Ancient Egyptian Sources

The Singer and Applause combine familiar elements of pharaonic iconography through a prism of contemporary aesthetics, and while certain elements are direct copies of ancient artefacts, in some cases perhaps from publications, others may be inspired by other sources, including Egyptian Revival objects dating from the early nineteenth century. Though the component parts of each sculpture are brought together in a manner that would have been unfamiliar to an ancient artist, the effect, seen through the eyes of a nineteenth-century viewer, would nonetheless have been both ‘Egyptian’ and ‘contemporary’. This would have been further enhanced by the stands for each sculpture, now lost, but clearly inspired by ancient Egyptian iconography.

Painted limestone relief showing a relative of the tomb-owner Djehutyhotep, wearing knotted diadem, 12th dynasty, c.1850 BC

British Museum EA 1150

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.1

Painted limestone relief showing a relative of the tomb-owner Djehutyhotep, wearing knotted diadem, 12th dynasty, c.1850 BC

British Museum EA 1150

© Trustees of the British Museum

Copper alloy figure of a queen or divine consort, inlaid with gold detail, Third Intermediate Period (1069-664 BC)

British Museum EA 54388

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.2

Copper alloy figure of a queen or divine consort, inlaid with gold detail, Third Intermediate Period (1069-664 BC)

British Museum EA 54388

© Trustees of the British Museum

Copper alloy statue of a woman, perhaps a God's Wife of Amun, Third Intermediate Period (c.800-700 BC)

British Museum EA 43373

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.3

Copper alloy statue of a woman, perhaps a God's Wife of Amun, Third Intermediate Period (c.800-700 BC)

