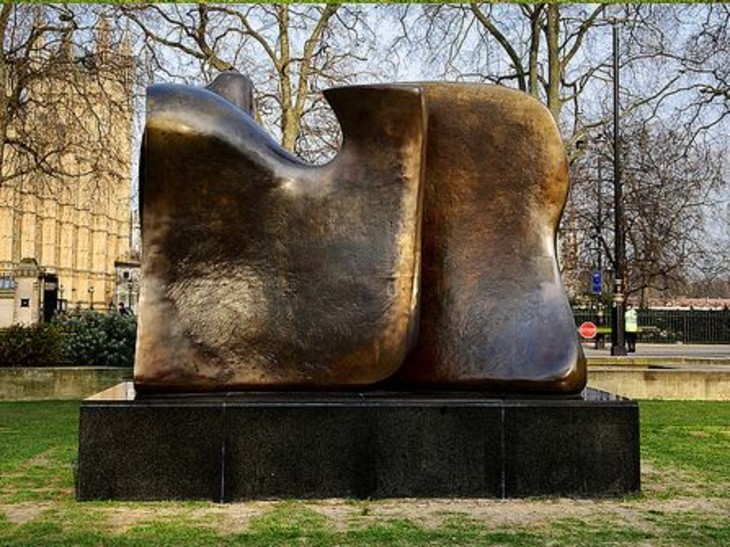

Henry Moore OM, CH Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Image 1 of 10

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece

1962, cast 1963

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece served as the model for a monumental version of the sculpture completed in 1965. It is representative of Henry Moore’s re-engagement with abstraction in the 1960s, exploring qualities of thinness and broadness inspired by the shapes of bones.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece

1962, cast 1963

Bronze

498 x 711 x 330 mm

Purchased 1963

Number 5 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T00603

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece

1962, cast 1963

Bronze

498 x 711 x 330 mm

Purchased 1963

Number 5 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T00603

Ownership history

Purchased from Marlborough Fine Art (Grant-in-Aid) in 1963.

Exhibition history

1963

Henry Moore: Recent Work, Marlborough Fine Art, London, July–August 1963, no.14 (as Sculpture, Knife Edge Two Piece).

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.125.

1969

Henry Moore, Heslington Hall, York, March 1969 (?another cast no.31).

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, September–November 1973, no.43.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.39.

References

1963

Henry Moore: Recent Work, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1963, reproduced.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.244 (Knife Edge Two Piece reproduced pl.235).

1967

Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International, vol.11, no.7, September 1967, pp.42–5.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, pp.61, 228 (Knife Edge Two Piece reproduced pp.228–9).

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1973, reproduced p.53.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.48.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced p.95.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, reproduced p.186.

2005

David Mitchinson (ed.), Henry Moore and the Challenge of Architecture, Much Hadham 2005 (another cast reproduced p.31).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (Knife Edge Two Piece reproduced p.78).

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.277–9.

2010

Gregor Muir (ed.), Henry Moore: Ideas for Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Hauser & Wirth, London 2010 (another cast reproduced p.157).

2011

John Paul Stonard, ‘Henry Moore’s “Knife Edge Mirror Two Piece” at the National Gallery of Art, Washington’, Burlington Magazine, vol.153, April 2011, pp.249–55.

Technique and condition

This sculpture is formed of two thin, upright pieces of bronze, each attached by two bolts to a rectangular bronze base. Moore would have made the original model for this sculpture by building successive layers of wet plaster over a supportive armature probably constructed from wood. When the plaster had hardened its surface was smoothed with various files and abrasive papers before the finished model was transported to the Art Bronze Foundry in London. At the foundry a mould would have been taken from each section of the original plaster and used to make a cast of the sculpture in bronze. Fine abrasives were applied to the bronze sculpture and its base after they were cast to produce the smooth, reflective surfaces. As a result of this process it is difficult to ascertain whether the sculpture was cast using the lost wax casting method or the sand casting technique.

