Victorian Eclecticism

In modelling the main figures of The Singer and Applause, Ford obviously did not adopt what the mid-Victorian art theorist Owen Jones described in the Description of the Egyptian Court Erected in the Crystal Palace (1854) as the ‘peculiar character’ of ancient Egyptian sculpture.1 As evidence of how this was perceived, the comments of Victorian journalist Samuel Sharpe in the same publication are revealing: Sharpe condemned the ‘simple’ attitudes of Egyptian sculpted figures, the way in which figures looked ‘straight forward’, ‘whether standing or sitting’, the manner in which fingers and toes tended to be ‘straight and unformed’, the unrealistic shortness of the figures’ waists, and the fact that there was little apparent interest in portraiture, motion or facial expression.2 Nevertheless, Ford’s statuettes reveal his real and wide-ranging interest in Egyptian and Egyptian Revival material, in a variety of scales, in a diverse array of media, and from a disparate range of locations. These interests are reflected in the statuettes’ religious and musical themes, in the hieroglyphics Ford employed on the bases of The Singer and Applause, in the harp and architectural shape of the pedestal of The Singer and in the details of the statuettes’ hairstyles and headdresses.

Cleopatra's Needle, Victoria Embankment, London

Fig.1

Cleopatra's Needle, Victoria Embankment, London

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer (detail of plinth)

Tate

Fig.2

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer (detail of plinth)

Tate

19th-dynasty Pectoral of Ramses II c.1279–1213 BC

Louvre, Départment des Antiquités Égyptiennes (N767)

Fig.3

19th-dynasty Pectoral of Ramses II c.1279–1213 BC

Louvre, Départment des Antiquités Égyptiennes (N767)

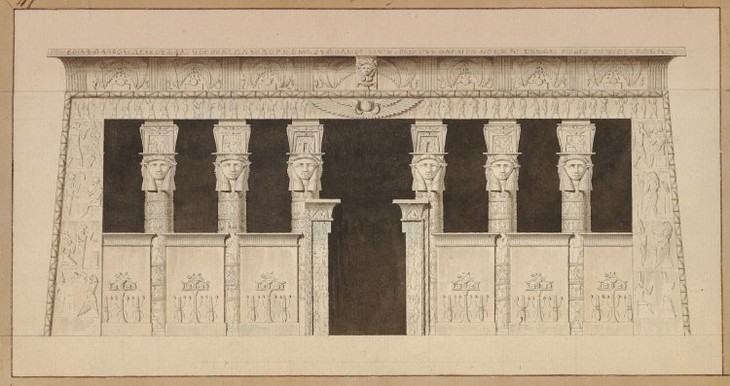

Dominique-Vivant Denon and Louis-Pierre Baltard

The Temple at Dendera 1802, from Voyage dans la Basse et la Hauté Egypte, vol.2, 1802, in plate 39, fig.3

Engraving on paper

214 x 377 mm

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.4

Dominique-Vivant Denon and Louis-Pierre Baltard

The Temple at Dendera 1802, from Voyage dans la Basse et la Hauté Egypte, vol.2, 1802, in plate 39, fig.3

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (side view)

Bronze, coloured resin paste and semi-precious stones

902 x 216 x 432 mm

Tate N01753

Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1894

Tate

Fig.5

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (side view)

Tate N01753

Tate

Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Pastime in Ancient Egypt Three Thousand Years Ago 1863

Oil on canvas

995 x 1357 mm

Harris Museum & Art Gallery

Fig.6

Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Pastime in Ancient Egypt Three Thousand Years Ago 1863

Harris Museum & Art Gallery

The harp in The Singer (fig.5) may have derived at least in part from Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Pastimes in Ancient Egypt, Three Thousand Years Ago 1863 (Harris Art Gallery and Museum, Preston, fig.6), and one might speculate that Ford sought, with The Singer and Applause, to create the successful sculptural equivalent of Alma-Tadema’s popular Egyptian canvases. Ford’s neo-Egyptian statuettes seem to follow more closely the example of Alma-Tadema’s preference for more bourgeois, antique scenes than the mid-century Anglo-Roman marbles celebrating the comparatively aristocratic figure of Cleopatra. It should also be noted that the two artists had a close relationship at this particular moment in their careers, emblematised by the painter’s portrait of Ford’s daughter, Clothilde Enid completed in 1888, and Ford’s 1895 sculpted portrait bust of Alma-Tadema (Royal Academy, London). In 1889, the pair also collaborated on furniture for the Marquand Mansion in Manhattan.5 With this in mind, it is possible to speculate that Ford intended his works to appeal to Alma-Tadema, since the painter included an Egyptian-themed room in his studio-home and acknowledged that his Egyptian pictures were his ‘personal favourites’.6

