Henry Moore OM, CH Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Image 1 of 16

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

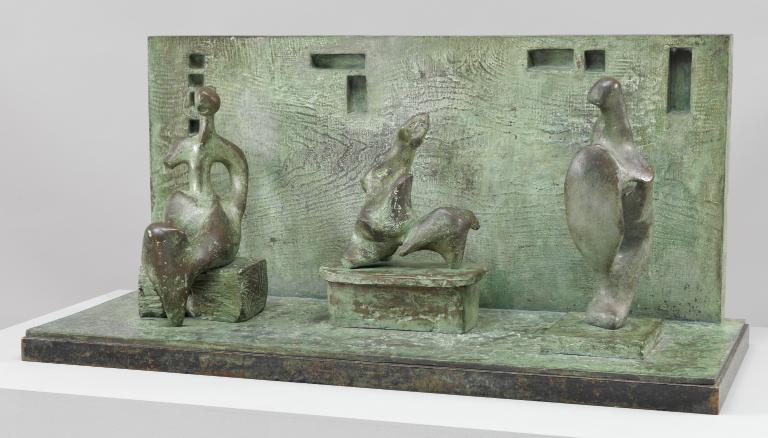

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Three Motives Against a Wall No.1

1958, cast 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

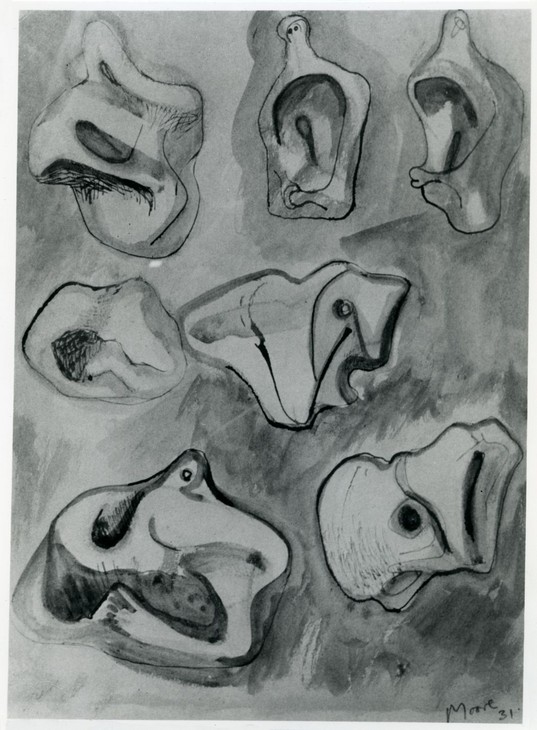

The subject of this sculpture recalls aspects of Moore’s work of the 1930s, in particular his drawings of enclosed spaces.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Three Motives Against a Wall No.1

1958, cast 1959

Bronze

505 x 1080 x 440 mm

Purchased from the artist by the Victoria and Albert Museum 1961; transferred to the Tate Gallery 1983

Number 6 in an edition of 12 plus 1 artist’s copy

T03763

Three Motives Against a Wall No.1

1958, cast 1959

Bronze

505 x 1080 x 440 mm

Purchased from the artist by the Victoria and Albert Museum 1961; transferred to the Tate Gallery 1983

Number 6 in an edition of 12 plus 1 artist’s copy

T03763

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist by the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1961; transferred to the Tate Gallery, 1983.

Exhibition history

1962

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Arts Council Gallery, Cambridge, February–March 1962 (?another cast exhibited no.41).

1964

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore at King’s Lynn, St Margaret’s Church, King’s Lynn, July–August 1964 (?another cast exhibited no.31).

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone, April–May 1966 (?another cast exhibited no.25).

1969

Henry Moore, Heslington Hall, York, March 1969 (?another cast exhibited no.21).

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, August–October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975 (?another cast exhibited no.56).

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976 (?another cast exhibited no.59).

References

1959

Nineteenth and Twentieth Century European Masters, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1959 (another cast reproduced no.92).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960 (another cast reproduced p.189).

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960 (another cast reproduced no.60).

1961

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Musée Rodin, Paris 1961 (another cast reproduced pl.34).

1962

Henry Moore: Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawing, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1962 (another cast reproduced pl.15).

