Canvas and its Preparation in Early Twentieth-Century British Paintings

Sarah Morgan, Joyce H. Townsend, Stephen Hackney and Roy Perry

Walter Sickert, Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner showed a particular commitment to exploring new techniques in their choice of canvases and preparatory layers. In this essay, first published in 2008, Sarah Morgan, Joyce Townsend, Stephen Hackney and Roy Perry explore the diversity of materials used and consider its significance in the context of early twentieth-century British painting.

Edwardian conservatism and the development of a distinctly modernist style in painting contextualise British art of the early twentieth century. This was the last great period of portraiture when artists such as Augustus John (1878–1961) and Sir William Orpen (1878–1931) made their reputations and fortunes through the art market’s taste for aristocratic elegance. At the same time, young artists such as Harold Gilman (1876–1919), Spencer Frederick Gore (1878–1914) and Charles Ginner (1878–1952), under the influence of Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942), proclaimed their commitment to the importance of French art of the later nineteenth century and to the concept of ‘purity’ in art.

Technical examination and analysis of a group of Tate paintings (Table 1) by Sickert, Gilman and Gore for a Tate catalogue on Camden Town artists revealed the diversity of materials used (Table 2), and the careful consideration given by these artists to the qualities of the canvas and preparatory layers used. It also lent greater understanding to the relationship between the three artists. Comparison with contemporary painters, such as Orpen, Ginner and others, provides a deeper understanding of the characteristics and function of the canvas and preparatory layers found on early twentieth-century British paintings.

Among the variety of products supplied by artists’ colourmen c.1900 was a broad range of prepared canvases. The main types of cloths used for painting supports continued to be made from linen (flax), cotton and some coarser weave fibres such as jute or hemp, which could be used on their own or mixed to produce different types of material. In turn, the fibres could be woven to produce cloths with particular weave types and of different weights. Colourmen offered unprimed canvas for sale on the roll, or in lengths or pre-stretched, but also primed with a variety of single, full or double preparations.1

Table 1 Details of paintings whose supports were studied.

| Artist | Artist’s dates | Accession number | Title | Date | Dimensions (mm) |

| Gilman, Harold | 1876–1919 | T00096 | Edwardian Interior | c.1900–5 | 533 x 540 |

| Gilman | N05783 | French Interior | c.1905–7 | 622 x 514 | |

| Gilman | N05831 | Lady on a Sofa | exh. 1910 | 304 x 406 | |

| Gilman | N03684 | Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord | c.1913 | 464 x 615 | |

| Gilman | N05555 | The Artist’s Mother | exh. 1913 | 610 x 508 | |

| Ginner, Charles | 1878–1952 | N05050 | The Café Royal | 1911 | 635 x 483 |

| Ginner | T03841 | Victoria Embankment Gardens | 1912 | 664 x 461 | |

| Gore, Spencer Frederick | 1878–1914 | T00027 | North London Girl | 1908–92 | 762 x 610 |

| Gore | N05859 | Inez and Taki | 1910 | 406 x 508 | |

| Gore | T06521 | Rule Britannia | 1910 | 762 x 635 | |

| Gore | N05099 | Mornington Crescent | 1911 | 635 x 762 | |

| Gore | N04675 | Letchworth | 1912 | 509 x 612 | |

| Gore | T01859 | The Beanfield, Letchworth | 1912 | 305 x 406 | |

| Gore | T01960 | The Cinder Path | 1912 | 686 x 787 | |

| Gore | T02260 | Café Singer | 1912 | ||

| Gore | N05100 | Richmond Park | 1914 | 508 x 762 | |

| Gore | T00496 | The Gas Cooker | 1913 | 730 x 368 | |

| Gore | T03561 | The Artist’s Wife | 1913 | 765 x 636 | |

| John, Augustus | 1878–1961 | N03171 | Woman Smiling | 1908–9 | 1960 x 982 |

| Manson, James Bolivar | 1879–1945 | N04929 | Self-Portrait | c.1912 | 508 x 397 |

| Orpen, William | 1878–1931 | T07136 | Anita | 1905 | 760 x 557 |

| Orpen | not Tate | Young Ireland – Grace Gifford | 1907 | not known | |

| Orpen | N02977 | The Angler | c.1912 | 914 x 864 | |

| Pissarro, Lucien | 1863–1944 | N03179 | High View Fish Pond | 1915 | 533 x 648 |

| Rutherston, Albert | 1881–1953 | N04996 | Laundry Girls | 1906 | 914 x 1168 |

| Rutherston | N04569 | Paddling | 1910 | 2273 x 2013 | |

| Sands, Ethel | 1873–1962 | N03845 | The Chintz Couch | c.1910 | 464 x 384 |

| Sickert, Walter Richard | 1860–1942 | N05045 | Les Arcades de la Poissonerie, Dieppe | c.1900 | 610 x 502 |