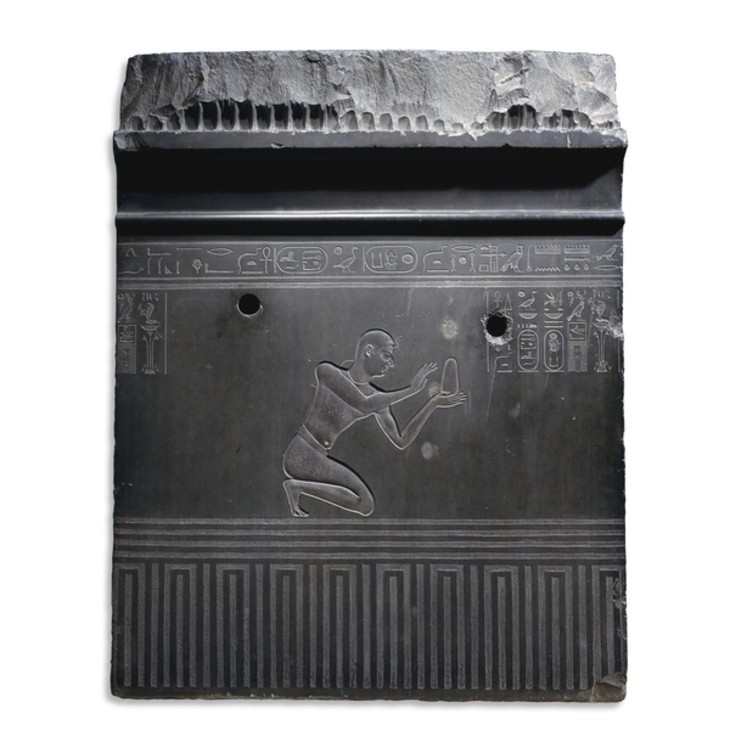

In working on Applause, Ford may also have consulted two architectural slabs in the British Museum, donated in 1766 by King George III: the thirtieth-dynasty slab of Nectanebo I (fig.7) and the twenty-sixth-dynasty slab of Psamtik I (fig.8). If so, Ford may have misunderstood their iconography as the crouching (male) figures are not applauding, but offering to a deity.

Basalt slab of Nectanebo, Egypt 30th Dynasty, c.370 BC

Height 1226 mm (max.) Depth: 390 mm

Gift of King George III (1766)

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.7

Basalt slab of Nectanebo, Egypt 30th Dynasty, c.370 BC

Gift of King George III (1766)

© Trustees of the British Museum

26th-dynasty limestone slab of Psamtik

EA 20

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.8

26th-dynasty limestone slab of Psamtik

EA 20

© Trustees of the British Museum

The crown in Applause (fig.9), with its red and turquoise bosses, and intricately braided snake, suggests that Ford may also have attended one of the first performances of Verdi’s Aida in the mid-1870s, or saw an illustration of it, as there is a clear relationship between this crown and a surviving piece of costume jewellery from the production dating from c.1876 (fig.10). There may also be a relationship between The Singer (fig.11) and the designs for the Paris debut of Aida at the Opéra de Paris on 22 March 1880, as can be seen when comparing the statuette with Pierre-Eugène Lacoste’s c.1879–80 drawings of the costumes made for the production (fig.12).

Costume diadem for Aida c.1876

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Fig.10

Costume diadem for Aida c.1876

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (side view)

Bronze, coloured resin paste and semi-precious stones

902 x 216 x 432 mm

Tate N01753

Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1894

Tate

Fig.11

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (side view)

Tate N01753

Tate

Pierre-Eugène Lacoste

'Harp Player' costume design (1879–1880) for the Paris Opening of Aida at the Opéra de Paris (Salle Garnier) March 22 1880

Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Fig.12

Pierre-Eugène Lacoste

'Harp Player' costume design (1879–1880) for the Paris Opening of Aida at the Opéra de Paris (Salle Garnier) March 22 1880

Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Thus, although it is clear that Ford drew upon and synthesised an array of ancient and modern sources while working on The Singer and Applause, the meaning of Ford’s eclecticism still needs to be established. This will be done by considering the relationship between the main sculpted figures designed by Ford and the hieroglyphic variants that he depicts in relief form upon the side panels of the two statuettes.

