliated colleagues and contacts. Francis was introduced to Pierre Loeb, dealer of Miró, who admired Francis’s paintings in a studio visit but refrained from taking him on at his gallery. The enterprising gallerist Nina Dausset took the risk and proposed a solo exhibition at her bookshop-gallery space on rue du Dragon for February 1952.23 In October 1951, Francis’s father and stepmother were informed by Francis that he had decided to stay on in Paris, with not just one but two solo gallery shows on the schedule – ‘unheard of good luck for a young American in Paris’ – and growing critical enthusiasm for his work.24 Most importantly, new friends and supporters included the influential poet Henri Michaux, who aided Dausset in the choice of works for the show;25 the hyper-active critic-curator Tapié, who quickly introduced Francis into the exhibitions and publications he organised to promote art autre; the surrealist writer Patrick Waldberg; and the art historian and editor Georges Duthuit. Son-in-law of artist Henri Matisse and a scholar of Byzantine art and fauvism, Duthuit was described by Breton in 1942 as among the ‘most lucid and daring minds’ of the time.26 From 1948 to 1950 Duthuit was chief editor of the bilingual literary magazine Transition and became an intimate intellectual interlocutor of the Irish playwright, art writer and translator Samuel Beckett; Francis would attend the opening night of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot at the Théâtre de Babylone in Paris on 5 January 1953. An important supporter of Riopelle as well as Pierre Tal-Coat, Nicolas de Staël and Bram van Velde, Duthuit was also closely connected to the English modern art scene, including eminent figures such as writer and Bloomsbury salon hostess Mary Hutchinson and critic Herbert Read.27 Charismatic and erudite, Duthuit would become the most perceptive French interpreter and behind-the-scenes publicist of Francis’s work, as well as a pivotal figure in his social life and artistic thinking during these early years in Paris (fig.7).28

Exhibiting nothingness

Fig.8

Installation view of Sam Francis’s 1952 exhibition at Galerie Nina Dausset, Paris, with Turquoise and Pink (centre) and Composition in Pink (right), both c.1949–50

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

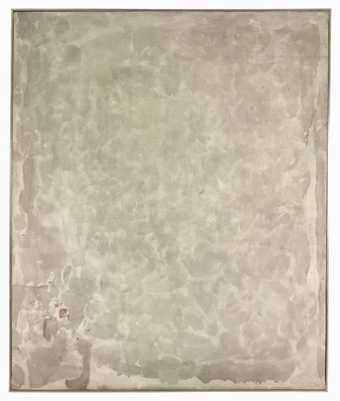

Fig.9

Sam Francis

White 1952

Oil on canvas

2021.8 x 1684 mm

Private collection, Cologne

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Installed at Nina Dausset’s small gallery in February 1952, Francis’s vaporous white, pinkish and red-hued canvases shocked even experienced viewers of the most contemporary abstract painting, to judge by reviews and recollections (fig.8). Franz Meyer testified to ‘stupefaction’ and Duthuit recounted an ‘elementary epiphany’ on viewing ‘a pink canvas, extremely illuminating, trimmed by a large strip in gleaming black’.29 Their ecstatic responses were provoked by the vision of luminous colours pooling across a fluid pictorial space. The porous cellular screens of diluted pigments are so thinly brushed that the technique is one of staining and blotching rather than form-building composition or gestural signage. Despite the visible edges of canvas tacked to the chassis, this pictorial space lacked all perspectival indications, appearing to have no known dimensions or altitude. The centre is annihilated by the delicate all-over coverage of the paint, and the framing edge is virtually transgressed. Each painting in the exhibition presented an ambiguous and disorienting sense of space to the grounded, vertical viewer (such as White 1952; fig.9). Although dependent on photographs rather than first-hand experience of the exhibition, Fred Martin, Francis’s painter friend in San Francisco, wrote to Francis that ‘I gather that what I saw was almost exactly nothing’.30 It seems Francis had achieved the effect he had been working on leading up to the exhibition, which he described to his father and stepmother:

The paintings have become, since, much more cosmological in feeling and of much greater spatial expansion. Ambivalent spaces which seem to be bounded, yet unlimited. And also some that seem to be limited in a certain sense I can’t explain and yet unbounded by a frame.31

