Henry Moore OM, CH Relief Head 1923

Image 1 of 9

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief Head 1923© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Relief Head

1923

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

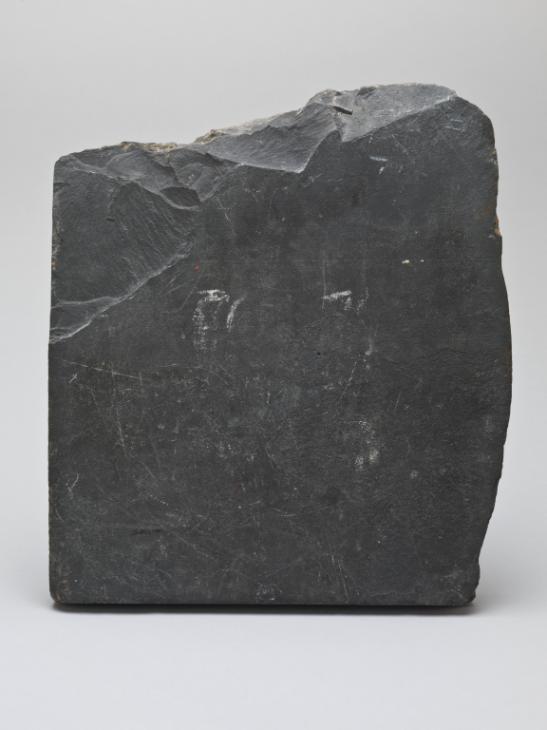

Made when Henry Moore was a student in London, Relief Head shows a man’s face incised into the surface of an almost square slab of slate. The sculpture is one of Moore’s earliest known works and suggests his interest in a number of artistic sources, ranging from the work of Paul Gauguin and Eric Gill to medieval art.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Relief Head

1923

Slate

314 x 278 x 30 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

L01764

Relief Head

1923

Slate

314 x 278 x 30 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

L01764

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by the artist’s sister Mary Spencer Moore, Wighton, Norfolk, in the early 1920s and no later than 1957; thence by descent.

Exhibition history

1961

Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, Marlborough Fine Art, London, June–July 1961, no.2.

1982–3

Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds, November 1982–January 1983, no.8.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, May–September 2004, no.3.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.3.

References

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, p.3, no.9.

1961

Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1961.

1982

Henry Moore: Early Carvings 1920–1940, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds 1982, p.22.

1984

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’, in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth-Century Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, vol.2, pp.595–614.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, p.41.

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, p.25.

Technique and condition

Moore made this work by carving a human face in low relief into a 30 mm thick slate slab, roughly fashioned into a square. Slate is formed from sedimentary rock that has been subjected to heat and pressure. Its characteristic feature is that it cleaves cleanly into flat sheets and so it has long been used in this form for tiles, blackboards and tombstones. Moore would have found this stone easy to obtain at an economical price from stonemasons but it would have lent itself to a relief carving rather than a sculpture in the round because of its propensity to split along cleavage planes.

Henry Moore

Relief Head 1923

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Relief Head 1923

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing chisel marks

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing chisel marks

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Both the right and bottom edges are cleanly sawn at right angles but rough planes of slate protrude on the top and left, and here Moore has marked out the square with deeply chiselled incised borders (fig.1). The hair is executed as a single carved line with a v-shaped cross-section, and the perimeter of the face has been deeply carved with vertical incisions of the chisel. The hollows of the cheeks are roughly marked out using a 4 mm wide chisel, whereas much finer chisel marks are visible on the eyelids (fig.2). The surfaces of the chin, lips, nose and forehead are sanded to a smooth finish.

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing fibrous deposit

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing fibrous deposit

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing traces of red and gold pigment

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing traces of red and gold pigment

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Close examination of the surface reveals traces of a pale brown, slightly fibrous deposit, especially in the crevices around the edges of the relief (fig.3). It is not clear what this might be. Traces of gold and red pigment are also clearly visible on two of the edges (fig.4) and to a lesser extent on the front surface. When the work was loaned to Tate in 1994, Judith Collins, then Assistant Keeper of the Modern Collection, annotated a reproduction of this work with the text: ‘Ptd edge by mother: removed by AG’..1 ‘AG’ can be identified as Anne Garrould, Moore’s niece and the daughter of the work’s original owner, Moore’s sister Mary. The note thus indicates that the paint had been added by Moore’s sister, but was later removed.

