Ford and Empire

In 1983 the art historian Susan Beattie argued that Ford’s untimely death in 1901 ensured that his work happily predated the ‘unattractive Kiplingesque obsession with patriotism, health and “masculinity”’ that dominated much of British Edwardian culture. Beattie also claimed that Ford’s most explicitly imperial work – St George and the Dragon 1902 –‘failed disastrously’.1 In 1999, by contrast, the conservator Pip Laurenson characterised The Singer as a ‘fascinating document about the Victorian perception of other cultures subsumed under the notion of “Orientalism”’.2 What, therefore, were the imperial implications of Ford’s neo-Egyptian figures in the context of British involvement in Africa in the second half of the nineteenth century, and in relation to ideas of race current at the time?

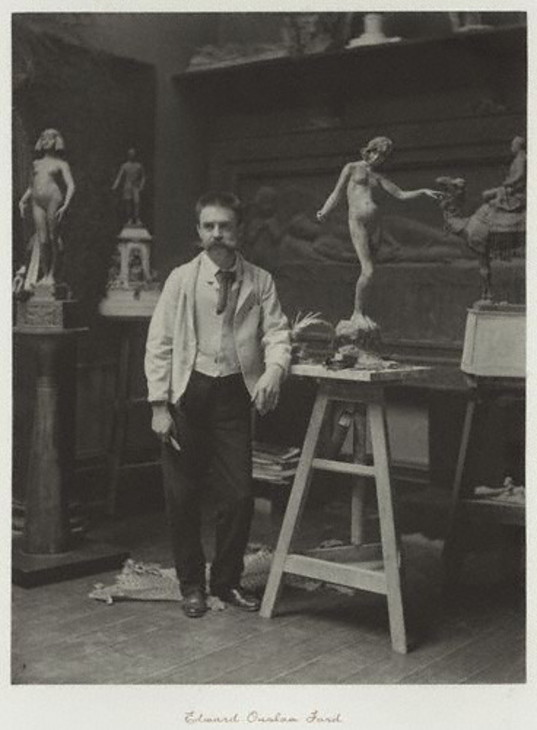

Ralph Robinson

Edward Onslow Ford in his Studio 1892

Platinum print

199 x 153 mm

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig.1

Ralph Robinson

Edward Onslow Ford in his Studio 1892

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The positioning of these two works at the same height in Ford’s studio serves as a reminder of the sculptor’s sustained professional investment in, and profit from British imperial markets and colonial conflict. With this in mind, it might be conceivable that The Singer and Applause, as representations of Egypt – a British imperial conquest of comparative success from the perspective of the late 1880s – sought to counterbalance the tragedy articulated by Ford’s General Gordon, particularly since Egypt and the Sudan were as adjacent on the imperial map as The Singer and General Gordon are in Robinson’s photograph of Ford’s studio.

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (side view)

Bronze, coloured resin paste and semi-precious stones

902 x 216 x 432 mm

Tate N01753

Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1894

Tate

Fig.2

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (side view)

Tate N01753

Tate

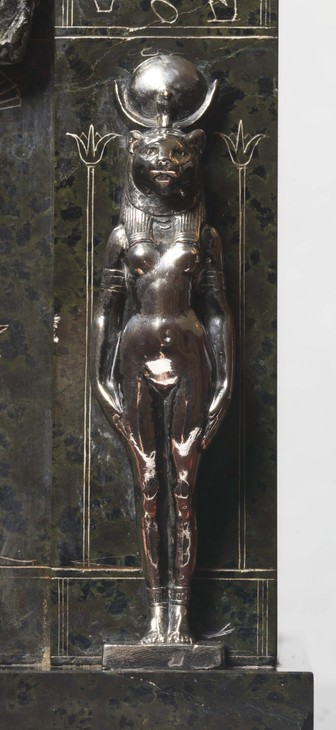

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of statuette of Bashtet on back of plinth)

Tate

Fig.4

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of statuette of Bashtet on back of plinth)

Tate

Various visual and iconographic details of The Singer and Applause resonate in light of these imperial contexts. The taut neck and head of The Singer, for example, makes her appear as if she is standing to attention, like a loyal imperial subject (fig.2). This effect is further emphasised by the four caryatid figures on the bases of both The Singer and Applause, who stand with straight backs, heads upright, legs and feet together, and arms pressed firmly by their sides (figs.3 and 4).7 The economic and cultural importance of Egyptian cotton for Britain’s textile industry might also come to mind when looking at the thin, flowing gown of the lute player on the extreme right of the upper register of the side panels of Applause (fig.5).