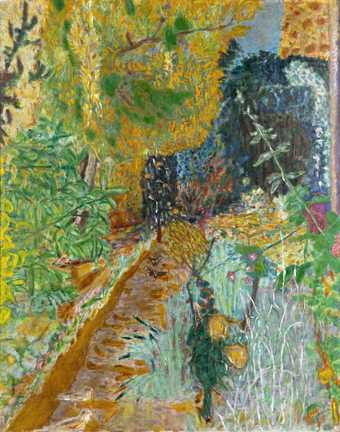

Fig.10

Pierre Bonnard

Le Jardin 1936–8

Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris

© Pierre Bonnard

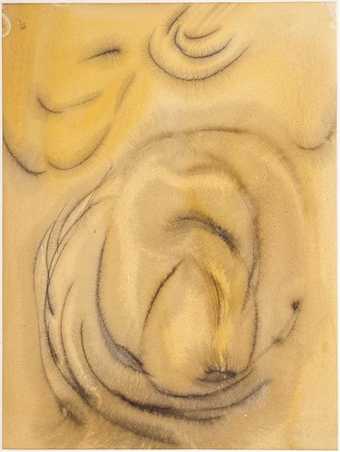

Fig.11

Henri Michaux

Figure Jaune 1948

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© ADAGP, Paris

Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Jean-Claude Planchet

Fig.12

Jack Youngerman

Rochetaillée 1953

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Critics turned to fantasies of intergalactic flight, with Jacques Peuchmaurd describing the ‘white’ paintings as ‘cluttered fog[s]’ and ‘interstellar’ spaces made of melted-down, ‘colourful masses’.32 Explanatory comparisons were found by Peuchmaurd in Pierre Bonnard’s sunlit scenes, where brilliantly coloured objects dissolve into the light (see Le Jardin 1936–8; fig.10) and Michaux’s watercolours that set legible figuration and solid form aside in a move against empirical fact (as seen in his Figure Jaune 1948; fig.11). Roger van Gindertael perceptively aligned Francis and Rothko, having looked at the latter in the exhibition Regards sur la peinture américaine at Galerie de France – a show that Francis also saw.33 Charles Estienne rightly pointed to Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) as an important precedent (perhaps without knowing that Francis examined Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White 1918 at MoMA in New York in 1950), before comparing Francis to his harder-edged, more geometric compatriot Jack Youngerman (see Rochetaillée 1953; fig.12), who was resident in Paris from 1947 to 1955 and whose work was on show at Galerie Denise René:

One could, and should, have serious reservations, from a plastic point of view, on the game being played by Sam Francis with the void; at least he must recognise the risk he takes and translate it pictorially; three or four quite fascinating paintings renew, after all, Malevich’s gesture, animating with almost nothing, with a wisp of grey or white touches, the canvas surface. But the risk is met head-on, and loyally pursued.34

The vertigo-inducing emptiness and absence of form in each of Francis’s canvases of ‘clotted fog’ (in Peuchmaurd’s words) seem to have been this threat or risk, or as Gindertael describes it, ‘an extreme adventure’.35 Constructed space and depth have become a vertiginous abyss into which the viewer might fall, where colour becomes inseparable from non-colour, and the painting’s very existence runs the risk of its own negation.

The risk was that this blatant presentation of formless emptiness, of nothing but a bubbled skin of paint, would prove too much of a danger to the integrity of both artwork and viewer. How could a sense of self remain when the object charged with mediating between the human subject and its worldly surround becomes an image of nothing? Such an encounter with the unknown, the formless and nothingness had been the topic of Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophical novel La Nausée (Nausea) (1938). Human existence – the question of how one dwells in the world, in philosopher Martin Heidegger’s terms – is described by Sartre as a dreadful confrontation with an abundant, obscene nature and with objects whose identity has ‘melted, leaving soft, monstrous masses, in disorder’.36 Made of viscous muck, painting is but formless decor in the frightening stage-set of existence, full of superfluous but unavoidable and irreducible things and amorphous experiences. For many observers, informel abstraction confirmed this existential worldview. Tapié drew directly upon Sartre’s nauseous vision, along with eighteenth-century physicist Isaac Newton’s theory that inert matter possesses its own innate force, in his short preface for the exhibition White and Black at the Galerie des Deux Îles in July 1948. The show included Jean Arp, Bryen, Fautrier, Jacques Germain, Hartung, Mathieu, Francis Picabia, Tapié, Raoul Ubac and Wols, and was one of several events held at the time in which definitions of lyrical abstraction were in play. In his preface the critic riffs on the artworks as an abject revelation of ‘realities’ multiplying and swarming like ants, absorbing all possible notions of rhythm, style and composition.37

In 1950 Sartre was at the top of Francis’s reading list, while Heidegger was highly recommended by Fred Martin as he consulted with Francis over the ‘value of un-form in shaping certain of the directions of contemporary art’.38 Making what seems to be a direct connection to the ‘almost exactly nothing’ that he saw in the photographs of Francis’s paintings, in a 1953 essay Martin advocated beginning

to hunt the lair of value in the land of chaos … If value perhaps be not caught in form, there is only one other place to look and that is in the deeps of chaos, deeps where all are one, where, if value be at all, value is everywhere. Then value would be in the matter of pictures, it would be in the nothing of this thingness, in the un-form of their form.39

Martin suggests here that a hostile war with a chaotic world of un-formed things, as Sartre described it, is not the only option. In the phenomenological thinking of Sartre’s colleague Maurice Merleau-Ponty, being in the world is envisioned as significantly less alienated and sickening. Instead, human existence is described as embodied immersion in a densely woven, vibrating flux of multi-sensorial experience. In his essay ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’ (1945), Merleau-Ponty argues that a painting assumes its place in the world as an expression of the whole, as a coloured material emblem of ‘the unsurpassable plenitude which is for us the definition of the real’.40 This definition of the real does not rely upon empirical data or objective scientific thinking. Paul Cézanne, above all, but also de Staël, Paul Klee, Alberto Giacometti, Matisse and Germaine Richier, serve as illustrations for Merleau-Ponty of the lesson that perception and sensation, interior and exterior, the actual and the imaginary are inseparable from each other. Artists, and especially painters, are privileged as seers for whom vision was never simply an inventory of the visible: a painting, writes Merleau-Ponty, ‘offers the gaze traces of vision, from the inside, in order that it may espouse them; it gives vision that which clothes it within, the imaginary texture of the real’.41