Henry Moore

Relief Head 1923 with stand

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Relief Head 1923 with stand

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The relief is intended for vertical display, although there are no fixings. When exhibited in Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings at Marlborough Fine Art in London in 1961 it was secured to a wall using brackets on the top and bottom edges. The sculpture now has a custom made wooden stand into which it is slotted (fig.5).

Lyndsey Morgan

July 2013

Notes

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', July 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Relief Head 1923 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Relief Head 1923 is one of Henry Moore’s earliest surviving sculptures. It was made while he was a student at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London, where he studied from September 1921 to June 1924. The relief sculpture depicts a male face surrounded by an oval line delineating hair, a hood, or possibly a halo. The outline of the face is not symmetrical; an irregular peak above the right eyebrow suggests an uneven hairline. The features of the face have been incised into the surface of the shallow, almost square slate stone. Both eyes are open, and appear to be looking straight ahead. The man’s right eye is slightly larger and is positioned slightly higher on the face than his left eye. Although his mouth is not wide, he has thick lips, which correspond to his heavy eyelids and brow. The identity of the man represented in Relief Head is unknown, and Moore probably constructed the image from his imagination.

On entering Tate’s collection in 1994 the adjective ‘relief’ was dropped from the title of this sculpture because it was then a gallery convention not to use words that identified the object type – painting, sculpture, relief – in the titles of artworks. The word ‘relief’ was restored to the title in 2013 in line with the sculpture’s listing in Moore’s catalogue raisonné, published in 1957. This sculpture is one of only two known works by Moore made in slate. The other, Head 1930 (private collection), is a three-dimensional, albeit narrow sculpture of a head and neck mounted onto a freestanding wooden square base.1 Slate is a sedimentary rock that is found globally, but in the UK is quarried in north Wales, Cumbria and Cornwall. The stone has a propensity to split into thin sheets, rendering it generally unsuitable for carving in three dimensions. Instead, slate is more commonly known as a building material, and is used for roof and floor tiles; its flat character has meant that it has also been used historically for tombstones. In a conversation with the curator and critic David Sylvester in 1963 Moore recalled that early in his career, owing to the expense of the stones and marbles conventionally used for sculpture, he would ‘buy odd random pieces of stone from any stonemason’, and this may help explain the use of slate for Relief Head 1923.2

In this sculpture the properties of the stone determined the carving techniques Moore was able to use. The facial features of the male face have been rendered through a series of inscribed lines and shallow incisions. In this instance, Moore used a combination of thin and wide chisels working directly into the stone. Most notable are the heavy chisel marks on the cheeks used to create texture, either to suggest facial hair or to convey the man’s gaunt features. Moore finished the work by sanding and smoothing the chin, lips, nose and forehead. Seen from the side it is clear that the facial features exist within a recessed, concave oval. As such, the shallow relief bears little resemblance to Moore’s other works from the period, such as Standing Woman 1922 (Tate L01765), which was carved in the round and emphasises three-dimensionality. Owing to the nature of the flat slate and the techniques used, the sculpture seems more akin to a woodblock used for printing than a carving.

Henry Moore

Head of the Virgin after Rosselli 1922–3

Marble

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Head of the Virgin after Rosselli 1922–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In 1947 Moore discussed his early career with the American critic John James Sweeny, recalling that:

my aims as a ‘student’ were directly at odds with my taste in sculpture. Already, even here a conflict had set in ... there was a bitter struggle within me, on the one hand, between the need to follow my course at college in order to get a teacher’s diploma and, on the other, the desire to work freely at what appealed most to me in sculpture.8

Moore found a solution through compromise; he led a double life, drawing and modelling classical forms according to the curriculum during term-time, and directly carving his own sculptures in the holidays.9 From 1922 to 1925 Moore often stayed with his sister Mary Spencer Moore (later Garrould) in Wighton near the Norfolk coast during college vacations. A number of his early non-academic sculptures, including Dog 1922 (The Henry Moore Foundation) and Mother and Child 1922 (private collection), were carved in her garden in these years.10 Although it is not known where Moore made Relief Head, it is probable that he made it during one of his Norfolk holidays. Moore’s sister Mary was identified as its owner in the artist’s catalogue raisonné in 1957, and she may well have owned it from the time Moore made it.

