Harold Gilman Edwardian Interior c.1907

Harold Gilman,

Edwardian Interior

c.1907

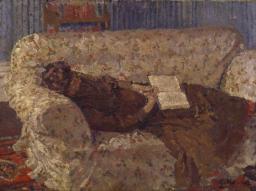

This early work by Harold Gilman takes the domestic interior as its subject. Seated in the corner of the drawing room the painter’s sister Irene faces away from the viewer, her upper body framed by light, leaning forward slightly with hands clasped together. Painted from a high viewpoint, her small figure is dominated by the clutter of objects and patterns surrounding her.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Edwardian Interior

c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

533 x 540 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right and ‘H Gilman 19 Fitzroy St’ in ink on top stretcher bar

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1956

T00096

c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

533 x 540 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right and ‘H Gilman 19 Fitzroy St’ in ink on top stretcher bar

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1956

T00096

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist by Hubert Wellington (1879–1967), from whom bought for £420 by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest in 1956 and presented to Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1943

Paintings and Drawings by Harold Gilman (1876–1919), Lefevre Gallery, London, September 1943 (10).

1957

Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy, London 1957 (721).

1968

In and Around the Slade, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, February–March 1968 (1).

1969

Harold Gilman 1876–1919: An English Post-Impressionist, The Minories, Colchester, March 1969, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, April–May 1969, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, May–June 1969 (11).

1969

The Camden Town Group, Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford, October–November 1969 (11).

1971

British Art 1890–1928, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, February–March 1971 (29, reproduced).

1971

The Slade 1871–1971, Royal Academy, London, November–December 1971 (15).

1987–9

Government Art Collection, 10 Downing Street, July 1987–April 1989 (long loan).

1989

Within These Shores: A Selection of Works from the Chantrey Bequest, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, June–September 1989 (31, reproduced).

2002

Harold Gilman and William Ratcliffe, Southampton City Art Gallery, April–July 2002 (no number, reproduced p.9).

References

1957

Tate Gallery Report 1956–57, London 1957, p.14.

1957

Royal Academy Illustrated, London 1957, reproduced pl.45.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.237.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.124–5, no.12 reproduced.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.169.

2002

Richard Shone, ‘Southampton: Harold Gilman and William Ratcliffe’, Burlington Magazine, vol.144, no.1192, July 2002, p.442, reproduced fig.57.

Technique and condition

Edwardian Interior is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed, stretched, plain, fine-weave linen cloth. ‘H Gilman 19 Fitzroy St’ has been written in ink in bold letters across the top stretcher bar. The canvas retains its selvedge on the right side and is unevenly cut along the three other edges. It is probably sized but no layer is easily visible and the yellowed white priming penetrates through the close weave to the back in places. The priming covers all the canvas, retains the weave texture and appears to have been applied before stretching. It is composed of a single layer of lead white with kaolin and chalk and possible traces of other extenders. This basic type of canvas and preparation is consistent in all of Gilman’s paintings in the Tate collection. It is difficult to ascertain whether Gilman bought canvas, primer and stretchers and primed the length of canvas, cutting it up and stretching it as he required, or if the canvas was purchased ready primed and stretched by the artist onto bought stretchers. It is fair to say, however, that they reflect a consciously economical choice of materials.

The painting was executed over an extended period of time working both wet-in-wet and wet-on-dry paint. No evidence of any preparatory drawing remains visible beneath the multiple layers of paint. The paint is applied in a fairly fluid state and the handling remains clearly visible over most of the surface with its distinct, soft brushmarking and low impasto. Gilman strove to keep the application of new paint as fresh and clean as possible although the many minor modifications he made in adjusting outlines and colours are retained in the topography of the paint surface. Details such as the features of the sitter and contents of the room appear to be secondary to the realisation of the subtle tonality of the fall of light, which is rendered with dextrous application that maintains an even focus across the picture surface. The build-up of multiple layers of paint has resulted in fine contraction cracks and wrinkling in the paint, which are visible in the darkest colours. The painting is covered with a layer of varnish applied over the remnants of earlier varnishes. Some of the earliest varnish may have been applied by Gilman to seal and wet-out earlier work before continuing to paint.

Roy Perry

June 2004

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', June 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘Edwardian Interior c.1907 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Harold Gilman painted this picture at his parents’ home at the Rectory in Snargate, Kent, where his father was the local vicar. Standing next to the church, the Rectory was built in 1891 and first occupied by Gilman’s father. After his father’s death in 1917 it was sold, and so he was the only rector to live there; it has since been known as The Old Rectory.1 The painting shows Gilman’s youngest sister Irene Beatrice Gilman (1877–1944) seated in the drawing room. According to her daughter, Betty Powell, Irene was a frequent model for her brother.2 She also appears in Tate’s Lady on a Sofa (Tate N05831). Irene was apparently Harold’s favourite sister, and they were very close. She was nicknamed ‘The Imp’ by her family, as she was very small, and this explains why it has been thought to be a young girl in this picture, when in fact she was about thirty when it was painted.

