Sketchbooks and Loose Sheets with Designs for Sandycombe Lodge, Twickenham c.1808–12

Sandycombe Lodge, Twickenham: Unexecuted Elevations and Plans c.1809-11

(from the Windmill and Lock sketchbook)

From the entry

The Windmill and Lock and Sandycombe and Yorkshire sketchbooks are grouped together in the present catalogue section since they include significant material relating to the genesis of Sandycombe Lodge, Turner’s small, self-designed house at Twickenham, then in the countryside to the west of London. They also contain drawings and notes addressing various other subjects, as outlined in their respective introductions. Two loose Sandycombe related sheets are also grouped here. There are related drawings in other sketchbooks, as mentioned below. Although Sandycombe is often referred to as part of the biographical narrative in the general Turner literature, the two key accounts are by Patrick Youngblood and Catherine Parry-Wingfield. The author is very grateful to Eric Shanes for the opportunity to see a draft of Sandycombe material from his forthcoming biography of Turner; which has informed this introduction and is acknowledged where relevant. Turner had studied in architects’ offices in his youth, and ...

Sandycombe and Yorkshire sketchbook circa 1809–12 D08965–D09016

Turner Bequest CXXVII 1–37

Turner Bequest CXXVII 1–37

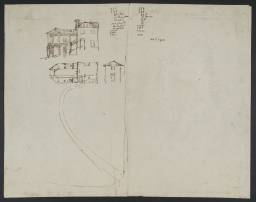

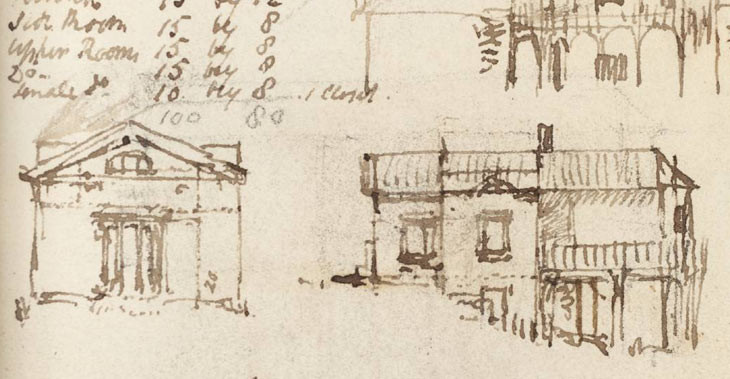

Ground Plan and Elevations of an Unexecuted Design for Sandycombe Lodge circa 1809–12

D08232

Turner Bequest CXX R

D08232

Turner Bequest CXX R

Sandycombe Lodge: The Garden Front as Built and a Sketch Map of the Site at Twickenham circa 1812

D08235

Turner Bequest CXX U

D08235

Turner Bequest CXX U

?Studies for Sandycombe Lodge circa 1812

D40285

D40285

References

The Windmill and Lock and Sandycombe and Yorkshire sketchbooks are grouped together in the present catalogue section since they include significant material relating to the genesis of Sandycombe Lodge, Turner’s small, self-designed house at Twickenham, then in the countryside to the west of London. They also contain drawings and notes addressing various other subjects, as outlined in their respective introductions. Two loose Sandycombe related sheets are also grouped here. There are related drawings in other sketchbooks, as mentioned below. Although Sandycombe is often referred to as part of the biographical narrative in the general Turner literature, the two key accounts are by Patrick Youngblood and Catherine Parry-Wingfield.1 The author is very grateful to Eric Shanes for the opportunity to see a draft of Sandycombe material from his forthcoming biography of Turner;2 which has informed this introduction and is acknowledged where relevant.

Turner had studied in architects’ offices in his youth, and designed his own gallery at Queen Anne Street in central London; he is also traditionally supposed to have designed classical gatehouses at Farnley Hall, home of his Yorkshire friend and patron Walter Fawkes.3 It is now generally accepted that he designed and supervised the construction of Sandycombe Lodge himself. The artist had previously rented homes on the Thames up-river from London, at Isleworth and Hammersmith.4 He may have been partly motivated to build a house in the vicinity to project his growing status as a Royal Academician, but also intended it as a home for his ageing father, who was approaching sixty at this time and had acted for some time as his son’s assistant.5

Turner regarded the Thames west of London with a reverence founded on its associations with favourite poets such as James Thomson and Alexander Pope; he often sketched and painted the Thames in its modern aspect and also as an inspiration for classical compositions.6 Two drafts of Turner’s own poetry, concerning Alexander Pope and his recently demolished Twickenham home, are in the Windmill and Lock sketchbook, included in this Sandycombe section (Tate D07964, D08064; Turner Bequest CXIV 4, 77). Another of his heroes, Sir Joshua Reynolds, the President of the Royal Academy, had lived on Richmond Hill, with its famous view west across the Thames meadows to Twickenham and beyond as shown in Turner’s ambitious and evocative painting England: Richmond Hill, on the Prince Regent’s Birthday, exhibited in 1819 (Tate N00502).7

Sandycombe Lodge still stands in Sandycoombe Road (sic), between St Margaret’s Road and St Stephen’s Gardens in Twickenham, about half a mile from the Thames at the focus of the long bend of the river separating Twickenham from Richmond upon Thames to the east, with the grounds of Marble Hill House and Orleans House close by towards the river to the south.8 The present owner, from 2010, is the Sandycombe Lodge Trust, supported by the Friends of Turner’s House, a group established in 2004 to support Professor Harold Livermore (1914–2010), by then the owner for many years (with his late wife Ann) ‘in his aim to preserve the house for the nation’.9 The house itself is briefly described in the course of this introduction.