British Museum EA 43373

© Trustees of the British Museum

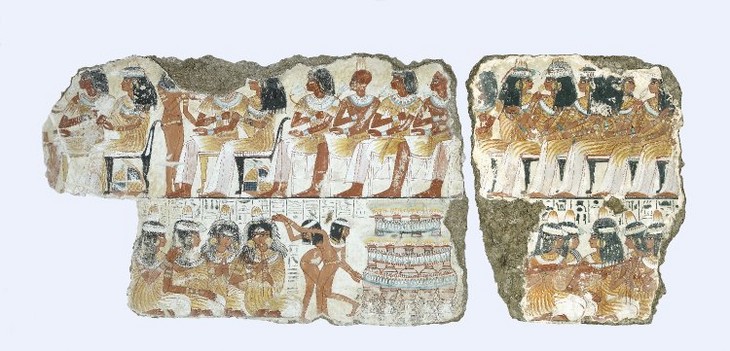

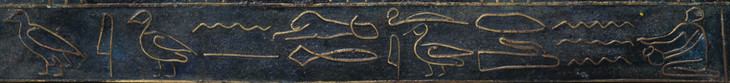

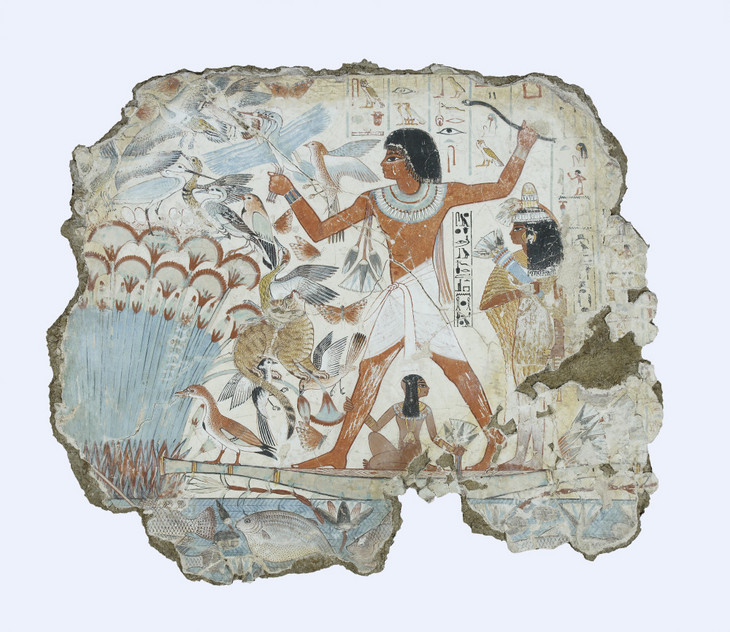

In tomb scenes of the eighteenth dynasty (c.1550–1069 BC), depictions of dancers became popular, with rows of guests being served wine, sat among tables of offerings, and it is from here that Ford must have drawn inspiration for the main elements of his two works (fig.4).3 Entertainment was often at hand in these banquets, with dancers, musicians and singers depicted. The dancers are often shown naked (as are the serving girls) but for a girdle and elaborately styled hair, captured in acrobatic poses. In contrast, the musicians are always clothed, playing the harp, lute, lyre, oboe and flute, accompanied by a lady keeping time, clapping. She is typically seated, alongside her fellow musicians. Ford has opted to capture the beauty of the young female body, in many ways similar to that of the dancers in the tomb scenes, but applies it to his musicians.

The pose of The Singer is, however, distinctly unpharaonic, with her subtly flexed leg, and arms held as she sings; few pharaonic statues or figures of harpists exist, and the ones that do are notably less languid (fig.5).4 The main figure of Applause, whether applauding a performance or forming part of it, is closer in pose to women depicted in pharaonic tomb and temple scenes.5 However, these women are clearly keeping time by clapping rhythmically; the title of Applause, therefore, suggests Ford misunderstood, or wished to re-interpret the ancient meaning.

The pose of The Singer is, however, distinctly unpharaonic, with her subtly flexed leg, and arms held as she sings; few pharaonic statues or figures of harpists exist, and the ones that do are notably less languid (fig.5).4 The main figure of Applause, whether applauding a performance or forming part of it, is closer in pose to women depicted in pharaonic tomb and temple scenes.5 However, these women are clearly keeping time by clapping rhythmically; the title of Applause, therefore, suggests Ford misunderstood, or wished to re-interpret the ancient meaning.

Banquet scene with musicians from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, 18th dynasty, c.1390 BC

British Museum EA 37981

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.4

Banquet scene with musicians from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, 18th dynasty, c.1390 BC

British Museum EA 37981

© Trustees of the British Museum

Painted wooden figure of a female harpist, Late Period (664-332 BC)

British Museum EA 48658

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.5

Painted wooden figure of a female harpist, Late Period (664-332 BC)

British Museum EA 48658

© Trustees of the British Museum

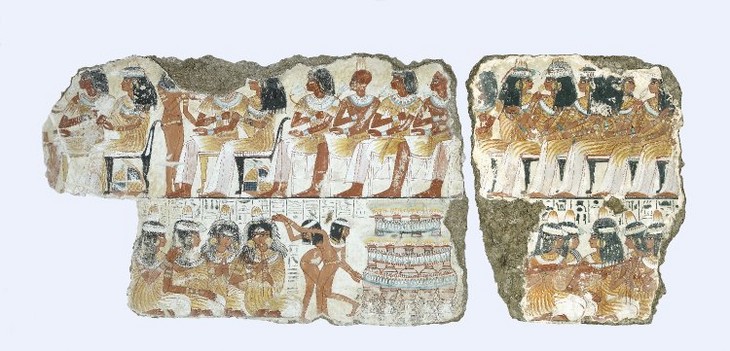

The hieroglyphic captions to these tomb scenes sometimes provide lyrics, for example in the eighteenth-dynasty tomb chapel of Nebamun at Thebes:

the scent which Ptah gives off,

and Geb has caused

his beauty to grow in every body

Ptah has done these things

with his hands in order to be restful of heart

The channels are filled with water anew

and the land is flooded with his love 6

and Geb has caused

his beauty to grow in every body

Ptah has done these things

with his hands in order to be restful of heart

The channels are filled with water anew

and the land is flooded with his love 6

No musical notation has survived for these songs to be resuscitated. The tomb scenes were popular stops at Luxor for tourists to visit from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, as they remain today, but the paintings from the tomb-chapel at Nebamun, on display in the British Museum since 1835,7 allowed a much wider audience to access such art, alongside a myriad of lavishly illustrated publications, from the Description de l’Egypte (1822) onwards.8

Ford’s Applause and The Singer thus echo Egyptian representations of entertainers – figures who were far from the top strata of society and only present to entertain the wealthy tomb owners, be they priests, military men, government officials or royal family members. Yet Ford has framed the two figures in iconography from royal statuary, and on their bases, in motifs from formal cult temples, tomb scenes and associated objects.

