Henry Moore OM, CH Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3

Image 1 of 13

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Upright Internal/External Form

1952-3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Upright Internal/External Form was one of the first large-scale sculptures Moore made out of plaster, and is the original version of a work that was also subsequently made in elm and bronze. Its subject relates to Moore’s interest in protective armoury and embryonic growth, while its formal origins can be traced to Moore’s wartime drawings.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Upright Internal/External Form

1952–3

Plaster on a wooden plinth

1956 x 679 x 692 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02272

Upright Internal/External Form

1952–3

Plaster on a wooden plinth

1956 x 679 x 692 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02272

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977, no.61.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.9.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

2010

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010, no.130.

References

1954

David Sylvester, ‘Henry Moore’s Sculpture’, Britain Today, no.215, March 1954, pp.32–5.

1955

Recent Sculpture and Early Life Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1955 (elm version reproduced p.2).

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, pp.126–7, reproduced pl.104.

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, reproduced pls.25–25a.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.182–6.

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.247.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.121.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.85.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.131, 198.

1975

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1975, pp.143–7.

1977

Kenneth Clark, Henry Moore Drawings, London 1974, pp.113–20 (elm version reproduced p.139, no.124).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977, reproduced p.98.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.29.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, pp.116–17.

1981

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Henry Moore and Surrealism’, Burlington Magazine, vol.123, no.944, November 1981, pp.644–58.

1984

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’ in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, vol.2, pp.595–614.

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.138–9 (bronze working model reproduced p.128).

1996

Henry Moore: L’expression première, exhibition catalogue, Musée des Beaux Artes, Nantes 1996, reproduced p.123.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998 (bronze cast reproduced p.183).

1998

Henry Moore: Friendship and Influence, exhibition catalogue, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich 1998 (bronze cast reproduced p.14).

2000

Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000 (plaster cast reproduced no.11).

2001

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Moore: A Modernist Primitive’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, pp.33–41.

2002

Henry Moore: Rétrospective, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul 2002, reproduced p.138.

2006

Gail Gelburd, ‘Large Upright Internal/External Form’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.230–1.

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006 (plaster cast reproduced p.135).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (elm version reproduced p.62).

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.190.

2012

Evelyn Silber, ‘The Leicester Galleries and the Promotion of Modernist Sculpture in London, 1902–1975’, Sculpture Journal, vol.21, no.2, 2012 (elm version reproduced p.141).

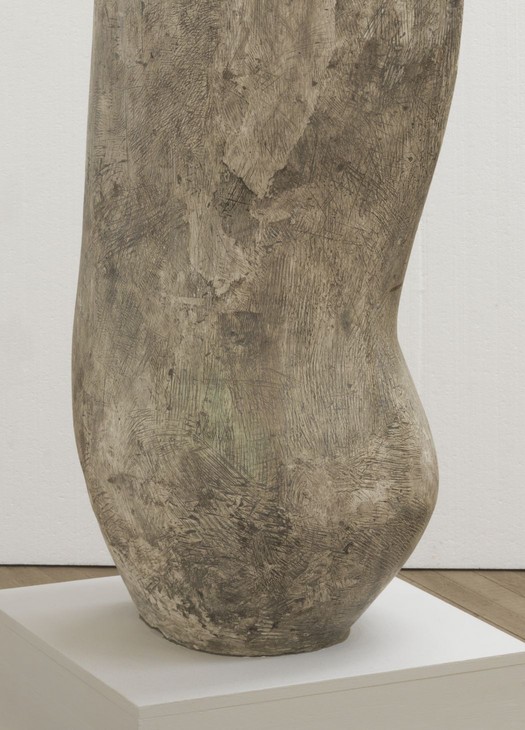

Technique and condition

This large plaster sculpture comprises a thin, vertically-orientated figure surrounded by an outer cocoon-like form. The cuboid wooden plinth on which it sits is fitted with four steel bolts that secure the sculpture in place. The plinth is now painted grey but the underside is painted silver, which suggests that this may have been its original colour.

Detail of interior bolt in Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of interior bolt in Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of interior bolt in Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of interior bolt in Upright Internal/External Form 1952-3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The figure at the centre of the sculpture is held in place at its base by plaster but it is also secured to the outer form by two supporting screw threads. One joins the back of the figure’s ‘head’ to the interior of the cocoon at the back (fig.1), and another fixes the upper rounded form of the internal form to an adjacent point on the interior wall (fig.2), although this is obscured from the viewer by the strip of plaster projecting across the front of the sculpture. A great deal of damage has occurred to the outer form where it joins the base, presumably as a result of stresses applied to this point during transit and handling.

Moore initially made this plaster so that a mould could be made from it that could be used to cast the sculpture in bronze. To make a plaster of this size he would first have constructed a supportive armature, probably using a combination of metal and wood. He would have then applied successive layers of wet plaster to it, gradually building up the form before finishing it with a striated surface texture. Close examination reveals the presence of small metal or wooden points lying just under the surface of the plaster (fig.3). It seems that a number of outward-facing, pointed rods were attached to the main body of the armature, marking at various points the desired depth of the sculpture’s outer form as Moore built up the plaster. This would have been part of the process of scaling up the sculpture from one of Moore’s smaller models, allowing the proportions of the original form to be accurately replicated in the plaster.

When a mould is taken from a plaster in order to cast it in bronze a release agent is applied that enables the mould to be removed from the sculpture while retaining as much surface detail as possible. Traces of release agent remain visible on certain areas of the sculpture’s surface in the form of yellow-brown patches, marking the position where two edges of the mould met (fig.4).

