Turner Bequest XXXV 1–89

Sketchbook bound in boards, covered in brown calf leather with seven brass clasps

92 leaves (and 1 modern replacement leaf) of white wove paper; various leaves watermarked ‘1794 | J Whatman 1794’ and ‘E & P | 1796’; page size 370 x 274 mm

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘Yorkshire | Tweed | Lakes of Cumberland – Westmorland | Lancashire | York’ on back cover

Numbered 141 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest on folio 1 recto (D01094)

92 leaves (and 1 modern replacement leaf) of white wove paper; various leaves watermarked ‘1794 | J Whatman 1794’ and ‘E & P | 1796’; page size 370 x 274 mm

Inscribed by Turner in ink ‘Yorkshire | Tweed | Lakes of Cumberland – Westmorland | Lancashire | York’ on back cover

Numbered 141 as part of the Turner Schedule in 1854 and endorsed by the Executors of the Turner Bequest on folio 1 recto (D01094)

Exhibition history

References

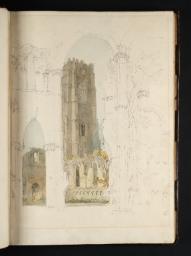

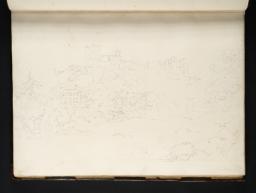

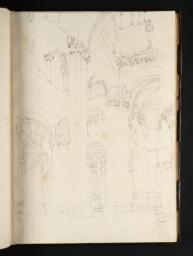

With the North of England sketchbook (Tate; Turner Bequest XXXIV) this book is the principal record of Turner’s important and wide-ranging tour as far as the Scottish Borders in the autumn of 1797; see that sketchbook’s Introduction for full details of the journey. It is the larger of the two books, and the largest Turner had used to this date. Like the North of England book it is filled with elaborate drawings, and it contains more watercolours. Overall it conveys a slightly different character, with its expansive Lakeland subject matter, the first properly ‘Sublime’ scenery that he had tackled on anything like an appropriately grand scale. The format of the book permitted this for the first time – some drawings made on the Midland tour of 1794 and in the South Wales sketchbook of 1795 (Tate; Turner Bequest XXVI) treat hilly or rocky coastal subjects, but they are on a much smaller scale. So substantial indeed are some of the studies here that they acquired the status of independent works of art; as Finberg noted,1 one leaf showing Patterdale Old Hall entered the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.2

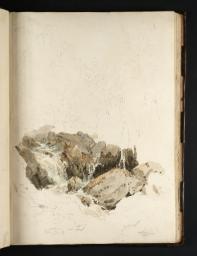

Despite these observations, it should be recorded that in Turner scholar David Hill’s view, Turner’s response to the Lakes does not suggest ‘a mountaineer’s sensibility’.3 Hill implies that Turner’s aesthetic is still essentially that of the Picturesque rather than the Sublime, concentrating on calm water and tree-clad shores rather than rugged passes. An exercise in the ‘pure’ Picturesque of rustic decay is the view of Ambleside Mill, folio 66 recto (D01053; Turner Bequest XXXV 51), which he used as the basis for a watercolour exhibited at the Royal Academy. There are, nevertheless, some studies of the rocky and inhospitable heights, as for example on folio 49 recto (D01037: Turner Bequest XXXV 35), recording a lead mine on a bleak upland road. There are several drawings partially coloured to suggest grand weather conditions or sumptuous light effects. A striking instance of the Lakeland experience leading Turner directly to the Sublime is the coloured drawing of a storm on folio 40 recto (D01086; Turner Bequest XXXV 84), which prompted one of the most dramatic of his early oil paintings.

That sheet raises an issue that emerges into prominence in this book: the question of when and where Turner added watercolour to his pencil outlines. Both in this book and in its companion, the North of England book, some subjects have been partially worked up in colour. As Jerrold Ziff notes,4 a drawing in the Hereford Court sketchbook of the following year (Tate D01324; Turner Bequest XXXVIII 70) was evidently coloured on the spot, as rain-marks in the pigment indicate, but a more elaborate version of the same subject on the next page, supports his view that the more finished colour studies were executed after the journey in question. However, some appear almost certainly to be on-the-spot records of conditions observed at the time: the studies at Fountains Abbey, folio 11 recto (D01082; Turner Bequest XXXV 80), and Tynemouth Priory in the North of England book (Tate D00939; Turner Bequest XXXIV 33) for instance. The rainstorm recorded on folio 40 recto (D01086; Turner Bequest XXXV 84) may, as Ziff thinks,5 have been completed in colour once Turner had returned to his lodgings; but it seems clear that he had a box or wallet of watercolours with him on his daily outings and used it from time to time in appropriate conditions. John Ruskin says that he tended to colour his drawings at the inn after a day’s travelling during the early Swiss tour, and he may have followed that pattern on later foreign tours.6

Despite the important use that he made of such subjects as the view of Crummock Water and Buttermere on folio 40 recto (D01086; Turner Bequest XXXV 84), it is noteworthy that on the whole Turner took relatively little advantage of his Lake District studies. Some subjects were developed from the present sketchbook – Ambleside Mill, folio 66 recto (D01053; Turner Bequest XXXV 51) and Rosthwaite Bridge, folio 35 recto (D01090; Turner Bequest XXXV 88), are examples; and later, when confronted by large projects such as Whitaker’s History of Richmondshire7 and the Picturesque Views in England and Wales,8 he turned back to this book for a few subjects; but on the whole what he found in Westmorland and Cumberland was obliterated by his experience in the following year of the mountain scenery of Wales.

Finberg records Turner’s parchment label on the spine, partially destroyed, which read ‘[...] Tweed and Lakes [...]’.9

Jerrold Ziff, ‘Turner’s First Poetic Quotations: an Examination of Intentions’, Turner Studies, vol.2, no.1, Summer 1982, p.3.

See E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (eds.), Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin: Volume XIII: Turner: The Harbours of England; Catalogues and Notes, London 1904, pp.190, 452.

Technical notes

How to cite

Andrew Wilton, ‘Tweed and Lakes Sketchbook 1797’, sketchbook, August 2010, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, November 2014, https://www