Ford was not inspired by Egyptian bronzes in terms of scale. Thousands of ancient examples survive, but relatively few of them are over 50 cm in height, above which wooden and stone sculpture was generally preferred. The majority of these bronzes depict deities, whether anthropomorphic, theriomorphic or hybrid in appearance, and were generally intended as ex-voto offerings to be placed in temples, though some images had different functions.9 As with The Singer and Applause, however, these pieces were cast using the direct lost-wax process, although there is limited evidence, in the ancient Egyptian context, for indirect lost-wax casting, which allows multiple copies to be made from the same prototype. Both hollow- and solid-cast bronze figures and statues are known, and many were decorated with inscriptions, or embellished with inlays and gilding.

In The Singer (fig.6), the main figure wears a bob wig, held in place by a diadem embellished with an ibis head. While the bob wig seems to echo hairstyles seen on representations of women from the Old Kingdom onwards (see fig.5), the ibis represents the god Thoth, and is rather inappropriate in this context. Rather, a rearing cobra (uraeus) or a vulture head representing the goddess Mut or Nekhbet would be expected here.

Nonetheless, the form of wig and diadem are perhaps indirectly based on tomb scenes showing such headgear, which also inspired jewellery, costumes and opera sets of the early nineteenth century. The discovery of diadems and gold jewellery found in the royal pyramids at Dahshur by Jacques de Morgan in 189410 provided ancient examples where the front of the diadem typically supports a rearing cobra.11

The Singer holds a tall eleven-string arched harp, a form familiar from Theban tomb representations of the eighteenth dynasty,12 and also one much-reproduced scene from the tomb of Ramses III, known as the ‘Harpists’ Tomb’.13 This scene provided the prototype for Ford’s harp, particularly the inclusion of a terminal with a royal crown (in this case the red crown of northern Egypt), and the floral and drop-pendant design on the side of the instrument. However, for the three dimensional form of the harp, Ford may have looked at the smaller portable harps that have survived in which the tip of the harp’s neck often features the head of a falcon, goddess or king.14 Ford, however, opts for an ibis head as his terminal. No harps with such terminals are known, and Ford may have been inspired by bronze ibis-shaped containers for sacred animals displayed in major Western museums since the early nineteenth century.15

Ford’s Singer stands upon a pedestal, guarded by four small caryatid sculptures of standing naked female figures (fig.7). The integration of such figures into Egyptian Revival architecture and interiors predated Ford by at least a century.16 While their headgear is reminiscent of the nemes headdress worn by kings, the trapezoidal feature on top of their heads is not of Egyptian form.

The position of these figures also departs from Egyptian architectural and sculptural norms. In ancient examples, subsidiary figures usually flank a seated figure, or ritual groups of bronze figures (figs.8 and 9). Underneath the pedestal is a plinth, which takes the form of an Egyptian temple, with battered side walls, a cavetto cornice and torus moulding. This architectural form was deployed by Egyptian artists for a range of smaller objects, including funerary pectorals, sacred sistra, and eventually coffins and containers for canopic jars and shabtis, and was a favoured source for architects and artists of various Egyptian revivals.17

Statue of the great royal wife Nefertari, at the side of a colossal enthroned statue of Ramses II, temple of Luxor, 19th dynasty (1290-1224 BC)

Photograph: Neal Spencer

Fig.8

Statue of the great royal wife Nefertari, at the side of a colossal enthroned statue of Ramses II, temple of Luxor, 19th dynasty (1290-1224 BC)

Photograph: Neal Spencer

Copper alloy group showing Isis sucklig Horus-the-child, flanked by figures of Mut and Nephthys, with three uraei at front, Late Period (664-332 BC)

British Museum EA 34954

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.9

Copper alloy group showing Isis sucklig Horus-the-child, flanked by figures of Mut and Nephthys, with three uraei at front, Late Period (664-332 BC)

British Museum EA 34954

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum

The front and back of the plinth bear pharaonic motifs. On the front, a vulture and rearing cobra are paired, representing Nekhbet and Wadjit, the deities of southern and northern Egypt respectively, with the bird’s outspread wings displaying fine plumage on either side (fig.10). In each corner sits a djed pillar, a symbol thought to represent the backbone of the god of the afterlife, Osiris, but one that also invoked notions of endurance and stability. Above all this is a ram-headed vulture holding two shen symbols, which represent the notion of eternal cycles of life. The ram head indicates that this was a representation of Khnum or Amun-Ra, both prominent creator gods.