Detail of Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 showing yellow-brown area

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 showing yellow-brown area

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of repair to arch on Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of repair to arch on Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Large or complex plasters such as this will often be cut into parts during the casting process, with the resulting pieces of bronze being welded together after casting. There appears to be evidence of this in the form of vertical cuts made on either side of the arch that projects across the open face of the sculpture (fig.5). There also seem to have been two sets of horizontal cuts made at around one and fourth fifths of the sculpture’s height respectively. Numerous repairs have been made to the surface following damage caused by the moulding process. Moore asked for the plaster to be reassembled after the casting was complete and it is likely that most of the repairs were carried out at this point.

A fine wash of brown pigment has been applied to the surface of the sculpture, adding tone to the whiteness of the plaster and highlighting its surface texture. It seems likely that the pigment was applied after casting, perhaps so that the plaster could be seen and exhibited as a finished sculpture in its own right rather than as a preliminary stage of the casting process. There is no signature visible.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

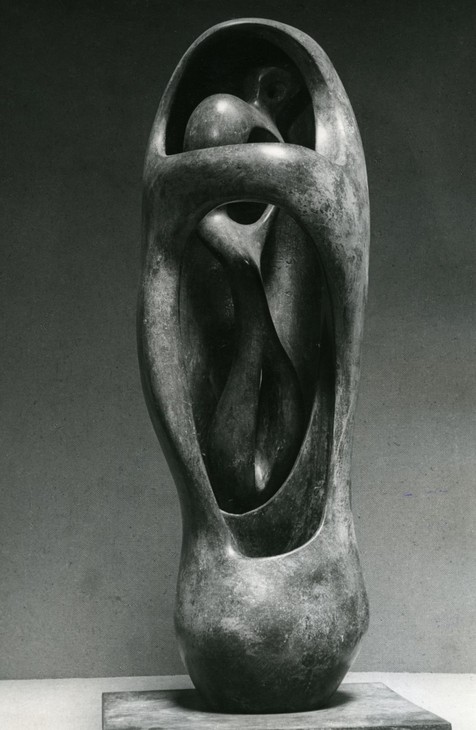

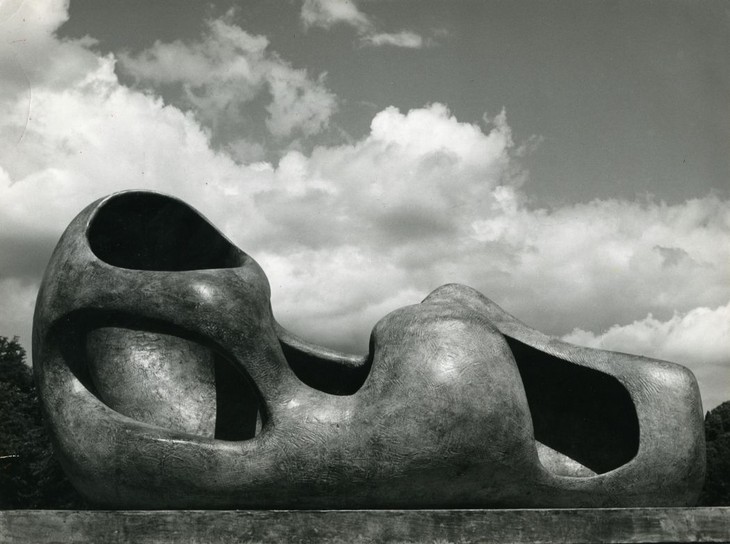

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 is a plaster sculpture comprising a vertically-orientated, rounded shell inside which an upright form is nestled. It is one of Henry Moore’s most well known sculptures and was cast in a bronze edition in c.1958.

The exterior element takes the form of an upright hollow shaft that extends from a hemispherical base to a rounded apex at the top (fig.1). While the rear is almost flat, the surface of the sides undulate and swell in places giving it an organic quality. The front, however, is marked by two large, curvaceous holes through which the interior of the form can be seen. These openings are separated by a single horizontal arch or bridge that spans the front of the sculpture approximately two thirds of the way up. Seen from the side it is evident that this bridge projects forward and overhangs the base.

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Inside this tubular casing and visible through the two openings is a thin, vertically-oriented form that is wholly contained by the walls of the exterior piece (fig.2). This internal element is made up of two rounded, roughly elliptical forms joined by a thin, cylindrical shaft which appears to twist slightly so that the rounded forms face at different angles. A wedge shape with a single hole driven through it protrudes from the top of the upper elliptical form. Its lower half curves to follow the contours of the right-hand inner wall of the sculpture, whereas its upper half bends to the curve of the left-hand edge. The way it curves to the shape of the interior wall is suggestive of a life form occupying a cocoon, with the dimensions of the inner and outer forms complementing each other in what might appear a symbiotic or organic relationship. In 1953–4 Moore created a bronze version of the internal form as a unique standing sculpture (fig.3).

