Henry Moore OM, CH Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5

Image 1 of 13

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Maquette for Madonna and Child

1943, cast 1944-5

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This small bronze sculpture by Henry Moore is the preparatory study for a larger than life-size stone sculpture, Madonna and Child 1943–4, carved for St Matthew’s Church in Northampton. The sculpture developed from Moore’s wartime Shelter Drawings but also drew upon Renaissance depictions of the Holy Family. When the full-size sculpture was unveiled it provoked considerable controversy, prompting public debates about the suitability of modern art styles for religious subjects.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Maquette for Madonna and Child

1943, cast 1944–5

Bronze

155 x 85 x 70 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on side of base

In an edition of at least 5 plus one artist’s copy

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1945

N05602

Maquette for Madonna and Child

1943, cast 1944–5

Bronze

155 x 85 x 70 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on side of base

In an edition of at least 5 plus one artist’s copy

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1945

N05602

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1945.

Exhibition history

1948

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice, June–September 1948, no.27c.

1971

Faith Alive, Northampton Central Museum and Art Gallery, Northampton, March–April 1971.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, p.62.

References

1944

Geoffrey Grigson and Eric Newton, ‘Henry Moore’s Madonna and Child’, Architectural Review, vol.95, no.569, May 1944, pp.137–40 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced pp.137–9).

1944

Walter Hussey, ‘Correspondence [Letter to the Editor]’, Architectural Review, vol.96, no.570, July 1944, p.1.

1944

Sir Kenneth Clark, ‘A Madonna by Henry Moore’, Magazine of Art, vol.37, no.7, November 1944, pp.247–9.

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944 (terracotta original reproduced pl.107b).

1945

Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Thoughts on Henry Moore’, Burlington Magazine, vol.86, no.503, February 1945, pp.47–9.

1945

Philip Hendy, ‘Art – Henry Moore’, Britain Today, no.106, 1945, pp.34–5 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced).

1946

Mary Sorrell, ‘Henry Moore’, Apollo, vol.44, November 1946, pp.116–18 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced p.116).

1946

James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946, reproduced pl.74.

1948

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture II’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1 948, pp.186, 189–95.

1949

Walter Hussey, ‘A Churchman Discusses Art in the Church’, Studio, vol.138, no.678, September 1949, pp.80–1, 95.

1951

Henry Moore, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC, 30 April 1951, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8801.shtml, accessed 13 January 2014.

1954

Lawrence Alloway, ‘The Siting of Sculpture’, Listener, 17 June 1954, pp.1044–6 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced p.1044).

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1948, London 1957, p.13, no.224 (terracotta original reproduced p.138).

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, p.134.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.137–9 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced pls.110–11).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.151–7 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced nos.132–4).

1966

Donald Hall, Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, London 1966 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced p.102).

1967

Henry Moore: One Yorkshireman Looks at His World, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC2, 11 November 1967, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8807.shtml, accessed 7 February 2014.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.90–9.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.157–65 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced pp.157–61; terracotta original reproduced p.162).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, 1968, revised edn, London 1973, pp.119–23.

1975

Kenneth Clark, ‘Dean Walter Hussey: A Tribute to his Patronage of the Arts’, in Chichester Nine Hundred, Chichester 1975, pp.68–72.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.23.

1979

John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced p.103).

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981 (another cast reproduced no.160).

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced p.62.

1985

Walter Hussey, Patron of Art: The Revival of a Great Tradition Among Modern Artists, London 1985 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced front cover).

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, pp.222–3 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced p.222 and front cover).

1992

Garth Turner, ‘Aesthete, Impresario and Indomitable Persuader: Walter Hussey at St Matthew’s, Northampton, and Chichester Cathedral’, in Diana Wood (ed.), The Church and the Arts, Oxford 1992, pp.523–35.

1992

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Henry Moore: Mother and Child’, in Henry Moore: Mutter und Kind / Mother and Child, exhibition catalogue, Käthe Kollwitz Museum, Cologne 1992, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Moore.pdf, accessed 13 December 2013.