Detail of patina on Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of patina on Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

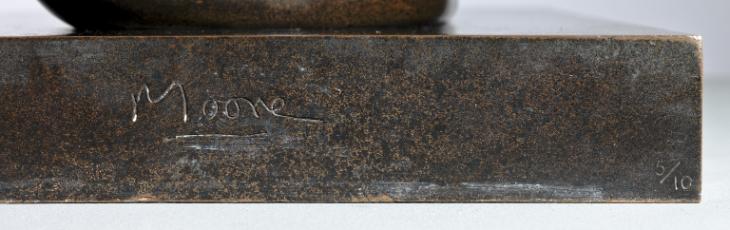

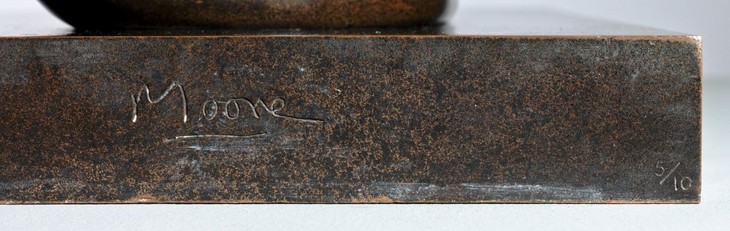

Detail of signature and edition number on base of Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of signature and edition number on base of Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After it had been cast and finished the sculpture was artificially patinated. This process involved applying chemical solutions to the surface that reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. The sculpture’s dark brown patina has a speckled appearance suggesting that the solutions were sprayed rather than brushed onto the surface (fig.1). The patina was then rubbed back on the high points, allowing the more golden tones of the bronze to shine through. The base is patinated an even darker brown and its edges have also been rubbed back to reveal golden-brown highlights. The surface was then lacquered to prevent the exposed bronze from oxidising. The artist’s signature, ‘Moore’, is inscribed on one edge of the base, in the lower right corner of which the edition number ‘5/10’ is stamped (fig.2).

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece is an abstract bronze sculpture comprising two thin, irregularly shaped forms positioned next to each other on a bronze base in an almost parallel arrangement. From most angles the curvilinear edges of each form overlap, so that different configurations are established when seen in the round. Moving around the sculpture in this way reveals that the breadth of the two forms is emphasised from the longer sides of the sculpture (fig.1), while their thinness and verticality are enhanced from the two shorter sides (fig.2). The elliptical gap between the forms can be seen from two of the corners, which also reveals some surfaces to be slightly concave (fig.3).

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963 (side view)

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963 (side view)

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The larger of the two pieces features a prominent rounded notch cut into its upper edge that curves up to a tall, sharp-tipped spur with a flat top (fig.4). This end of this form drops smoothly down to the base, whereas the other end splits into two planes separated by a deep fissure. One is thinner and slightly taller with a more curvaceous vertical face, while the other is thicker with a sheer flat face. An oval-shaped projection emerges from the side of the more curvaceous form and marks the tallest part of the sculpture (fig.5).

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The surfaces of the smaller piece are similarly smooth and feature analogous curved faces and clean-cut edges but no protrusions (fig.6). From the outer edge it rises from a wider, rounded swelling at the base before narrowing as it extends upwards towards the mid-point, from which it remains a consistent width to the top edge. The overall width of the piece thins progressively into a blade-like, curved inner edge with a pointed tip that echoes the sharp angle of the spur behind it (fig.7).

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963 (corner view)

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963 (corner view)

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of blade-like points of Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Detail of blade-like points of Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

By the time Moore made Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece in 1962 he rarely made preparatory drawings for his sculptures. Instead he preferred to test his sculptural ideas in three dimensions from the outset by making small models or maquettes from plaster or other malleable materials. It is probable that this sculpture originated from a maquette, most likely made in the small sculpture studio on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. This studio was lined with shelves displaying Moore’s ever growing collection of found bones, shells and flint stones, the shapes of which often served as starting points for Moore’s formal experiments in three dimensions. In 1963 he described to the critic David Sylvester how these natural objects informed his work:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press them into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.1