| Sickert | N05093 | Venice, La Salute | c.1901–3 | 451 x 692 | |

| Sickert | N03621 | A Marengo | c.1903 | 381 x 457 | |

| Sickert | T03548 | La Hollandaise | c.1906 | 511 x 406 | |

| Sickert | N05090 | L’Américaine | 1908 | 508 x 406 | |

| Sickert | N05088 | Rowlandson House – Sunset | 1910–12 | 610 x 502 | |

| Sickert | N05430 | Off to the Pub | c.1912 | 508 x 406 | |

| Sickert | N03846 | Ennui | c.1914 | 1524 x 1124 | |

| Sickert | N05092 | Tipperary | 1914 | 508 x 406 |

Specific artists’ use of grounds

Sickert’s background is well known. The son of an artist, he studied briefly at the Slade School of Art (1879–82) and then under Whistler (1882–3), a dominant influence on young British artists in the first decade of the century. He moved naturally between Britain and France between 1883 and 1898, during which time he met and worked with Edgar Degas and also associated with some of the most important artists of the French avant-garde: Monet, Pissarro, Gauguin, Signac, Bonnard and Vuillard. Sickert moved to Dieppe in 1898 and Les Arcades de la Poissonnerie, Dieppe was painted there c.1900 (Tate N05045). The canvas is fine linen, pre-primed and attached with steel tacks to a five-member strainer with three nails in each corner. The number 12 has been stamped onto the back, relating to the size of the canvas, a standard commercial French F12 format, most likely purchased from a Dieppe colourman.3 The back of the cloth appears dark and stained, possibly through wetting, and the canvas has become embrittled over time. It was originally prepared with a white priming, probably oil-based, over which a green/grey layer was applied by the artist. This modifying layer, either grey/green or sometimes grey/brown in tone, was found on all Sickert’s paintings studied dating from c.1889 to 1906, and reflects the influences of traditional French painting technique4 and of Whistler.5 In 1918, Sickert reflected on the importance of the role of the ‘colour of a given preparation’:

This preparation, that serves as a diving-board, may be, as with Franz Hals and David and Constable, a mere coat of havana, or it may be, as with Renoir, the ex-painter-on-china, a coat of white. It may be a coat of grey as with Whistler, or it may be an underpainting in one of the innumerable cameos, from the cold-grey of Rubens and Hogarth, to the vermilion and Prussian-blue of the ‘dead-colours’ of the beginning of the nineteenth century. But it is on the interaction of such grounds with the painting proper that the complete master of the medium relies. To use the housepainter’s expression, the ground ‘grins through’. And the artist, in giving his final coat of colour, never quite lets go the hand of his preparation.6

Gilman trained at the Slade from 1897 until 1901, where he met Gore, and his earliest Tate work was started towards the end of this period. He painted portraits throughout his career and Edwardian Interior c.1900–5 (Tate T00096) is a good early example of his pictures of women in a domestic interior. Gilman selected fine, plain-weave linen, which is stretched across a four-member stretcher. The canvas retains its selvedge along the right-hand side and is unevenly cut along the three outer edges. The now-yellowed white priming penetrates through the close weave to the back of the canvas in places. The priming retains the weave texture, and since it covers all of the canvas it must have been applied before stretching. It is composed of a single layer of lead white with kaolin and chalk and traces of extenders. This basic type of canvas and preparation is consistent in all Gilman’s Tate paintings. No canvas stamps were found, which could argue that the canvases were not purchased pre-primed, but it is difficult to be certain whether Gilman bought the raw materials and prepared the canvases himself. It is fair to say, however, that they reflect a consciously economical choice of materials, both technically and financially. There is no visible evidence of any further preparatory layers in this painting but it is difficult to discern the lower layers, as it was executed over an extended period of time in multiple layers. Gilman applied his paint in a fairly fluid state, striving to keep the application of new paint as fresh and clean as possible. The apparent absence of any sizing layer over the canvas (in contrast to the known commercial primings examined) and the single white priming containing a high proportion of kaolin, chalk and extenders in this painting would have provided a slightly absorbent surface on which to work. This may have been intended to facilitate drying and the illusion of a direct painting technique, seen in the work of Whistler, Sickert (see below) and French alla prima technique. However, as a young painter, Gilman was perhaps not as adept at handling this technique as the artists who influenced him, and there is evidence (highly yellow/white fluorescent, thin layers of oleoresinous material, presumed to be varnish, occurring between less fluorescent layers of paint) that he applied local varnish, certainly in later paint layers, to seal and wet out earlier work before continuing to paint.

