Henry Moore OM, CH Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Image 1 of 13

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Helmet Head No.1

1950, cast 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

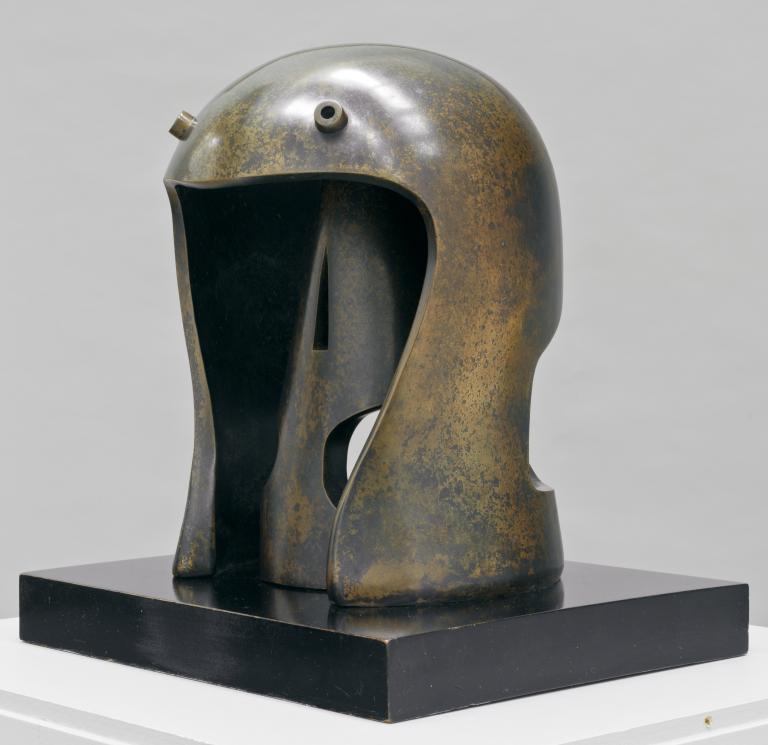

This bronze sculpture was cast in 1960 from a lead version originally made in 1950. It was the first in a series of works that addressed the theme of protection through the form of a militaristic helmet. Most critics have interpreted Helmet Head No.1 with reference to the Second World War, but it may also have been informed by Moore’s experiences of fighting in the trenches during the First World War.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Helmet Head No.1

1950, cast 1960

Bronze on wood base

400 x 355 x 300 mm

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

Number 2 in and edition of 9 plus 1 artist’s copy

T00388

Helmet Head No.1

1950, cast 1960

Bronze on wood base

400 x 355 x 300 mm

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

Number 2 in and edition of 9 plus 1 artist’s copy

T00388

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by the Friends of the Tate Gallery, by whom presented to Tate in 1960.

Exhibition history

1963

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston upon Hull, October–November 1963, no.4.

1964

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore at King’s Lynn, St Margaret’s Church, King’s Lynn, July–August 1964, no.15.

1972

Sculpture for the Blind, Tate Gallery, London, November–December 1976, no number.

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, September–November 1973, no.39.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977, no.51.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981–2

British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century. Part Two: Symbol and Imagination 1950–80, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1981–January 1982.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.208.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1989

Henry Moore, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny, May–November 1989, no number.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.62.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, May–September 2004, no.48.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.34.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no number.

2011

Camulodunum, First Sight, Colchester, September 2011–January 2012.

References

1951

Exhibition of New Bronzes and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1951, reproduced.

1953

Wonder and Horror of the Human Head, exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1953.

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, pp.99–103 (lead original reproduced pl.71).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.106–8 (lead original reproduced pl.94).

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962, reproduced p.3.

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, no.279 (lead original reproduced pl.10).

1967

Anton Ehrenzweig, The Hidden Order of Art: A Study in the Psychology of Artistic Imagination, London 1967, pp.212–13.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, New York 1968 (another cast reproduced pl.114).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.167 (?another cast reproduced pls.401–2).

1971

Oto Bihalji-Merin, Masks of the World, London 1971, pp.177–202.

1973

Henry Moore at Home: A Private View of a Personal Collection, television programme, broadcast BBC2, 8 January 1974, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8811.shtml, accessed 26 November 2013.

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1973, reproduced p.52.

1975

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1975, pp.138–42 (?another cast reproduced pl.68).

1977

Der Kopf: Plastiken aus dem 20.Jahrhunderts, exhibition catalogue, Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg 1977, pp.30–1.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977, reproduced pp.93, 165.

1978

80/80: To Celebrate Henry Moore’s 80th birthday on 30 July 1978, exhibition catalogue, Thomas Gibson Fine Art, London 1978 (another cast reproduced p.21).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.26.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981, reproduced p.108.

1982

Henry Moore: Head-Helmet, exhibition catalogue, DLI Museum and Arts Centre, Durham 1982, p.18.

1989

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny 1989 (lead cast reproduced pp.162–3).

1990

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Darkness in the Shelter’, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Bilbao 1990, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Bilbao.pdf, accessed 23 September 2013.

1993

Laura Doan, ‘Wombs of War: Henry Moore’s Repositioning of Gender’, Gender, no.17, fall 1993, pp.41–58.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, reproduced p.210.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, reproduced p.107.

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.64.

2006

Julian Andrews, ‘Helmet Head No.1’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.225–6 (another cast reproduced p.225).

2006

Henry Moore: War and Utility, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2006 (lead original reproduced on frontispiece and p.22).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (lead cast reproduced p.63).

2009

Paul Stirton, ‘British Artists and the Spanish Civil War’, in The Discovery of Spain: British Artists and Collectors, Goya to Picasso, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2009, pp.133–7.

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010 (lead original reproduced no.124).