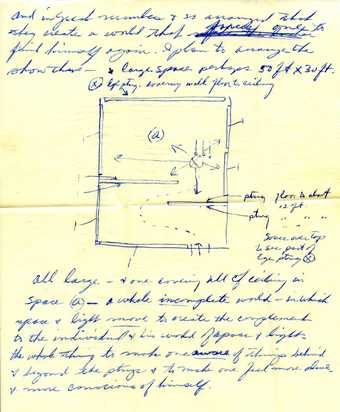

Fig.13

Sam Francis, page from a letter to ‘Dad and Virginia’, 24 August 1952

Sam Francis Foundation, California

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

In letters home Francis evoked this kind of expanded field of painting as the enlightening mediator between exterior eyesight and revelatory insight: ‘I feel that painting must put me in a position of doubt! Can you envisage a painting of no dimension?’42 Each painting becomes, in this idealist view, a potential passageway to an immersive world in which our spatial existence becomes more than merely physical. Francis describes larger paintings that demand more space to breathe, ‘and in great numbers and so arranged that they create a world that forces one to find himself again’ (fig.13):

All large, and one covering all of the ceiling in space (a) – a whole incomplete world – in which space and light move to create the complements to the individual and his world of space and light, the whole thing to make one aware of things behind and beyond the paintings and to make one feel more alive and more conscious of himself.43

Fig.14

Sam Francis in front of the second state of Deep Orange and Black 1953–5 at his exhibition at Galerie Rive Droite, Paris, 1955

Artwork © Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Photo © Pierre Boulat

Studio views show how Francis clustered and layered paintings in progress, enlarging them as much as he could based on how much paint and canvas he could afford, such that an enveloping, cloud-like environment would enclose the artist and the canvases’ viewers. The painting as background and surround is further emphasised in portraits of the artist and his friends, where the border of the work cannot be seen, as is the case in Pierre Boulat’s photograph of Francis in front of Deep Orange and Black (Kunstmuseum, Basel) after he had reworked it in 1955 (fig.14). Collectors sought to re-create this absorptive effect in their home displays. Mary Hutchinson imagined placing a statue by Giacometti next to her Francis canvas White 1952 (see fig.9) in her London home in order to capture ‘the essence of man and the mysterious elemental world in which he tremulously moves!’44

Indeterminate space: Tapié and Duthuit

Fig.15

Sam Francis

Red–I 1950–1

Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.16

Sam Francis

Blue Composition c.1952

Private collection

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.17

Iaroslav Serpan

Saadestakso 1956

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Francis and so many other writers, artists, architects and philosophers sought to design a new kind of boundary-free space for the post-war epoch, and a new key to open it. For Michel Tapié, instead of form defining space, space produces form through a magical and infinitely indeterminate network of energy forces. With the exhibitions Véhémences confrontés at Galerie Nina Dausset in February 1951 and Signifiants de l’Informel I and II at Studio Paul Facchetti in November 1951 and June 1952, followed by the manifesto show Un art autre in December 1952 (also at Studio Paul Facchetti) and its accompanying book, Tapié sought to evidence his claims for an ‘other’ kind of art.45 In the paintings of Bryen, Francis, Serpan and Pollock, and the sculptures of Falkenstein, he saw the emergence of a boundless and indeterminate spatial cosmos as the habitation for a new kind of human existence governed by individual temperament rather than collective will.46 A grey painting by Francis was featured in the second instalment of Signifiants de l’Informel in June 1952, though it is not known which one. He had two paintings exhibited and given full-page illustrations in the catalogue-book for Un art autre – Red–I 1950–1 (fig.15) and Peinture (now titled Blue Composition, also described by Francis as Sea Surface Full of Clouds) c.1952 (fig.16) – and three paintings appeared in Tapié’s abstraction show Opposing Forces at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London in January – February 1953.47 Tapié next identified Francis as an exponent of lyrical abstraction in Premier Bilan de l’art actuel, 1937–1953, an important illustrated survey of contemporary art edited by surrealist affiliate Robert Lebel and published in May 1953.48 Here Francis’s liquefied voids were joined by Serpan’s complex calligraphic structures (such as Saadestakso 1956; fig.17) in the ‘lucid elaboration of new worlds, rethought at the level of the most current abstract ideas’.49

Fig.18

Claire Falkenstein

Sun c.1954

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

Fig.19

Camille Bryen

Usher 1953

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes, Rennes

© ADAGP, Paris

Photo © MBA, Rennes, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Louis Deschamps

Lest it be viewed as atavistic or naïve myth-making, Tapié’s terminology and conceptual apparatus for art autre drew upon modern science and mathematics: names cited include Stéphane Lupasco, author of Logique et Contradiction (1947) and theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, best known for the ‘uncertainty principle’ (1927). Above all, Tapié refers to mathematician Georg Cantor, inventor of set theory as well as the ‘Cantor space’ – a topological conception of space that likens it to distorted trefoil (three-part) knots: connected, compact, stretched, crumpled and continuous. The contrasting paintings of Serpan and Francis, and Falkenstein’s convoluted wire structures (see, for instance, Sun c.1954; fig.18), are taken by Tapié to exemplify this new topology: a deformed, infinite space distinguished by its capacity to act as a matrix for the production of new and contradictory kinds of abstract form.50 Art historically, Tapié called upon a dada lineage of avant-garde scorn for past subjects and techniques, hailing Marcel Duchamp and Picabia as iconoclastic forbears and crediting Bryen’s desire to see the total abjection of form (see, for instance, Usher 1953; fig.19).51 The writings of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) and the Spanish monk and mystic St John of the Cross (1542–1591) then join forces to combat the insidious corruption of writers and philosophers such as Plato (5th–4th century BC), St Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) and Boileau (Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux; 1636–1711) in Tapié’s melting-pot theorisation of art autre as the path to total becoming.52