1965

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Galleria d’Arte, Rome 1965 (another cast reproduced no.6).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.219 (another cast reproduced pl.203).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.53–5.

1968

Ionel Jianou, Henry Moore, Paris 1968 (another cast reproduced pl.69).

1972

Giulio Carlo Argan, Henry Moore, New York 1972 (another cast reproduced p.155).

1972

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972 (another cast reproduced p.172).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973 (another cast reproduced pl.103).

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973 (another cast reproduced p.182).

1981

David Mitchinson and Franco Russoli, Henry Moore: Sculpture, London 1981, p.151 (another cast reproduced pl.325).

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983 (another cast reproduced p.82).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.441 (another cast reproduced pl.75).

1986

Henry Moore: Model to Monument, exhibition catalogue, Kent Fine Art, New York 1986 (another cast reproduced p.12).

1988

[Judith Collins], ‘T.03763 Three Motives Against a Wall No.1’, The Tate Gallery 1984–86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982–84, London 1988, pp.541–2, reproduced p.541.

1995

Henry Moore: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, BWA Gallery, Krakow 1995 (another cast reproduced no.85).

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998 (another cast reproduced p.205).

2001

Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001 (another cast reproduced pl.73).

2005

David Mitchinson (ed.), Henry Moore and the Challenge of Architecture, Much Hadam 2005, p.27.

2006

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Three Motives against Wall No.1’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London, 2006, pp.256–58 (another cast reproduced pl.185).

Technique and condition

Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958 is a bronze sculpture consisting of three biomorphic forms each positioned on individual bases, which are all fixed with screws to a larger rectangular bronze base. Another bronze rectangle is attached at a perpendicular angle to the base and provides a backdrop to the three forms. The sculpture is coloured a vivid bright green with dark brown highlights and it rests on a plywood mount clad with copper sheet.

Moore originally made each of the elements of this sculpture in plaster and perhaps spent time positioning the biomorphic forms in different configurations before settling on the final arrangement. Moulds would then have been taken of each element and used to cast them in bronze. This sculpture was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London in an edition of twelve plus one artists copy.

Detail of casting investment on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of casting investment on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of rear wall of Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of rear wall of Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The presence of investment in some crevices suggests that the three biomorphic forms and their individual bases were cast using the lost wax technique (fig.1), whereas the base and backdrop are more likely to have been sand cast, as is revealed by the slightly granular texture to the surface at the back (fig.2).1 It is likely that these two flat pieces are welded at the point where they meet. Looking closely at this sculpture it is possible to see how Moore carefully textured the surfaces. On the figures there are many thin striations made using a combination of fine saw blades, and fine lines that would have been incised into the original plaster model (fig.3). To create the raised wood grain texture on the backdrop it is likely that Moore simply pressed a wooden surface against a soft clay slab. The same method was probably used to create the deeply impressed square and rectangular marks in the same surface. Close examination reveals that there are also numerous stippled linear and dotted impressions on the vertical face and top edge of the backdrop, some of which may have been applied after casting by using small metal punch tools. The bronze base has an undulating surface where the high points have been abraded flat.

Detail of incised lines on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of incised lines on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of patina on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of patina on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After casting the bronze was coloured by means of a process called artificial patination. This process involved applying chemical solutions that reacted with the bronze to produce various coloured compounds. The colour of this sculpture was achieved by first applying a dark brown layer using a chemical such as potassium polysulphide (often known as ‘liver of sulphur) and then a green patinating solution over the top. There are many different patina recipes used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts dissolved in water. The solution is usually applied in successive layers until the desired colour is achieved. The patinator lightly abraded the green patina on high points of the form to reveal the underlying brown colour before applying a clear wax to consolidate and protect the finished patina (fig.4). A patina has also been applied to the copper sheet on the mount which has resulted in a stippled green and black effect.

There is no artist’s inscription or foundry mark visible on this sculpture.

Lyndsey Morgan

November 2012

For a film explaining the lost wax casting method see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/videos/l/lost-wax-bronze-casting/ , accessed 18 February 2014. Sand casting is a technique whereby a model is buried in sand to create a mould from which the bronze can be cast. Sand casting is quicker and less labour intensive than lost wax casting but generally less suitable for reproducing very intricate shapes or surface details.