2011

Michelle Cotton (ed.), Camulodunum, exhibition catalogue, First Sight, Colchester 2011, p.57.

Technique and condition

This small sculpture consists of a hollow, domed, helmet-shaped form and a vertical, separate conical form, both of which are cast in bronze. The conical component is positioned inside the helmet-shaped form. The sculpture is mounted on a square wooden base that has been painted black. The inner and outer forms have each been fixed to the base by threaded studs held in place by recessed bolts. Two studs have been used to attach the inner form and three have been used for the outer.

The original model for this sculpture was probably made in wax, which would then have been surrounded with a refractory material and heated, creating a hard mould from which the sculpture could be cast. Although this is technically a ‘lost wax’ process, it is often referred to as ‘direct casting’ because it involves the loss of the artist’s original model. Moore cast the initial lead version of this sculpture himself in 1950. The lead was probably then used to create a mould from which the bronze edition was cast at a foundry in 1960.

Tate’s version of Helmet Head No.1 was cast at the Fiorini and Carney foundry in London as part of an edition of nine plus one artist’s cast. There are small residues of casting investment trapped in crevices inside the sculpture, providing evidence that it was fabricated using the lost wax casting technique (fig.1). The sculpture would have been finished with abrasives after casting to give the bronze a reflective surface.

The bronze would then have been artificially patinated. This process involved applying chemical solutions to its surface that reacted with the bronze to produce coloured chemical compounds. In this case the patina is made up of several shades of brown, which could have been achieved by using a solution called potassium polysulphide (sometimes known as ‘liver of sulphur’). The reaction triggered by applying this solution to bronze is capable of producing a range of shades between brown and black, and this can be controlled by altering the temperature and concentration of the solution. These solutions would usually have been applied in one or more even layers using a brush. However Moore instead used an innovative technique to spray the solution directly onto the surface, giving the bronze a speckled appearance. The finish of the sculpture would have been secured by a coat of wax, which is used to saturate the colour and protect the surface.

This bronze has not been inscribed with the artist’s signature or a foundry mark.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', October 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

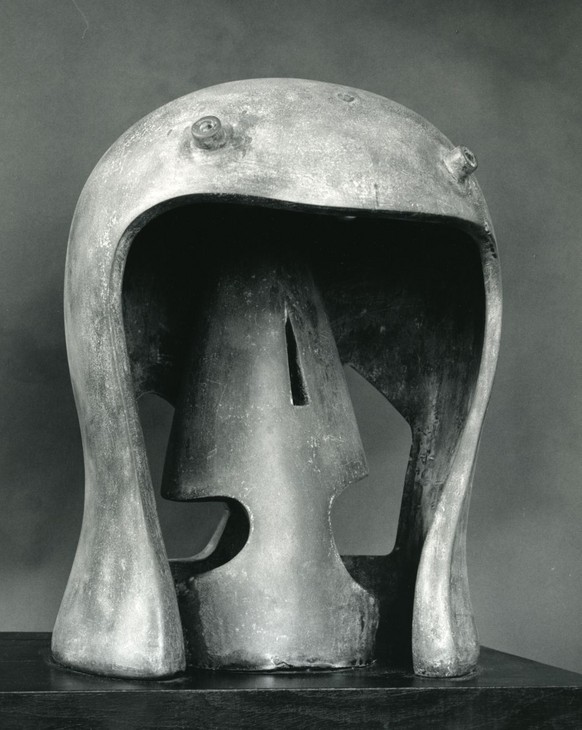

Helmet Head No.1 consists of a hollow, loosely cylindrical form capped by a shallow dome, inside which a conical form stands vertically on its circular base pointing up to the interior ceiling of the dome. Both elements are cast in bronze and are mounted separately on a wooden base.