19th-dynasty Pectoral of Ramses II c.1279–1213 BC

Louvre, Départment des Antiquités Égyptiennes (N767)

Fig.11

19th-dynasty Pectoral of Ramses II c.1279–1213 BC

Louvre, Départment des Antiquités Égyptiennes (N767)

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

902 x 216 x 432 mm

Tate N01753

Presented by Sir Henry Tate 1894

Tate

Fig.12

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

Tate N01753

Tate

Along the top-left of the plinth, the artist’s name is spelt out in phonetic hieroglyphs, followed by a determinative sign depicting a seated craftsman (fig.13):

W-i-A-n-s-l-aA f-i-A-r-d (Onslow Ford)

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

Tate

Fig.13

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail)

Tate

The orientation of these signs opposes that of the serpent, contravening pharaonic practice, revealing that Ford’s understanding of Egyptian artistic conventions was somewhat superficial. Ford’s name is repeated, in reverse orientation, underneath the serpent, and at either side. Here the name reads from top to bottom in the right, but from bottom to top on the left, an orientation never employed in ancient Egypt.

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893

Bronze, silver, enamel and semi-precious stones

670 x 250 x 390 mm

Tate T12622

Presented by Mrs Teresa Fairchild in appreciation of her great-uncle Mr Clinton Thomas Dent, MC, FRCS, who commissioned this work 2008

Tate

Fig.14

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893

Tate T12622

Tate

Granodiorite statue of a royal prince, wearing the sidelock of youth, 19th dynasty (1307-1196 BC)

British Museum EA 68682

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.16

Granodiorite statue of a royal prince, wearing the sidelock of youth, 19th dynasty (1307-1196 BC)

British Museum EA 68682

© Trustees of the British Museum

Scene of fowling in the marshes from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, 18th dynasty, c.1390 BC

British Museum EA 37981

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.18

Scene of fowling in the marshes from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, 18th dynasty, c.1390 BC

British Museum EA 37981

© Trustees of the British Museum

The figure sits on a single plinth, of marble incised with pharaonic motifs and embellished with four silver deities, one at each corner (fig.17). While similar to ancient examples, the slight backwards lean of the deities would have been unusual in an ancient work. On the front, a figure of an ibis-headed god with a male human body stands to one side, wearing a simple kilt, wig and topped with a moon disc and crescent headdress, fronted by another rearing cobra (uraeus). The opposite side features another divine figure, identical in all but the head, in this case that of a falcon. The incised decor on the plinth includes hieroglyphic captions for these deities, with correct orthography, and correlating well with the iconography: Thoth and Khonsu. Further incised decoration includes a tall-stemmed lotus flower on either side of each silver figure, the plant emblematic of northern Egypt. The rear of the plinth bears similar figures, though with silver figures of a cow-headed female god (labelled as Hathor) and a lionness-headed goddess (Sekhmet). The central engraved scene, in both cases, shows two birds hovering over a thicket of papyri (with flowers and unopened buds), with chicks and eggs nestling in the foliage. This motif is also common in eighteenth-dynasty tomb scenes, and invoked notions of natural abundance, fertility and regeneration.23 It was often accompanied by scenes of the tomb owner and his wife fowling or fishing in the marshes (fig.18).

w-n-s-l-w f-r-d (Onslow Ford)

The spacing of the signs, with a marked gap between the ‘w’ and the ‘f’ to indicate the presence of two words, is a feature not known in ancient inscriptions, but the final sign, a figure of a seated man, is a type of sign known as a determinative: it indicated the nature of the preceding word, rather than representing a phonetic value. In this case, it conveys that the words provide the name of a man, showing that Ford had some understanding of the conventions of Egyptian language and its principal script, hieroglyphs, or at least knew someone who did.