Table 2 Canvas fibre type, identified by optical microscopy, and priming type, obtained from optical microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX) of cross-sections taken from the tacking margins, which often included the canvas. Aqueous acid fuchsin staining for proteins was used to localise glue size layers. (x = no canvas stamp on the canvas.)

| Artist | Accession number | Canvas and fibre analysis (size described when present) | Canvas stamp | Surface colour of priming | Analysis of priming(s) |

| Gilman | T00096 | linen, plain, close weave, rough, uneven threads, flax warp and weft, quite degraded | x | white or off-white | single layer of lead white with kaolin and chalk, presumed oil medium |

| Gilman | N05783 | linen, plain, tight weave, flax warp and weft with thick glue size | x | white or off-white | single layer of lead white and extenders in presumed oil medium |

| Gilman | N05831 | linen, plain, close weave, rough, uneven threads, flax warp and weft, quite degraded, no info on size | x | white or off-white | single thin layer of lead white priming with a trace of chalk, presumed |

| Gilman | N03684 | linen, flax fibres, closely woven, plain weave illegible stamp with handwritten number, probably canvas batch number | x | white or off-white | single layer of lead white priming with a trace of kaolin, presumably oil medium |

| Gilman | N05555 | linen, plain, tight weave, degraded flax warp and weft | x | white or off-white | single layer of lead white with traces of extenders, presumed oil medium |

| Ginner | N05050 | linen | Winsor & Newton 388 | white | |

| Ginner | T03841 | jute warp and weft, plain coarse weave, thin glue size | x | cool grey oil type | thin, opaque lithopone and gypsum probably in oil, over thicker, transparent gypsum and synthetic ultramarine priming, possibly in glue |

| Gore | T00027 | flax warp and weft, plain weave, with thick glue size on surface | Percy Young/Gower Street/London | white or off-white oil type | single layer of pure lead white, presumed oil medium |

| Gore | N05859 | hemp warp and weft, plain weave, black cotton fibre for selvedge, glue size on canvas | P. Shea of ‘56 Fitzroy Street, Tot. Court Rd, London W’ | white | single layer of lead white over wet lead white /chalk |

| Gore | T06521 | plain, slightly open weave, yellowed hemp warp and weft with less yellowed flax selvedge and thin glue size | x | white or off-white oil type | thin, opaque lead white, chalk and zinc drier(?) over thicker, transparent mix of chalk, gypsum, lead white and zinc white, presumed oil medium for both |

| Gore | N05099 | linen – fibres not analysed | Percy Young | white or off-white oil type | thin lead white and chalk over thick chalk, zinc white and barytes, presumed oil medium for both |

| Gore | N04675 | flax warp and hemp weft, plain weave, glue size on canvas | Percy Smith | white or off-white oil type | double priming of lead white and small amounts of kaolin and chalk, presumably in oil, over chalk and zinc sulphide (probably) in an unknown medium, with oiling-out between |

| Gore | T01859 | plain weave, thick hemp weft and thin, paler, flax warp, glue size on canvas | x | white | thin, opaque lead white, kaolin and chalk, glue size, then thicker, more transparent, gypsum with extenders and synthetic ultramarine, probably oil medium for both – resembles priming of Ginner T03841 of same date |

| Gore | T01960 | plain weave, hemp warp and weft, very degraded, thick glue size may have been applied hot | x | white | thin, opaque layer of lithopone and chalk over thicker, more transparent chalk/gypsum and zinc white, presumed oil medium for both |

| Gore | T02260 | linen, simple, twill weave, flax warp and weft, glue size on canvas | x | white or off-white oil type | single layer of pure lead white with a trace of chalk/gypsum, presumed oil medium |

| Gore | N05100 | flax warp and weft, plain weave, with thick glue size on surface George Rowney & Co ‘B’ canvas size on surface | x | white | single layer of lead white with varied extenders, presumed oil medium |

| Gore | T00496 | linen, plain, close weave, flax warp and weft, glue size on canvas | P. Shea/Artists Colourman/56 Fitzroy Street/Tot Crt Rd/ London W1 | white or off-white oil type | thin, opaque lithopone and chalk, probably in oil, over thick, transparent chalk/gypsum, barytes and zinc white, in oil or other medium |

| Gore | T03561 | plain, slightly open weave, yellowed hemp weft and less yellowed flax warp with thin glue size | Percy Young | white or off-white oil type | thin, opaque, lithopone and chalk/gypsum over zinc white and chalk/ gypsum(?), presumed oil medium for both |

| John7 | N03171 | canvas | white | lead white and chalk in presumed oil medium | |

| Manson | N04929 | linen, plain and close weave, flax fibres | P. Shea | white or off-white | lithopone, chalk and extenders over lower layer of chalk, presumed oil medium with zinc driers for both |

| Orpen (Taor 2006) | T07136 | Student Canvas, J. Barnard and Son, London W. | white | lead white in presumed oil medium over chalk, zinc white and cobalt blue | |