Youngblood has traced the deed recording the sale (but not the price) of the land to Turner by a John Baker ‘of Lower Grosvenor Street’, central London, on 4 May 1807 (London Metropolitan Archives, formerly Greater London Record Office), with its location being described as ‘Sand Pit Close’, which perhaps influenced Turner’s eventual choice of name.10 He also bought a ‘small meadow’ nearby from the same vendor.11 Other records in the same archives show that he was awarded a small piece of land nearby when Twickenham was enclosed in 1818, and bought three neighbouring plots, the prospective site of the artists’ charity which caused so much contention in his will.12

The documentation relating to Sandycombe is ‘meagre’,13 and Turner’s notes are typically widely dispersed through his sketchbooks and fragmentary. An entry of ‘400 Richmond’ on a loose sheet in the Finance sketchbook (Tate D40900; verso of CXXII (4)), interpreted by Finberg as the cost of the land,14 probably refers instead to the value of the oil of Richmond Hill and Bridge, exhibited in 1808 (Tate N00557);15 however, the entry ‘B. Sandycomb 400’ in the Guards sketchbook (Tate D13260; Turner Bequest CLXIV 13a) may reflect the cost of construction.16 In the Sandycombe and Yorkshire sketchbook, the note ‘400 Purchase’ in a list of estimated costs including ‘400 Building | 100 Grounds’ (Tate D08967; Turner Bequest CXXVII 3) may refer to the land, as could two unexplained figures of ‘390’ elsewhere, perhaps indicating a discount, whether sought or actual (Tate D08232; Turner Bequest CXX R);17 ‘400 Building’ in the same Sandycombe and Yorkshire list may be an estimate of construction costs,18 while apparent rates for labour are given in the Lowther sketchbook (Tate D07872; Turner Bequest CXIII 13).19

The dating of the various site plans, ground plans and elevation designs for the house may potentially range from spring 1807 to 1812. Eric Shanes has suggested the main design campaigns as between ‘the summer of 1809 and the early autumn of 1811’,20 and these year dates have generally been adopted for the relevant works in the present section; he further suggests that Turner was ready to produce a ‘master plan’ when he visited Farnley Hall in November 1811, and perhaps commissioned an architectural draughtsman for this purpose (see under Tate D08967; Turner Bequest CXXVII 3).21 Youngblood mentions up to eight sketchbooks, and over twenty plans and over forty elevations,22 many of which are quite slight and indefinite. He has identified what seems to be an early, rough plan of the site in the Derbyshire sketchbook (Tate D07188; Turner Bequest CVI 48a).23 One of the loose drawings grouped with the Sandycombe material in the present catalogue (Tate D08235; Turner Bequest CXX U) combines a site plan with the garden elevation of the house more or less as built, and may be from 1812.24 Another site plan, in the Sandycombe and Yorkshire sketchbook (Tate D08994; Turner Bequest CXXVII 21a), shows the garden in some detail, and may be from a similar date, although the plan of the house is not as built.25

The incidental dates 17 January and 26 February 1812 on the page in the Yorkshire and Sandycombe sketchbook already mentioned (D08967; CXXVII 3), which also comprises various costs and a far from resolved plan of the house, together with the many alternative designs elsewhere in the sketchbook, have caused Youngblood to speculate that ‘the house was not begun until the spring of 1812 or later’, although the only absolute date is July 1813, when Turner was ‘first rated for the house’.26 He notes that the diversity of the scattered designs for the house makes dating them problematic, although ‘compactness and symmetry’ are the main characteristics,27 with competing ‘rustic’ or ‘Palladian’ (classical) characteristics.28

Youngblood’s comments on particular studies are noted as appropriate under individual entries here. He categorises Turner’s plans as broadly ‘Type A’, with a narrow frontage but running comparatively deep west-east over the slope in the site’s garden, and ‘Type B’, with a broad frontage along the road but not advancing so far into the garden;29 as he notes, many plans of both types have a ‘semi-hexagonal bay’ on the garden front, an idea which may have contributed eventually to the chamfered north and south wings as built.30 Youngblood sees a drawing in the Windmill and Lock sketchbook (Tate D08075; Turner Bequest CXIV 82a) as combining the ‘salient characteristics’31 of the both types in something approaching the plan of the house as built, albeit with two-storey wings rather than the single-storey ones originally built. A page of plans and elevations in the Woodcock Shooting sketchbook (Tate D09128; Turner Bequest CXXIX 51a) also seems to have contributed to this synthesis.32