2003

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, revised edn, London 2003 (Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced p.216).

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004 (another cast reproduced p.54).

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.207–9 (another cast reproduced p.208).

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008 (another cast reproduced p.136; Madonna and Child 1943–4 reproduced p.165).

Technique and condition

This maquette of a seated mother holding a child is a solid bronze cast with no hollow cavity. The original model for this sculpture was made in clay and would have been used to make a mould from which the final bronze version could be cast. Moore made small impressions into the clay model to denote facial features, fingers and drapery in the clothing, which are replicated in the bronze sculpture. The level of surface detail on the bronze suggests that it was made using the traditional lost wax casting technique. Although it is possible to see where casting flashes have been filed away and chased to blend with the surrounding surface, there is otherwise little post-cast finishing.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child (side view) 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05602

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child (side view) 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05602

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of signature on Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05602

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of signature on Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05602

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The bronze surface has been coloured using chemical patination techniques. First, a slightly transparent brown colour was applied over the entire surface, followed by a more opaque green colour, which was then rubbed back on the high points using a light abrasive to pick out the details of the form (fig.1). The patina was then finished with a coating of wax. The brown base colour is often used on bronzes and is likely to have been applied using a solution of potassium polysulphide (otherwise known as ‘liver of sulphur’) in water. There are many different patina recipes used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts.

The signature ‘MOORE’ was inscribed on the side of the base using a sharp point, possibly into the clay model or the pre-cast wax (fig.2). The maquette is in generally good condition and has not required treatment.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Robert Sutton, ‘Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, revised by Alice Correia, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Maquette for Madonna and Child is a small bronze sculpture cast from a study originally modelled in clay. It depicts a woman seated on a low bench with a child on her lap (fig.1). She is dressed in a long sleeveless robe and sits with her knees apart. The child sits upright with its back to the woman’s chest, balanced on her right thigh and supported by her hands, which rest on the child’s right shoulder and chest. The woman’s head is turned slightly towards her right while the child faces straight ahead.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05602

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05602

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Hornton Stone

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The sculpture was intended as a representation of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ, and is one of a series of preparatory maquettes sculpted by Moore in the spring and early summer of 1943. These maquettes were made to test designs for a large stone sculpture of the Madonna and Child, commissioned to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the consecration of St Matthew’s Church in Northampton. This was Moore’s first major public commission and provided the artist with an opportunity to develop his long-standing interest in the mother and child theme in line with more traditional representations of the subject, which suited the commission’s demands. Of the five maquettes presented to the commissioner in July 1943, this design was ultimately chosen to be enlarged into the final sculpture, which was carved in Hornton stone and dedicated in St Matthew’s Church on 19 February 1944 (fig.2).

The commission

The commission came about after the vicar of St Matthew’s, the Reverend Walter Hussey, saw a number of Moore’s Shelter Drawings in an exhibition at the National Gallery, London, in the autumn of 1942. The exhibition had been organised by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC), a governmental body set up under the auspices of the Ministry of Information to boost British morale during wartime by commissioning images of British endurance from recognised artists. In 1940, having been forced to give up sculpture due to a lack of available materials, Moore produced a series of drawings of women and children sheltering in the London Underground during the Blitz, which he showed to Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery and Chairman of the WAAC, who invited him to become an Official War Artist.

Although some visitors to the National Gallery found that Moore’s shelter drawings did not accurately convey the reality of their wartime experiences, on his return to Northampton, Hussey signalled his admiration for the work to Harold Williamson, Director of the Chelsea School of Art, which had been relocated to Northampton in 1941 to escape the bombing in London.1 As Hussey recalled in his memoirs, ‘I remember shaking my finger at him and saying: “That is the sort of man who ought to be working for the Church – his work has the dignity and force that is desperately needed today”’.2 Moore had taught sculpture at the Chelsea School of Art since 1933 and so was well known to Williamson, who arranged for the two to meet the following week when Moore was visiting Northampton. It was then that Hussey proposed the commission to Moore: ‘I asked him whether he thought he would be interested in the project; he replied that he would, though whether it could go further, whether he could and would want to do it, he just couldn’t say at present’. Hussey also asked Moore if he felt able to believe in the commission, to which the artist responded ‘Yes, I would. Though whether or not I should agree with your theology, I just do not know. I think it is only through our art that we artists can come to understand your theology’.3 Moore’s attitude to Christianity was ambivalent; he stated in 1973 that ‘although I was baptised and made to go to church as a boy, I am not a practicing Christian’.4