The engraved scenes on the left and right of the pedestal of Applause are rather more complex, and identical in composition except for their orientation. In this case, the switch in orientation reflects ancient practice, with the goddess facing in the same direction as the sculpture itself, and the hieroglyphic text mirroring this orientation. In front of the goddess with outstretched vulture wings, brandishing a sceptre and the feather of Maat (embodying the concept of order and justice), a figure is shown seated upon a stool, clapping, keeping time for two registers of musicians to the right; a reference to the main figure in Applause (fig.20).24 The arrangement of figures in two registers is a standard artistic framing device in both temple and tomb scenes. Above, a lady plays a boat-shaped harp. The figure represents an allusion to The Singer, but here the harpist is depicted in a languid pose, in contrast to two-dimensional ancient depictions.25 She is followed by musicians playing a flute or oboe, a lyre and a lute. In the register below, a row of men play a symmetrical lyre, double and single flutes/oboes, a lute and single flute. To the right is an offering stand with a bouquet of flowers draped over it. This type of scene, with an array of musicians playing different instruments, all in slightly different stances that provide a hint of movement and dynamism, is familiar from the decorated tombs of the New Kingdom elite, especially at Thebes.26 However, Ford’s musicians are inspired by these scenes rather than closely copying an ancient example, in contrast to the reproduction of the Louvre pectoral on the base of The Singer.27 That Ford looked at New Kingdom sources is strongly suggested by the finely pleated linen garments of two of the musicians.

The hieroglyphic texts are different on either side of the plinth, and are a faithful copy of a passage from the ‘Harpist’s Song’, perhaps that found in the tomb of Neferhotep, a priest who lived in the reign of Horemheb (c.1319–1292 BC):

[left] Put song and music before you, cast all evil behind you. You think of the joys (fig.21)

[right] until comes that day of mooring at the land that loves silence.(fig.22)28

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail left plinth)

Tate

Fig.21

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail left plinth)

Tate

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail right plinth)

Tate

Fig.22

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail right plinth)

Tate

A translation of this text was displayed alongside Applause when it was first exhibited.29 Neferhotep held the priestly title of ‘divine father of Amun-Ra’, and his finely decorated tomb is decorated with scenes of offerings, guests at a banquet, scenes of the pilgrimage to Abydos and a festival of Sokar. The ‘Harpist’s Song’ is carved on the passage from the outer hall, the text placed above a scene of a squatting harpist before Neferhotep and his wife. First published in 1869,30 translations appeared in the 1870s, including one in the Transactions of the Society for Biblical Archaeology, which may have been the source of Ford’s knowledge, however indirectly.31 The interpretation of these songs varies, as do the different known versions, but they can include reflections on the transitory nature of life, scepticism regarding the eternal afterlife and a suggestion that the present should be enjoyed.32

This plinth scene of Applause is framed with a subdivided border on the top and bottom, a common motif in pharaonic art and architecture, and based on tied bundles of matting. The single column of hieroglyphs at either side of the panel again provide a hieroglyphic rendering of the sculptor’s name (fig.23):

a-i-w-n-s-l-aA f-i-a-r-d (Onslow Ford)

The surname is followed by three signs representing water, and then a small motif depicting a sculptor at work on a standing statue: the determinative sign, telling the viewer – at least those who could read hieroglyphs – that this Onslow Ford was a sculptor. Dozens of ancient signs depict human figures in a raft of occupational poses, so this was a particularly well-informed humorous play on Ford’s metier and the ancient Egyptian language. However, Ford slips up in his orientation of the hieroglyphs, as both feature signs facing to the left: the Egyptian artist would have reorientated the signs to mirror the direction in which the main sculpture faced.

Brightly painted architecture and decoration in the festival hall (akhmenu) of Tuthmosis III at Karnak, 18th dynasty, c. 1450BC

Photograph: Redhead

Fig.24

Brightly painted architecture and decoration in the festival hall (akhmenu) of Tuthmosis III at Karnak, 18th dynasty, c. 1450BC

Photograph: Redhead

Indeed, many ritual bronzes were once heavily gilded, inlaid with precious stones, or inscribed with detailed religious symbolism,33 and Ford’s integration of metalworking techniques, sculpture, relief carving and decorative inlay represents a distant echo of the finest products to come from the ancient temple and palace workshops of pharaonic Egypt. Yet echoing the fate of The Singer, many Egyptian bronzes in museums were overly cleaned, and in one case a cleaned bronze was painted with shades of green and blue, to evoke what a visitor would expect an ancient bronze to look like.34

Notes

For a survey of Egyptian representations of women, see Gay Robins, Women in Ancient Egypt, London 1993.

See ibid.; and also R.B. Parkinson, The painted Tomb-Chapel of Nebamun: Masterpieces of Ancient Egyptian art in the British Museum, London 2008.