It is likely that Moore developed the maquette for Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece in just this way, taking a plaster cast from the impression left by one or more bones in a piece of clay. As the plaster hardened Moore could add and subtract forms, and smooth or sharpen edges and points as he wished. Moore would then have used the finished plaster maquette as a template for Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece. By systematically charting and measuring specific points on the surface of the maquette, an armature for the larger sculpture could be made to a precise size. It is likely that the armature for this sculpture was made with wood and possibly chicken wire by one of Moore’s assistants, who in 1962 were Geoffrey Greetham, Robert Holding, Clive Sheppard, and Isaac Witkin.2 Lengths of scrim, a bandage-like fabric, would have been soaked in wet plaster and stretched between the individual struts of the armature. Once dry the scrim and plaster formed an outer shell onto which thicker layers of plaster could be applied.

After the plaster had been built up to the required depth Moore and his assistants then worked into the surface using an array of tools including chisels, files and sandpaper. These tools could be used to produce a variety of textures depending on the consistency of the plaster as it dried, which were in turn reproduced in the cast bronze. In 1977 the curator Alan Bowness noted that ‘most of the post-war bronzes had rough, variegated textures’, whereas from the early 1960s ‘Moore began to introduce smooth and polished bronze surfaces’.3

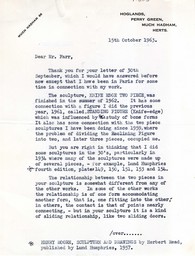

In October 1963 Moore responded to a query about the origins of this sculpture from Dennis Farr, Assistant Keeper of the Tate collection, by stating that ‘Sculpture (Knife Edge Two Piece) was finished in the summer of 1962’.4 According to records held in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive Tate’s bronze was cast in February 1963. Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece is not stamped with a foundry mark, although it is known to have been cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London.5 While the finely polished surfaces of this sculpture provide no definitive evidence as to whether it was cast using the lost wax or sand casting method, in either case the foundry technicians would have taken a hollow mould from the plaster original into which molten bronze could be poured.

After the bronze sculpture had been cast at the foundry its surface was artificially patinated. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. The brown patina of Tate’s Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece has a speckled appearance with darker and lighter tones (fig.8). The darker patina was probably evenly applied and then rubbed back on the high points, allowing the lighter tones to shine through. A coat of protective lacquer has been applied to the surface to prevent these lighter areas from oxidising and changing colour.

Detail of patina on Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of patina on Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963

Tate T00603

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Knife Edge Two Piece 1962–5

Bronze

Palace of Westminster, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Knife Edge Two Piece 1962–5

Palace of Westminster, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece marked the intermediary stage in the development of a much larger version of the sculpture. In 1963 Moore stated that ‘in my mind the final size of your [Tate’s] sculpture was meant to be well over life-size, ten or twelve feet high, so that a person could have walked along the length of the sculpture between the two forms – but it is not always possible to carry out everything in its intended full size – there just isn’t time’.6 However, Moore did eventually manage to commence work on the larger Knife Edge Two Piece. Moore’s assistants would have used the same procedures by which they enlarged the maquette to scale up the plaster working model and cast the resulting full-size plaster in bronze. The full-size Knife Edge Two Piece 1962–5 stands at 275 cm and was cast in an edition of three. One of these casts is positioned outside the Houses of Parliament in London, where it was unveiled in November 1967 (fig.9). The two other casts are held in Queen Elizabeth Park, Vancouver, and the Kykuit Rockefeller Estate, New York.