In early December 1942 Hussey wrote to Moore enquiring whether he had considered the scheme any further. Hussey was at pains to express his desire for Moore to undertake the commission while also respecting the sensibilities of both the artist and the congregation of St Matthew’s. A sculpture that offended the ‘religious susceptibilities’ of the congregation was to be avoided, but he was also anxious that Moore should not have to compromise his artistic integrity.5 Moore replied on 6 March 1943, stating, ‘I’ve not forgotten the scheme and I’m very keen to begin thinking seriously about it and I think that in a couple of weeks’ time I shall get the chance to begin playing about making note-book sketches to get ideas for it’.6 On 29 April Moore wrote to Hussey confirming that he had at last ‘begun notebook sketches for it’.7

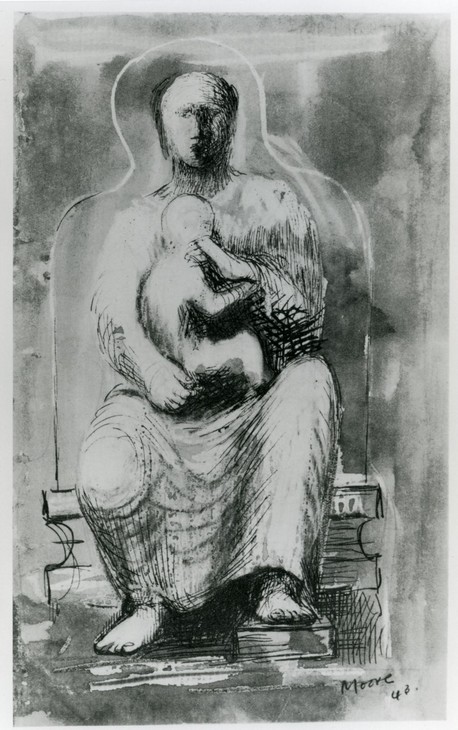

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943

Coloured crayon, wax crayon, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

182 x 113 mm

Private collection

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943

Private collection

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photograph of six terracotta maquettes for Madonna and Child 1943

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

Fig.4

Photograph of six terracotta maquettes for Madonna and Child 1943

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

I was able to begin 4 or 5 days ago, translating some of the small note-book drawings I’d made, into small clay models and I’ve now got 4 clay models (each about 4” high) on the go. I don’t know yet what I think of these, and shan’t until each one has had a few more hours spent on it. But anyhow there are 4 or 5 small drawings in the note-book which I want to try out in solid forms in clay too, so it’s going to be another 2 or 3 weeks, I’m afraid.13

When seen together, the maquettes reveal how Moore experimented with the position and size of the Christ child and the pose of the Madonna, and testify to Moore’s growing interest in drapery. Moore later acknowledged that the folds of the mother’s dress in the maquettes were directly informed by his Shelter Drawings: ‘I had never used drapery in sculpture prior to making the shelter drawings. Then I saw sculptural form in the folds of the material and employed it’.14 The fact that Moore knew where the final sculpture was to be positioned in St Matthew’s Church also informed how he modelled the figures. The allocated site was against a wall, and as such Moore paid little attention to the backs of his maquettes. Discussing the final sculpture in 1944, Moore explained that ‘the Madonna’s head is turned to face the direction from which the statue is first seen, in walking down the aisle, whereas one gets the front view of the Infant’s head when standing directly in front of the statue’.15 In his discussion of the commission, the art critic Herbert Read noted that the final sculpture had to confirm to what he called ‘the law of frontality’, by which Moore had to convey mass and volume without ‘an all round perambulation’.16