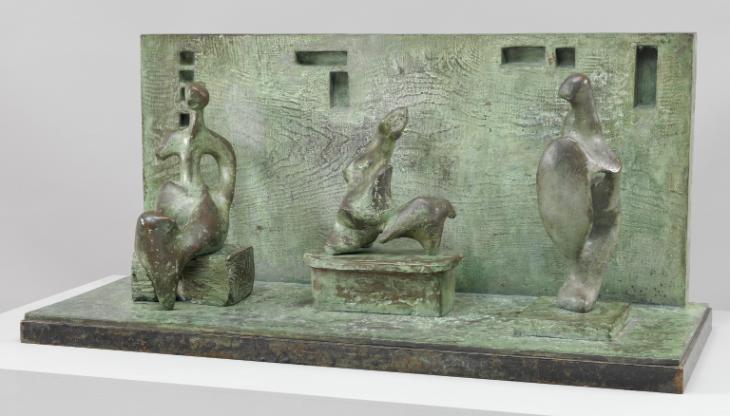

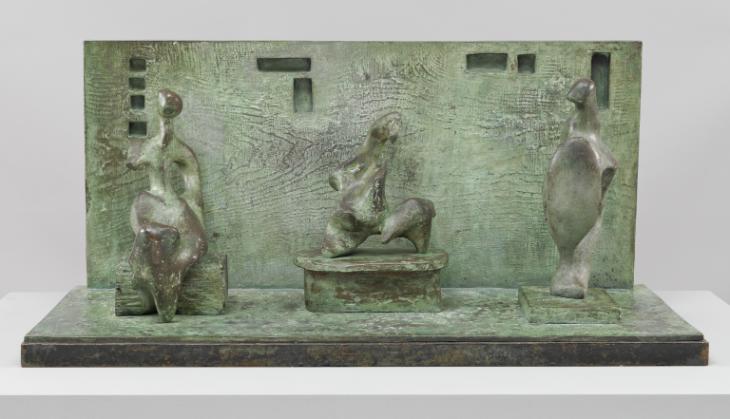

Entry

Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 comprises three individual amorphous forms positioned in a row on a stage-like platform set against an upright rectangular wall. The platform and rear wall are joined together to create a right-angled unit, which is mounted onto a copper-covered wooden base. The wall is textured with a wood-grain effect and is imprinted with an arrangement of square and rectangular depressions. Although none of the three forms or motives depicts a realistic human figure, each one is reminiscent of a human body and has an identifiable head supported by a torso. They are positioned on individual plinths of differing shapes and sizes and can be identified from left to right as a seated figure, a reclining figure and a standing figure.

The seated figure on the left (fig.1) has a bulbous head and a long neck. A ridge runs down the length of the long tubular body from the neck to the waist while two curved shoulders lead down to arms. The right arm has been cut just below the shoulder, leaving just a stump, but the left arm extends backwards before curving down and around to the waist. The hips are wide and the buttocks sit on a textured cuboid plinth. Individual legs have not been distinguished, although a depression has been made in the figure’s lap that accentuates the rise of the right knee and gives the impression that the left knee is tucked underneath the right. The lower half of the figure thins to a single conical point at its base. Overall the curve of the body and legs gives the impression that the figure is leaning backwards and slouching.

The central motive (fig.2) is the least naturalistic of the three figures and may be understood as a reclining figure in that the whole body is angled on a table-like plinth. Made up of sweeping forms, the body consists of a roughly modelled head attached to a long thrusting neck and shoulders that merge into an undulating protrusion that pushes out from the torso and might represent breasts. There are no discernable arms and the single form that takes the place of the legs arches upwards before thinning and curving back down towards the plinth. From the raised knee two spurs project outwards like fronds. Beneath this curved knee is an arched space through which the rear wall can be seen.

The motive on the right (fig.3) is positioned on a shallow square plinth and features a smooth oval shape on its front that loosely resembles a shield. Seen from the side, the body is angled so that the short legs extend backwards towards the rear wall while the torso and head lean towards the front. The figure stands on a single triangular foot and its leg takes the form of a prism. Behind the shield-like front is a network of holes and hollows that separate the torso and legs into curved, tubular, interconnected forms. The head is turned over the right shoulder as though the figure is looking towards its counterparts and is incised with two widely spaced nostrils. This is the tallest of the three motives and appears to represent a standing figure.