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing traces of red and gold pigment

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of Relief Head 1923 showing traces of red and gold pigment

L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

On long-term loan to Tate L01764

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

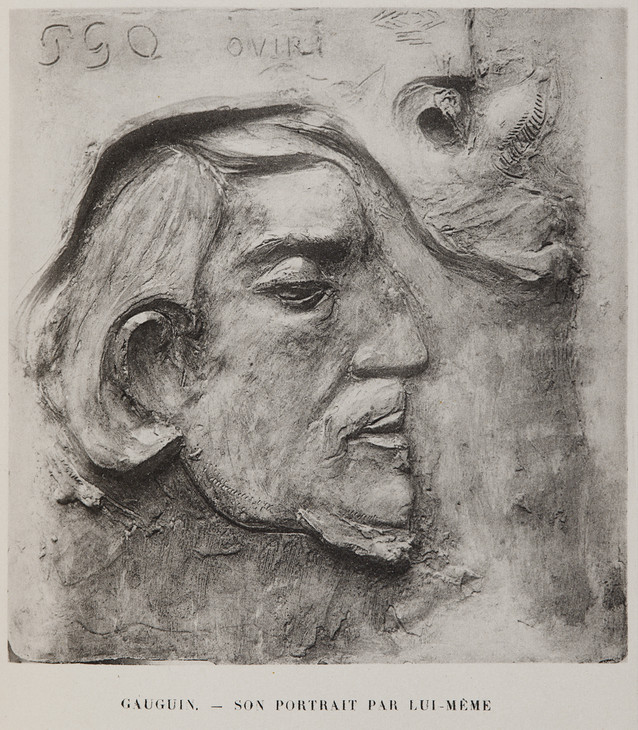

Moore made only two known statements about this work. In 1984 the art historian Alan Wilkinson recounted how, in the early 1970s, Moore described Relief Head as ‘Gauguinesque’.13 Wilkinson supplemented this reference to the French artist Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) with an account from Ann Garrould that in 1983 Moore had stated that, ‘I did not realise how much I’d been influenced by Gauguin in this work’.14 Relief Head was exhibited only twice in Moore’s lifetime and due to its limited exposure it has received almost no critical attention to date. However, Moore’s late acknowledgement of the previously unrecognised influence of Gauguin is significant. Moore had been introduced to the work of Gauguin sometime between 1919 and 1921 when he attended Leeds School of Art, where he came into contact with Sir Michael Sadler (1861–1943), the Vice-Chancellor of Leeds University, who encouraged students to study his personal art collection.15 As Moore recalled in 1973, ‘Sadler had a Gauguin, a wonderful Gauguin, and a few other things. It was the Gauguin and a few ones like that which impressed me most. It opened up a world that was other than the Victorian, academic, art-school world’.16

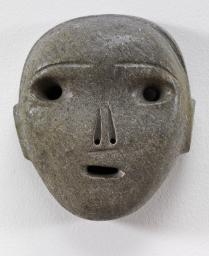

In 1984 Wilkinson suggested that the most likely source for Relief Head was Gauguin’s painted plaster relief Oviri (Self-Portrait) 1894, illustrated in Charles Morice’s book Paul Gauguin, published in Paris in 1911 (fig.3).17 However, the retrospective surprise Moore expressed in 1983 when he noted Gauguin’s influence on Relief Head suggests that Moore had not attempted to emulate a specific work by Gauguin while he was carving the sculpture. Moreover, the obvious compositional differences between Relief Head and Oviri (Self Portrait) render Wilkinson’s proposal unconvincing: Gauguin’s self-portrait is in profile and was carved in plaster, a far more malleable medium than slate. Instead, Gauguin’s influence on Moore was more generally stylistic, offering an alternative to the representational accuracy of classical Greek, Roman, and Renaissance art. Indeed, for many artists working in the first decade of the twentieth century, Gauguin’s art provided an example of how to break free from the narrow confines of the academic artistic conventions promoted by institutions such as the RCA.18 Gauguin’s art was admired by Moore and others for the ways in which figures are distorted, for the use of non-naturalistic colour and for the prioritisation of styles and forms derived from archaic and non-Western art. In his paintings Gauguin rejected traditional techniques of modelling and shading used to render space and forms illusionistically in favour of areas of pure colour that flattened space and drew attention to the two-dimensionality of the picture plane. Forms are often demarcated by bold outlines reminiscent of stained glass windows. This simplified style was also used by Gauguin in his carvings and woodcuts where the evidence of the artist’s working processes are clearly discernable.