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960, Rear view

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960, Rear view

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

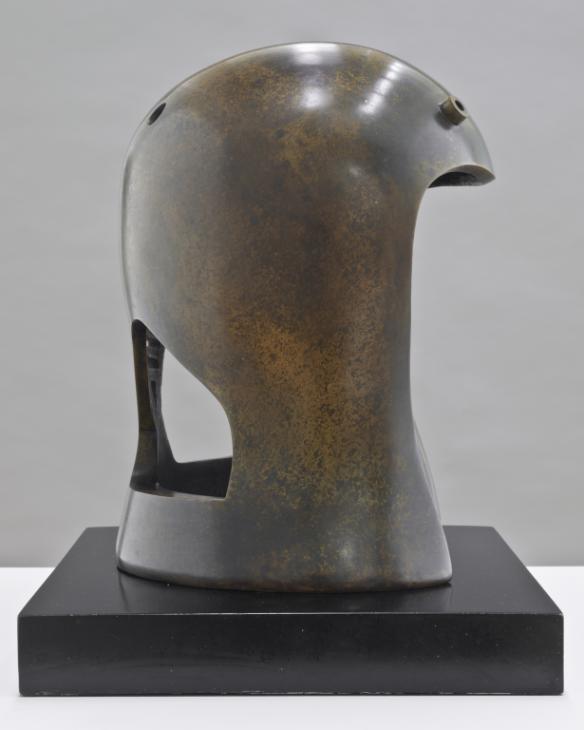

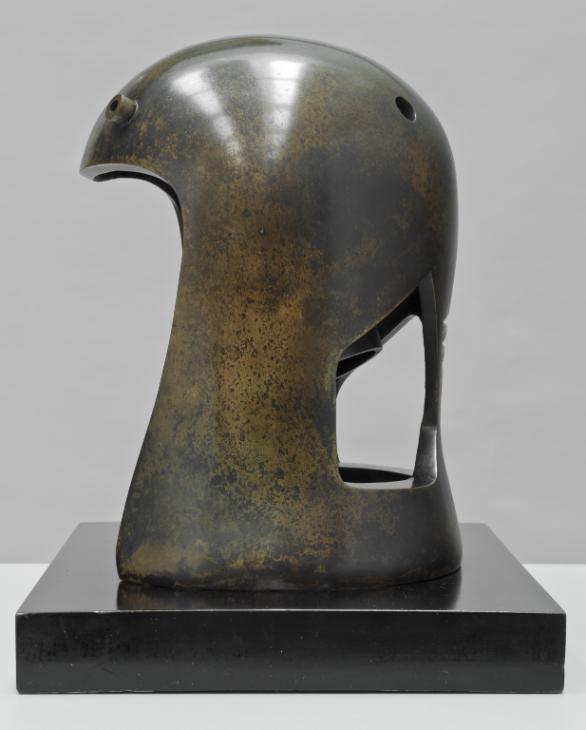

As the title implies, the shape of the outer form resembles a helmet, with a wide, loosely rectangular opening with curved corners at the front. This opening extends from the very bottom of the sculpture across a third of the circumference, up to approximately three-quarters of its height, terminating just below the curve of the dome at the top (fig.1). The sides of the helmet curve inwards slightly just above the base before curving outwards into the dome, while the back of the helmet extends continuously from the apex of the dome down to the base, but is punctured by two irregular shaped openings that have been cut through the surface at around the same point that the sides curve inwards (fig.2). These two five-sided openings, which are made of straight and curved edges, are the only irregular shapes in what is otherwise a symmetrical design. When viewed from the back, the opening on the right, which is the shorter and wider of the two, is in fact the same shape as the left-hand opening but rotated at ninety degrees. Cut into the surface of the central bridge separating these two openings is a pattern consisting of three horizontal, parallel lines positioned just above a triangle. Two small, tubular nodules appear on the upper surface of the helmet towards the front, while in the same position on the back of the helmet are two round holes.

Visible through each of the openings is the inner element of the sculpture. This upright conical form has also been cut into and features a horizontal void with rounded sides that traverses three quarters of the circumference just above the base, leaving only a thin strip of bronze at the front to bridge the upper half of the cone to its base. The interior of the cone can be seen through a combination of this rounded hole and the openings in the back of the helmet (fig.3). A triangle with steep sides has also been cut into the front surface of the conical form above the central strip of bronze (see fig.1). Examination of the helmet’s interior reveals that the conical form does not culminate in a sharp point but has been truncated in order to fit within the outer shell. It is also apparent that the interior and exterior pieces are not attached from the inside, and do not touch at any point.

Origins and fabrication

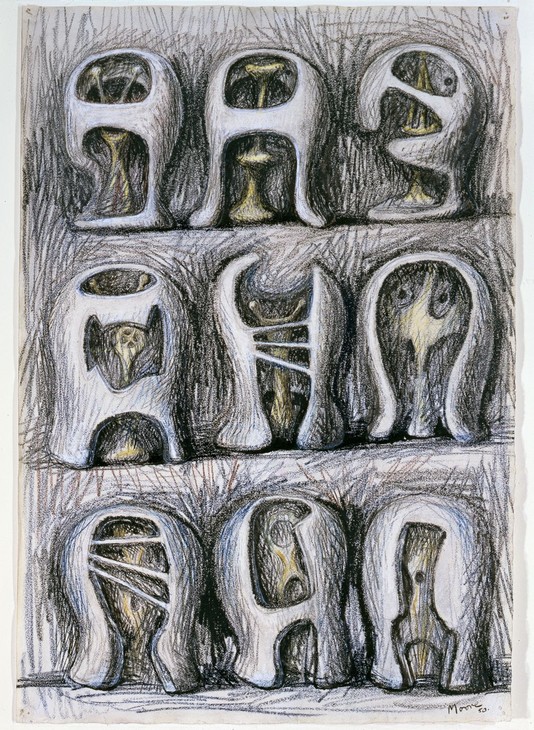

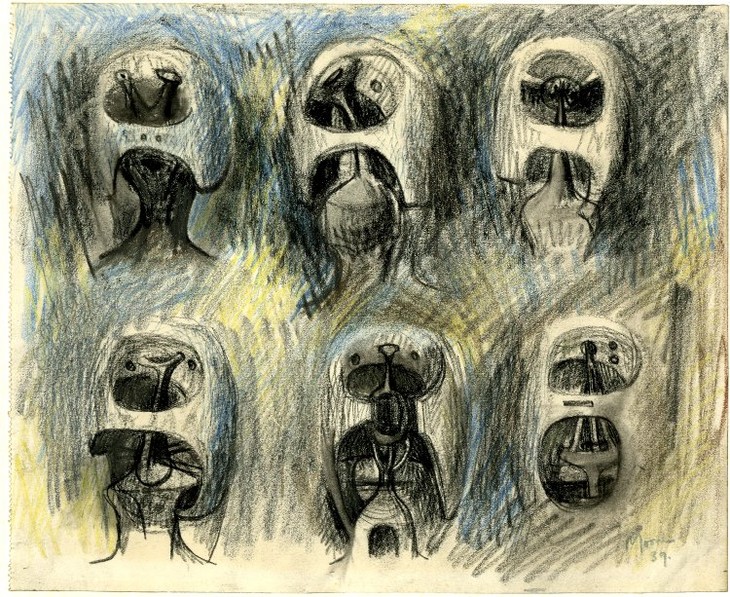

Henry Moore

Nine Helmet Heads 1948

Pencil, chalk and coloured crayon on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Nine Helmet Heads 1948