Fig.20

Georges Mathieu

Un Silence de Guibert de Nogent 1951

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© ADAGP, Paris

Fig.21

Sam Francis

Deep Orange and Black 1953–5

Kunstmuseum, Basel

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

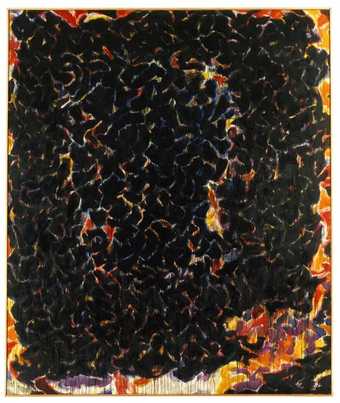

This daunting new world of chaotic infinity was given further elaboration in the small but important group exhibition Tendances actuelles, held at the Kunsthalle Bern in January 1955 and featuring the work of Francis, Bryen, Mathieu, Tobey, Michaux, Pollock, Riopelle and Tancredi Parmeggiani. Here the ‘authentic adventure’ is divided into two zones: sign and space (or void).53 Pollock’s ‘complex metagraphies’ (a term used to describe the synthesis of poetry or text with the pictorial or plastic dimension of painting) and Mathieu’s theatrical scripts (see Un Silence de Guibert de Nogent 1951; fig.20) are confronted with the ‘almost void’ [‘presque vide’] and ‘the non-sign without equivocation’ [‘le non-signe sans équivoque’] of Francis.54 Tapié’s introduction to Francis’s June 1956 solo show at Galerie Rive Droite affirmed his admiration for the ‘power of a spatial mystique’ (which he links to Claude Monet and Mark Tobey) and the terrifying glory of ‘contradiction’ in Francis’s latest paintings, such as Deep Orange and Black 1953–5 (fig.21).55

Because of his importance to Tapié’s conception of an art autre, Francis was not invited by Charles Estienne to join the group of artists who constituted the Salon d’Octobre in 1952, a venue for lyrical, expressive abstraction. Nor was he associated with the gallery À L’Etoile scellée, founded in 1952 by Sophie Babet and supported by André Breton, though he met the surrealist leader in early 1953 and was received favourably by Estienne and other surrealist fellow-travellers.56 He distanced himself from the often tendentious debates over the primacy of terms, whether informel, art autre or the related ‘tachisme’, and balked at Tapié’s attempt to create an École du Pacifique by corralling together Francis, Tobey, Falkenstein and any other West Coast American abstract artists in Paris.57 If Tapié poured scorn on Estienne publicly for his attempt to make tachisme (from tache, the stain, splash or splotch) the ‘zero degree of the birth of the work’, Dubuffet personally complained to Tapié about his forced inclusion in such a nebulous soup as informel, while Francis’s close friend Rachel Jacobs enquired: ‘And why should contemporary painting be called informel? Why cannot one see what is before one’s eyes?’58 Often the labels had little lasting relevance. Francis was co-opted into Groupe 54, which had a show at Studio Paul Facchetti curated by critic Pierre Restany to mark the latter’s own short-lived claim on the territory of lyrical abstraction. Francis was likewise incorporated into Julien Alvard’s nuagisme (cloudism) schema for abstract painting, with only marginally more success.59

Fig.22

Marcelle Loubchansky

Red Flow 1956

Israel Museum, Jerusalem

© Estate of Marcelle Loubchansky

Additionally, paintings by Francis featured in several independent ventures on the margins of surrealism. Red–I (see fig.15) was illustrated in the tenth issue of Meta (1953), a German magazine of experimental art and poetry edited by informel artist Karl-Otto Götz that featured writers and artists formerly associated with the CoBrA group and surrealism.60 Francis was also listed as a participant in Phases, a large and eclectic exhibition at Galerie R. Creuze in spring 1955 that was aligned with poet and art critic Édouard Jaguer’s group of the same name and its important journal.61 In line with these noteworthy links to a broad para-surrealist milieu, Francis’s work demonstrates visual affinities with Parisian contemporaries such as Marcelle Loubchansky (see Red Flow 1956; fig.22), whose paintings were described by Breton as a revelatory vision of the ‘true light of day’.62 Loubchansky showed at À L’Etoile scellée, Galerie Rive Droite, and with Francis’s subsequent dealer Jean Fournier at Galerie Kléber. Her fluid, organic and vividly coloured abstractions, with their violent intrusions, deserve attention alongside Francis’s indeterminate illusions of atmospheric depth in mottled colour, some marked with non-depictive, seemingly errant brushlines.