| Orpen (Taor 2006) | not Tate | linen, plain weave | none | white | lead white over chalk, zinc white and lead white, presumed oil medium |

| Orpen (Taor 2006) | N02977 | jute for warp and weft, very coarse plain weave | ‘Chenil by the Town Hall Chelsea’ within palette outline, ‘4S’ outside | lithopone in presumed oil medium over chalk, zinc white, lead white and cobalt blue | |

| Rutherston | N04569 | flax – not clear if this was warp and/or weft glue size over canvas | not able to examine | white | single layer with proteinaceous medium |

| Rutherston | N04996 | linen, flax fibres, plain weave, two threads in each direction, thin glue size | Roberson and Percy Young/ Gower Street/London WC | white or off-white | two layers of lead white priming with extenders, presumed oil medium |

| Sands | N03845 | paper board with glue size | x | none | glue size and a small amount of kaolin and gypsum |

| Sickert | N05045 | Number ‘12’ canvas | Number ‘12’ | white | |

| Sickert | N05093 | linen, plain weave with flax warp and weft, glue size on canvas | L Cornelissen & Son/22 Great Queen Street/London | white | single layer of priming of lead white, kaolin and chalk extenders, presumed oil medium |

| Sickert | N03621 | cotton canvas | x | white | double white priming of lead white/chalk/presumed oil over chalk/lead white/protein |

| Sickert | T03548 | hemp warp and weft, plain weave, thin glue size | white | lead white and chalk over gypsum and zinc white, with unexplained Cl in lower layer | |

| Sickert | N05090 | plain weave, thick hemp warp, thinner flax weft, glue size on canvas | Percy Young/Gower Street | white | thin layer of lead white, chalk, zinc white and kaolin over thicker chalk, zinc white and lead white, presumed oil medium for both |

| Sickert | N05088 | loosely woven, plain weave canvas with degraded flax threads and a thin glue size | Shea/Artists Colourman/56 Fitzroy Street/Tot | white | fragmentary priming of chalk and a trace of zinc white, probably one layer, glue or egg or glue/egg mixture |

| Sickert | N05430 | P Shea/Artists Colourman/56 Fitzroy Street/Tot Crt Rd/ London W | white | upper layer of lead white, chalk and kaolin, lower layer chalk and kaolin, both may have Zn drier | |

| Sickert | N03846 | canvas | L Cornelissen & Son | white | glue medium8 |

| Sickert | N05092 | plain weave linen with flax threads | J Bryce-Smith/117 Hampstead Road/London | white | lead white, kaolin and chalk extenders |

During his time in Dieppe (1898–1905), Sickert made several lengthy visits to Venice to paint. A Marengo c.1903 (Tate N03621) was painted on one of these trips, on a medium weight but tightly woven cotton canvas. In his letters9 the artist detailed his ideal method of painting, referring to his use of ‘Canvases size 8’, probably the standard French size 8 canvas to which A Marengo indeed conforms. Pure cotton canvases were only found on paintings from the artist’s period in Italy and none of these has canvas stamps. In addition, the stretcher has a distinctive construction with dovetailed cross-section mortice and tenon joints (fig.1), which suggests that it was made in Italy. The cotton canvas was primed with two layers of lead white mixed with chalk, providing a slightly absorbent surface. Sickert’s aim in his sequence of Venice figure pictures was to work rapidly and give a sense of immediacy. In a later letter he described how he had adjusted his technique to facilitate this aim:

I have gained a great deal of experience working from 9 to 4 ... Not to paint in varnish. Not to embarrass the canvas with any preparations. And so to give the paint every chance of drying from the back of the canvas.10

Lower left corner of the original stretcher for Walter Sickert's 'A Marengo' c.1903

Tate N03621

Fig.1

Lower left corner of the original stretcher for Walter Sickert's 'A Marengo' c.1903