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

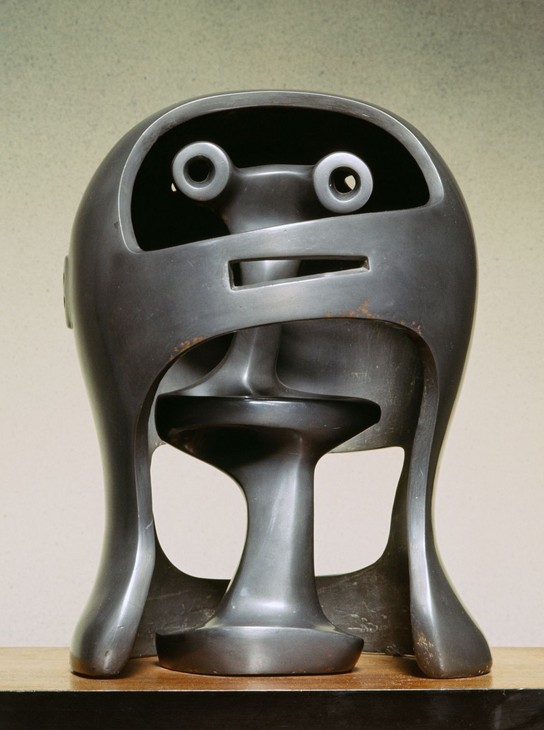

Henry Moore

Maquette for Helmet Head No.1 1950

Lead

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Maquette for Helmet Head No.1 1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

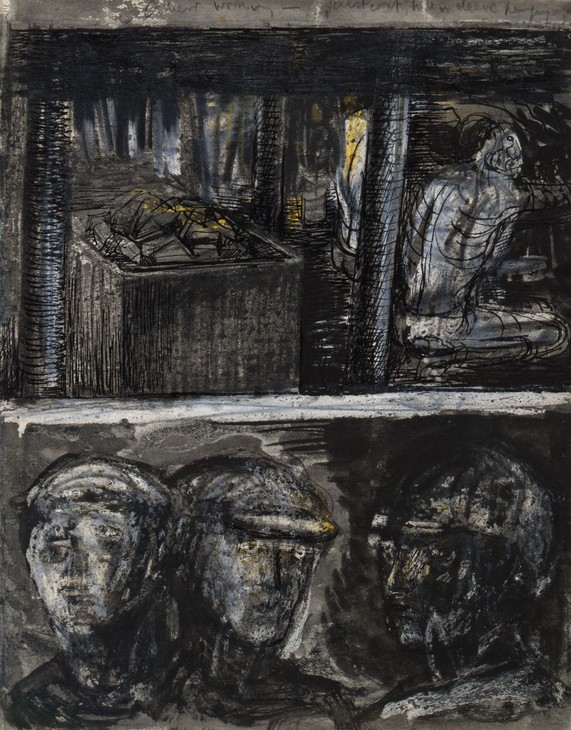

Moore made numerous ‘Helmet Head’ sculptures over the course of his career. The series can be traced to drawings made by Moore between 1948 and 1950, such as Nine Helmet Heads 1948 (fig.4). In this sketch Moore combined his ideas regarding outer protective structures and interior forms with his interest in helmets and armour. In 1980 Moore suggested that ‘the idea of one form inside another form may owe some of its incipient beginnings to my interest at one stage when I discovered armour. I spent many hours in the Wallace Collection, in London, looking at armour’.1 Visiting the Wallace Collection as a student in the 1920s, Moore would have had access to one of the largest collections of armoury in Britain, including items dating back to the fourteenth century.

In order to realise his pencil designs as a bronze sculpture, Moore would have first created a small three-dimensional model in a soft, malleable material such as wax. In 1987 Alan Ingham, who worked as Moore’s assistant between 1950 and 1953, recalled that much of Moore’s day ‘would be spent in the studio working on small wax maquettes’.2 Moore then made a lead cast from the wax model, titled Maquette for Helmet Head No.1 1950 (fig.5). This small sculpture served as a preparatory study, fabricated to test the composition in three dimensions and provide a sense of what the full-size version might look like.

Henry Moore

Five Figures: Interiors for Helmets 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Five Figures: Interiors for Helmets 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950

Lead

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although Moore claimed that the Hoglands foundry had been built for bronze casting it was also used for lead casting. Indeed, attempts to cast bronze, according to his friend and former assistant Bernard Meadows, ‘never really worked because the furnace didn’t get hot enough to melt the bronze!’5 Lead, on the other hand, has a much lower melting point than bronze, and the practice of ‘backyard casting’ in lead was relatively common among artists working on small scale sculptures.

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.2 1950

Lead

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.2 1950

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In April 1969 Moore wrote a lengthy letter to his dealer Harry Fischer of Marlborough Fine Art expressing his satisfaction at the sale of the lead Helmet Head No.2.7 In the letter Moore gave an extensive description of how this work was created, and it is probable that he used the same process to fabricate the lead version of Helmet Head No.1. Moore recorded that ‘to realise the form of this particular sculpture, with its thin outer shell, and its separate interior piece, I had to work in some material other then clay or plaster. I decided I would model direct in wax, (this would also mean I could later use the “cire-perdue” (lost wax) method of metal casting)’.8 In order to make the helmet section Moore:

made a solid shape [out of plaster mixed with grog] similar to the outside form of the HELMET, over this shape I modelled the exterior part of the HELMET, in wax, about one centimetre in thickness. I then covered this with an outer mould, (also a mixture of plaster and grog).