Sources

In his October 1963 letter to Dennis Farr Moore stated that Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece:

has some connection with the figure I did the previous year, 1961, called, ‘Standing Figure (Knife-edge)’ which was influenced by the study of bone forms. It has also some connection with the two piece sculptures I have been doing since 1959, where the problem of dividing the Reclining Figure into two, and later three pieces, occupied me.7

Standing Figure Knife Edge 1961 (fig.10) is an abbreviated representation of a standing human figure featuring a rounded protrusion at the top denoting a head, and a diagonal ridge half way up the sculpture that occupies the position of the waist. The main body of the sculpture comprises two vertically orientated, blade-like surfaces, creating what Moore described in 1966 as a ‘knife-edged thinness throughout a whole figure’.8 He also noted that bones provided the starting point for this sculpture:

Since my student days I have liked the shape of bones, and have drawn them, studied them in the Natural History Museum, found them on sea-shores and saved them out of the stewpot ... Some bones, such as the breast bones of birds, have the lightweight fineness of a knife-blade. Finding such a bone led to me using this knife-edge thinness in 1961.9

Henry Moore

Standing Figure Knife Edge 1961

Bronze

Yorkshire Sculpture Park

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Standing Figure Knife Edge 1961

Yorkshire Sculpture Park

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Winged Victory of Samothrace c.220–185 BC

Musée du Louvre, Paris

© Erich Lessing

Fig.11

Winged Victory of Samothrace c.220–185 BC

Musée du Louvre, Paris

© Erich Lessing

Moore also identified other reference points for Standing Figure Knife Edge. In 1966 he stated that ‘in a sculptor’s work all sorts of past experiences and influences are fused and used – and somewhere in this work there is a connection with the so-called Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre [fig.11] – and I would like to think that others see something Greek in this Standing Figure’.10 In 2008 the artist’s daughter Mary Moore proposed that traces of Winged Victory of Samothrace – a second-century BC Greek sculpture of Nike, the goddess of victory – could also be found in Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece:

What you have to remember here is that my father’s imagining you moving around it, and that as you do, what you see changes entirely. If you start with a sideways view, what you have in front of you is a wide, panoramic form. Then if you move around it and see it end on, this is reduced to a very narrow form, and of course that’s mirrored in this sharp sickle form in the second piece. What’s really thrilling about it is that combination of sharpness and then the very broad expansive nature of it. My father loved the Winged Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre because of this very sense of broad and then the narrow as you move.11

With this in mind Mary Moore may have been echoing her father’s belief that ‘sculpture has some disadvantages compared with painting, but it can have one great advantage over painting – that it can be looked at from all round; and if this attitude is used and fully exploited then it can give to sculpture a continual, changing, never-ending surprise and interest’.12

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The relationship between the two pieces in your [Tate’s] sculpture is somewhat different from any of the other works. In some of the other works the relationship is of one form accommodating another form, that is, one fitting into the other; in others the contact is that of points nearly connecting, but in your sculpture it is a kind of sliding relationship, like two sliding doors.13

Moore had experimented with multi-part sculptures in the 1930s in order to explore the ways in which parts of a sculpture interacted with each other, simultaneously breaking and binding the space around them. He resumed these experiments in the 1960s, exploring the potential of adjacent parts to not only touch but interlock. As Moore noted, this is not the case with Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece, in which the gap between the two parallel pieces appears instead to open and close when viewed in the round, which may account for Moore’s likening of the sculpture to ‘two sliding doors’. This analogy appears to have gained currency in that it was used by the critic Albert Elsen in 1967 when he discussed the full-size bronze under the title Sculpture, Knife Edge-Sliding Piece.14

Acquisition and critical reception

This cast was purchased by Tate in 1963 through Moore’s commercial gallery Marlborough Fine Art for £3,500.15 Between July and August that year the sculpture had been displayed under the title Sculpture, Knife Edge Two Piece at Marlborough’s London premises, where it was probably seen by the Tate’s director John Rothenstein. Correspondence held in the Tate Archive reveals that Rothenstein enquired about the price of the sculpture and received a reply from Marlborough’s director Harry Fischer on 15 July 1963. Fischer stated that ‘the edition of “Two-Piece – Knife Edge” has been sold out, with the exception of two copies, one of which is reserved and the other Henry is prepared to let the Tate have for £3,500 on which we would make a 15% commission. The last remaining copy for sale in the exhibition is £5,000’.16 On 18 July the proposed acquisition was discussed and agreed by the Tate’s Board of Trustees, and in a letter to Moore the next day Rothenstein wrote, ‘I understand from the Marlborough that we owe the reduction in price mainly to your generosity. It is a splendid work and we are all delighted to see it added to the collection’.17