Tate N03621

Percy Young advertisement 1895–6

Tate Conservation Archive

Fig.2

Percy Young advertisement 1895–6

Tate Conservation Archive

Sickert returned to London from Dieppe in 1906 and during the same year painted La Hollandaise (Tate T03548) on a pre-primed canvas from the London colourman Percy Young, whose faded stamp marks the back of the canvas and is also impressed into one of the stretcher bars, which implies it was bought ready stretched. The cloth is coarsely textured hemp and has a circular inked customs stamp on the reverse, suggesting that the cloth was imported. Young, based at 131 Gower Street, close to Sickert’s Fitzroy Street studio, was a publisher, importer and manufacturer of artists’ materials who specialised in the supply of foreign canvases and oil colours at Paris prices (fig.2).11 Sickert does not appear to have purchased consistently from the same London colourmen during this period. However, he does seem to have favoured those, like Young, who specialised in foreign artists’ materials, French in particular, and to have moved away from the more established English manufacturers, such as Roberson and Cornelissen, whom he had used with some regularity earlier in his career. This may reflect a conscious desire to use French materials, confirming his commitment to avant-garde French art, which was at the heart of the modern movement in English painting. Having returned from France so recently, he may also have been looking for practical ways to obtain materials with the qualities that he currently favoured. The canvas was sized with hot glue that soaked into the threads, and fully primed with a lower layer of gypsum, zinc white and kaolin extenders followed by a thin opaque upper layer of lead white, chalk and extenders. The priming retains much of the rough canvas weave texture and must have provided a slightly absorbent preparatory surface. The opaque mid-grey preparatory layer common to his works of this period was loosely brushed onto the white primer. The coarse canvas and grey preparatory layer enabled Sickert to work economically, applying the paint in blocks of opaque colour that sank into the surface on drying, but leaving areas of the grey ground exposed, so that the surface does not appear heavily worked. In the final stages of painting, the artist worked vigorously, scumbling paint over the rough canvas weave texture, preserving the illusion of a spontaneous painting executed from life.

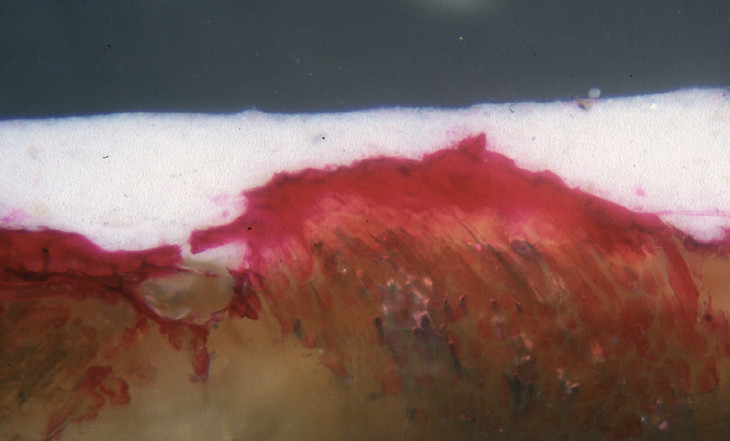

Cross-section from the primed tacking margin from Spencer Gore's 'Richmond Park', stained for proteinaceous material with aqueous acid fuchsin (original magnification 125x). The positive stain indicates a very thick size layer over the canvas and little penetration to the canvas fibres because the size was probably cold and viscous when applied.

Tate T05100

Fig.3

Cross-section from the primed tacking margin from Spencer Gore's 'Richmond Park', stained for proteinaceous material with aqueous acid fuchsin (original magnification 125x). The positive stain indicates a very thick size layer over the canvas and little penetration to the canvas fibres because the size was probably cold and viscous when applied.

Tate T05100

Orpen12 was one of the leading portrait painters of the Edwardian period, his work encapsulating his sitters in a mode of aristocratic elegance that earned him his reputation while still a Slade student. Like Augustus John, he became a renowned personality within the art world, ‘famed for his glittering success, his Rolls-Royces and absence of any intellectual curiosity’.13 His conservative taste and drive for personal success positioned him in opposition to Sickert and the young modern painters who saw art as a social activity. Orpen’s portrait of Young Ireland – Grace Gifford, dated 1907, discussed by Taor,14 exemplifies his work of this period. The artist held accounts with Roberson and Chenil & Co., from whom he purchased materials from at least 1907. The canvas for Young Ireland is plain-weave linen of non-standard size, suggesting it was made to order or was modified after or during painting, a regular practice with Orpen. The double white priming consists of a thicker lower layer of chalk, zinc white and lead white with an upper layer of lead white, historically referred to as a ‘flatting layer’.15 This traditional preparation, favoured by the artist, provided a finely textured, well-sealed, bright white surface and is associated with high quality British manufacture. Orpen commonly applied a dark or mid-toned imprimatura to be utilised in a mid-ground technique. A thin, dark toning layer of lead white, bone black and cobalt blue was found on Young Ireland, and functions as a mid-tone in the sitter’s flesh and dress. For Orpen, as for Sickert, who continued to work on coloured grounds up until at least 1910, this enabled him to work more quickly and to avoid the surface appearing heavy or overworked, conveying an impression of rapid and skilful execution.