Fig.23

Jean-Paul Riopelle

Perspectives 1956

Tate T00123

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Fig.24

Andre Masson

Gouffre 1955

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© ADAGP, Paris

Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist. RMN-GP

Fig.25

Nicolas de Staël

Rue Gauget 1949

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Fig.26

Bram van Velde

Untitled 1951

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

© ADAGP, Paris

Fig.27

Pierre Tal-Coat

Passage au Pied de La Combe 1955–6

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© ADAGP, Paris

Moreover, Francis’s paintings sat well among the artists favoured by Duthuit, himself close to many of the surrealists. First and foremost is Riopelle, whose work, like Francis’s, features spatial expansiveness and organic evocations – although Francis stayed away from his friend’s penchant for thick, glossy impasto laid on with a palette knife in overlapping tiles to induce a jarring chromatic vibration (see, for instance Riopelle’s Perspectives 1956; fig.23). Affinities may be drawn between Francis and the cosmic skyscapes of former surrealist André Masson, whom Francis met in summer 1951 and who followed Chinese aesthetics in advocating the ‘inner emptiness’ within oneself prior to the act of painting in works like Gouffre 1955 (fig.24).63 Duthuit lauded de Staël’s thickly painted compositions, which the critic and poet René de Solier praised in 1950 for ‘transforming the notion of abstract art through relentless effort, careful to establish the rectitude of the fragmentation so as to open up a new space’ (see de Staël’s Rue Gauget 1949; fig.25).64 Samuel Beckett and Duthuit exchanged passionate letters and conversations about the luridly coloured, stymied labyrinths of Bram van Velde, whose most recent work Francis saw at Galerie Maeght in March 1952, and who visited Francis’s studio in mid-1953 (see van Velde’s Untitled 1951; fig.26).65 Pierre Tal-Coat’s evanescent ‘landscapes’ and ‘vipers’ nests of space’, such as Passage au Pied de La Combe 1955–6 (fig.27), stirred a similar intensity of feeling.66 Duthuit wrote to Beckett in 1949, relaying a conversation between Masson and Tal-Coat: ‘they claim that, rather than putting down forms, they are setting them free from one another, creating between them zones of silence, fields of non-movement … On the edge of this void stands a sign, a value just set there that offers a key to it, opens it up, breathes life into it.’67

Fig.28

Sam Francis

Green and Red 1950

Private collection, France

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

In July 1953, not long after Francis’s work was shown in London in Opposing Forces, Duthuit alerted an Anglophone audience to a new politics of abstraction in Paris: a modern aesthetic tradition based in colour and optimism (compared to literature’s nauseous or socialist realism), of whom the ‘most ardent advocates, even in Paris, [are] other young Americans’ such as Riopelle and Francis.68 Duthuit’s essay on Francis, Tal-Coat, Riopelle and van Velde had just appeared in Lebel’s Premier Bilan de l’art actuel, positioned after Tapié’s text and countering his idea of explosive action as utter expression. The title of Duthuit’s essay – ‘The Animators of Silence’ – seemingly alludes to Merleau-Ponty’s observation that ‘the idea of complete expression is nonsensical, and that all language is indirect or allusive – that it is, if you wish, silence’.69 After short sections on paintings by Tal-Coat, van Velde and Riopelle, Duthuit dedicated a third or more of his discussion to Francis, accompanied by a full-page illustration of Green and Red 1950 (fig.28). This section of his text was translated from French to English by Beckett. Titled ‘Sam Francis: Animator of Silence’, the piece was sent by Duthuit to Mary Hutchinson in London in search of a publication venue. Hutchinson offered it to the editors of Nimbus: A Magazine of Literature, the Arts, and New Ideas, a new London-based literary journal whose name corresponds serendipitously to the giant, thickly layered, dark grey rain cloud that appears to dominate works such as Green and Red.70

Duthuit rapturously describes Francis’s work as an otherworldly art, whose ‘shrouds of mist’ offer little visual nourishment, whether through emphatic paintwork or ‘verbose’ expression, but rather present ‘a solution of nebulae permeated with the palest honey … a snowy sherbet tinged with rose … the plenitude of emptiness … the air itself.71 Such ‘a painting of depth, a depth against which we are freely allowed to detach ourselves’,72 issues an invitation to the viewer to attend a reconciling encounter:

It is by penetrating to the heart of such emotions, and not by the sedulous transcription of the circumstances which call them forth, that the painter rediscovers the fundamental and precious harmony by which we are related to the world of objects and enabled to bridge the gulf between our inner universe and that other which surrounds us.73

Duthuit’s poetic prose seeks to usher the viewer across the threshold of the painting to a ‘place made for the purified soul’.74 His dream of a reunified world is matched by Francis’s intention to create ‘A kind of Universe or world that seems to have formed by its own laws. Not touched by human hands. Yet there for the human eye – not the gods [sic] eye – for in a way it is the eye of the gods. A kind of window to look out of – not into.’75 Furthermore, in describing the paintings as the custodians of a numinous realm of spiritual plenitude, Francis’s and Duthuit’s conception of the artwork is one shared by the influential philosopher Gaston Bachelard: painting is the material and visual catalyst for a poetic revelation of the world reunified with the self. Francis’s luminous pictorial fields of cloudy air and water (the two most metamorphological substances, as described by Bachelard in his books on the elements) double as shimmering reflective mirrors to access a hitherto invisible, celestial realm.76 These are painted images containing neither objects nor content, but prompting a ‘gentle exaltation of ravellings’ from which the viewer will obtain ‘a maximum of freedom and satisfaction’.77