There is a group of oriental items on a lacquer cabinet in the corner of the room, including two vases, still in the family’s possession, a bowl and a figure on a stand. These may have been sent back by Gilman’s brother Leofric, who worked in Hong Kong until 1914.3 However, they may have been products of the family’s longer-standing connections with the Far East; Gilman’s grandfather Ellis had founded a tea company in Hong Kong.4 Gilman was often to paint figures turned away in profile, but this extreme example where the figure is virtually facing the wall seems rather strange; it could be that Irene is contemplating the objects. Gilman’s widow Sylvia was unable to identify any of the pictures on the wall, although she wrote that the family ‘had many photographs and early watercolours’.5 However, the picture seen hanging at the top left of Edwardian Interior is Gilman’s own Portrait of a Lady c.1905 (Aberdeen Art Gallery),6 a portrait of his first wife Grace (née Canedy).

The first owner of Edwardian Interior was the artist Hubert Wellington (1879–1967), a friend of Gilman’s from the time they were at the Slade together. He recalled in a letter to the Tate Gallery dated 6 October 1955:

We called the painting ‘Edwardian Interior’ at the Lefevre Exhibition of Gilman’s work in 1943. I think I suggested the title in conversation with [Duncan] Macdonald,7 but there is no doubt that it was painted at Snargate Rectory, and I believe the likeliest date is 1905. I do not think that Sickert knew Gilman in the summer of 1906 and I remember Gore saying at 19 Fitzroy Street in 1907 that Gilman did not know Vuillard’s work. Certainly my picture is the work of a very English ‘intimiste’.8

Sir William Orpen 1878–1931

The Mirror 1900

Oil on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 682 x 580 x 75 mm

Tate N02940

Presented by Mrs Coutts Michie through the Art Fund in memory of the George McCulloch Collection 1913

Fig.1

Sir William Orpen

The Mirror 1900

Tate N02940

Gilman painted such works in a restrained, harmonious palette of browns, greys and blacks sparingly accented with green, pink or blue.15 Essentially it was a formula derived from James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and found in other painters’ work of this time, notably Orpen’s. But in Gilman’s case it was also an effect of his study and copying of Diego Velázquez in Madrid in 1901–2. There was also a certain similarity to Walter Sickert, although Gilman appeared largely unaware of his work until their meeting in 1907.

In his appreciation of Gilman in the catalogue of the 1919 memorial exhibition, Charles Ginner emphasised the qualities that characterise these early works:

He seemed entirely preoccupied with tone values, painting in a low keyed harmony of greys and browns, touched up here and there, in the stronger lights, with ‘arabesques’ of lighter and purer colour, but even these not brought to a very high scale ... Technically the painting of that phase of Gilman’s art is smooth in texture, the different tones are worked into each other according to the more academic and accepted formula ... They reminded one of Alfred Stevens and a little of Whistler and Manet.16

Gilman’s friend Louis F. Fergusson also drew attention to both the surface and stillness of such works:

The pictures were very intimate – very smoothly painted – without impasto – without excrescences. Degas, who disliked anything growing out of a canvas – any thrust of pigment into the third dimension – would have passed his hand over the surface with entire satisfaction. The attitudes of the people represented at their domestic avocations were gravely rendered in an illumination both subtle and subdued; the tones harmonized with impeccable taste.17

Fergusson also drew attention to the debt such works had to the Old Masters, particularly Velázquez and seventeenth-century Dutch painting:

Gilman had a deep reverence for the art of the museums. His visits to the Prado during the summer he spent in Spain impressed him profoundly. In the National Gallery [London] there was one painting he loved to talk of with special affection. It is the portrait of Constanza de Medicis [style of Ghirlandaio]18 ... He loved the Arnolfini Couple [by Jan van Eyck]; and never tired of looking through a book of reproductions of Vermeer of Delft. He would expatiate with enthusiasm on a photograph of the most beautiful thing in Holland – that Head of a Girl in the Mauritshaus [Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring c.1663].19

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

See Harold Gilman and William Ratcliffe, exhibition catalogue, Southampton City Art Gallery 2002, p.9.

T. M.[artin] W.[ood], ‘The New English Art Club’s Summer Exhibition’, Studio, no.47, 1909, p.178; see Richard Thomson, ‘Gilman’s Subjects: Some Observations’, in Arts Council 1981, p.24.

See David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Orpen, Ibsen and the Plays within the Play’, in William Orpen: Politics, Sex and Death, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2005, pp.53–61.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’ in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Ernest Brown & Phillips, The Leicester Galleries, London, October 1919, pp.3–8.

- Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’ in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London: Chatto & Windus 1919, pp.19–32.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Edwardian Interior c.1907 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www