Although the catalogue for the Marlborough exhibition implied that it was a solo show, the gallery space was in fact shared between Moore and the painter Francis Bacon.18 Writing in the Observer the critic Nigel Gosling observed at the time that ‘any exhibition pairing Henry Moore and Francis Bacon is sure to be a hit’.19 After commenting on the inventiveness of Moore’s recent work, Gosling went on to identify the ‘superbly finished’ Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece as ‘intriguing’.20 Meanwhile the critic Joseph Rykwert asserted that ‘Knife Edge, Two Pieces is remarkable for the brilliant subtlety in the relationship of the two shapes and the great tonal beauty of the material’.21 David Thompson echoed this sentiment in the Times, writing that in ‘smoothing and polishing the surface of his bronzes as he has not done for a long time, [Moore] seems to recall something of his finest carvings in polished stone of the 1930s’.22 Thompson concluded that the sculpture was ‘remarkable not only for its flow of surface and contour but in the exceptional beauty in its patina’.23 Conversely, but with equal praise, the curator Bryan Robertson identified something menacing about Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece:

The knife-edge forms, the three-piece reclining figure ... the locking piece and the knife-edge two-piece confrontation are all brilliant and forceful inventions. The essence of Moore’s work is always to be found in his grimmest or most ferocious sculpture; his matronly figures and other sweeter preoccupations lack the conviction and the formal power of his darker side.24

Although Moore’s non-figurative sculptures of the 1960s were considered to be innovative at the time, there is a paucity of critical analysis on Moore’s work from the mid-1960s onwards.25 In his posthumously published book on Moore, which appeared in 1993, the critic Peter Fuller sought to provide some explanation for this, suggesting that ‘Moore’s monumental vision was widely held to be irrelevant in a world of obsolescence, consumer durables, admass and information processing, as was his continued use of traditional means and materials of the sculptor: modelling and carving, marble and bronze’.26 Rather than submit individual works to genuine analysis, many critics, including those supportive of Moore’s work, described these sculptures collectively as part of a ‘late bronze period’ characterised by smooth stylised forms.27

Installation view of the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Installation view of the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece was cast in an edition of ten plus one artist’s proof. The base of Tate’s cast is stamped with the number ‘5/10’. According to records held at the Henry Moore Foundation the original plaster was destroyed. Other casts of Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece are held in the National Trust for Historic Preservation, USA; Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester; Stuyvesant Foundation; Arts Council of Great Britain; Gemeentemuseum, The Hague; Didrichsen Art Museum, Helsinki; the British Council; Kunsthaus, Zurich; and the Henry Moore Family Collection.

Alice Correia

October 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester, ‘Henry Moore talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7).

In 1968 Moore explained that ‘at one time I used wire netting in making the armature, but this caused immense trouble when I made alterations which are always necessary in enlarging the maquette into a full size sculpture. Now for the armature I use only wood struts and scrim, a form of open sacking’. Henry Moore cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.345.

Henry Moore, letter to Dennis Farr, 15 October 1963, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23945.

Mary Moore, ‘Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece’, in Gregor Muir (ed.), Henry Moore: Ideas for Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Hauser & Wirth, London 2010, p.156.

Albert Elsen, ‘The New Freedom of Henry Moore’, Art International, vol.11,no.7, September 1967, pp.42–5.

Tate also acquired Bacon’s Study for Portrait on Folding Bed 1963 (Tate T00604) from this exhibition.

Joseph Rykwert, ‘Moore a Londra’, Notiziario: Arte Modern, September 1963, Henry Moore press cuttings, 1963, Tate Archive.

Related essays

- Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions Pauline Rose

- Henry Moore’s Photographic Identity Marin R. Sullivan

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore Courtney J. Martin

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Knife Edge Two Piece 1962, cast 1963 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www