Sickert had originally met Gore in Dieppe in 1904 and later (1914) paid generous tribute to the younger painter’s influence on his work.16 Certainly by 1906, when Sickert had returned to England, the artists were learning from each other and often painting in the same studio. It was probably Gore who reintroduced the artist to Lucien Pissarro, who later became a member of the Fitzroy Street Group. The group’s influence on Sickert post-1907 is most visible in the change in his palette, which can be tentatively seen in L’Américaine of 1908 (Tate N05090), the artist’s portrait of a market girl. The painting makes an interesting comparison with Gore’s North London Girl in the same genre, painted in 1908–9 (Tate T00027). Their supports were both supplied by Percy Young. Sickert chose a coarsely woven, linen and hemp mix canvas, sized and pre-primed with a lower layer of chalk, zinc white and lead white and a thinner upper layer of lead white, chalk, zinc white and kaolin probably in an oil medium, which may be of French origin, given its supplier and atypical (in this study) zinc white content. Gore selected a plain coarse-weave linen canvas in a traditional ‘head size’ format, pre-primed with a single layer of pure lead white, not commonly found on commercially primed canvases of British origin. Sickert applied a thin imprimatura of grey/brown colour, which retained the rough canvas texture and would have been slightly absorbent, facilitating the drying of the overlying layers. The lower paint layers were reasonably viscous, so the paint bounced across the surface and was partly rejected by the dry underlayer, reinforcing the texture of the canvas. Little of the preparatory layers are visible, and some small patches of white paint applied as highlights are evidence that Sickert utilised some kind of mid/dark ground technique. In contrast, Gore’s pure lead white priming provided a bright white impermeable paint and varying his brushwork to retain the character of each form; working wet-in-wet, rapidly sketching and applying short directional strokes of pure colour leaving the white priming exposed. There are superficial similarities in the brushwork at the surface of Sickert’s painting, which signal a tentative change in technique, but what is important here is that the basis of his technique encapsulated in the preparatory stages appears to remain the same.

The New English Art Club (NEAC), which was founded in 1886 to provide an alternative to the Royal Academy, rejected Gilman’s work until 1909. Lady on a Sofa (Tate N05831) was accepted by the NEAC for exhibition in the summer of 1910. The subject recalls Gilman’s earlier works and is of the same broad genre as L’Américaine and North London Girl. There is a clear transition in technique in this painting moving from his early fluency to the rigorous patterning of his later works. Gilman described his new way of working earlier in the same year:

the juxtaposition of small pieces of paint of the moderns is a new technique. In this way one can work from light to dark (setting light as high as its colours will allow), or from dark to light, all over a painting at one go or labouring at part only of the canvas. One can work upon dry paint without oiling out, correct without niggling, labour without pain.17

The artist loaded full-bodied paint onto a small brush and worked in dabs and short strokes across the surface of the primed canvas. Bright accents of white priming are left exposed between juxtaposed brushstrokes, as Gilman built up a lively surface texture. His choice of canvas and preparatory materials is similar to that found in earlier works, except that the linen canvas is slightly rougher in texture with uneven threads, either characteristic of the cloth or caused by rubbing the cloth prior to use. Again the priming, lead white with traces of chalk, probably bound in oil, has penetrated through the canvas in places. The resulting preparatory surface was slightly absorbent, white and with a rough tooth, capable of taking opaque, oil paint of a heavy paste-like consistency.

It is interesting to speculate whether Gilman influenced Sickert in his choice of canvas and grounds at this time. Rowlandson House – Sunset of 1910–12 (Tate N05088) marks a significant shift in Sickert’s choice of preparatory layers. It is the earliest work by Sickert at Tate in which he used an absorbent white ground, and painted directly onto the primed canvas. The pre-primed canvas was purchased from P. Shea, a colourman local to his Fitzroy Street studio and who, like Young, probably supplied foreign artists’ materials. The linen canvas has a very fine open weave, typical of French or Belgian manufacture, and was primed with a thin layer of chalk and zinc white bound in a proteinaceous medium (identified by staining for protein with aqueous acid fuchsin), providing an absorbent ground for oil painting. It reflects early Whistler influences but also that of modern French painting, and the use of pure colour. Absorbent grounds were thought to preserve colour due to leaching of the oil medium, which in time would discolour the paint.18 We can see this effect in Rowlandson House, where the impasted areas and upper paint layers appear richer in medium, except in some of the darker areas where the artist may have extracted medium prior to painting. In addition we see in some areas a dense build-up of different coloured layers, recalling Gilman and Gore’s techniques; the mass of the building to the left is an olive green over purple and a thin red layer, for example.