Reviving Monet, Seurat and Matisse

Fig.29

Claude Monet

The Water Lilies: The Two Willows, from the Nymphéas series 1915–26

Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris

© RMN (Musée de l’Orangerie)/Michel Urtado

Towards the conclusion of his 1955 catalogue essay for Francis’s solo show at Galerie Rive Droite, Duthuit addressed the question of how the painter achieves ‘a supremely beautiful impression with the limited means of which man disposes to incarnate it’. The critic reverted to an art historical mode to place Francis within a modern tradition of colour and light rather than figure and form: ‘[O]ne will have to pass through the experiences of Monet, then of Seurat and finally those of Matisse in order that all colours in Sam Francis’s canvases become what white formerly was in them: a simple and unique light-colour.’78 What was it about these modernist masters that was so important for Francis, such that he apparently claimed ‘I make the late Monet pure’?79 As Life magazine reported, Francis was not alone in paying a debt to Monet, seeing in his Nymphéas 1915–26 (fig.29) and other late works a painterly revision of light and shadow – chromatically shivering in the dawn mists or flaming red and orange at sunset – that foretold of the coming of gestural abstraction.80

In the milieu of lyrical abstraction in France during the 1950s, Monet’s amorphous and imperfect world of colour was revivified as an original link in the chain of a mystical and Romantic tradition. This anti-formalist tradition is the antithesis of American critic Clement Greenberg’s theory that modernist painting should always aim to be devoid of references to the world beyond itself, focusing instead on visual self-sufficiency and optical autonomy.81 In 1953 Masson published his powerful evaluation of Monet as a creator of a pictorial world in which no one form has priority, contours or limits. Against notions of untamed informel expressionism, Masson insisted that the creation of this new world had nothing passive or random about it; it was a lesson in discipline and technique as the impressionist master organised the rhythms of colour and exploited myriad kinds of touch and texture. Above all, for Masson, as for Duthuit and Francis, Monet’s work exposed the false dichotomy between the unreal and the real, imparting a transparent interior vision of ‘new depths’ through an indeterminate, non-empirical view of nature.82

Fig.30

Sam Francis

In Lovely Blueness (No.2) 1955–6

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

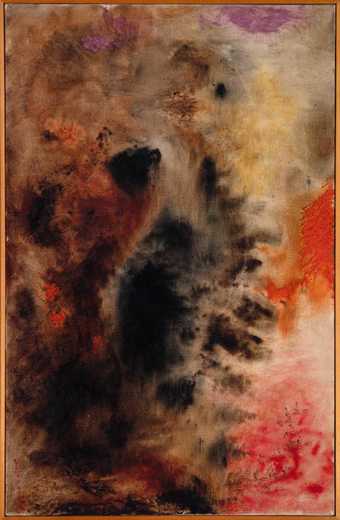

For Francis, indeed, the Nymphéas’s changeable colouration was ‘almost like the paintings of a blindman – and Monet was probably blind’.83 It was this kind of absorbing vision of a thickening rainbow surface, at once deep but shallow as a translucent scrim, that Francis coveted and sought to emulate. In 1956 Francis’s Galerie Rive Droite exhibition elicited this praise from critic Julien Alvard: ‘the monochrome sky screen of Sam Francis has become an open sky permitting every liberty to variations of light and colour’ (see, for instance, Francis’s In Lovely Blueness (No.2) 1955–6; fig.30). Alvard’s comments are equally appropriate to Around the Blues, in which Francis horizontally extends the colours and starts to burst open the cellular forms in blue, red and yellow, allowing increasing amounts of white space into the composition. Alvard extolled the way in which the ‘breath of impressionism, above all Monet’s, banishing all human presence from these canvases, is rediscovered here in its absolute pantheism, its irresistible appeal to the elements and the annihilation of man in nature.’84

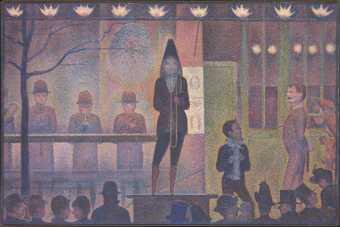

Fig.31

Georges Seurat

Parade de Cirque 1887–8

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The capacity to simultaneously divide the pictorial field into its chromatic parts and to reunify it into a ‘coloured exaltation’ of nature was a gift equally attributed to the neo-impressionist Georges Seurat (see his Parade de Cirque 1887–8; fig.31), although the revival of his legacy was a much less mainstream affair than that of Monet. For Duthuit, Seurat’s work provided the technical example of how to use the analysis of colour to achieve a true and undivided white: ‘that white unanimous strife’ produced by a colour spectrum disk when it rotates at high speed, or the ‘simple and unique light-colour’ achieved by Francis’s paintings.85 Here Duthuit takes part in the move to resituate Seurat away from his recuperation in the 1920s by adherents of a neo-classical and rationalist aesthetic, who were associated with a return-to-order worldview that was ‘reassuringly ordered [and] geometric’.86 For Breton in 1947, Seurat’s divisionist technique, which involved using tiny dabs of colour to produce a luminous effect, was understood as magically bringing together the ‘realms of sight and vision’ to transcend the mere transcription of ‘an impression upon a retina’ and create an illuminated depiction of real life in all its startling crystalline facets, passing through ‘all the filters of sensibility’. Such a poetic art, said Breton in a remarkable revision of neo-impressionism’s utopian potential for regenerating the synthesis of art and life, ‘proposes to fulfil the function of a nerve-ending whose connections with the other surrounding “points of fire” allows us to make our way back to the centre of its (our) desire’.87