In 1813 Turner gave the address as ‘Solus Lodge’, perhaps to emphasise its relative isolation, but soon changed it to the present form.33 He lived there for a relatively short period, and even then not all the time due to his many professional commitments; he retained his central London house with its studio and gallery and undertook his habitual frequent tours, selling Sandycombe in 1826, as noted below.34 His only comment on the house, in a letter of 1 August 1815, was that it ‘sounds just now in my ears as an act of folly, when I consider how little I have been able to be there this year’.35

At the core of the brick-built house is a compact two-storey block with shallow gables on the west and east fronts, with one main room on the ground floor, looking east, a large bedroom (for Turner) above with the same aspect, and a smaller bedroom (for Turner’s father) above the front door on the west side, set back a short distance from the road.36 The house overlooked a long, tapering garden sloping down to its east, with a Diocletian (semi-circular) basement window set within the slope. To the north and south, small wings with chamfered corners and projecting Tuscan-style were originally single-storey, but were built up at an unknown date, most likely after Turner’s occupancy, almost to the height of the central block, while retaining the wide eaves and low rooflines of the original design; the stucco finish is typical of Italianate villas of the period.37 The garden (east) front of the house is shown in a watercolour of about 1814 by William Havell (private collection);38 apart from obvious alterations, the house appears much the same today, although Havell’s artistic licence (and no doubt Turner’s wishful thinking) shows it too close to the river,39 and the extensive garden plot is now largely built over along its north-eastern and south-eastern perimeters. There is an engraving after Havell’s design (Tate T06433).40

As with other features, the chamfered wings with inset panels were probably influenced by examples in architectural pattern books of the time, and possibly by the domestic buildings of the architect (Sir) John Soane, Turner’s friend and Royal Academician,41 while prominent triglyph motifs may echo those in Henry Carr of York’s work of about 1790 at Fawkes’s Farnley Hall.42 Various motifs could have been taken from Asgill House, by Sir Robert Taylor (1758–67),43 which overlooks the Thames at the end of Old Palace Lane, Richmond, opposite Twickenham. The interior also appears much influenced by Soane,44 who may have taken an interest in Turner’s project – as Eric Shanes has noted, Turner dined with Soane on the very day in May 1807 when he acquired his Sandycombe land.45 The only identifiable drawing relating to it, in the Woodcock Shooting sketchbook (Tate D09204; Turner Bequest CXXIX 122) shows variations on a fireplace with fluting and roundels resembling the one built in the main sitting room.46

Turner sold the house in 1826 for £500, though he possibly retained the ‘small meadow’, and kept the nearby land which he had in mind for his artists’ charity. The main motive for the sale was probably his elderly father’s failing health and consequent difficulty in maintaining keeping the garden up and regularly travelling the eleven or so miles to Turner’s central London house.47

There are a few scattered drawings relating (or possibly relating) to Sandycombe in other sketchbooks. These include: rough ink elevations in the Hastings sketchbook (Tate D07596; Turner Bequest CXI 2); an ink view of a Sandycombe-like house in a wooded landscape in the 1811 Devonshire Coast, No.1 sketchbook (Tate D08801; Turner Bequest CXXIII 247a); a tentative if elaborate plan of a tapering garden and an associated topographical view in ink in the Woodcock Shooting sketchbook (Tate D09075 Finberg number: CXXIX 14v), which contains other Sandycombe drawings mentioned in the course of this introduction. Finally, a very slight pencil elevation of a symmetrical house (Tate D41516) on the verso of Turner’s Liber Studiorum watercolour design for Glaucus and Scylla (Tate D08170; Turner Bequest CXVIII P) may be an idea for Sandycombe.

See Youngblood 1982, p.20; see also James Hamilton, ‘Architect, Turner as’ in Joll, Butlin and Herrmann 2001, pp.9–10.

See Youngblood 1982, p.34 note 9; see also David Hill, Turner on the Thames: River Journeys in the Year 1805, New Haven and London 1993.

Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, revised ed., New Haven and London 1984, pp.106–7 no.140, pl.145 (colour).

Friends of Turner’s House, accessed 28 November 2011, http://www.turnershouse.co.uk ; see also Parry-Wingfield 2006, p.25.

Alexander J. Finberg, The Life of J.M.W. Turner, R.A. Second Edition, Revised, with a Supplement, by Hilda F. Finberg, revised ed., Oxford 1961, p.192.

John Gage, Collected Correspondence of J.M.W. Turner with an Early Diary and a Memoir by George Jones, Oxford 1980, p.61 letter no.56, as partly quoted in Youngblood 1982, p.20.

See Youngblood 1982, ill.4; there are no published scale plans or elevations of the house, or published views of the garden front.

How to cite

Matthew Imms, ‘Sketchbooks and Loose Sheets with Designs for Sandycombe Lodge, Twickenham c.1808–12’, January 2012, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www