Gilman was initially the strongest advocate for a new group to supersede the Fitzroy Street Group, but it was Gore, Sickert’s most trusted friend in the group, who was elected as president of the Camden Town Group, formed in 1911 and known for its depiction of urban landscapes and ordinary working class life in the Camden Town district of London. Gore moved to 31 Mornington Crescent in the same year, a few doors away from Sickert who lived at number 6. There were gardens directly in front of the house, and Gore made many paintings of the subject including Mornington Crescent 1911 (Tate N05099). Gore’s practice was either to paint directly from nature, or else to paint in the studio, working from drawings made on the spot. The view, taken from ground level from within the park itself, may perhaps have been painted outdoors. Gore chose a linen, plain open-weave canvas, attached to a stretcher with evenly spaced tacks, with a Percy Young stamp impressed into one of the stretcher bars. The painting conforms to a standard commercial ‘three-quarter size’ format but the canvas edges have been crudely cut, perhaps suggesting that Gore had the canvas restretched after painting onto a Percy Young stretcher. There may be a minimal size layer present beneath the double priming consisting of a lower layer of chalk, zinc white and barites over an upper layer of lead white and chalk, which extends to the tacking edges and retains the strong canvas weave texture. Gore seems to have favoured a white double ground and he may have experimented by purchasing alternatives to pure lead-based primers in the upper layer, initially, as in this work, reducing the proportion of lead white and adding other materials, including zinc white and later replacing lead white altogether. Alternatively, the colourman may have done the experimentation, from motives of health and safety. Zinc white has been found in artists’ tube paint from the 1890s to the 1930s, but is not yet common by this date, to judge from analysis carried out by the authors on British paintings. The addition of pigments such as chalk and barytes was also thought to reduce the risk of cracking and imparted a tooth to the canvas.19 The combination of the open canvas weave texture and the bright white surface with a good tooth is skilfully utilised by Gore in this painting, both to vary his handling and in its relationship to his palette.

Charles Ginner, who joined the Fitzroy Street circle in 1910 and later became one of the founder members of the Camden Town Group, trained in Paris and was one of the few English artists to have confronted post-impressionism before Roger Fry’s exhibition in 1910, Manet and the Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Galleries, London. He and Gilman quickly struck up a close friendship, cemented by a trip to Paris in late 1910 with Frank Rutter, an art critic who had joined the group by 1908, to see collections of modern art. The two artists are perhaps best known for their highly impasted paint surfaces, which led them to be infamously described by Sickert as ‘the thickest painters in London’.20 Their use of ‘thick paint’ presented certain technical challenges to the artists and we have seen how Gilman’s choice of support and preparatory layers may have been designed to deal with this. Ginner’s painting of The Café Royal 1911 (Tate N05050) is painted on an identifiable canvas supplied by Winsor & Newton, whose stamp and product number 388 mark the back of the canvas. The cloth is an ‘Artists Flax [linen] Prepared Canvas specially woven; a very coarse heavy canvas for large pictures boldly treated’.21 The non-standard dimensions indicate that the support was not purchased ready stretched, but that the artist bought the canvas on the roll, and possibly primed, cut and stretched it himself. The roll was 85 inches wide (216 cm) and was a more economical means of purchasing materials. It also allowed Ginner to experiment with the format of his canvases and his preparatory layers.

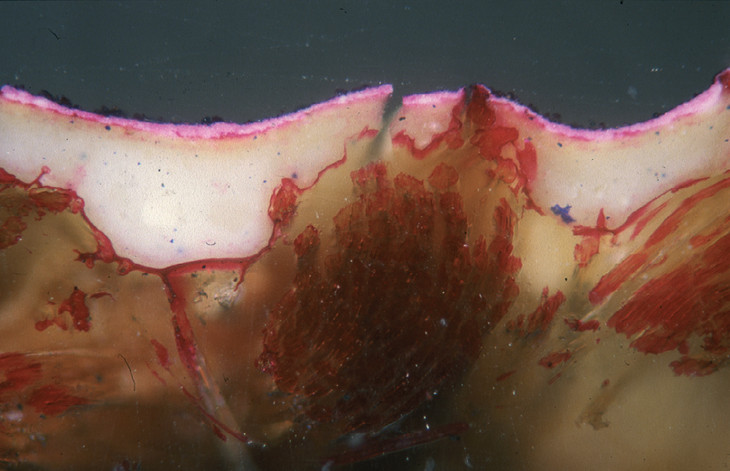

Cross-section from the primed tacking margin from Charles Ginner's 'Victoria Embankment Gardens', stained for proteinaceous material with aqueous acid fuchsin (original magnification 100x). The positively stained intense crimson areas indicate a very thin size layer overlying the canvas, and provide evidence that the size was able to penetrate to the surface of individual fibres in the canvas threads. Thus it was free flowing and therefore hot when applied.

Tate T03841

Fig.4

Cross-section from the primed tacking margin from Charles Ginner's 'Victoria Embankment Gardens', stained for proteinaceous material with aqueous acid fuchsin (original magnification 100x). The positively stained intense crimson areas indicate a very thin size layer overlying the canvas, and provide evidence that the size was able to penetrate to the surface of individual fibres in the canvas threads. Thus it was free flowing and therefore hot when applied.