Terracotta figures, and ‘Naukratic figures’ shown playing a harp are also preserved, the former displaying significant Hellenistic influence.

Description de l’Égypte ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expedition de l’Armée francaise publié sous les ordres de Napoléon Bonaparte, Paris 1822. On the reception in Britain of this landmark publication, see Andrew Bednarski, Holding Egypt: Tracing the Reception of the 'Description de l'Égypte' in Nineteenth-Century Great Britain, London 2005.

See A. Oppenheim, ‘The Royal Treasures of the Twelfth Dynasty’, in F. Tirradritti, Egyptian Treasures from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Vercelli 1999, pp.136–53. See also the famous Intef diadem, http://www.nicholasreeves.com/item.aspx?category=Collections&id=54 , accessed 27 September 2011.

An exception is a diadem from the tomb of Tutankhamun, http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/carter/256,4,o-p0825.html , accessed 27 September 2011, though this was not discovered until 1922.

Reproduced in colour in the Description de l’Égypte, vol.2, pl.91 and in Ippolito Rosellini, I monumenti dell'Egitto e della Nubia. Vol.2: Monumenti civili, pl.XCVII. Black and white perspective images based on the original tomb scenes can be found in James Bruce, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772, and 1773, 2nd edn, Edinburgh 1805, pls.6,7. Given Ford’s journey to Florence, it is worth noting that the Archaeological Museum there displayed a nineteenth-century gold medallion with a representation of this scene. See M. Cristina Guidotti, Gioielli e cosmesi del Museo Egizio di Firenze, Florence 2003, pp.12–15.

See for example the harp with a human-head terminal in the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=171898&partid=1 , accessed 27 September 2011.

J.-M. Humbert, M. Pantazzi and C. Ziegler, Egyptomania. Egypt in Western Art 1730–1930, exhibition catalogue, Musée du Louvre, Paris 1994, p.40, fig.9, p.71, fig.18.

Des dieux, des tombeaux, un savant. En Égypte, sur les pas de Mariette pacha, exhibition catalogue, Musée du Louvre, Paris 2004, pp.90–1.

Franc¸ois Auguste Ferdinand Mariette, Le Sérapéum de Memphis découvert et décrit par A. Mariette, Paris 1857, vol.3, pl.9.

Philippe Germond, An Egyptian Bestiary: Animals in Life and Religion in the Land of the Pharaohs, London 2003, p.177.

For example see the depiction of princess Nefrura in a statue of Senenmut now in the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=119654&partid=1 , accessed 27 September 2011. See also Catherine H. Roehrig, Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2005, pp.112–16.

See ‘The Statuettes’, in Jason Edwards (ed.), In Focus: Edward Onslow Ford, 'The Singer' exhibited 1889 and 'Applause' 1893, April 2013, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/edward-onslow-ford/the-statuettes-r1141658

Ibid., pp.40–56. See also a stela depicting a festival procession, with the lower register depicting ladies with tambourines, a sistrum and a lyre, their flowing pleated linen garments and poses again suggestive of movement; A. Wiedemann, Das alte Ägypten, Heidelberg 1920, pl.26. One source for such scenes, reproduced in colour, available in the late nineteenth century, was Rosellini’s I monumenti dell'Egitto e della Nubia (Band 4,2, Atlas): Monumenti civili, pls.98–9.

A colour copy of a single register from a tomb at el-Kab with three clappers, a lady with a double flute and a lady with a tall boat-shaped harp was reproduced in the Description de l’Égypte, vol.1, pl.70.

For a translation of the full text, and discussion of its significance, see Miriam Lichtheim, ‘The Songs of the Harpers’, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol.4, no.3, July 1945, pp.178–212. A copy of the hieroglyphs can be consulted in Wilhelm Max Müller, Die Liebespoesie der alten Ägypter, Leipzig 1899, pl.1.

See ‘The Adolescent Female Body’, in Jason Edwards (ed.), In Focus: Edward Onslow Ford, 'The Singer' exhibited 1889 and 'Applause' 1893, April 2013, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/edward-onslow-ford/the-adolescent-female-body-r1141661

How to cite

Neal Spencer, ‘Ancient Egyptian Sources’, April 2013, in Jason Edwards (ed.), In Focus: 'The Singer' exhibited 1889 and 'Applause' 1893 by Edward Onslow Ford, Tate Research Publication, April 2013, https://www