It is important to note, however, that in the bottom-left corner of the right side panel, and the top-right corner of the left side panel of The Singer, there is a miniature, hieroglyphic version of the main figure in Applause (fig.13). Similarly, the top-left figure of the upper register of the orchestra that Ford depicts on the right side panel of Applause, and the top-right figure of the upper register of the orchestra on the left side panel, are miniature, hieroglyphic versions of The Singer (fig.14). What might Ford have intended by this juxtaposition of figures?

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

Tate

Fig.13

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

Tate

The synthetic use of multiple stylistic sources in late nineteenth-century British art, known today as ‘Victorian eclecticism’, is generally understood as either a product of aesthetic over-confidence (a demonstration of British artists’ certainty that they were able to master all styles from all periods) or as an example of Victorian under-confidence (evidence that British artists, unlike their French peers, were unable to come up with an original modern style, and so returned endlessly to historical precedents). The same criticism has been levelled at the nineteenth-century Egyptian revival, which is more often than not characterised as ‘Egyptomania’, a term that suggests that artists were less concerned with the careful selection and synthesis of sources for a particular purpose, but rather yielded to a tasteless desire for, and lack of comprehension of, ancient Egyptian culture.

The Rosetta Stone Egypt, Ptolemaic Period, 196 BC, from Fort St Julien, el-Rashid (Rosetta)

1123 x 757 x 284 mm

Excavated by Pierre François Xavier Bouchard. Gift of George III.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.15

The Rosetta Stone Egypt, Ptolemaic Period, 196 BC, from Fort St Julien, el-Rashid (Rosetta)

Excavated by Pierre François Xavier Bouchard. Gift of George III.

© Trustees of the British Museum

The Rosetta Stone, which entered the British Museum’s collection in 1802, was one of the spoils of the successful British conflict with France in Egypt three years earlier (fig.15). It juxtaposes the same text in two Egyptian scripts (hieroglyphs and demotic) and Greek, which famously enabled Jean-François Champollion to decipher hieroglyphs. By juxtaposing his harpist and applauding figure in two different sculptural ‘languages’ – one hieroglyphic, the other contemporary European – for the purposes of visual translation and comparative evaluation within an imperial frame, Ford may have been trying to develop a visual stylistic equivalent of the linguistic variety on the Rosetta Stone, a kind of ‘Rosetta aesthetics’.