Fig.32

Henri Matisse

The Red Studio 1911

Oil on canvas

1810 x 2191 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2019 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Finally, there was Matisse, the painter who in 1905 took divisionism and fused its rainbow specks into astonishing fields of continuous coloured pictorial space, each one seemingly larger than the next. Viewers testified to their visual shock in front of the expanded scale and radiantly coloured surfaces of Matisse’s paintings: from early reports of ‘optical trembling’ and ‘vertigo’, to the amazement of American artists such as Rothko, Robert Ryman, Frank Stella and Francis who encountered The Red Studio 1911 (fig.32) at MoMA after its acquisition in 1949.88 The formal achievement, and the gift to the artists that came after him, said Matisse in 1941, was to construct pictorial space as a harmonious totality through a ‘combination of forces constituting the canvas’.89 Matisse wanted painting to issue an invitation: ‘I try to ensure that it enters the viewer’s mind whole, after which its effect depends on the depth of its expression and that of the viewer’s mind.’ To this end, he unified interior and exterior into one flowing arena: ‘Space is the extent of [the viewer’s] mind.’90 The plenitude of Matisse’s colour (including black) and his amplified spatial planes provide the viewer with a cloudy yet light-struck ambience into which the self looks and finds itself. This is painting as a mirror reflecting interior vision rather than an imprint of the exterior; a strange two-way mirror of the kind that appears in Chinese mysticism or symbolist and surrealist poetry, that one must pass through in order to arrive in what Duthuit called ‘the fugitive lands of the imagination’.91

Fig.33

Joan Miró

La Sieste 1925

Centre Pompidou, Paris

© Successió Miró/ADAGP, Paris

Photo © Jean-François Tomasian – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist. RMN-GP

Returning the gift given by Matisse, whose paintings he was able to view up close thanks to Duthuit, Francis stated in 1988: ‘My paintings have always had this kind of space: it’s like a corridor or a mirror.’92 Francis’s delicately brushed and stained surfaces, with their fluctuating paint density and globular forms, suggest the transparent but simultaneously opaque depths of murky water or skyward nimbus clouds. Their empty patches of white ‘spread out like a tide infiltrating the marshes of a flat bay’, writes philosopher Jean-François Lyotard.93 Akin to the continuous spatial fields of Monet or Matisse, or Miró’s surrealist paintings of the 1920s, such as La Sieste 1925 (fig.33), the coloured brush-marked surface permits what art historian Charles Palermo describes in Miró as a ‘passage into something – yet not as a breach, not precisely as “penetration” – that the background evokes. The beholder’s access to the luminous depths of the canvas … evokes neither an empty space nor a resistant surface.’94 The viewer is invited to imaginatively immerse themselves, to float their body in a boundless and fluid sea of colour and light. In Merleau-Ponty’s words: ‘The superficial pellicle [skin] of the visible is only for my vision and for my body. But the depth beneath this surface contains my body and hence contains my vision.’95

Yet it is also important to recognise that even such open paintings as Around the Blues, with their large expanses of white, do not permit the viewer to pass unimpeded. The beholder is separated from the painting by its actual limits: its visible canvas weft and warp, its oil-sealed surface.96 The promised access to the beyond is controlled by Francis’s presentation of a translucent surface that is simultaneously opaque and resistant to entry. Duthuit notes of Francis’s evanescent, ‘hygrocosmic’ (humid and universal) environments that we are given a vision of the purelands – the celestial realms or abodes in Buddhist and Taoist religion and philosophy – as though glimpsed through an intermediary scrim or ‘dimmed pane’, where acidic colours can be seen ‘bespattering the foreground of the picture as though it were a pane of glass insuperably closed against them’.97

Painting and post-war utopia

Fig.34

Sam Francis

Big Orange 1954–5

The Broad, Los Angeles

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

In 1942 Breton named Duthuit as one of a select few who, in the darkest of times, were motivated by the ‘anxious desire … to furnish a prompt reply to the question: “What should one think of the postulate that ‘there is no society without a social myth’? In what measure can we choose or adopt, and impose, a myth fostering the society that we judge to be desirable?”’98 At the war’s end, this utopian question and the wish for an answer remained a vital concern in differing ways for surrealism, Duthuit and philosophy. Writing on Matisse in 1949, Duthuit described the painted and brilliantly coloured depiction of space as ‘a gathering of force or energy everywhere present’. He aligned this unified painterly space with the Byzantine representation of space in mosaics and architecture, regarding both as continuous, interconnected and luminous – an artistic structure that functions as a ‘living organism’ in a society that integrates the individual into a ‘unison with the community’.99 In stark comparison to Tapié’s characterisation of painters as egotistically dedicated only to individualistic self-expression, Duthuit sought a revitalised communal harmony in art. For Duthuit, the glimmering painted surface silently solicits self-reflection; a spiritual inner knowledge that inevitably leads to an understanding of the points of union an individual has with others and with the world. The desired rapturous experience of these oceans of colour (the list of titles of works in Francis’s 1956 exhibition are but those of colours, such as Big Orange 1954–5; fig.34) is that ‘the space of a picture is the one we actually breathe in’.100