In interpreting the statuette, however, it is important to note just how lucrative Britain’s Indian and African empires were for Ford, and how closely related London, Cairo, and Calcutta were in the British imperial imagination in the late nineteenth century. After all, interpretations of The Singer and Applause should not only be made in relation to the question of Britain’s specific imperial interest in Egypt and Sudan during the 1880s but also must consider the global breadth of the British Empire in the late nineteenth century. As Jasanoff has made clear, there is an unusually close relationship between the history of British imperial interests in Egypt and the history of British empire building in and around India throughout the nineteenth century. For example, Jasanoff documents how Egypt was of increasing importance to Britain following Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, which challenged British dominance in the East by threatening to conquer rival territory more generally, and of bodies of land and water that were crucial stop-off points for Britons on their journeys to and from India.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 shortened the journey time from Britain to India by two thirds.8 From a British imperialist perspective, therefore, India and Egypt were ‘combined into a single geopolitical vision, uniting national security with commerce and creating a union of peoples on the ground’.9 In addition, Jasanoff states that, just as each Egyptian antiquity collected was a ‘trophy of victory’ over time, the sun and sand, so, too, was it part of a larger, and longer power play between Britain, France, and Egypt itself over who had the ‘right and responsibility to possess and protect antiquities’.10

Edward Onslow Ford

Maharajah Lakshmeshwar Singh 1899 Dalhousie Square, Kolkata (Calcutta)

Fig.6

Edward Onslow Ford

Maharajah Lakshmeshwar Singh 1899 Dalhousie Square, Kolkata (Calcutta)

Britain’s African empire was even more lucrative for Ford. As well as The Singer and Applause, Ford successfully marketed and sold statuette versions of the camel from his c.1887–9 General Gordon monument at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in 1889. Ford was also commissioned by the Royal Engineers Corp to provide a commemorative silver shield for Gordon’s sisters, and was asked by the imperial hero Frederick Roberts to produce a silver equestrian statue of his son, who had died in the battle of Colenso during the Boer War, a conflict commemorated by Ford’s Glory to the Dead 1901.13 While these are as little remembered now as Applause and The Singer, Ford’s imperial work was much admired by his contemporaries. A.C.R. Carter commented, in 1898, that India had been the source of some of Ford’s most ‘important work’.14 And Walter Armstrong, referring to the quantity of work that went to India, publicly lamented that so many of Ford’s best statues ‘should be sent so far away’.15

Perhaps unsurprisingly in the context of fin-de-siècle imperialism, the racial profiles of Ford’s neo-Egyptian figures also interested contemporary commentators. For example, an anonymous visitor to Ford’s studio, writing in The Pall Mall Gazette in April 1889, suggested that the face of The Singer was of a ‘strong Egyptian type’.16 Compared to the comparatively flat-nosed and thick-lipped, white-marble Egyptian figures produced in the third quarter of the nineteenth century by Anglo-American sculptors such as William Theed, William Wetmore Story and Edmonia Lewis, or the more explicitly ethnographic approach of mid-century French sculptor Charles Henri Joseph Cordier, it is difficult to understand why Ford’s contemporaries thought the face of The Singer to be especially ‘Egyptian’.17 It should be noted, however, that in comparison to Story’s, Lewis’s and Theed’s mid-century, marble Cleopatra figures, whose heads tended to be covered in nemes, Ford’s Egyptian girls could have been viewed in racial terms because of their emphatically rendered hair (fig.7). The hair on The Singer has clear braiding, as does the figure in Applause (fig.8). In addition, given Queen Victoria’s widely reported purchase at the Great Exhibition of Cordier’s black bronze Said Abdallah, de la Tribue de Mayac, Royaume de Darfour 1848 and polychrome bronze African Venus 1852, both Ford’s polychromy and the addition of dark wax to the surface of The Singer, potentially align Ford’s neo-Egyptian works with Cordier’s earlier ethnographic project.18

Notes

Pip Laurenson, ‘The Singer’, Material Matters: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture, London 1999, p.35.