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi

David c.1440s

Museo Nazionale del Bargello

Fig.16

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi

David c.1440s

Museo Nazionale del Bargello

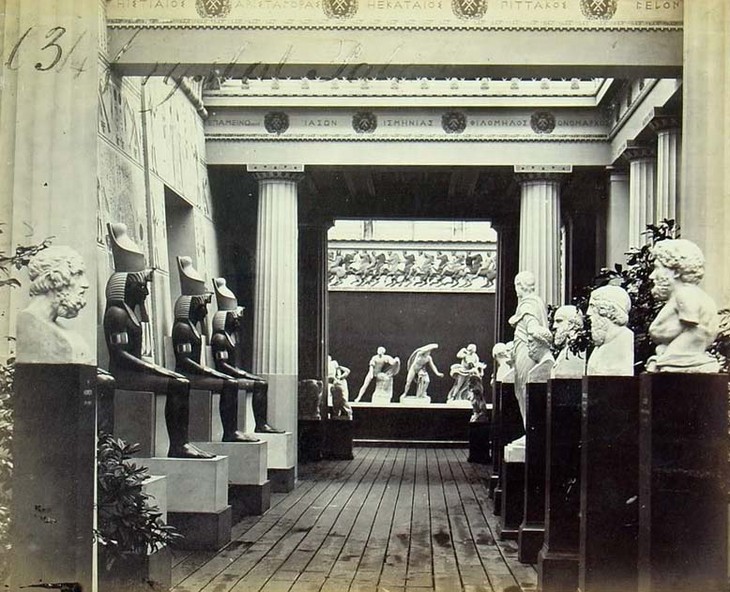

To what extent, though, might the fully three-dimensional, comparatively realistic figures of the two statuettes articulate the imperial triumph of European realistic modelling over Egyptian, relief-carved hieroglyphic stylisation? As cultural historian Stephanie Moser has pointed out, the ‘perceived contrast between Greek movement and Egyptian stasis’, in nineteenth-century histories of ancient sculpture, was a key way of articulating the Victorians’ attitude towards the comparative ‘cultural dynamism’ of Egypt and Greece. Contemporary commentators certainly interpreted the ‘lack of movement’ in Egyptian sculpture as representing both the ‘inferior artistic skill’ of the Egyptians and their culture’s aesthetic stagnation.14 According to Moser, from the publication of J.J. Winckelmann’s History of Ancient Art (1764) onwards, Egyptian art was repeatedly seen as a foil to classicism, and Winckelmann’s ‘progressivist scheme’ for the history of art proved the ‘primary intellectual framework’ according to which the Egyptian antiquities were presented at the British Museum and elsewhere.15

Period photograph of the passageway connecting the Greek, Roman and Egyptian courts at the Crystal Palace Sydenham c.1854–1936

Fig.17

Period photograph of the passageway connecting the Greek, Roman and Egyptian courts at the Crystal Palace Sydenham c.1854–1936

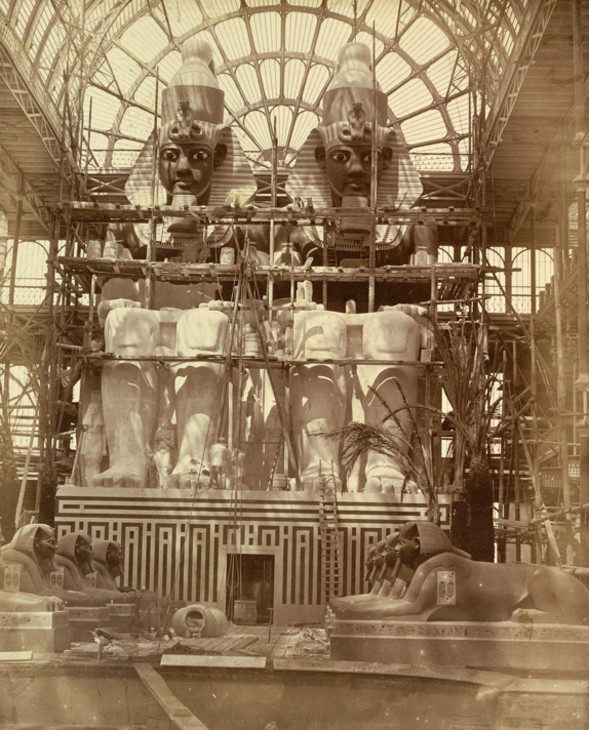

Philip Henry Delamotte

The Colossi Of Aboo Simbel in Process of Painting 1855

Photographic print

Photo © The British Library Board

Fig.18

Philip Henry Delamotte

The Colossi Of Aboo Simbel in Process of Painting 1855

Photo © The British Library Board

With this in mind, by drawing a visual parallel between the main clapping figure of Applause and the miniature, hieroglyphic variant on the side panel of the base of The Singer, Ford could be said to encourage reflection on the comparative merits of the two modes of figuration. If so, then Ford’s agenda chimes with the similarly comparative, historicising and imperial aims of Owen Jones’s and Joseph Bonomi’s 1854 guide to the Egyptian Courts of the Crystal Palace, Sydenham. Jones and Bonomi assumed that readers would be familiar with, and proud of the Rosetta Stone, forcibly acquired from Napoleon’s Egyptian troops in 1802. Like the Rosetta Stone, Jones’s and Bonomi’s popular guides invited comparison between several languages, emphasising the authors’ imperial mastery of them all: for example, Jones noted that the Temple of Abu Simbel, discovered by Jean-Louis Burckhardt in 1816 and reproduced at a reduced scale within the Crystal Palace was called ‘Aboo Simbel’ by Arabs, ‘Abshak’ by the ancient Egyptians, and ‘Aboccis’ by Roman geographers (fig.18).16