Of the twelve maquettes produced in clay five were selected by Moore to show to Hussey on 23 July 1943. This maquette was one of the five selected and was Moore’s preferred design, but he informed Hussey that he would ‘be prepared to base the finished statue’ on any one of the five.17 The production of multiple models provided Hussey not only with an element of choice but also a clearer idea of what the finished work might look like. After viewing the five proposed maquettes in London and noting Moore’s preference, Hussey took them back to Northampton to show members of St Matthew’s Parochial Church Council, who ‘agreed to the one preferred by the artist’.18 This Maquette for Madonna and Child was chosen as the design for the final sculpture, which Moore carved throughout the latter half of 1943 and early 1944. In the brochure published in late 1943 to announce the commission, Moore wrote that, ‘of the sketches and models I have done, the one chosen has, I think, a quiet dignity and gentleness’.19

However, following the unveiling of the full-size Madonna and Child an unnamed journalist writing in the Northampton Independent reported that ‘there were few at last Saturday’s unveiling who could repress a gasp of astonishment when the drapery fell to reveal the work ... Thereafter, astonishment was submerged by a flood of emotional reactions varying from rapt admiration, in the upper reaches, down to a torrent of rank disgust in the lower, according to individual tastes’.20 In the same edition of the newspaper the editors published one of a number of criticisms sent in by readers:

The much-discussed statue of the Madonna and Child is, in my opinion, a monstrosity better suited for a museum than an Anglican church and is more calculated to distract rather than deepen devotion. The physique of the Madonna appears to my, perhaps untutored, eyes to be out of all proportion to any human being who has ever lived. One likes to think of the Madonna as an ordinary but noble specimen of womanhood and not a physical freak, and it is, to say the least, disturbing to me – as I know it is to other members of the Church of England – to find that our hallowed places of worship are in peril of being turned into exhibitions of the nightmare creations of the ultra-modern impressionist school of art. Posterity may praise the statue, but candidly, I confess it leaves me not only disappointed but completely depressed.21

But it was not just the ‘untutored’ who raised concerns over Moore’s sculpture. In May 1944 the critics Geoffrey Grigson and Eric Newton voiced their reservations about Moore’s sculpture in the journal Architectural Review. While they agreed that the work was an imaginative and successful example of modern art, they questioned its success as a religious work of art. Grigson stated that looking at Moore’s sculpture left him ‘uneasy’ because he could not ‘see Henry Moore’s belief’.22 He suggested that since the sculptor was not a practicing Christian, the sculpture could not be a true expression of faith. Newton concluded that although Moore’s Madonna and Child was ‘both a descendent of and a challenge to a thousand enthroned Madonnas of the past’, she would be seen in the future as a manifestation ‘of a deep seriousness somehow inherent in the mid-twentieth century’, rather than as an inherently religious icon.23

Sources and development

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1932

Green Hornton stone

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, Norwich

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1932

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, Norwich

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

I began thinking of the ‘Madonna and Child’ for St Matthew’s by considering in what ways a Madonna and Child differs from a carving of just a ‘Mother and Child’ – that is by considering how in my opinion religious art differs from secular art. It’s not easy to describe in words what this difference is, except by saying in general terms that the ‘Madonna and Child’ should have an austerity and a nobility and some touch of grandeur (even hieratic aloofness), which is missing in the ‘everyday’ Mother and Child idea.25

To create his Mother and Child sculpture in 1932 Moore used the technique of direct carving, which involved working directly on the stone without reference to a model or preparatory sketches. In the early 1930s Moore and other contemporary sculptors, including Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping, believed that by working directly on the stone, and in response to its particular physical properties, a sculptor could create a work of art that had more authenticity than one that eschewed the true qualities of its material. Moore later recalled that he ‘liked the different mental approach involved’ in direct carving, ‘that you begin with the block and have to find the sculpture that’s inside it’.26 By making small clay maquettes of the Madonna and Child prior to making the full-size stone carving, Moore therefore departed from this pre-war working method.