Detail of central motive in Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of central motive in Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of right motive in Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of right motive in Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although the three motives are evenly spaced on the base and positioned in a single row, when seen from the side they appear to fan out from the rear of the platform to the front: the left motive leans backwards, the middle motive is upright and the right motive leans forward, creating a sense of movement that encourages a consideration of the relationships between each of the elements.

Unlike the rear wall, with its wood-grain texture and square and rectangular indentations, the three motives have generally smooth surfaces, especially the standing figure on the right. However, crevices and pock marks can be seen on the middle motive, which has also been incised with a series of individually incised parallel lines.

From plaster to bronze

In order to make the motives in bronze Moore would have first made each element in plaster (fig.4), building up the form in layers until it could be modelled and shaped using spatulas and metal modelling tools. It is likely that Moore carved hollows through the plaster in order to create the forms of the standing motive (fig.5). It is not known exactly how Moore made the rear wall in bronze, but according to former Tate curator Judith Collins he either cast a plaster version that had been imprinted with a piece of wood and into which he carved out the rectangular and square recesses, or he ‘cut the recesses into a plank of wood and then had this cast into bronze without a plaster intermediate stage’.1

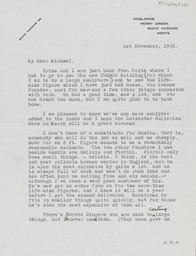

Henry Moore

Maquette of left motive for Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Maquette of left motive for Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Maquette of right motive for Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Maquette of right motive for Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is probable that Moore made the plaster motives in his small maquette studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. The studio was lined with shelves on which his collection of bones, shells, and pebbles – what he called his ‘library of natural forms’ – was stored.2 It is known that Moore often borrowed shapes from these organic objects when making his sculptures and it is probable that the curvilinear forms of the motives originated from his study of bones and stones. When they were completed Moore sent the plaster maquettes to a professional foundry to be cast. The log book in which Moore recorded when and where an edition was cast reveals that Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London, run by Charles Gaskin. It is likely that Moore first came into contact with the foundry when he was Head of the Sculpture Department at Chelsea College of Art in the 1930s because it was located close to the college and was used regularly by staff and students. The sculpture exists in an edition of twelve bronzes plus one artist’s copy, and which were cast between March 1959 and July 1960. Tate’s copy, which was number six in the edition, was made in August 1959.3

At the foundry the technicians would have used the original plaster motives to create hollow moulds into which molten bronze could be poured, and from which multiple bronze versions could be made. Investment in the crevices of the middle motive suggests that it (and the other motives) were probably cast using the lost wax method (fig.6). The base and the backdrop were probably cast using the sand casting method because the grainy texture on the back of the rear wall is typical of this casting method (fig.7).

Detail of casting investment on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of casting investment on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of rear wall of Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Detail of rear wall of Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of patina on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of patina on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Origins and development

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Travertine marble

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Unesco Reclining Figure 1957–8

Unesco, Paris

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In the case of the UNESCO commission he had to invent both concept and image, some symbol that had relevance to the educational and scientific aims of the institution established by the United Nations. There are several illustrations in this volume which show the artist struggling with the problem ... Some of these [preparatory] maquettes ... also illustrate the subsidiary but still very harassing problem of having to accommodate the piece of sculpture against a background of busy fenestration which tended to destroy its outlines and mass. The sculptor played with the possibility of interposing his own wall between the figure and the building, and though this solution was abandoned, it led to a theme, ‘the wall’, which the sculptor was to exploit later.8

Henry Moore

Maquette for Seated Figure against Curved Wall 1955

Bronze

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Maquette for Seated Figure against Curved Wall 1955

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s decision to imprint wood grain on the upright wall of Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 may be linked to the automatist techniques of frottage and grattage exemplified by surrealist works such as Max Ernst’s Forest and Dove 1927 (Tate T00548). Frottage is the French word for rubbing and refers to the way textured surfaces are transcribed by laying sheets of paper on top of an object, which are then rubbed over with a soft pencil. Grattage, by contrast, involves scraping off layers of paint to reveal textures below. For Ernst, these techniques provided a way of incorporating chance procedures in the making of a work that yielded unexpected forms and compositions, and it may be that Moore utilised a similar technique to create the wood-grain effect, albeit in a conscious, controlled way.