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

Fig.19

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of plinth)

Tate

Fig.20

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of plinth)

Tate

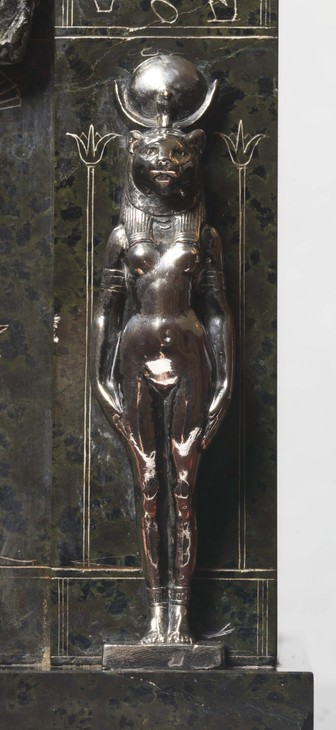

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of statuette of Bashtet on back of plinth)

Tate

Fig.21

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of statuette of Bashtet on back of plinth)

Tate

In this context, it is important to consider the potentially strategic, as well as decorative, function of the four statuettes at each corner of the bases of The Singer and Applause; strategic because these figures seem to exemplify Sharpe’s critical comments on the ‘simple’ attitudes of Egyptian sculpted figures, ‘whether standing or sitting’. Like those that Sharpe criticised, the four caryatid statuettes on the bases of The Singer and Applause ‘look straight forward’ and stand with their hands hanging ‘down on each side’ (fig.21), whereas the bodies of the main figures cannot be said to lack ‘motion’, nor their faces ‘expression’.20

Finally, the two registers of figures, including an outlined harp player that Ford depicts on the side panels of Applause, should also be considered. While the lower register of figures represents what Jones described as the Egyptian ‘attitude of walking’ in the ‘prescribed position’ with ‘the left being in advance of the right leg’, Ford depicts the harpist – similar to The Singer – on the extreme left of the upper register, putting its weight on its forward right leg, while its left leg trails behind (fig.22).21

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of plinth)

Photo: Tate

Fig.22

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of plinth)

Photo: Tate

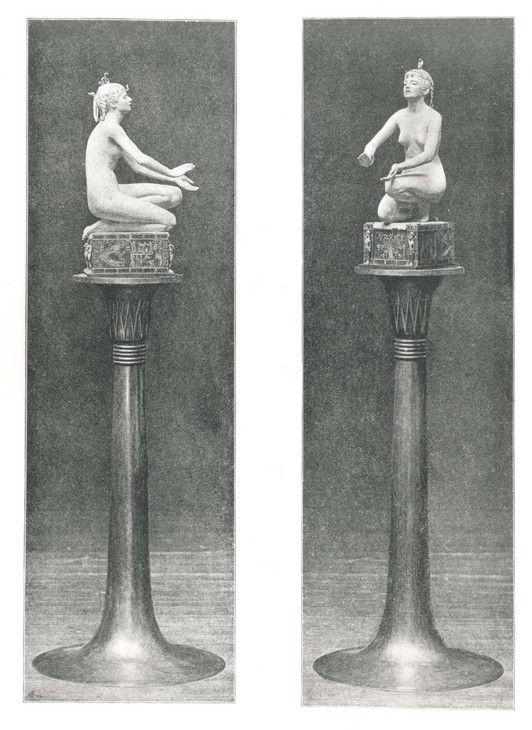

Period photographs showing original pedestal forApplause 1893

Fig.23

Period photographs showing original pedestal forApplause 1893

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of front plinth)

Tate

Fig.24

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of front plinth)

Tate

Examples of Egyptian ornaments, from Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament (1856)

Fig.25

Examples of Egyptian ornaments, from Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament (1856)

By the late 1880s, however, as Ford’s neo-Egyptian statuettes demonstrate, the taste for primary colours and predominant palettes of red, blue, and yellow had changed. For the enamel-work on the pedestal of The Singer, Ford employed ‘flat tints’ and used ‘neither shadow nor shade’, as Jones claimed that the ancient Egyptians had done. Ford was also happy to outline his pedestal serpents and birds against a dark green-to-black background, as Jones had again recommended, using both colour and form ‘conventionally’ in Jones’s terms.28 However, following the fashionable, ‘greenery-yallery’ tones of the aesthetic movement, Ford employed secondary tones of red, blue and green on the base of The Singer, and did without yellow, preferring gold for outlines and highlights (fig.26).29 Ford’s decorative preference for gold highlights in The Singer and Applause, however, were not entirely without Egyptological precedent: Samuel Sharpe claimed in the guide to the Egyptian Courts at Sydenham that the Egyptians had made considerable use of the ‘gold mines of the Nubian desert’.30