The photograph was originally published in Robinson’s Members and Associates of the Royal Academy, 1891, Photographed in their Studios. Frank Rinder, ‘Edward Onslow Ford, R.A.’, Art Journal, February 1902, p.60. For more on sculptors’ responses to Gordon’s death, see Adam White, Hamo Thornycroft and the Martyr General, Leeds 1991.

G. Alex Bremner, ‘Between Civilization and Barbarity: Conflicting Perceptions of the Non-European world in William Theed’s Africa, 1864–69’, Sculpture Journal, vol.16. no.1, Spring 2007, p.100.

Maya Jasanoff, Edge of Empire: Conquest and Collecting in the East, 1750–1850, New York 2005, p.288.

For more on the imperial politics of Anglo-Egyptian relations in the second half of the nineteenth century, see Bremner 2007, pp.94–102.

In fact, ‘erect’ is the word contemporaries most frequently employed to describe The Singer. The Pall Mall Gazette of 12 April 1889 described how ‘the body stands erect’; The Standard of 17 June 1889 described the figure as ‘nude, supple, and erect’; while The Graphic of 22 June 1889 described the girl as ‘standing erect, with her fingers touching the strings of a harp’. It may also be important that the four caryatid figures standing to attention on the base of Applause are animal-headed divinities, rather than mere mortals. These are the kilted figure of Thoth on the front left, the hawk-headed Horus, on the front right, the cow-headed Hathor, on the back left, and the cat-headed Bastet on the back right. That they are animal-headed suggests the supposedly primitive character of Egyptian culture.

Before the opening of the Suez Canal, a voyage from Britain to India would take six months via the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa.

Beattie 1983, pp.219–20; M.H. Spielmann, ‘Edward Onslow Ford, R.A. 1875’, British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-Day, London 1901, p.52

Rinder 1902, p.60; Ford’s roundel portrait of William Holman Hunt, for one of the niches along the facade of the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colour, suggests the sculptor had an interest in the ‘Biblical’ and ‘Imperial’ Middle East.

Anon., ‘Around the Artists’ Studios: A Forecast, IV: At Mr. Onslow Ford’s Studio’, Pall Mall Gazette, 12 April 1889, p.3.

There is a sophisticated body of scholarship on the question of race in Roman-American and British marble sculptures with Egyptian subjects in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, such as William Wetmore Story’s Cleopatra 1862, Edmonia Lewis’s Death of Cleopatra 1876, and William Theed’s Africa group from the Albert Memorial 1864–9. The critical discussion includes Charmaine Nelson, The Colour of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in the Nineteenth Century, Minneapolis 2007, pp.143–79; and Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject, Durham 2010, pp.133–207. Ford’s views on such art are difficult to gauge. At the first meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Art and its Application to Industry in 1888, he praised the exemplary attitude of mid-century American sculptor Horatio Greenough, and suggested that a visitor to London ‘may be led to suppose, in looking at the Albert Memorial’, that the British had made up their ‘minds to have one big thing, and have done with the whole business’ of sculpture for ever. See Edward Onslow Ford, ‘Modern Renaissance in Sculpture’, Transactions of the National Association for the Advancement of Art and Its Application to Industry, London 1888, n.p.

For more on questions of race in the nineteenth-century Egyptian Revival, see Scott Trafton, Egypt Land, Durham 2004. For more on Cordier, see Christine Barthe, Laure de Margerie and Edouard Papet (eds.), Facing the Other: Charles Cordier (1827–1905): Ethnographic Sculptor, Paris 2005 and Barbara Lawson, ‘The Artist as Ethnographer: Charles Cordier and Race in Mid-Nineteenth-Century France’, Art Bulletin, vol.87, no.4, December 2005, pp.714–22.

How to cite

Jason Edwards, ‘Ford and Empire’, April 2013, in Jason Edwards (ed.), In Focus: 'The Singer' exhibited 1889 and 'Applause' 1893 by Edward Onslow Ford, Tate Research Publication, April 2013, https://www