During the 1930s Moore was closely linked with surrealism: his friends Herbert Read and the artist Roland Penrose were at the centre of the surrealist movement in England, and he exhibited in a number of surrealist exhibitions in London during the decade. Furthermore, according to the critic Robert Melville, although Moore ‘took no part in the doctrinal discussions’ of the surrealists, ‘during the period from 1931 to the beginning of the war, Moore carved a superb series of organic abstractions’ that he argued ‘reveal his connections with Surrealism. He belongs to the Surrealist generation’.12 Four Forms 1936 (fig.11), for example, comprises four individual amorphous organic and geometric constructed components arranged in a row on a rectangular base. The arrangement of strange and seemingly unrelated abstract forms in a row also became the subject of a series drawings made around the same time that, importantly, also feature background walls marked by rectangular recesses, and thus relate closely to Three Motives Against a Wall No.1.

Henry Moore

Four Forms 1936

Stone

Indiana University Art Museum

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Four Forms 1936

Indiana University Art Museum

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

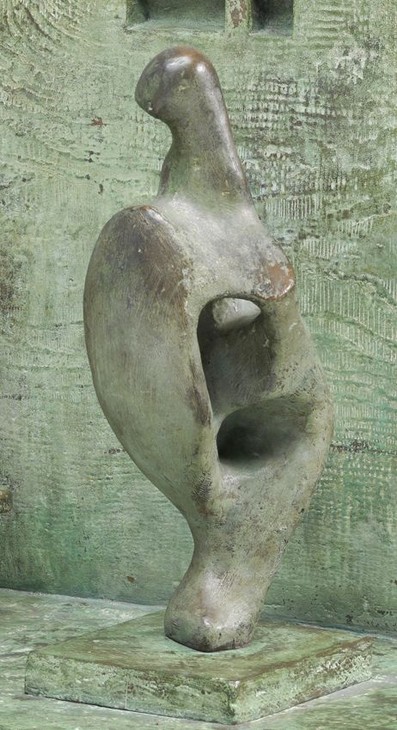

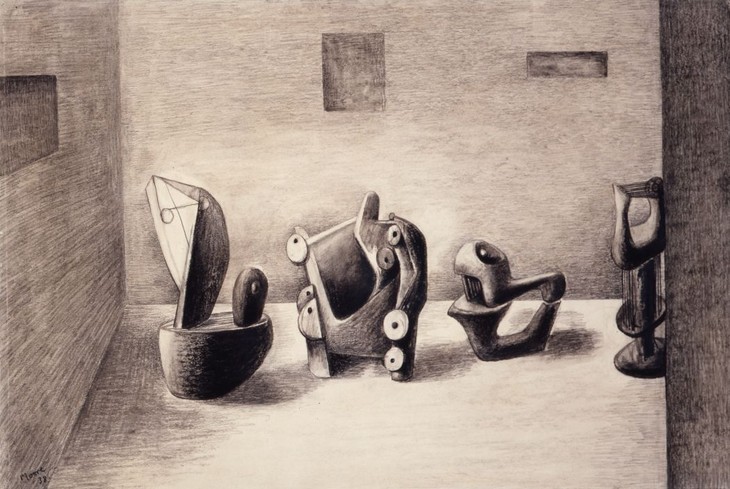

the placing of the Ideas for Sculpture [fig.13] in a ‘setting’ animates these mysterious beings to an extraordinary degree and makes them even more uncanny. The setting ... [may] be taken as a symbol of our civilisation, or our urban, walled-in existence, and of the restrictedness of our consciousness, which has lost touch with nature and life. It is a prison life that the setting shows us, and our estrangement from nature, our imprisonment in a world of walls, is revealed in the eerie loneliness that surrounds each of the figures trapped in this terrifying milieu.14

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

Charcoal, chalk and ink wash on paper

381 x 557 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

Chalk, wash, pen and ink on paper

381 x 559 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting 1938

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Neumann went on to discuss Moore’s uncanny architectural spaces in relation to the work of the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), whose work was admired by surrealist artists including René Magritte and Paul Nash. De Chirico’s paintings frequently depict enigmatic town squares, shadowy architectural facades and claustrophobic urban environments that create a tense and menacing atmosphere.