In this comparative and hierarchical context of ancient sources and modern styles, it is useful to consider the links between The Singer and the book Travels to the Source of the Nile, written by the Scottish explorer James Bruce in 1813, as the popularity of the harp motif within Egyptian Revival work dated largely from Bruce’s discovery, in 1768, of the so-called ‘Tomb of the Harpers’, in western Thebes, which contained a bas-relief representation of two blind harpists playing before the gods. It seems likely that Ford was familiar with at least some of this tomb’s iconography given that images of it were widely reproduced. There is a particular resemblance between the harp of The Singer and the instrument illustrated in Bruce’s Travels (fig.27). In both cases, the harps are floor-standing, human-scaled, boat-based, and have more than ten strings. Their bases also feature decorative figures wearing Egyptian crowns: in Bruce’s case, pharaonic figures wearing crowns sacred to the gods Ra and Horus, in Ford’s a red-crown-wearing, ibis-headed Thoth figure. Furthermore, Ford’s and Bruce’s representations both classicise their hieroglyphic source material according to contemporary European standards.

With Bruce’s Travels in mind, The Singer might also be understood as a late-Victorian exemplar of an imaginary paragon between harp designers, ancient and modern. Bruce believed that it was impossible to ‘construct’ or ‘finish’ a harp of ‘any form with more taste and elegance’ than the ancient examples he had unearthed in Thebes, meaning that in the paragon between the arts of ancient Egypt and Greece, harp-making was a rare case in which Egyptian work was ‘more elegant’. Like Bruce’s ancient Egyptian examples, the bottom and sides of Ford’s harp ‘seem to be [ve]neered, and inlaid, probably with ivory, tortoise-shell and mother-of-pearl’, but, in Ford’s case, these are not the ‘ordinary produce of the neighbouring deserts and seas’, as they would have been in ancient Egypt, but, and perhaps more impressively, the product of a trans-continental imperial export business. The juxtaposition in The Singer of a realistic neoclassical figure and a neo-Egyptian harp therefore keeps the question open as to which of the two aesthetic sensibilities was preferred.31

Just as Egyptian art was considered a foil to the classical tradition in European art history, so, too, did Egyptian sculpture function as a foil to the contemporary British sculpture displayed at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, including the plaster cast of Ford’s General Gordon after it was bequeathed to the directors following the sculptor’s death in 1901. One of the main purposes of the Egyptian Court was to emphasise the comparative skill of modern European and imperially educated colonial sculptors who, like Ford, proved themselves able to master a diverse array of geographical and historical styles. This fact was registered by Jones’s guidebook, which documented that the various statues at Sydenham had been first ‘restored’ by Egyptologist Joseph Bonomi, and then carved in plaster by the Anglo-Italian sculptor Raffaelle Monti and a ‘very intelligent body of French workmen’.32

In spite of how plausible the claims may be for the imperial resonance of Ford’s eclecticism, there is a risk of overstating the idea that the use of ancient source material in Victorian art can only be understood according to historicist, hierarchical or imperial terms. Jones’s and Bonomi’s guidebook, for example, encouraged visitors to the Crystal Palace to contrast the Egyptian ‘Avenue of Lions’ with the contemporary Italian sculptor Antonio Canova’s neoclassical depictions of the same creature, confident that the ‘superiority of the Egyptian idealised form over the attempted imitation of a natural lion carved in stone’ would be ‘very apparent’ to viewers.33 The Singer and Applause may be seeking to make a similar point, suggesting the equivalent status, within Victorian eclecticism, of ancient Egyptian and contemporary European sculpture, or even the richness of ancient Egyptian material culture as a resource for contemporary sculptors. However, the visual hierarchy of the different styles in The Singer and Applause, with the more classical figure produced at a considerably larger scale than the hieroglyphic versions, and the sense in which Ford embeds the hieroglyphics below, as if in an earlier, archaeological strata, may provide the bigger clues to the artist’s aesthetic sensibility.