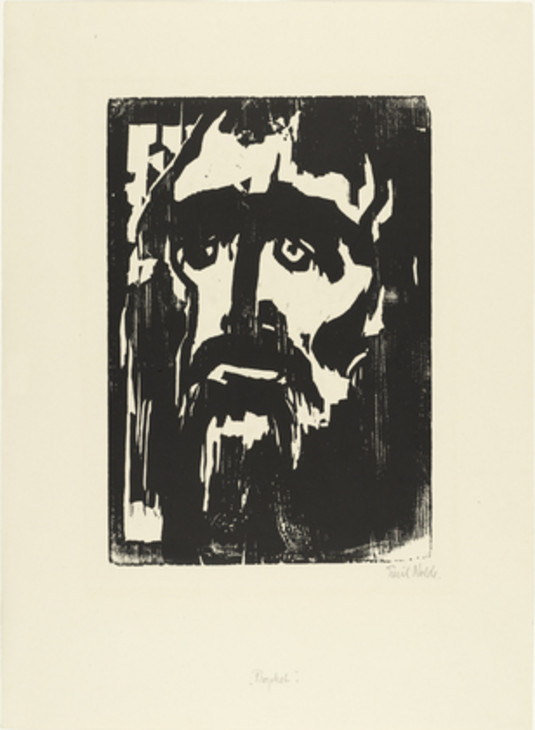

Emil Nolde

Prophet 1912

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Nolde Stiftung Seebüll, Germany

Fig.4

Emil Nolde

Prophet 1912

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Nolde Stiftung Seebüll, Germany

Such was the influence of Gauguin’s work on early twentieth-century European art that it is possible that Moore came to absorb his formal and stylistic innovations vicariously through the work of other artists. For example, although Moore never directly drew links between his work and that of the German expressionist group Die Brücke, Relief Head is reminiscent of works created by artists such as Emil Nolde (1867–1956) from the 1900s and 1910s. Although they were created in different mediums, Moore’s Relief Head and Nolde’s woodcut Prophet 1912 (fig.4) share a number of characteristics with Gauguin’s self portrait. All three works present a man’s face tightly framed within a demarcated space, executed using bold lines and shapes. In each work the man’s brow is furrowed and the face is elongated, with a prominent chin. Beyond immediate formal similarities, Nolde and Moore appear to have followed Gauguin’s example of rejecting the naturalism and crisp finesse of academic art. In that it shares Gauguin’s legacy with works by other European artists, Moore’s Relief Head can be positioned within a broader narrative of European modernism and specifically within the tendency known as primitivism, which inflected much of the art produced in western Europe during the first half of the twentieth-century.19

Primitivism is an over-arching term used by art historians to describe an aesthetic tendency of early twentieth-century European art that sought to emulate the forms and values of non-Western art, which were deemed to be more authentic than the sophisticated classicism of the European fine art tradition. This included tribal art from Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands, as well as prehistoric and medieval European art. By looking to non-Western artistic sources or historical European examples, artists found ways to challenge the predominance of classical artistic conventions at the turn of the century. Moore’s interest in primitivism dates from his time as a student at Leeds School of Art, where in 1920 he read Roger Fry’s influential book Vision and Design (1920). Fry was a founding member of the Bloomsbury Group of artists and writers and a highly regarded art critic. His book included chapters on African, Islamic and ancient American arts and proposed that the aesthetic experiences generated by these non-Western, ‘primitive’ art forms were more authentic than those of European classicism, with its focus on anatomical accuracy and technical virtuosity. As the art historian Christopher Green has suggested, for Fry, the turn to primitive art ‘offered a stimulus for rebuilding the broader terms of the European tradition’.20 Moore later recalled that ‘Fry opened the way to other books and to the realisation of the British Museum. That was the beginning really’.21 It is likely that Moore’s interest in Fry’s ideas were supported by Michael Sadler in Leeds. In January 1911 Sadler had attended Fry’s lecture on modern art that accompanied his major exhibition Manet and the Post Impressionists, held at the Grafton Galleries in London. Soon after visiting the exhibition Sadler acquired his painting by Gauguin.22