Henry Moore

Seven Ideas for Sculpture 1931

Pen and ink, wash, watercolour on paper

372 x 273 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Seven Ideas for Sculpture 1931

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

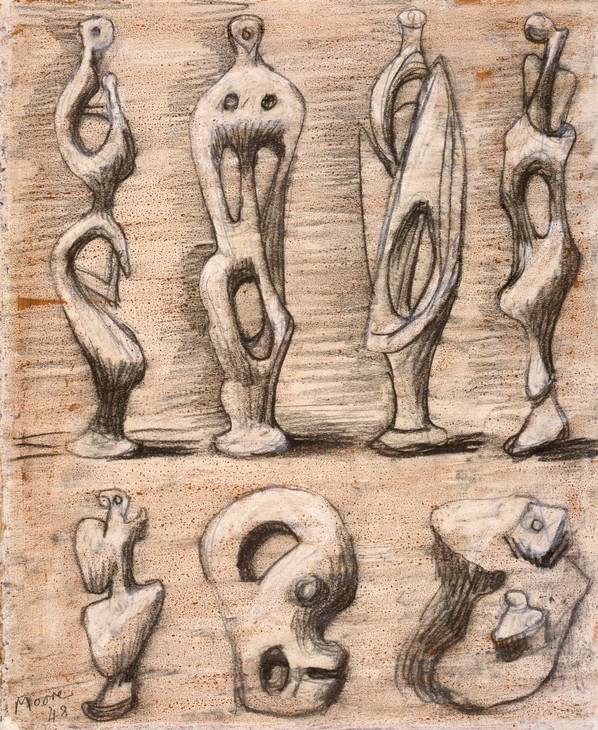

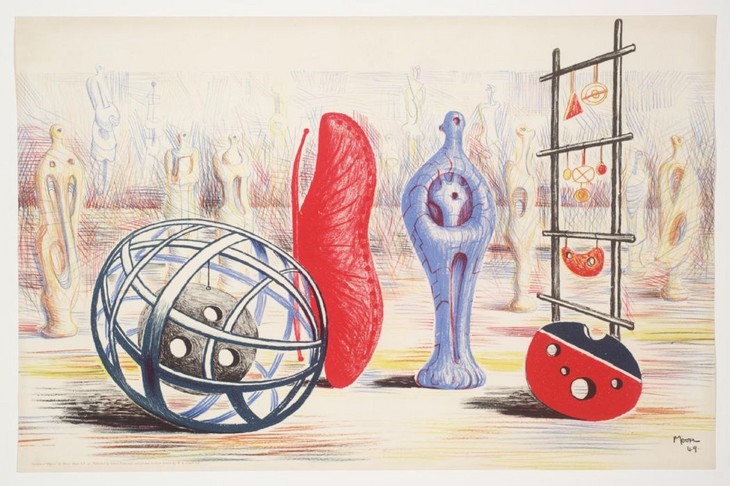

During the 1940s Moore’s sculptural production came to a near-standstill due to a lack of available materials brought about by the Second World War. Instead, Moore produced numerous drawings, recording his ideas for sculpture. Standing Figures and Ideas for Sculptures 1948 (fig.15) presents an arrangement of seven designs for sculptures, including in the upper right, a sketch for a standing figure that anticipates the right-hand motive of Three Motives Against a Wall No.1. This one-legged figure, which appears to hold a pierced shield in front of its torso, reappears in a lithographic print of 1949 titled Sculptural Objects (fig.16), which presents an array of standing forms alongside a cage-like sphere and a self-supporting ladder, set within an undefined landscape. The standing figure in the middle distance on the far right of the print has a striking resemblance to the sculptural motive on the right of the sculpture, with an elliptical shield protecting a hollowed torso, standing upright on a single leg.