Clay, plaster, elm and bronze

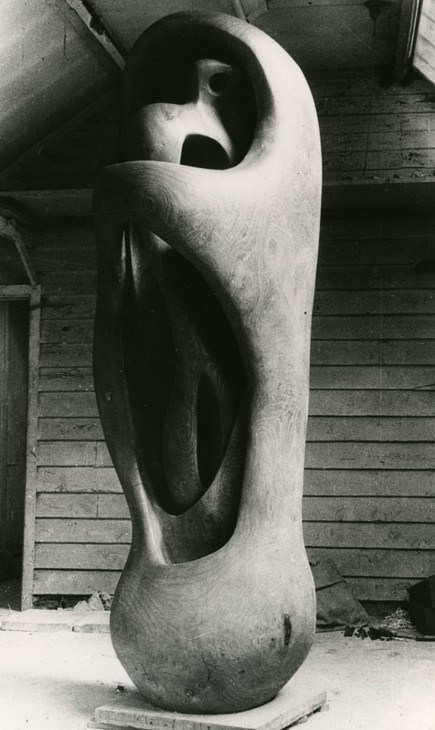

In addition to casting three bronze versions of Upright Internal/External Form Moore also carved a larger version of the sculpture in elm shortly after completing the plaster version. In October 1955 Moore wrote to Gordon Smith at the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo outlining the development of this wooden version:

The first maquette for the wood ‘Internal and External Forms’ was produced in 1951. Later the same year I made the working model (24 ½” high), which was cast into bronze. The idea was always intended to be worked out over life-size, and to be in wood. But large and sound pieces of wood are not easily found, and it was after trying unsuccessfully for a year to find a suitable piece of wood that I decided I should have to make it in plaster for bronze, and this I did (6’7” high). This was completed and about to be sent to the bronze foundry for casting when my local timber merchant informed me he had a large elm tree just come in which he thought would be exactly what I wanted. It was a magnificent tree, newly cut down, five feet in diameter at its base, and looked very sound. I bought it, and decided not to go on with the bronze version but to carry out the idea as originally intended as a wood sculpture.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Internal and External Forms 1951

Bronze

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Maquette for Internal and External Forms 1951

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Working Model for Internal and External Forms 1951

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Working Model for Internal and External Forms 1951

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

According to the art historian Kenneth Clark, the small maquette that Moore created in 1951 was made out of clay, a medium that Moore had regularly used during the 1930s and 1940s to create initial models for sculptures.2 It is probable that he worked from preparatory drawings and drew upon his existing sculptural vocabulary to create this maquette, which was later cast in bronze in an edition of seven (fig.4). Once Moore was happy with the design of the maquette it was then scaled-up to a ‘working model’ of intermediary size (fig.5). At this stage in his career the creation of a working model constituted a new development in Moore’s sculptural practice, for up until the early 1950s he had always enlarged his maquettes into full-size sculptures.3 The deployment of a working model coincided with Moore’s decision to use plaster rather than terracotta as the principal medium for his preliminary models.4 Indeed, the working model for Upright Internal/External Form and Tate’s full-scale version can be identified as among his first sculptures made in the material. Moore later reflected on the benefits of working in plaster, stating that ‘plaster is an important material for sculptors. Good quality plaster mixed with water sets to the hardness of a soft stone. I use plaster for my maquettes in preference to clay because I can both build it up and cut it down. It is easily worked, while clay hardens and dries, so that it cannot be added to’.5 During the 1920s and early 1930s Moore had been known for his advocacy of direct carving and his rejection of traditional modelling techniques, but by the 1950s he found that working in plaster afforded him greater artistic freedom to test ideas on smaller scales before committing to them. As the critic David Sylvester noted in 1955:

at an earlier stage in his career, there was no maquette, and it was a question of getting the size right in the act of making an idea real for the first time. What is more, the size had to be right first time, for the idea was generally carried out in stone or wood, which meant that mistakes could not be rectified and that the work went too slowly and the material cost too much for second attempts to be allowed.6

The working model was built over an internal wire armature and scaled up from the maquette using a mathematical system of measuring precise points on its surface. Producing a working model allowed Moore to test the design at a slightly larger size, although Sylvester observed that it was also ‘on a scale to fit the drawing room’ of any potential collector.7 In addition, the relative size of the internal and external forms could be considered in more detail. Like the maquette, the plaster working model was also cast in a bronze edition of seven.

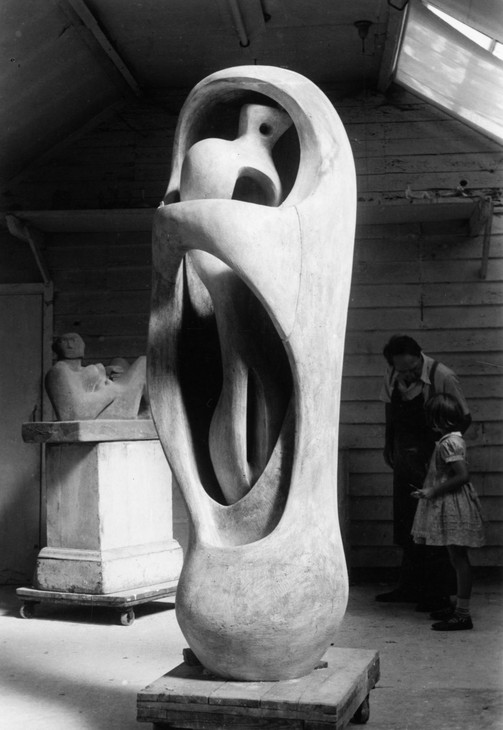

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio at Hoglands in 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio at Hoglands in 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

I have a couple of young sculptor assistants, and between the three of us we will plan the armature. You need an armature because, with plaster sculpture, you have to build on something or you’d have a great big solid piece of plaster which is unhandleable and which takes ages to build up; so one makes an armature in wood, with perhaps chicken wire roughly to shape, but enlarged to scale. My assistants can do this after they’ve been with me for a few months or so and know the sort of methods I use. To have their help saves me a great amount of time.9

Henry Moore

Internal and External Forms 1953–4

Elm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Internal and External Forms 1953–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