The whole was then baked in a brick kiln, during which the wax melts and is lost leaving nothing in its place, and into this empty space the molten lead was poured.9

The whole was then baked in a brick kiln, during which the wax melts and is lost leaving nothing in its place, and into this empty space the molten lead was poured.9

Moore recalled that the interior piece was made in a similar way. The shape was first modelled in wax, but without the inner core. It was then encased in the plaster and grog mixture, baked in the kiln and, after the melted wax had drained away, the empty space was filled with molten lead. When the lead had cooled and hardened, the outer casing would have been removed to reveal the sculpture inside. One of the disadvantages of working in wax and using this ‘direct’ method of casting was that the original sculpture was destroyed during the casting process, and so there was only one opportunity to cast the sculpture in metal. If a serious error occurred at any stage of the process, and a copy of the wax had not already been made, the sculpture would be lost. In his letter to Fischer, Moore went on to explain that, after being cast, both components of Helmet Head No.2 still required considerable work. He stated:

the exterior and the interior forms now existing in lead did not have the exactitude of shape and surface which I wanted, and I spent several days working directly on both parts of the sculpture with progressively finer grades of files – finally finishing with pumice powder and metal polish, and so arriving at a surface unique to lead – a kind of bloom entirely different from unpolished lead.10

A bronze edition of Helmet Head No.2 was cast in 1955, but the bronze edition of Helmet Head No.1 was not cast until 1960. It is unclear why Moore waited ten years between creating the lead version and casting it in bronze. In any case Moore did not attempt to cast the bronze himself but instead employed the Fiorini and Carney foundry in London to produce an edition on nine, plus one artist’s copy.11 Moore had previously commissioned Fiorini to cast his Family Group 1948–9 (Tate N06004) and, although the foundry had initially experienced problems casting large-scale works, Moore nonetheless continued to use them throughout the 1950s. Tate’s Falling Warrior 1956–7 (Tate T02278) was also cast by Fiorini and Carney.

Detail of casting investment in Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of casting investment in Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of interior surface of Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of interior surface of Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is likely that the bronze sculpture was also cast using the lost wax technique because traces of casting investment can be found in one of the circular holes made in the dome of the exterior piece (fig.9). This technique would have required the foundry to create moulds of the two components of Helmet Head No.1 using the original lead version, from which wax models could be produced. The casting process would have then followed the same procedures that Moore had used when he made the lead version.12 The art historian Julian Andrews has suggested that the two cylindrical nodules positioned on the front of the helmet ‘would originally have been sprues, small vents or channels through with surplus metal, wax and air were expelled from the casting mould’.13

After they had been cast the exterior surfaces of both components were smoothed and polished, leaving them slightly reflective although not shiny. A comparison of the interior and exterior surfaces of the dome (fig.10) suggests that the outside was finished with abrasives to achieve its smooth texture, whereas the interior surface did not receive further treatment. It is unclear whether this process was carried out at the foundry or by one of Moore’s assistants.

Once the bronze had been filed, Moore was then able to make decisions about the patina. A patina is an artificial surface colour, usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. In 1964 Moore asserted that ‘some sculptors leave the whole question of patinas to the bronze foundry. Not so myself. The addition of the patina is of great importance, and something which I must consider and evolve myself’.14 The patina of Tate’s Helmet Head No.1 is speckled, as though the chemical solution was applied to the bronze surface using a spray. Its colour is predominantly black and brown, although notable patches of the surface are deep orange. Although it is usually very difficult to replicate patinas across an edition, the example of Helmet Head No.1 in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York has a similar patina to the version belonging to Tate.15

Context and interpretation

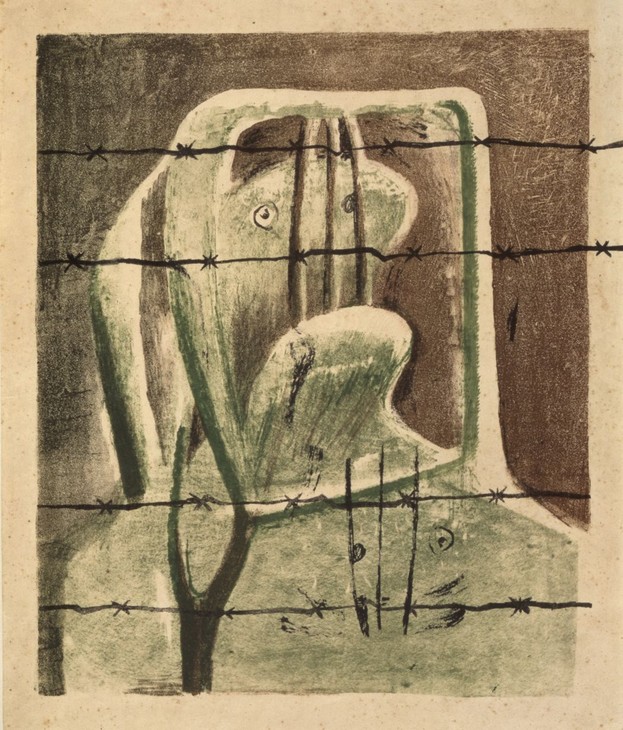

Henry Moore

Spanish Prisoner 1939

Lithograph on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Spanish Prisoner 1939

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939

Charcoal, wash, pen and ink on paper

277 x 381 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Heads 1939

Charcoal, crayon, chalk, pen and ink on paper

216 x 254 mm

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Heads 1939

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1939 Moore made a number of drawings depicting the helmet head motif. Later, in 1967, he explained that in developing his ‘Helmet Head’ series he was interested in ‘the mystery of semiobscurity where one can only half distinguish something. In the helmet you do not quite know what is inside’.17 According to art historian Andrew Causey, in Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939 (fig.12) ‘Moore’s hatching and shading create dark corners and uncomfortable spaces’ that convey the widespread anxiety felt within society regarding the impending Second World War.18 In 1968 the critic John Russell traced the origins of the ‘Helmet Head’ series to a particular watercolour and chalk drawing from 1939 (fig.13), writing:

Moore had conceived of a small sculpture which would be both head and helmet, armour and living organism, internal and external form. Thus described, it might seem to have timely martial associations, but in point of fact the implications of the Helmet pieces are a good deal more complex. It is uncertain, for instance, whether the internal figure is protected or imprisoned by the helmet itself: whether it has, in short, got into a situation which it can no longer control. From the way in which this idea went on battering for Moore’s attention until well into the 1960s we can assume that it has a particular significance for him.19

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Lead

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

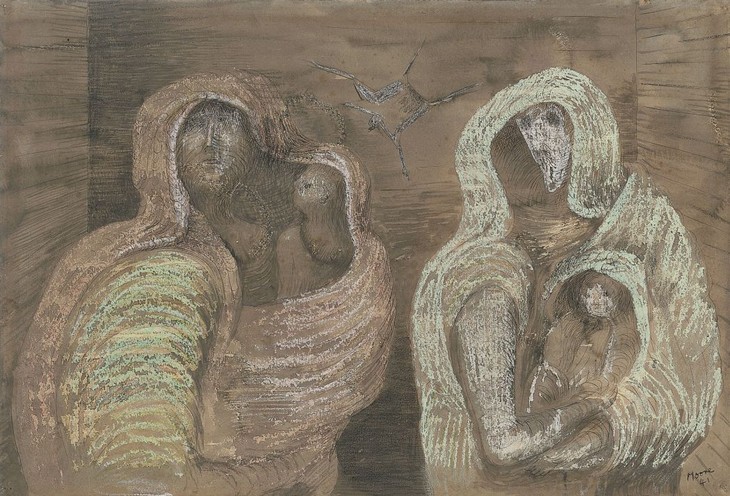

Henry Moore

Two Mothers Holding Children 1941

Pen, ink, wax crayon and watercolour on paper

380 x 564 mm

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Two Mothers Holding Children 1941

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s first sculpture to take the form of a helmet and combine interior and exterior forms was The Helmet 1939–40 (fig.14). This lead sculpture was also one of the last three-dimensional works produced by Moore before a lack of available resources halted his sculptural practice in 1940.20 For this work Moore enclosed a vertical form made up of arches and ellipses, evocative of a standing figure within a domed shelter. The art historian Julian Stallabrass has argued that Moore’s sculptures utilising the helmet form ‘have a very definite relation to the war’, and it is true that Moore continued to explore the formal relationship between interior figures and enclosing shells in his ‘Shelter Drawings’ of 1940–1, which depict groups of people sheltering in the London Underground during air raids.21 In works such as Two Mothers Holding Children 1941 (fig.15), for example, blankets follow the curvature of the bodies beneath and create apparently rigid domed helmets over the figures’ heads, recalling the form of The Helmet and anticipating the form taken by the outer component of Helmet Head No.1. These drawings also illustrate the relationship between Moore’s helmet heads and his interest in the mother and child motif. In 1967 Moore acknowledged that the compositional arrangement of The Helmet related to ‘the Mother and Child where the outer form, the mother, is protecting the inner form, the child’.22 Furthermore, the German psychologist Erich Neumann argued in 1959 that The Helmet is ‘dominated by the mother-child symbolism: it forms a uterine shell within which there dwells a child inhabitant’.23

Henry Moore

Openwork Head and Shoulders 1950

Bronze

455 x 390 x 260 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Openwork Head and Shoulders 1950

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

only as a mask, a hollow shell derived from the outer layer of skin and muscle. These heads have been, so to speak, peeled off the bone, the density and solidity of the head’s structure are broken down, and all that remains is the outline of the form, with nothing inside save the air filtering in through the openwork.26

Neumann concluded that Moore’s experimentation with latticed, open, figurative structures ‘has resulted in a representation of the “nihilistic” man of today, obsessed with the Void, le néant, nothingness’.27 Grohmann similarly asserted that in the 1950s the interior figure of the ‘Helmet Heads’ changed from a recognisable human figure ‘into a more compact shape, that has something repellent, technological and warlike about it that is not unlike a stereo-telescope’.28 He continued:

during the air attacks on London, Moore’s thoughts must have circled round life and death that subsequently led to compositions such as these. The helmet and internal shapes of 1950 are, in any case, frightening, combative, as compositions not far removed from representations of death.29

In spite of the role he attributed to the Second World War in prompting Moore’s return to the helmet motif, Grohmann warned against interpreting it as an all-encompassing explanation of the series, arguing that ‘the possibility that steel helmets and gas masks, the paraphernalia of war and defence, played a motivating role cannot be dismissed out of hand, but in Moore’s case this factor can only have served as a confirmation of his inner ideas’.30

It is evident, then, that Moore was thinking about the representation of humanity in a number of different ways when he created Helmet Head No.1 in 1950. Indeed, in 1990 Julian Stallabrass recognised that in their indebtedness to the formal character of armoury and their mechanised representation of the human body, ‘the Helmet Heads and many of the associated pieces do not fit in comfortably with the rest of Moore’s work’.31 Stallabrass asserted that the militaristic connotations of the ‘Helmet Heads’ seemed at odds with the female, organic, and humanistic character of much of Moore’s work. However, according to Stallabrass, ‘our comfortable view of the works of Moore is a comparatively recent phenomenon. In the post-war period his work was seen at least with a large measure of unease and at the extreme with disgust and repugnance’.32

Henry Moore

Superior Eye 1974–5, from Helmet Head Lithographs 1974–5

Lithograph on paper

311 x 318 mm

Tate P02266

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Superior Eye 1974–5, from Helmet Head Lithographs 1974–5