Henry Moore

Standing Figures and Ideas for Sculptures 1948

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash on paper

254 x 432 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Standing Figures and Ideas for Sculptures 1948

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Sculptural Objects 1949

Lithograph on paper

495 x 762 mm

Tate P01714

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Sculptural Objects 1949

Tate P01714

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

By the time Moore created Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 in 1958 he rarely, if ever, produced preparatory sketches for sculptures, preferring instead to make small hand-held, three-dimensional models in a malleable material such as clay, plaster or wax. When asked in 1960 how he arrived at an idea for sculpture, Moore replied:

Well, in various ways. One doesn’t know really how ideas will come. But I can induce them by starting with looking at a box of pebbles. I have collected bits of pebbles, bits of bone, found objects, and so on, all of which help to give an atmosphere to start working. Then with those pebbles ... I sit down and something begins. Then perhaps at a certain stage the idea crystallizes and then you know what to do, what to alter.16

A particular flint stone in Moore’s collection – known from photographs taken when it was exhibited at Marlborough Fine Art, London, in 1971 (fig.17) – may have inspired the form of the middle motive in Three Motives Against a Wall No.1, to which Moore added a horizontal section denoting legs, thus transforming the stone into a semi-figurative object. In 1959 this motive was cast as a distinct sculpture and given the title Animal Form (fig.18). In his book examining Moore’s depiction of animals the writer W.J. Strachan placed Animal Form alongside other works inspired by bones and noted that bones are ‘always an underlying element in Moore’s sculpture’.17 The transformation of these shapes into evocations of human figures and animal forms imbue them with an uncanny quality, in that they seem familiar and yet not of this world. Despite their strangeness, however, Neumann argued that ‘they are certainly no more improbable than an elephant would be for a man who had never seen one, and the fact that they deviate from the human shape in certain particulars but resemble it in others is a feature they have in common with a number of other creatures that actually exist’.18

Flint stone from Henry Moore's collection on display at Marlbrough Gallery, London, June 1971

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Flint stone from Henry Moore's collection on display at Marlbrough Gallery, London, June 1971

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Animal Form 1959

Bronze

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Animal Form 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1963–5

Bronze

Lincoln Center, New York City

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1963–5

Lincoln Center, New York City

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Ownership history

In a letter to Moore dated 9 August 1960, Carol Hogben, Assistant Keeper in the Department of Circulation at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), thanked Moore for offering to lend a copy of Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 to a travelling exhibition she was organising, and noted that she had relayed to the museum’s director ‘that you had mentioned in conversation that this might be available to the Museum in the coming financial year at a very special price of between £600 and £700’.20 Hogben continued:

You will doubtless know from your experience at the Tate and the National Gallery [where Moore served as a Trustee] that it is impossible for any Government Department to promise in advance to make payments from funds which are subject to annual Parliamentary Vote. I can, however, say that we will be very keen to have this piece at that price, and that we could certainly hope if all goes well to buy this bronze from you at an early point in the financial year beginning April 1961.21

On 16 August 1960 Moore replied to Hogben saying, ‘I am pleased to read all you say ... and it is perfectly alright to leave open your acquiring the Three Motives Against Wall until after the beginning of your financial year’.22 The sculpture was delivered to the V&A in September 1960, and in May 1961 Hogben wrote to Moore asking whether his offer to sell the sculpture to the gallery at a favourable price was still open, adding, ‘form my own part, I cannot imagine any bill which it would give us greater pleasure to settle!’.23 Moore replied on 5 June offering the sculpture at the price of £650 before adding:

I hope that it will not be necessary to publish the price you are giving for it. My dealers get very upset if the press publishes a low price paid, since clients of theirs may have given several times that amount for the same piece of sculpture, and so think they have been overcharged, (in this case my dealers give me £2,000, and sell it at half as much again, or more.).24

The sculpture was acquired in June 1961 for £650, and on entering the V&A it was placed in the Department of Circulation. The department’s remit was to organise exhibitions of works from the collection at art schools and regional galleries so that students from around the country could view exemplary works of art without having to travel to London. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s an exhibition titled Henry Moore Sculpture and Drawings was available to art schools although this exhibition was made up of photographic enlargements. It is possible that Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 was included in the exhibitions Twentieth-Century Sculpture between 1960 and 1963 and Modern Sculpture and Sculptors Drawings available between 1967 and 1972.25