When Moore first started working in plaster he regarded the sculptures as stages of the creative process and not as artworks in their own right. This explains why, when discussing the elm Internal and External Forms in 1968, Moore stated that ‘there were two versions of this sculpture, one in bronze and one in wood’.14 Moore often destroyed his original plasters after all the bronzes in an edition had been cast to ensure that no additional, unauthorised casts were made. However, in the 1950s, when demand for exhibitions of his work increased, Moore began exhibiting plaster versions when bronzes – or in this case, the carved elm – were unavailable. Indeed, an additional plaster cast of Upright Internal/External Form was made by Moore’s assistants for the British Council so that the sculpture could be included in its touring exhibition of Moore’s work between 1953 and 1959.15 It is therefore likely that it was the plaster cast of Upright Internal/External Form (rather than Tate’s original plaster) that was included in the British Council’s exhibition of Moore’s work at the 1953 International Biennial of São Paulo, which later toured to Canada (1955–6), New Zealand (1956–7), South Africa (1957), Southern Rhodesia (1957), Portugal (1959) and Spain (1959). A close-up detail of the sculpture was reproduced on the front cover of the exhibition pamphlet produced to accompany the Canadian and New Zealand exhibitions. However, in his review of the New Zealand edition of Moore’s exhibition the art historian Mark Stocker cited the artist’s former assistant Anthony Caro, who stated that Upright Internal/External Form was represented by the original plaster (Tate’s sculpture) in that leg of the tour.16

Moore’s attitude towards his plasters shifted over time, and he began to see them not simply as intermediary stages in the sculptural process but as unique works of art. In the early 1970s Moore declared that ‘These are not plaster casts; they are plaster originals ... they are actual works that one has done with one’s hands’.17 In 1973 Moore recounted the moment when he began to reconsider the value of his plasters:

A friend who works at the Victoria and Albert Museum came out one day just as we were breaking up some plasters and said, ‘But why do that, because sometimes the original plaster is actually nicer to look at than the final bronze’. He was right because sometimes an idea you’ve had and that you’ve made in the original material or plaster can suit it better than what the final bronze may do ... So, this led to the idea of not destroying the plasters, leaving me with a great many of them that I would not sell but wanted to find proper homes for.18

Having decided to stop destroying his plasters, Moore was then faced with the problem of what to do with them. Selling them on the open market would increase the risk of casts being made without his permission, but he did not have the required space to keep the plasters indefinitely. A solution was found by way of philanthropic gifts, first to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto in 1974, and then to the Tate in 1978.

Henry Moore

Detail of Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 showing surface colour

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Detail of Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 showing surface colour

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Themes and origins

In 1955 Moore explained the idea behind the sculpture as ‘a sort of embryo being protected by an outer form, a mother and child idea, or the stamen in a flower, that is, something young and growing being protected by an outer shell’.21 Discussing Upright Internal/External Form in 1968 he drew further parallels, stating that,

I have done other sculptures based on this idea of one form being protected by another. These are some of the helmets I did in 1939 in which the interior of the helmet is really a figure and the outside casing of it is like the armour by which it might be protected in battle. I suppose in my mind was also the Mother and Child idea and of birth and the child in embryo. All these things are connected in this interior and exterior idea.22

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Lead

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

As Moore’s statement acknowledges, he had been thinking about the relationship between internal and external forms for some years prior to the development of his initial maquette for Upright Internal/External Form. His first sculpture exploring this theme had been The Helmet 1939–40 (fig.9). This lead sculpture was one of the last works made by Moore before the Second World War put a halt to his sculptural production in 1940.23 In it a vertical form made up of arches and ellipses, evocative of a standing figure, is enclosed within a domed shelter. When discussing his ‘Helmet Head’ series in 1980, Moore recalled that ‘the idea of one form inside another form may owe some of its incipient beginnings to my interest at one stage when I discovered armour. I spent many hours in the Wallace Collection, in London, looking at armour’.24 Given the time at which it was made, coupled with Moore’s declared interest in armoury, The Helmet and the subsequent series of helmet head sculptures may well have been prompted by the Second World War, although as Moore himself suggested, the sculptures also relate to other interests. The German psychologist Erich Neumann, for example, emphasised in 1959 that The Helmet is ‘dominated by the mother-child symbolism: it forms a uterine shell within which there dwells a child inhabitant’.25