Tate T03841

Conclusion

Sickert, Gore, Gilman and Ginner were at the forefront of a group of artists committed to modern painting in Britain during the period 1900–13. Examination of their choice of canvases and preparatory layers reflects developments in their painting techniques and in the practical working relationships between the artists. The sophisticated level of experimentation is perhaps unsurprising in the work of Sickert but more surprising in that of Gore, a much less experienced painter, and of Ginner, who is known for the consistency of his painting style. The influence of French painting is clearly evident in their choice of materials. There are examples of the direct use of foreign materials, French in particular, which could be obtained easily from artists’ colourmen in London by the end of the nineteenth century,22 as well as by group members when they travelled in Europe. Sickert’s materials also directly reflect changes in his geographical location: he travelled more than the others. Gilman’s work is remarkable for its consistency, which sets him apart from the rest of the group. While his choice of materials was, at least partly, related to technical considerations it is likely that it was also motivated by financial constraints – as a student and as an artist struggling to establish himself particularly following the breakdown of his marriage in 1909. The exchange of ideas and materials and methods between the three core painters, during the period studied, and between Gore and Ginner is a consistent feature. And while Sickert’s reputation and seniority historically overshadow the younger painters, he was clearly much influenced by them in his choice of canvas and preparatory layers. The other artists whose primings are listed in Table 2 for comparison also used a variety of types, that were certainly not restricted to the double layer of lead white and chalk that was prevalent among British artists in Tate’s collection until the end of the nineteenth century.

Notes

Leslie Carlyle, The Artist’s Assistant: Oil Painting Instruction Manuals and Handbooks in Britain 1800–1900, with Reference to Selected Eighteenth-Century Sources, Archetype, London 2001, pp.177–8, 447–9, app.22.

Gore T00027 has been previously dated to 1911, but this study revealed a stretcher label on the reverse, stating ‘1908/09’.

French canvases could be bought pre-primed and stretched in a range of standard sizes, which were fixed for all French suppliers. Each size was available in three formats: figure, paysage and marines, and a range of different weights: ordinaire, fine and coutil. David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery, London 1990, pp.45–6.

Stephen Hackney, ‘Colour and Tone in Whistler’s “Nocturnes” and “Harmonies” 1871–72’, Burlington Magazine, vol.136, no.1099, October 1994, pp.695–9.

Walter Sickert, ‘Thérèse Lessore’, Art and Letters, November 1918, in Anna Greuztner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.429.

N. Wade, The Materials and Techniques of Walter Richard Sickert, unpublished dissertation, Courtauld Institute of Art, London 2004.

For further information on this colourman, who ceased trading in 1920, see http://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/artists-their-materials-and-suppliers.php , accessed May 2011, the website of the National Portrait Gallery, London, which includes a directory of British artists’ suppliers and colourmen, 1650–1939.

All technical information on this work is from Sally Taor, A Technical Study of Eight Works by William Orpen, unpublished dissertation, Courtauld Institute of Art, London 2006. Taor examined Tate works by Orpen for this project, with Joyce Townsend. Her dissertation provides an excellent example of the varied documentary sources which can offer information on support and preparatory layers.

‘To come down to historical fact, I may as well say that it is my practice that was transformed from 1905 by the example of the development of Gore’s talent’, Walter Sickert, ‘Whitechapel’, New Age, 28 May 1914, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.371–2.

Walter Sickert, ‘The Thickest Painters in London’, New Age, 18 June 1914, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.378–81.

Winsor & Newton trade catalogue, contemporary date, Ian Macginnis, Painting and Technical Advisor, Winsor & Newton, personal communication.

Joyce H. Townsend, ‘The Materials Used by British Oil Painters Throughout the Nineteenth Century’, Reviews in Conservation, vol.3, 2002, pp.46–55. See the National Portrait Gallery website, http://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/artists-their-materials-and-suppliers.php .

Acknowledgements

This essay was first published in Joyce H. Townsend, Tiarna Doherty, Gunnar Heydenreich and Jacqueline Ridge (eds.), Preparation for Painting: The Artist’s Choice and its Consequences, Archetype Publications Limited, London 2008. Reproduced here by permission of the publisher.

Mornington Crescent was examined and treated by Maureen Cross, former Tate conservator. Art historical text for the Camden Town catalogue has been produced by Robert Upstone and Nicola Moorby, both Tate curators, who gave access to their notes. Information and insight into Gore and the other painters’ working practice and characters was generously provided by Frederick Gore with support from Connie Gore. Supplementary information on artists’ colourmen was supplied by Cathy Proudlove of the Norwich Castle Museum.

Sarah Morgan is a former Conservation Administrator, Tate.

Joyce H. Townsend is Senior Conservation Scientist, Tate.

Stephen Hackney is the former Head of Conservation Science, Tate.

Roy Perry is the former Head of Conservation, Tate.

How to cite

Sarah Morgan, Joyce H. Townsend, Stephen Hackney and Roy Perry, ‘Canvas and its Preparation in Early Twentieth-Century British Paintings’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www