Fig.35

Bernard Buffet

Les Pendus, Horreur de la Guerre 1954

Fonds de Dotation Bernard Buffet, Paris

© ADAGP, Paris

At the time that Duthuit was writing, barely five years after the end of the Second World War, this idealised world of unity seemed ever further away in what he described as a ‘Europe … falling apart’.101 This was still the case, if not more so, in the 1950s, as the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) worsened, the far right reasserted itself in French elections and Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Lyrical pictorial expression assumed a newly redemptive and critical power in this divisive and threatening setting, when the devastation of the recent past was all too proximate, and the future unknown. If Duthuit’s poetic prose suggests aesthetic retreat, the surrealists sought out new ‘spiritual weapons’, to use Breton’s term, in the militant defence of liberty and went on the attack against forms of socialist and miserabilist realism linked to reactionary politics on both left and right. For the surrealists, the artwork was not merely an objective representation or isolated expression, but a reciprocal poetic invitation to an encounter with an engaged beholder, capable of provoking thought, defending the mind against dogmatism and repression, and mobilising revolutionary action.102 In March 1956 the surrealist critic José Pierre published a sustained denunciation of the dour, miserabilist scenes depicted by artists like Bernard Buffet (see, for instance, Les Pendus, Horreur de la Guerre 1954; fig.35) and the depredations of the art market in the widely read newspaper Combat-Art. Pierre concluded his protest with the statement that: ‘If “lyrical abstraction” turns its back on miserabilism, it opens onto the great jungles of poetry and the marvellous, illegitimate daughter of the unexpected love-making of surrealism and abstraction.’ He cites Pollock, Simon Hantaï, François Arnal and Wolfgang Paalen as exemplars of this approach alongside Francis, who ‘unfurls the most luxurious furs’, while Loubchansky and Falkenstein ‘unveil “the green membranes of space”’.103

Fig.36

Rachel Jacobs in Sam Francis’s studio on rue Tiphaine, Paris, c.1953, standing in front of Grey (in progress) 1954, 1955 (The Broad, Los Angeles)

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

In a parallel homage, the former CoBrA artist and renegade communist Asger Jorn favourably compared Francis’s denial of action to the ‘pseudo-activity’ of ‘so-called action painting’. In Jorn’s view, Francis’s paintings revealed the artist’s vital struggle ‘to overcome the disgust of the present, the horror of the future’ so as to commit ‘the sacrilege of revealing the things that are locked away and sacred’.104 In her catalogue text for Francis’s third solo show at Galerie Rive Droite in June – July 1956, Rachel Jacobs (fig.36) detailed the potential for ‘psychic life’ within the presentation of coloured surfaces ‘neither tangible nor geometrical’. In turn, she asked ‘whether a mathematical angel might not also emerge from his infinite limitations to enter the divine fire?’ Francis’s paintings are again understood, this time by Jorn and Jacobs, to proffer a ‘new aesthesis, a new vision’, if only momentarily.105 In this eschatological drama, the beholder’s earthly experience is transcended, enabling them to surpass all divisions and be resurrected into an as yet unseen kind of weightless and inhuman being.106

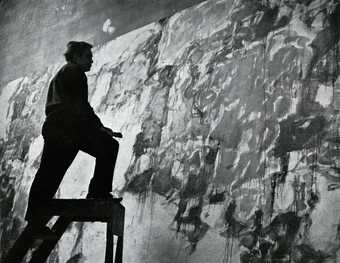

Fig.37

Sam Francis on a ladder in front of one of the Basel Mural canvases in his Arcueil studio, Paris, c.1958

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Photo: Georges Boisgontier

In early 1958, after a year of world travel, Francis wrote home to say he was ‘all gathered into myself back in mother Paris’.107 He worked incessantly to complete the ‘three huge sails’ of the Basel Mural triptych for their installation at the Kunsthalle Basel in April 1958, before beginning several major large paintings akin to Around the Blues, namely Round the World 1958–9, 1960 (Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel), Ahab 1958 (collection of Samuel and Ronnie Heyman, Palm Beach) and Meaningless Gesture 1958 (Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel).108 From 1957 onwards Francis exhibited regularly alongside Riopelle, Hantaï and Joan Mitchell at Galerie Jean Fournier and in 1961 the French state acquired Francis’s Composition Blue on White Ground 1960 (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes, Rennes) as part of its belated orientation towards the purchase of works by contemporary artists for the national collections.109 Nonetheless, by 1958–9, when Francis was included in MoMA’s touring exhibition The New American Painting, his transition to a new life as a distinctly American painter on the international art scene seemed irrevocable.110 Breaking from his usual silence, Francis wrote a short statement that was included in the catalogue for The New American Painting, beneath a dramatic photograph of the artist, paint brush in hand, stepping forwards on the top platform of a ladder as though climbing into the immense rippling surface of one of the three Basel Mural canvases (fig.37). It is a poignant and yearning text, replete with poetic symbolism:

What we want is to make something that fills utterly the sight and can’t be used to make life only bearable; if the painting till now was a way of making bearable the sight of the unbearable, the visible sumptuous, then let’s now strip away…all that.

These paintings lie under the cloud that soared over the inlaid sea.

Do you still lie dreaming under that huge canvas? Complete vision abandons the three-times-divided soul and its vapours; it is the cloud come over the inlaid sea. You can’t interpret the dream of the canvas for this dream is at the end of the hunt on the heavenly mountain – when nothing remains but the phoenix caught in the midst of lovely blueness...111

Francis recounts here a divine dream about painting and its role as an opening onto the celestial purelands of the spirit. Allusively, and without doubt deliberately, his reverie also tells another story, revealing the artistic depth and emotional and creative intensity of the years Francis lived and worked in Paris. The critical support he received from the abstract, philosophical and surrealist community of artists and writers, and the intellectual stimulation of the many long conversations with figures such as Duthuit, Jacobs and Riopelle, are painted in words into the enchanted coloured clouds of this dream, and deposited with each brushstroke onto the white gesso grounds of the In Lovely Blueness paintings, the Basel Mural and Around the Blues.