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

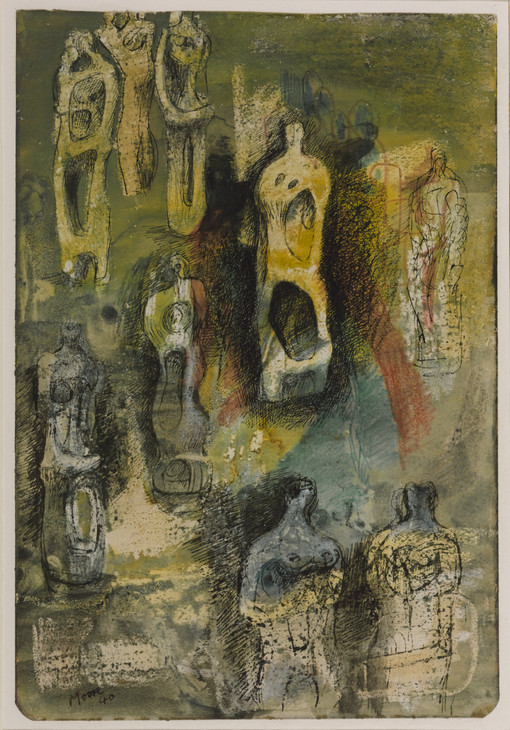

Standing Figures 1940

Wax, coloured pencil, graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

support: 264 x 181 mm; frame: 490 x 400 x 17 mm

Tate N05210

Purchased 1940

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore OM, CH

Standing Figures 1940

Tate N05210

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

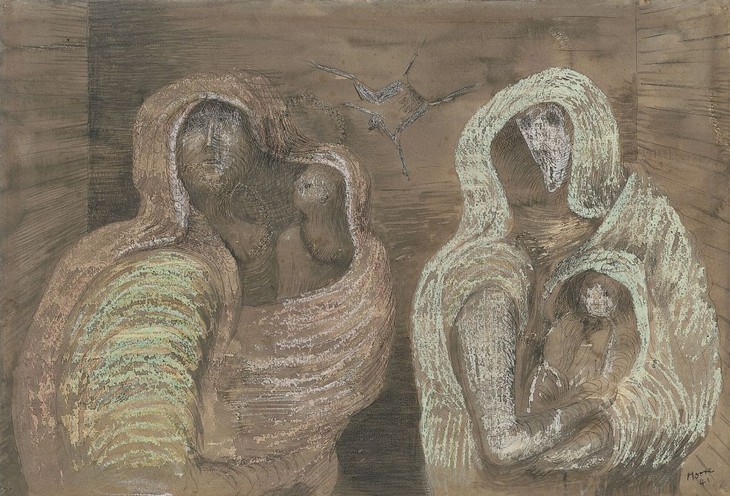

Henry Moore

Two Mothers Holding Children 1941

Pen, ink, wax crayon and watercolour on paper

380 x 564 mm

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Two Mothers Holding Children 1941

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

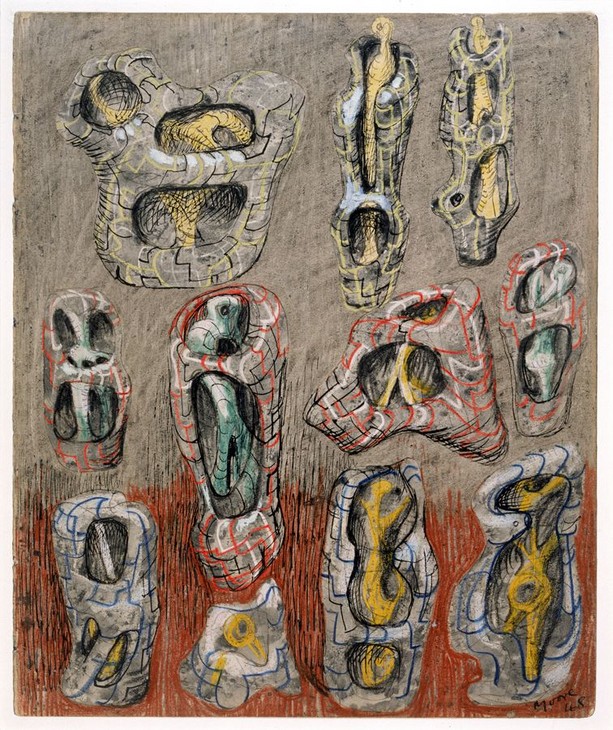

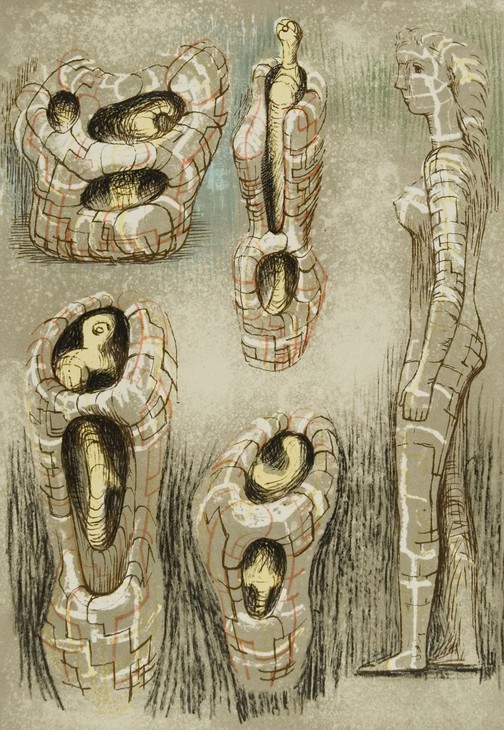

Moore resumed thinking about the relationship between interior and exterior forms in sculptural terms after the war. Drawings such as Ideas for Sculpture: Internal and External Forms 1948 demonstrate that Moore was developing ideas for the helmet-like objects and larger standing forms that first appeared in his pre-war drawings (fig.12). A sketch of Upright Internal/External Form can be seen in the centre-left of the page. Prominent features of this particular sketch include the depth inferred by the black interior against the green inner form, the upper sides of which have been picked out in white as if lit from above. The outer form has been rendered in fine black outlines while its volume has been enhanced through the use of repeated red contours.

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Internal and External Forms 1948

Watercolour, gouache, wax crayon, black Indian ink and grey ink on paper

292 x 241 mm

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Internal and External Forms 1948

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

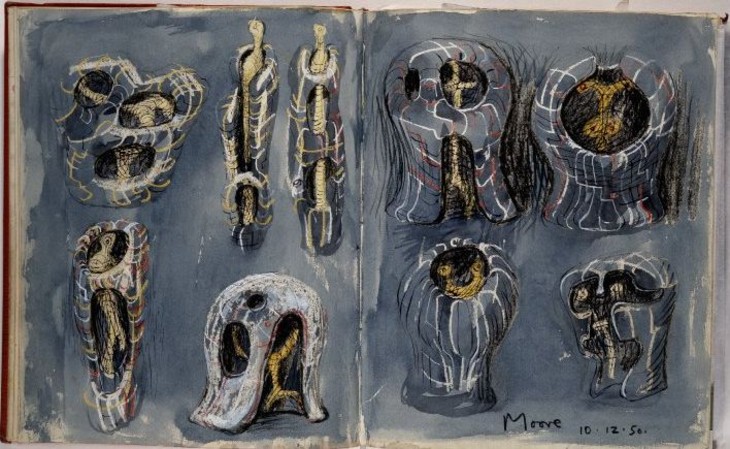

Henry Moore

Studies for Helmets and Full-Length Enclosed Figures 1950

Watercolour, pen and black ink and wax crayons over graphite on paper

251 x 402 mm

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Studies for Helmets and Full-Length Enclosed Figures 1950