Significantly, under Fry’s editorial leadership, the Burlington Magazine, a leading arts periodical, regularly featured articles on modern and primitive arts throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Importantly, as well as articles on, for example, Peruvian pottery or Indian sculpture, Fry and the magazine classified early Christian, Byzantine and medieval European art as ‘primitive’.23 In an article published in the magazine in 1920, the French critic André Salmon linked the expressive qualities of African art with those of European medieval sculpture.24 As such, by the time Moore was working on Relief Head, the sculpture and stained glass of European cathedrals such as Chartres in France or Chichester in England, would have been understood under the rubric of primitive art. On his arrival in London in 1921 Moore made a point of ensuring that he read the leading art magazines and periodicals of the day, and would certainly have been aware of the discussions taking place within the pages of the Burlington Magazine.25

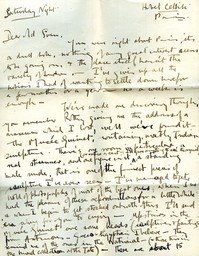

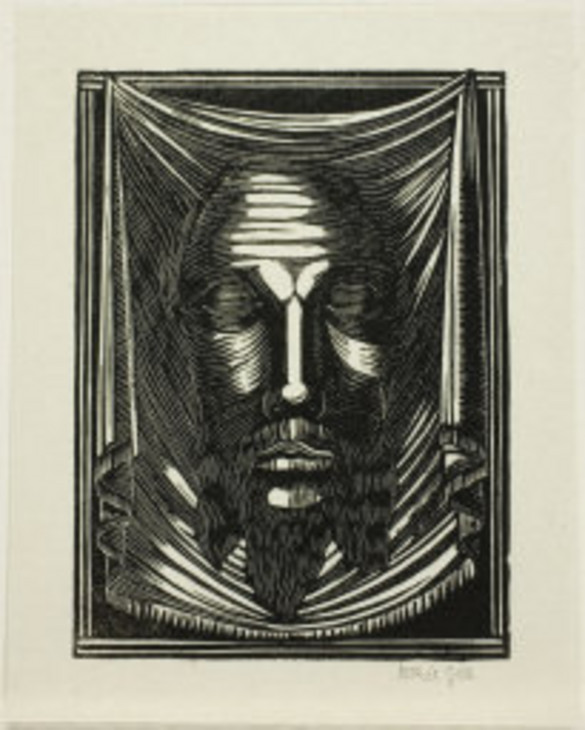

In his art criticism Fry championed artists who he regarded as working in a primitivist aesthetic, including the English sculptor Eric Gill (1882–1940). Gill had become well-known before the First World War and when Moore arrived in London in 1921 he was one of the contemporary sculptors whose work Moore sought out. Although Moore recognised the influence of Gauguin in Relief Head, Gill’s etchings of religious subjects may also have provided a reference point for the sculpture. In 1923, the year he made Relief Head, Moore saw a large number of Gill’s carvings and woodcuts in the collection of Charles Rutherston (1866–1927).26 Rutherston was the brother of Sir William Rothenstein, the principal at the RCA and the first collector of Moore’s sculpture.27 Rothenstein had introduced Moore to his brother and in 1923 Moore visited Rutherston’s home in Bradford to view his large collection of primitive and modern art, which included examples of African and Egyptian art and carvings by contemporary British sculptors such as Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) and Frank Dobson (1886–1963). In a letter dated August 1923 addressed to his old school teacher Jocelyn Horner, and written from his sister’s home in Norfolk, Moore recounted his visit to Rutherston’s home noting that his host owned most of Gill’s woodcuts, concluding that ‘you can guess how much I enjoyed & saw in those four days’.28