Masaccio

Madonna and Child 1426

Egg tempera on wood

1348 x 735 mm

National Portrait Gallery

Fig.6

Masaccio

Madonna and Child 1426

National Portrait Gallery

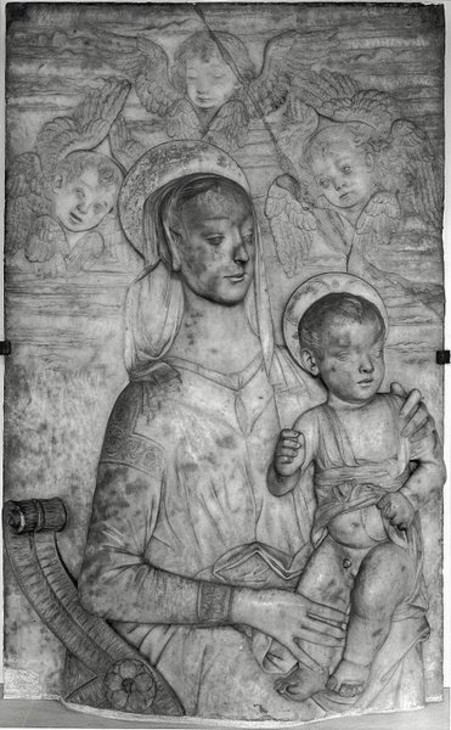

Domenico Rosselli

Virgin and Child 1450–98

Marble and gilt

1040 x 6550 x 1450 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig.7

Domenico Rosselli

Virgin and Child 1450–98

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1946 the critic Mary Sorrell proposed that Moore’s Madonna and Child drew heavily upon Italian Renaissance depictions of the subject, noting that, ‘The perfect foundation was Masaccio, idealistic but at the same time human, and he again stimulated the sculptor by his simple and unerring form’.27 Moore’s Madonna and Child certainly shares compositional affinities with Masaccio’s Madonna and Child 1426 (fig.6), in which the infant Jesus is positioned on his mother’s knee, looking straight out towards the viewer while the Virgin turns to the side. Moore was familiar with this painting, which is in the National Gallery, London, and expressed his admiration for Masaccio’s work in his 1937 essay ‘The Sculptor Speaks’.28 Moore had also studied examples of fifteenth-century Italian sculpture while he was a student at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London in the early 1920s, during which time he carved a copy of the Virgin’s head from Domenico Rosselli’s relief sculpture Virgin and Child 1450–98 (fig.7).29 On graduating from the RCA in 1924 Moore was awarded a six-month travel grant intended to facilitate the study of the arts of Renaissance Italy. Although he wanted to spend all of his time in Paris, Moore nonetheless travelled throughout Italy during the first part of 1925 and was impressed by the wall paintings of Giotto, Orcagna, Lorenzetti and Taddeo Gaddi, as well as Masaccio. However, in 1947 he recalled that,

Six months’ exposure to the masterworks of European art which I saw on my trip had stirred up a violent conflict with my previous ideals. I couldn’t seem to shake off the new impressions, or make use of them without denying all I had devoutly believed in before. I found myself helpless and unable to work ... Still the effects of that trip never really faded. But until my Shelter Drawings during the war I never seemed to feel free to use what I learned on that trip to Italy in my art – to mix the Mediterranean approach comfortably with my interest in the more elementary concept of archaic and primitive peoples.30

By depicting drapery and evoking the postures and poses of historical examples of the Madonna and Child, Moore found that it was possible to draw upon the idealised representations of Renaissance art without compromising his own ‘elementary’ figurative style. In 2003 the art historian Margaret Garlake proposed that Moore’s turn to figuration with the Shelter Drawings and the Northampton commission ‘encouraged him to acknowledge that a more easily read figurative art was capable of being both radical and popular’.31 According to the art historian Christa Lichtenstern, the wartime context of the commission may also have informed how Moore chose to represent his Madonna and Child:

with the war still continuing unabated, it seems that Moore poured all his longing for peace into this work. And he found this peace in his representation for the balance between powerful and solid forms and their spiritual content, between dynamism and stasis, between the fixed configuration of the bodies and the nuanced wealth of expression in their faces. It is this grave harmony that marks out the Northampton Madonna as the legitimate successor to the Madonnas of Giotto and Masaccio, despite the intervening centuries.32