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

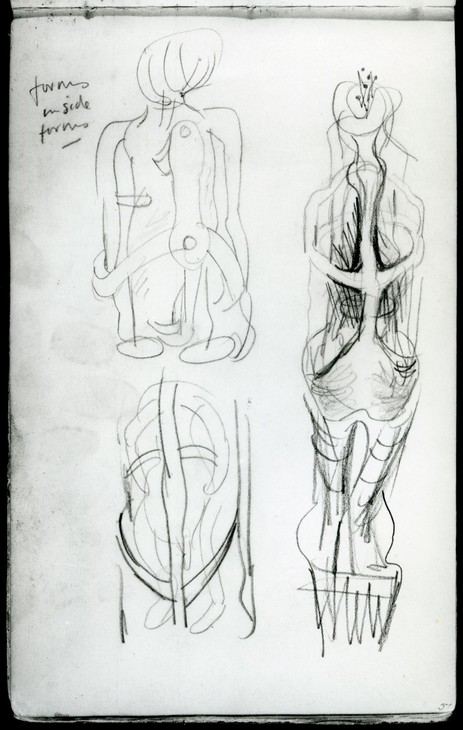

Moore’s drawings can be seen to closely track his work in three dimensions between 1948 and 1950. The year Moore created Studies for Helmets and Full-Length Enclosed Figures (fig.13) he also returned to the ‘helmet’ in sculptural form, creating Helmet Head No.1 1950 (Tate T00388). Three of the forms included in this drawing are repeated from Ideas for Sculpture: Internal and External Forms 1948, including the study for Upright Internal/External Form, visible in the bottom-left corner, the form sketched above it, and the two upright forms immediately to its right. It is likely that by the time he made this sketch Moore had clear conceptions of these forms as three-dimensional sculptures, enabling him to repeat them freely.

Henry Moore

Pandore et les statues emprisionnées 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Pandore et les statues emprisionnées 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Interpreting archetypes

Most interpretations of Upright Internal/External Form have taken as their starting point Moore’s assertion that while making this work the ‘Mother and Child idea and of birth and the child in embryo’ was at the forefront of his mind. When discussing the sculpture in 1965 and 1968 respectively, the critics Herbert Read and John Russell both cited the same extended passage from Neumann’s 1959 book The Archetypal World of Henry Moore:

What we see here, is the mother bearing the still-unborn child within her and holding the born child against her embrace. But this child is the dweller within the body, the psyche itself, for which the body, like the world, is merely the circumambient space that shelters or casts out. It is no accident that this figure reminds us of those Egyptian sarcophagi in the form of mummies, showing the mother goddess as the sheltering womb that holds and contains the dead man like a child again, as at the beginning. Mother of life, mother of death, and all-embracing body-self, the archetypal mother of man’s germinal ego consciousness – this truly great sculpture of Moore’s is all these things in one. And just for that reason it is a genuine bodying-forth of the unitary reality that exists before and beyond the division into inside and outside, a profound and final realisation of the title it bears: Internal and External Forms. Outside and inside, mother and child, body and soul, world and man – all have been made ‘real’ in a shape at once tangible and highly symbolic.29

It is worth noting that neither Russell nor Read substantially unpacked or expanded upon Neumann’s ideas. Read simply asserted that the forms of the sculpture were determined by ‘the archetypal forms of womb and foetus’.30 According to Neumann, Moore’s use of ‘archetypes’ – subjects or forms that may be recognised and understood universally – and specifically those of the ‘mother goddess’ or ‘earth mother’, was a direct response to the Second World War:

The artist’s fascination by the mother archetype is, however, by no means only a personal phenomenon of his individual history; it represents an advance into a psychic realm that is of fateful importance not only for himself but for his whole age, if not for mankind in general ... In an age when Western man, through his exaggerated respect for the patriarchal spirit and the techniques it has engendered, is in danger of losing contact with the roots of existence, there has arisen in the unconscious, in accordance with a general psychic law, a compensatory tendency that is reactivating this feminine, maternal earth-nature aspect, which has been too much repressed.31

For Neumann, Moore’s sculptures were manifestations of a universal turn to ‘Mother Earth’ as a source of restoration and sustenance in the post-war period. As such, his works could be regarded as representative of a variant of humanist philosophy that flourished during the post-war years. Industrial technology, monolithic institutions and an absolutist view of human progress had brought about unprecedented destruction during the Second World War, and among other things humanists sought to align the goals of human progress with an appreciation for nature, of which humanity itself was a part. Accordingly, a common justification for the attribution of humanist tendencies to Moore’s sculptures was his use of organic, natural forms.32 Given Moore’s reference to a ‘stamen in a flower’, the rounded surfaces of Upright Internal/External Form might be said to resonate with organic forms such as seed pods or chrysalises. Philip Hendy, director of the National Gallery, seemed to anticipate this aspect of Upright Internal/External Form when he wrote in 1949: ‘who knows what elemental emotions have stirred this rhythmic ebb and flow of form which links the tunnelled hollow with the swelling boss? Man came to life through woman, and in her loses and finds himself again’.33