Notes

Owen Jones and Joseph Bonomi, Description of the Egyptian Court Erected in the Crystal Palace, London 1854, p.3.

See J.-M. Humbert, M. Pantazzi and C. Ziegler, Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art 1730–1930, exhibition catalogue, Musée du Louvre, Paris 1994, pp.352–3.

See Danielle O. Kisluk-Grosheide, ‘The Marquand Mansion’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol.29, 1994, pp.151–81.

Vern G. Swanson, The Biography and Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, London 1990, p.165.

James Stevens Curl, The Egyptian Revival: An Introductory Study of a Recurring Theme in the History of Taste, London 1982, p.152.

Anon., ‘The Royal Academy’, The Times, 29 June 1889, p.17. An anonymous contributor to the Manchester Guardian of 6 May 1893 similarly described the ‘lithe Egyptian girl’ depicted in Applause as ‘crouching or squatting’ in an ‘attitude proper to Egyptian art’. See Anon., ‘Royal Academy’, Manchester Guardian, 6 May 1893, p.9.

Marion Hepworth Dixon, ‘Onslow Ford, R.A.: An Imaginative Sculptor’, Architectural Review, vol.8, 1900, p.258.

M.H. Spielmann, ‘Edward Onslow Ford, R.A. 1875’, British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-Day, London 1901, pp.54–5.

For more on the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, see John Kenworthy-Browne, ‘Plaster Casts for the Crystal Palace, Sydenham’, Sculpture Journal,vol.15, no.2, 2006, pp.173–99; Ian Leith, Delamotte’s Crystal Palace: A Victorian Pleasure Dome Revealed, London 2005; and Jan Piggott, Palace of the People: The Crystal Palace at Sydenham 1854–1936, London 2004. In terms of comparative aesthetics, David J. Getsy suggests a third possibility: that the ‘self-reflexivity of the interplay between representation and materiality’ in Ford’s work is part of his proto- or para-Modernist ‘metasculptural challenge’. See David J. Getsy, ‘Hard Realism: The Thanatic Corporeality of Edward Onslow Ford’s “Shelley Memorial”’, Visual Culture in Britain, vol.3, no.1, April 2002, pp.53–76, reproduced p.73.

For example, in 1898, Dixon suggested that Ford sought to make viewers ‘love the ... deformities’ of his ‘immature young model[s]’. Dixon 1898, pp.294, 296.

Dixon described Folly as having ‘claw-like feet’, and ‘prominent’ knee caps and ankle-bones’ (Dixon 1898, pp.294, 296), while two years later she argued that, in Ford’s adolescent girls, ankles were inclined to be thick, knees pointed, and arms ‘wantonly and gratuitously thin’ (Dixon 1900, pp.257–60).

It must, however, be noted that Jones’s assertion of unwavering symmetry in Egyptian design is problematic. As Neal Spencer revealed to me, Ford’s asymmetrical relief scene is far from exceptional in ancient Egyptian contexts.

In Act II of Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic operetta Patience, satirising the Aesthetic Movement (first performed in 1881), male aesthetes are famously characterised as ‘greenery-yallery, Grosvenor Gallery / Foot-in-the-grave young m[e]n’.

James Bruce, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772, and 1773, 2nd edn, Edinburgh 1805, pp.37–8, 284, 286. In addition to Plate 4, the base of the harp belonging to The Singer might be compared with the sculpture of a boat with Queen Mutemwia acquired by the British Museum in 1834, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=111455&partid=1 , accessed 27 September 2011.

Jones and Bonomi 1854, pp.26, 28. Although Jones writes about French workmen, surviving photographs suggest that jobbing Anglo-Indian carvers were also employed. See Philip Delamotte, ‘Setting up the Colossi of Rameses the Great’, in J.R. Pigott, Palace of the People: The Crystal Palace at Sydenham 1854–1936, London 2004, p.47.

How to cite

Jason Edwards, ‘Victorian Eclecticism’, April 2013, in Jason Edwards (ed.), In Focus: 'The Singer' exhibited 1889 and 'Applause' 1893 by Edward Onslow Ford, Tate Research Publication, April 2013, https://www