Casting the maquettes

In Moore’s catalogue raisonné the clay studies for Madonna and Child are described as being made in terracotta.33 In 1963 Moore addressed any misunderstanding, explaining that ‘the original maquettes of the MADONNA AND CHILD ... sculptures were all modelled direct in clay and then baked, and so became terra-cottas. It was from these terra-cottas that the small bronzes were cast’.34 Moore’s catalogue raisonné also indicates that six of Moore’s preliminary terracotta maquettes were cast in bronze editions. This Maquette for Madonna and Child was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London. Notes made by Moore for the owner of the foundry, dated ‘March 28’, identify five Madonna and Child maquettes for casting, along with three maquettes for Moore’s Family Group, which date from 1944–5.35 The inclusion of Maquette for Family Group 1945 (Tate N05606) as the seventh sculpture on this list suggests that Moore made these casting notes in 1945. This Maquette for Madonna and Child is numbered one on the list, and a small sketch of the sculpture is annotated with the phrase ‘original for Northampton’. The notes indicate that five bronze casts were wanted and that three had been cast by 28 March. The sculpture exists in an edition of five plus one artist’s cast, although additional examples may have been cast. There is some uncertainty as to whether the unnumbered bronze maquettes were cast in editions of five or seven due to discrepancies between the foundry paperwork and Moore’s catalogue records held at the Henry Moore Foundation.36

In an article published in the Burlington Magazine in July 1948, David Sylvester, who had worked as Moore’s personal assistant in 1945, noted that ‘Moore had always made maquettes for his larger sculptures, but it was not until he cast about half-a-dozen of the ten or so clay studies for the Northampton Madonna that he began to make bronzes of them’.37 The bronzes were produced to be sold privately, and probably helped off-set the cost of the commission. Moore’s turn to making multiple bronze casts drastically altered the type of work he was able to produce, and provided more opportunities to sell his work.

Moore and the Tate collection

This maquette was one of four bronze studies for the Northampton Madonna and Child bought by Tate in 1945 and was thus one of the earliest works by Moore to be purchased for the Tate collection. The purchase of these works illustrated the desire of the director Sir John Rothenstein to represent Moore’s work in the collection. In contrast, Rothenstein’s predecessor, J.B. Manson, had previously told the Tate trustee Robert Sainsbury ‘over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate’.38 Rothenstein’s appointment thus signalled a shift in the direction of Tate’s ambitions. One of his first actions as director had been to accept the donation from the Contemporary Art Society of Moore’s Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387). Then in 1941 Rothenstein encouraged the appointment of Moore to Tate’s Board of Trustees.

In 1944 Rothenstein wrote to Moore asking whether Tate could commission another full-size Madonna and Child based on the existing maquettes. Moore politely turned down the suggestion, writing ‘its now more than a year since these little figure studies were done, + that’s whats [sic] making me hesitate now over your suggestion – for it would mean putting my mind back in working to a year ago’.39 Instead, Moore suggested that the Tate might be interested in some of the studies for a ‘Family Group’ he had recently begun working on. This proposal was accepted and Tate bought four maquettes for the Madonna and Child and three maquettes for the Family Group. Three of the Madonna and Child maquettes were bought at the relatively affordable price of twenty-five guineas each, while this maquette cost thirty guineas because it was the version from which the final full-size sculpture had been scaled up.40

The four maquettes for Madonna and Child were purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries in early 1945 with money from the Knapping Fund.41 The Knapping Fund was the residuary estate of Miss Helen Knapping bequeathed to the Trustees of the National Gallery in 1935 to be spent on work by living or recently deceased British artists. A fraction of this money was allocated to the Tate by the National Gallery, as Tate’s purchasing power continued to rely on charitable donations and private patronage until well after the Second World War.