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form (Flower) 1951

Bronze

Didrichsen Art Museum, Helsinki

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form (Flower) 1951

Didrichsen Art Museum, Helsinki

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

that Moore first carved this idea in wood is one of those chances that is not an accident, because the internal-external forms, in addition to their biological and psychological implications, are examples of his responsiveness to nature. The apertures and caves of a hollow tree, however familiar they may become, never quite lose the mystery that they held for us in our childhood.35

Malangan figure from New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, c.1882–3

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.16

Malangan figure from New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, c.1882–3

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

New Ireland carvings like this made a tremendous impression on me through their use of forms within a form. I realised what a sense of mystery could be achieved by having the inside partly hidden so that you have to move round the sculpture to understand it. I was also staggered by the craftsmanship needed to make these interior carvings. The so-called primitive peoples were often just as advanced in technique as the more developed societies.37

Moore’s knowledge of ‘so-called primitive’ cultures first came from reading the art critic Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920) while studying at Leeds School of Art in 1920. Fry’s book contained chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American art and exemplified the increasingly widespread belief that non-Western or ancient art was more expressive or authentic than the academic classicism of European fine art traditions. As the art historian Christopher Green has suggested, for Fry and many others the turn to primitive art ‘offered a stimulus for rebuilding the broader terms of the European tradition’.38 Moore later recalled that ‘Fry opened the way to other books and to the realisation of the British Museum. That was the beginning really’.39

Henry Moore

Internal/External Forms c.1935

Graphite on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Internal/External Forms c.1935

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Originating from a sketchbook dated 1935 on its front cover (known as Sketchbook B), the drawing Internal/External Forms, according to Wilkinson, ‘was almost certainly the first of the internal/external drawings executed between 1935 and 1940’.43 However, Ann Garrould, the cataloguer of Moore’s drawings, has suggested that it is unlikely that all of the drawings contained within Sketchbook B date from 1935. She has proposed that, given the range of styles, media and subjects featured in the sketchbook, some of the drawings may date to the early 1930s, while others may have been executed at ‘the end of the 1940s when he was jotting down ideas for Prométhée’.44 Whether or not it was executed in the 1930s or 1940s, the drawing is a useful indicator of Moore’s early development of the figurative element of Upright Internal/External Form.

Critical reception

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure (Internal and External Forms) 1951

Bronze

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure (Internal and External Forms) 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

these are powerful and dramatic works, disturbing to contemplate because of the insistence with which they invite us to project ourselves in imagination into their uterine cavities. The fact that their scale makes this physically possible is indispensible to this effect, for it does not operate at all in the small version of these two sculptures, which Moore made about three years ago and which without it seem quite pointless. Nothing could show more convincingly the truth of a statement which Moore made in 1937: ‘There is a right physical size for every idea’ ... The smaller and larger versions of these exterior-interior sculptures are almost indistinguishable in shape, yet the difference in their size makes for all the difference between meaningless formal invention and plastic poetry.45

The elm version of Upright Internal/External Form (titled Internal and External Forms) was included in Moore’s solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, London, in 1955. In his review of this exhibition Sylvester elaborated upon the issues of size and scale, asserting that the sculptural form of Upright Internal/External Form was ‘incomparably more successful’ in its enlarged state.46 However, Sylvester reflected that ‘if there is a criticism to be made’ of Upright Internal/External Form and its reclining counterpart (also included in the exhibition), ‘it is that they are really only an elaboration of formal ideas which Moore first explored in the late nineteen-thirties and that, while they are bigger than the things of their kind he attempted then, they are better only in terms of technical accomplishment’.47 He suggested that the large-scale elm sculpture lacked the ‘kick’ or immediacy of some of his earlier works, concluding that ‘it is not easy for any artist, least of all an artist of Moore’s wide-ranging mind to sustain over a period of twenty years the imaginative impetus and intensity that an idea is charged with when it is first conceived’.48

The art historian Alan Bowness was more effusive in his review of the Leicester Galleries exhibition, writing that:

the magnificent Upright Exterior and Interior Forms ... is in the traditional Moore manner, organic humanist sculpture, in which the forms have that elemental power Moore so admired in primitive art ... From a superb piece of elm-wood, the exterior form is hollowed out to cradle the interior form, which seems to be twisting and shouldering its way out of an enclosing womb.49

‘Elemental’ was a term used more than once to describe the elm version. An unnamed critic writing in the Times stated:

Mr Henry Moore’s exhibition of recent sculptures and early drawings at the Leicester Galleries is dominated by two massively characteristic works – a stylised structure in elm wood entitled ‘Upright Exterior and Interior Forms’ and a large wholly formal ‘Reclining Figure’ in bronze with a green patina. The light sheen of the wood, the smoothness and poise with which the whole tension of hollow spaces and curving forms has been carved out of what was originally one vast tree trunk make this first exhibit arresting work. (It has, incidentally, already been purchased by an American museum.) The relation between the strongly carved outer shell with its round solid base and the lithe interior forms have something elemental about it (an emotionally disturbing quality that contrasts with the more placid rhythms of the reclining bronze) – familiar in form – in which the spaces and forms are harmoniously and integrally reconciled.50

The American museum that had acquired the elm version was the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo. In 1955 Moore wrote to the curator Gordon Smith regarding the display of the sculpture, explaining that he preferred for it to be shown in top-lit gallery spaces so that light ‘does not shine too directly into the interior’. Moore found that lighting the sculpture from above ‘lets the interior look like a cave, with some mystery in it’.51 He went on to state:

I think its height need not be more than a few inches above the ground as already it looks large enough, and raising it would make it perhaps too cut off from the spectator. Its idea needs to be connected with the size of a human being and the spectator should be able to imagine himself standing in the place of the interior form.52

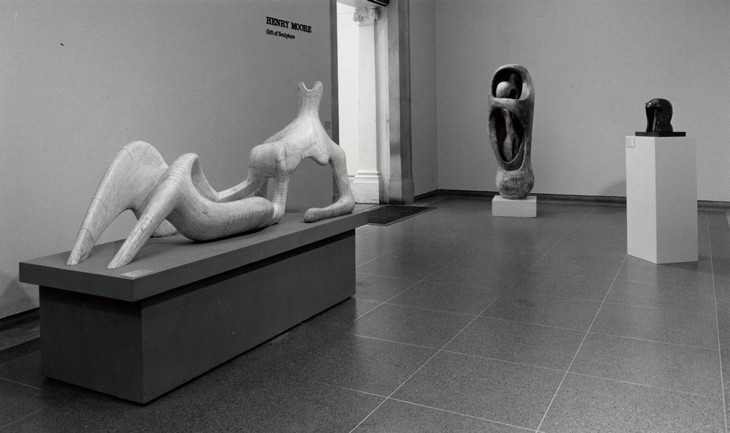

In 1960 one of the bronze casts of Upright Internal/External Form was exhibited in Moore’s solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. Curated by Bryan Robertson, the show comprised sculptures made since 1950 and was Moore’s first major exhibition in London since his 1955 show at the Leicester Galleries. In 1968 Moore reflected that:

The good thing about my exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery, which Bryan Robertson arranged and organised so well, was that, for the first time, I had thirty or more sculptures all in one room, rather than in several smaller rooms. I liked the fact that the Gallery is on ground level and opens straight onto the street, so that people are encouraged to come in. Women even brought their children in prams. That doesn’t happen in many galleries.53

The exhibition was generally well received in the press. The critic Keith Sutton wrote in the Listener that ‘the power and quality of it all is undeniable and satisfying’,54 while the critic David Thompson declaring in the Times that:

the quite extraordinary power and authority of the finest pieces in the exhibition exist in a sort of loneliness and silence, withdrawn from the madding crowd. This in itself is one of the many paradoxes inherent in the appeal of Moore’s art. As often as it retreats from immediate human contact and sympathy, it solicits them by its strong sense of pathos.55

However, in 1994 Bryan Robertson revealed that some visitors to the 1960 exhibition had felt uneasy about Moore’s work. Considering the exhibition in relation to the Whitechapel’s 1954 display of sculptures by Barbara Hepworth, Robertson recalled that he ‘discovered that the public was more at ease at that time with total abstraction, provided it was free of any morbidity, than awkward semi-abstract work with worrying figurative undertones. Moore’s sculpture, shown later at Whitechapel, was more of a problem for the uninitiated’.56

The Henry Moore Gift

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery 1978

Tate Archives

Fig.19

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 on display in the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery 1978

Tate Archives

Alice Correia

January 2014

Notes

Henry Moore, letter to Gordon Smith, 31 October 1955, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.277.

See, for example, Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1 (Tate N06004), which was developed from the maquette to full size without a working model.

David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007, p.11.

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore. From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.226.

Margaret McLeod, letter to Richard Calvocoressi, 18 August 1980, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23946

Mark Stocker, ‘The Best Thing Ever Seen in New Zealand: The Henry Moore Exhibition of 1956–57’, Sculpture Journal, vol.16, no.1, 2007, p.89, note 35.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.18.

Anita Feldman, ‘Moore: The Plasters’, in Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, pp.12, 19.

Henry Moore in conversation with David Mitchinson, 1980, extract of transcript reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.213.

Neumann 1959, pp.127–8, cited in Read 1965, pp.185–6 and John Russell, Henry Moore, New York 1968, p.121.

For a discussion of Moore and humanism see James Hyman, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain during the Cold War 1945–1960, New Haven and London 2001, pp.90–5.

In his introduction to the book Moore concluded that ‘It has been a wonderful experience for me to recapture the delight, the excitement, the inspiration I got in these pieces as a young and developing sculptor’. Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.16.

Christopher Green, ‘Expanding the Canon: Roger Fry’s Evaluations of the “Civilized” and the “Savage”’, in Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London 1999, p.126.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

Henry Moore, ‘Primitive Art’, Listener, 24 April 1941, pp.598–9, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.105.

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’ in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth Century Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, vol.2, p.605.

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Moore: A Modernist Primitive’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.38.

Our Art Critic [David Thompson], ‘Mr Henry Moore’s Exhilarating Exhibition’, Times, 28 November 1960, p.6.

These figures are based on those listed in a memo in the records for the exhibition. See Tate Public Records TG 92/344/2.

Andrew Gagarin was identified as the owner of one of the bronze casts in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, p.xxvi. See also ‘Henry Moore, Internal and External Forms, 1958, Lot 66’, Impressionist & Modern Paintings, Drawings & Sculpture. Part 1: Sale 8410, sales catalogue, 30 April 1996, Christie’s, New York 1996, http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/LotDetailsPrintable.aspx?intObjectID=1073086 , accessed 7 January 2014.

Related essays

- ‘A stimulation to greater effort of living’: The Importance of Henry Moore’s ‘credible compromise’ to Herbert Read’s Aesthetics and Politics Ben Cranfield

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Life Forms: Henry Moore, Morphology and Biologism in the Interwar Years Edward Juler

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

Related reviews and articles

- Philip Hendy, ‘Henry Moore: his New Exhibition’ Britain Today, no.158, June 1949.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www