Tate P02266

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Perhaps building on Moore’s statement regarding his 1975 lithographs, in 2006 Julian Andrews suggested that, rather than the military apparatuses of the Second World War,

far more likely as an influence, surely, is the sculptor’s own direct experience of confrontation with helmets during the German counter-attack at Bourlon Wood Cambrai, on 30 November 1917, when the nineteen-year-old Moore was serving with the 15th battalion of the 47th (London) Division, the Civil Service Rifles. Helmet Head No.1 does, in fact, bear strong similarities to the classic German ‘coalscuttle’ helmet – Stahlhelm M16 [fig.18].34

Andrews goes on to suggest that the two nodules on the top of the helmet are ‘precisely the same size and shape as the lugs on each side of the M16 helmet, originally intended to hold a protective steel plate for use by snipers’.35

In 1993 the historian Laura Doan published an article titled ‘Wombs of War: Henry Moore’s Repositioning of Gender’, in which she examined Helmet Head No.1 in light of the sexual politics of the post-war era. For Doan, The Helmet 1939–40 is an example of an archetypal vision of woman as a figure of protection and, like Neumann, she asserted that the interior (male) figure is held in safety within the womb-like space. However, rather than identifying the outer component of Helmet Head No.1 as delineating a similarly protective, nurturing space, Doan saw the nodules on its upper surface as:

reminiscent of fallopian tubes, but their truncated, cauterized, and atrophied appearance suggests an inability to create new life and assaults not true but denatured mother. Such barrenness represents the rejection of motherhood by those women of child-bearing age who persist in working outside the home – an all too real possibility, for there seemed to be no guarantee that they could be coerced from the jobs they held during the war.36

In this interpretation, the interior conical form of Helmet Head No.1 is read as a non-figurative phallic spear that pierces the interior space, whereby ‘the spear’s upward thrust and rigidity suggest ... a reassertion of masculinity’.37 As such, Doan asserts that in Helmet Head No.1 Moore offers:

a shattering representation of the masculine expedition/insertion into the female body. If the womb smothers the spear, given the danger and precariousness of violent penetration, this is at the womb’s, and therefore the woman’s own peril. Helmet Head No.1 depicts the ultimate forcible entry: rape in all its horror. Rape thus becomes not a dangerous threat from and result of war itself but a strategic, effective, and necessary means of masculine control over women’s bodies.38

Doan suggested that Moore’s sculpture registers a widespread post-war anxiety over women’s perceived refusal to conform to pre-war expectations of femininity. Having demonstrated their resilience in the absence of husbands and fathers and experienced the freedoms of the workplace, Doan noted that in the immediate post-war period a political rhetoric was established that sought to re-domesticate women and prioritise the normative family unit, which was later expressed in Moore’s Family Group 1949 (Tate N06004). The aim of this rhetoric, Doan argued, was to reconstruct a social order in which men dominated and controlled not only the economic and socio-political spheres, but also the bodies of women.

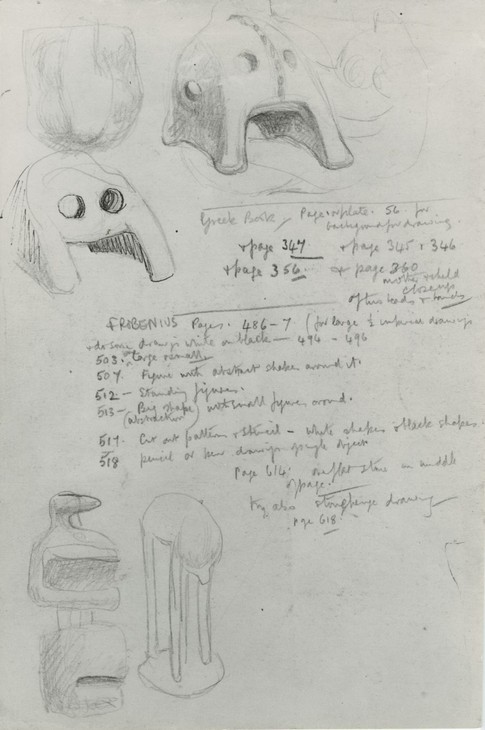

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture and Artist's Notes 1937

Graphite, pen and ink and chalk on paper

272 x 184 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture and Artist's Notes 1937

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Horse and rider ('Armento Rider') c.560–550 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.20

Horse and rider ('Armento Rider') c.560–550 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

In addition to the armoury Moore had seen in the Wallace Collection, the curator Alan Wilkinson has suggested that the external helmet shape and the holes cut out of its surface may have evolved from Moore’s study of ancient Greek artefacts. In 1937 Moore had copied two ancient helmet-like artefacts from reproductions illustrated in the critic Christian Zervos’s book L’art en Grèce des temps préhistorique au début du XVIIIe siècle published in 1934 (fig.19). Although the original function of these implements is unclear, Wilkinson asserted that ‘their shape may well have led to Moore’s drawings for helmet heads of 1939’.39 Following on from this proposal, Wilkinson concluded that ‘the drawings of the Greek works are, therefore, among the few copies which were to have a direct influence on Moore’s sculpture’.40

In addition to studying Zervos’s book Moore was familiar with the collection of ancient Greek statuary housed in the British Museum. In 1981 he selected a statue of an armed rider for publication in the book Henry Moore at the British Museum, in which items from the museum’s collection that had influenced him during his career were collated. The sculpture, known as the ‘Armento Rider’ (fig.20), depicts a male warrior wearing a Corinthian-style helmet and short tunic, seated upon a horse. Although Moore’s text makes no specific link between his ‘Helmet Head’ series and the ‘Armento Rider’, and the statue should not be regarded as a direct source, it is possible to see formal affinities between the helmet worn by the rider and the design of Helmet Head No.1.