All four of Tate’s Madonna and Child maquettes were exhibited in Moore’s solo exhibition at the British Pavilion at the 1948 Venice Biennale, at which Moore won the International Sculpture Prize, cementing his position as Britain’s ‘greatest living sculptor’.

Other examples of this sculpture can be found in the collections of the Northampton Museum and Art Gallery, Northampton; Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich; and the British Council, London.42 The original clay maquette is held in the collection of the Moore Danowski Trust.

Robert Sutton

December 2012

Revised by Alice Correia

March 2014

Notes

Walter Hussey, Patron of Art: The Revival of a Great Tradition Among Modern Artists, London 1985, p.23.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Carroll, The Donald Carroll Interviews, London 1973, p.35, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.269.

The pages from the sketchbook are reproduced in Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Drawings 1940–49, Aldershot 2001, pp.190–5.

See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Drawings 1940–49, Much Hadham 2001, p.193, no.43.96.

Moore photographed these terracotta maquettes in various groupings prior to their casting. Fig.4 illustrates six of the twelve models and were reproduced in Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculptures and Drawings, London 1944. This book would become the basis for the first volume of Moore’s catalogue raisonné, in which the same two photographs have been reproduced ever since. See David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, 5th edn, London 1988, p.138.

A.D.B. Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture: I’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.543, June 1948, p.158.

Henry Moore cited in Church of St Matthew, Northampton, 1893–1943, Northampton 1943, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.267.

Walter Hussey, ‘A Churchman Discusses Art in the Church’, Studio, vol.138, no.678, September 1949, p.80.

Anon., ‘Madonna Statue Causes a Sensation’, Northampton Independent, 25 February 1944, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Anon., ‘Madonna Statue – Experts’ Impressions’, Northampton Independent, 25 February 1944, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Geoffrey Grigson and Eric Newton, ‘Henry Moore’s Madonna and Child’, Architectural Review, vol.95, no.569, May 1944, p.139.

See John and Véra Russell, ‘Conversations with Henry Moore’, Sunday Times, 17 December 1961, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, pp.47, 230.

Henry Moore, ‘A Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.196.

Henry Moore, Head of the Virgin 1922–3 (The Henry Moore Foundation), http://catalogue.henry-moore.org:8080/emuseum/view/objects/asitem/search@/3/invno-asc?t:state:flow=fad5a4f3-134d-4bdf-972c-34b2a62810c0 , accessed 6 March 2014.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeny, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, p.183, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.54.

Margaret Garlake, ‘Moore’s Eclecticism: Difference, Aesthetic Identity and Community in the Architectural Commissions 1938–1958’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.174.

Henry Moore, letter to Martin Butlin, 22 January 1963, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23941.

See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Drawings 1940–49, Much Hadham 2001, p.195, no.43.105.

Sylvester 1988, pp.12–13. It was not until some years after the Second World War that Moore began to efficiently maintain his financial and business paperwork.

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture II’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1948, p.190.

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, revised edn, London 2003, p.183. Manson’s remark was cited by Sainsbury during an interview undertaken by Berthoud in May 1983.

See http://visualarts.britishcouncil.org/collection/search/9/0/object/45733/0 , accessed 7 March 2014.

Related essays

- Myriad Mediations: Henry Moore and his Works on Screen 1937–83 John Wyver

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

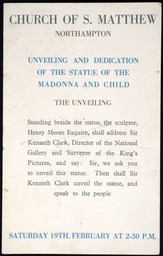

Programme for the unveiling and dedication of the statue ... 19 February 1944Programme

Related reviews and articles

- Philip Hendy, ‘Henry Moore: his New Exhibition’ Britain Today, no.158, June 1949.

Related bibliography

How to cite

Robert Sutton, ‘Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, revised by Alice Correia, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www