Gill’s primitivism was heavily informed by medieval Christian art. He had been raised a Calvinist Methodist and converted to Roman Catholicism in 1913 and the depiction of religious subjects in his sculpture after this date stemmed in large part from his religious beliefs.29 However, Gill also looked towards modern art for inspiration and a number of his sculptures, prints and drawings were influenced by Gauguin’s flat, linear style and the religious themes found in the French artist’s paintings made in Pont Aven in the 1880s. In particular, the composition of Gill’s Crucifixion 1909–10 (Tate N03563) depicting Christ on the cross was directly informed by Gauguin’s The Yellow Christ 1889 (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo).30 Gill’s carved relief echoes the overall composition of Gauguin’s painting, including the bearded, tilted face of Christ. It is possible that Gill’s own references to Gauguin reinforced the ‘Gauguinesque’ qualities found in Moore’s work.

Eric Gill

The Holy Face 1917

Art Institute Chicago

Fig.5

Eric Gill

The Holy Face 1917

Art Institute Chicago

Raising of Lazarus c.1125–50, cast 1864

Victoria and Albert Museum

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.6

Raising of Lazarus c.1125–50, cast 1864

Victoria and Albert Museum

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

I stood before them for a long time. They were just what I wanted to emulate in sculpture: the strength of directly carved form, of hard stone, rather than modelled flowing soft form ... In the Chichester sculptures there is deep human feeling. I think the sense of suffering and tragedy is chiefly given through the heads. Look particularly at the head of Christ in the Raising of Lazarus. The eyebrows and the eyes are sloped steeply downwards from the centreline of the face expressing intense grief.36

Although the exact date of Moore’s visit to Chichester is uncertain, it is possible that Relief Head was made partly in response to his experience of seeing the Raising of Lazarus, whether that be from observing the original in situ, or from studying the plaster cast of the sculpture in the Victoria and Albert Museum on one of his many student visits. The sunken cheeks and long gaunt faces of the figures in the Raising of Lazarus are echoed in the elongated facial features of Relief Head, while the slightly protruding conjoined brow and recessed eyes paraphrase the twelfth-century faces. The man’s piercing stare also emulates the focused looks of the various figures in the Lazarus scene. These similarities suggest that Moore was seeking to emulate what he regarded as the sorrowful, emotional content of the medieval relief. While in later work Moore moved away from representing individual facial expressions in favour of more universal emotions, here the man’s returned gaze invests the sculpture with a personalised sensibility.

Relief Head is the property of a private collection and has been on loan to Tate since 1994.

Alice Correia

November 2012

Notes

Head 1930 is illustrated in David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, 5th edn, London 1988, p.54.

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester, ‘Henry Moore talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, pp.305–7 Tate Archive TGA 200861, pp.19–20. An edited version of this conversation was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963.

A pointing machine is a measuring tool used by sculptors to make like-for-like copies of sculptures. The device includes adjustable rods on an armature that are used to measure specific points on the surface of a modelled sculpture. The tool measures the width, height and depth of these points from a chosen position and these dimensions are then used to accurately carve into a block of stone or wood. Each time a point (or measurement) is taken, a small hole is drilled into the corresponding block of stone to indicate the point to which the sculptor should carve. The first point of reference is the highest relief point; on a sculpture of a head this might be a protruding nose. This ensures that the sculptor does not carve away too much material. Carvings made with the use of a pointing machine are often pockmarked, where the point has been drilled fractionally too deep. For an example of a sculpture made with a pointing machine with visible point marks, see Auguste Rodin, The Kiss 1901–4 (Tate N06228).

See Ian Dejardin, ‘Catalogue’, in Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, p.37.

For Domenico Rosselli, Virgin and Child 1450–98, see http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O137490/virgin-and-child-relief-rosselli-domenico/ , accessed 15 November 2012.

See John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.33. Moore’s subversive act when making the work is possibly one of the reasons why the work survived while his other pieces of coursework did not.

Henry Moore quoted in John James Sweeney, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.46.