In 2006 Roger Tolson, Head of the Art Department at the Imperial War Museum, London, identified a relationship between Helmet Head No.1 and Moore’s wartime series of drawings depicting the underground workings of Yorkshire’s collieries (fig.21). In these drawings, Tolson declared:

there is little evidence of the external world ... it is the miner-type figure that is seen in work such as Helmet Head No.1 and Upright Internal/External Form [Tate T02272], where a fluid and dynamic inner figure is constrained within an outer shell. These works carry ambiguous messages of threat and engagement, of external hostility and defence, of internal entrapment and protection.41

For Tolson the explicitly mechanical internal component of Helmet Head No.1 suggests that in this work Moore was addressing such questions as ‘who is master of the machine? Who directs its path and purpose? Can the individual survive outside of this engineered shell?’42

Acquisition and exhibition

Tate held thirteen sculptures by Henry Moore in its collection prior to the acquisition of Helmet Head No.1 in 1960. Since a large number of these were small maquettes, by the late 1950s the Trustees of the Tate were keen to expand the gallery’s holdings of Moore’s work. Acquisitions of Moore’s work had been hindered since the 1930s, first by J.B. Manson, Tate’s director between 1930 and 1938, who disliked modern art and who told Tate trustee Robert Sainsbury ‘Over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate’,43 and then by Moore’s subsequent post as a trustee of the gallery from 1941–8 and then 1949–56.44

After stepping down from his role as a trustee, Moore discussed a number of sculptures that could be made available to Tate with the gallery’s then director, Sir John Rothenstein. Moore proposed a list of eight works, which was presented to the trustees at their meeting on 16 May 1957.45 Although this proposed purchase did not occur immediately, the list, which included an example of each of Moore’s different subjects and materials to date, became the blueprint used by the Friends of the Tate for their acquisition of six sculptures by Moore in 1960. A letter to Moore dated 1961 from Jane Lascelles, Organising Secretary for the Friends, notes that there was no correspondence about the acquisition of these sculptures in the Friends’ files, suggesting that the particulars of the sale, including prices, were agreed verbally with Moore.46 In addition to Helmet Head No.1, the other sculptures presented to the gallery in December 1960 were Composition 1932 (Tate T00385), Stringed Figure 1938, cast 1960 (Tate T00386), Reclining Figure 1939 (Tate T00387), Mother and Child 1953 (Tate T00389), and Working Model for Unesco Reclining Figure 1957 (Tate T00390).

In 1976 Helmet Head No.1 was included in the exhibition Sculpture for the Blind, in which twelve sculptures from Tate’s permanent collection were exhibited for the blind and partially sighted, who were encouraged to experience the works through touch. In a review of the exhibition, critic Harold Osborne determined that ‘the Tate Gallery has shown commendable imagination and initiative in staging this exhibition’, and letters held in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive reveal that blind audiences were appreciative of the opportunity to experience Moore’s sculptures through touch.47 In 1978 Mary Ellis wrote to Moore and relayed her experience of being a gallery guide during the exhibition. In her letter she described how a schoolgirl, aged sixteen, had responded to Helmet Head No.1:

I told her it was very strange and there was something inside but I did not know what it was. She explored the inside for a long time and it was very moving to watch [her] sullen face at last beginning to soften. She said ‘I know – I know’. What she found remains her secret and perhaps yours.

Terry Measham [Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery] said you had specially wanted the Helmet Head to be included and if it had only been for that one blind youngster it would have been enough, but it fascinated nearly all our blind visitors.48

Terry Measham [Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery] said you had specially wanted the Helmet Head to be included and if it had only been for that one blind youngster it would have been enough, but it fascinated nearly all our blind visitors.48

Helmet Head No.1 was also included in Moore’s eightieth birthday exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1978 (fig.27), where it was installed alongside Reclining Figure 1951 (Tate T02270) and Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 (Tate T02272). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.49 Since then Helmet Head No.1 has been on regular display as part of the gallery’s permanent collection.

The original lead version of Helmet Head No.1 is housed in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation. Tate’s bronze version is number two in the edition of nine, with other examples held at the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA).

Alice Correia

November 2013

Notes

Henry Moore in conversation with David Mitchinson, 1980, printed in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.213.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.232.

Henry Moore, letter to Martin Butlin, 13 April 1961, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23942.

For more information on Fiorini and Carney see http://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/british-bronze-founders-and-plaster-figure-makers-1800-1980-1/british-bronze-founders-and-plaster-figure-makers-1800-1980-f.php , accessed 25 October 2013.

For an explanatory video on lost wax casting see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/sculpture-techniques/ , accessed 17 October 2013.

Julian Andrews, ‘Helmet Head No.1’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.226.

Henry Moore cited in Mervyn Levy, ‘Henry Moore: Sculpture Against the Sky’, Studio International, May 1964, p.179, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.236.

For an image of this sculpture see http://www.moma.org/collection//browse_results.php?object_id=81223 , accessed 22 October 2013.

Henry Moore cited in Michael Chase, ‘Moore on his Methods’, Christian Science Monitor, 24 March 1967, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.214.

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Darkness in the Shelter’, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Bilbao 1990, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Bilbao.pdf , accessed 22 October 2013.

Ian Dejardin, ‘Square Forms and Heads’, Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, pp.97–8.

Alan Wilkinson, The Drawings of Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1977, p.144.

Roger Tolson, ‘Moore and the Machinery of War’, Henry Moore: War and Utility, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2006, p.31.

Minutes of Meeting of the Trustees of the Tate Gallery, 16 May 1957, Tate Public Records TG/4/2/742/2.

Related essays

- Life Forms: Henry Moore, Morphology and Biologism in the Interwar Years Edward Juler

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, November 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www