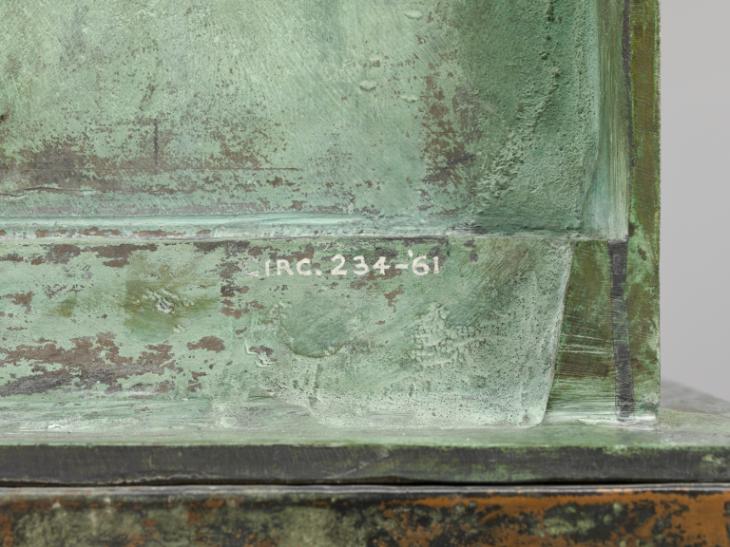

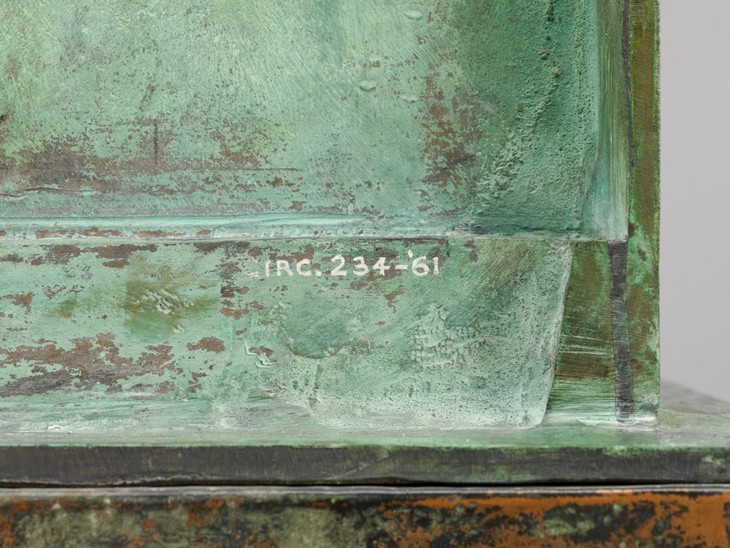

In 1983 Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 was one of seventy twentieth-century sculptures transferred from the V&A to the Tate Gallery. The transfer was made in order to rationalise the collections of both institutions, and was reciprocated by the Tate, which transferred to the V&A six of the earliest sculptures in its collection. The V&A identification number ‘CIRC.234–61’ is still visible on the rear of the sculpture (fig.20).

Detail of V&A identification number on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.20

Detail of V&A identification number on Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959

Tate T03763

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Other casts of this work may be found in the collections of the Henry Moore Foundation and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. A cast owned by the Art Institute of Chicago was de-accessioned and sold at Christie’s, New York, on 7 November 2007.26 Other examples are believed to be held in private collections.

Alice Correia

March 2013

Notes

[Judith Collins], ‘T.03763 Three Motives Against a Wall No.1’, The Tate Gallery 1984–86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982–84, London 1988, p.542.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.234.

Anita Feldman Bennet, ‘Figures in Architectural Settings – the UNESCO Experiments’ in David Mitchinson (ed.), Henry Moore and the Challenge of Architecture, Much Hadham 2005, p.22.

See, for example, Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.212–19, and Julian Stallabrass, ‘Three Motives against Wall No.1’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London, 2006, pp.256–8.

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, p.4.

Herbert Read, ‘Introduction’, in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, p.6.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.177.

Stallabrass 2006, p.256. See also Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Center) 1963–5, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, in Anne Wagner, Robert Sutton (eds.), Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2013, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research/content/1171994?project=4 , accessed 17 April 2015.

School Loans Prospectuses (MA/17/1); Travelling Exhibitions Available for Loan to Public Museums, Art Galleries and Public Libraries Prospectuses (MA/17/2); Exhibitions for Loan to Museums, Art Galleries and Libraries Prospectuses (MA/17/3/4); Exhibitions for Loan to Museums, Art Galleries and Libraries Prospectuses (MA/17/5), Victoria and Albert Museum Archive.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and the Values of Business Alex J. Taylor

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Three Motives Against a Wall No.1 1958, cast 1959 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www