See John and Véra Russell, ‘Conversations with Henry Moore’, Sunday Times, 17 December 1961, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.47.

A photograph of Moore dated c.1922–3 standing in his sister’s garden next to Dog 1922 and Mother and Child 1922 is reproduced in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.150.

However, in an installation photograph of the Marlborough exhibition the sculpture does not appear to be painted. Even though the photograph is black and white, this is still clear.

Alan Wilkinson, ‘Henry Moore’, in William Rubin (ed.), Primitivism in Twentieth-Century Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1984, vol.2, p.599.

Sir Michael Sadler was an important influence on Moore and was a prominent early collector of his sculpture. At Leeds Sadler was active in the University’s arts, drama and music societies, and he established a programme of public lectures on the arts, inviting speakers including Roger Fry. Sadler also gave lectures on artists such as Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh, based on works in his own collection. Sadler was at the centre of artistic activities in Leeds and as an educationalist made his collection available as much as possible, frequently lending and showing items to artists and students in the city. In later life Moore acknowledged the importance of Sadler to his artistic education noting that ‘he really knew what was going on in modern art’. See Wilkinson 2002, p.44. Henry Moore’s sculpture Figure 1931 (Tate T00240) was formerly in Sadler’s collection.

Moore cited in Donald Carroll, The Donald Carroll Interviews, London 1973, p.35, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

Wilkinson 1984, p.599. On the basis of Wilkinson’s research the art historian Christa Lichenstern went on to compare Head with Gauguin’s carved relief head Tehura, Also Called Teha'amana 1891–3 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) although this comparison is less convincing. Tehura, Also Called Teha'amana is a wooden mask-like relief sculpture depicting a Tahitian girl and bears no similarity to Moore’s Head in subject matter or form. In making the comparison it possible that Lichenstern was attempting to link Moore and Gauguin and their shared application of direct carving. See Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, p.25 and p.420 note 43. For Gauguin’s Tehura, Also Called Teha'amana 1891–3, see http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/index-of-works/resultat-collection.html?no_cache=1&zoom=1&tx_damzoom_pi1%5Bzoom%5D=0&tx_damzoom_pi1%5BxmlId%5D=015289&tx_damzoom_pi1%5Bback%5D=en%2Fcollections%2Findex-of-works%2Fresultat-collection.html%3Fno_cache%3D1%26zsz%3D9 , accessed 26 July 2012.

Christopher Green, ‘Expanding the Canon: Roger Fry’s Evaluations of the “Civilized” and the “Savage”’, in Christopher Green (ed.), Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art, exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London 1999, p.126.

See Colin Rhodes, ‘Burlington Primitive: Non-European Art in The Burlington Magazine Before 1930’, Burlington Magazine, vol.146, no.1211, 2004, pp.98–104.

In his interview with Donald Carroll Moore recalled going to Zwemmer’s bookshop in London and reading the magazines and books. See Carroll 1973, p.35, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

Rutherston, who was the Bradford-born son of German-Jewish immigrants anglicised his surname in 1916, while his brother retained the family name.

See Richard Cork, Wild Thing: Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska, Gill, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 2009, p.43. For an image of Gauguin’s The Yellow Christ, see http://www.albrightknox.org/collection/collection-highlights/piece:gauguin-yellow-christ/ , accessed 26 July 2012.

For examples of sculpture by Alan Durst and Vernon Hill see Benedict Read and Peyton Skipwith, Sculpture in Britain Between the Wars, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1968.

While in Paris in the spring of 1922 Moore saw Auguste Pellerin’s collection of paintings by Paul Cézanne. On the experience of seeing Cézanne’s painting, Moore stated that it ‘was like seeing Chartres Cathedral’; see Russell 1961, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.50. To date this remark has been used by scholars to demonstrate the huge impact Cézanne had on Moore’s artistic development. However it is also important to recognise that visiting Chartres was itself a formative artistic experience.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and Direct Carving: Technique, Concept, Context Sarah Victoria Turner

- Circling Each Other: Henry Moore and Adrian Stokes Richard Read

- Life Forms: Henry Moore, Morphology and Biologism in the Interwar Years Edward Juler

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Relief Head 1923 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www