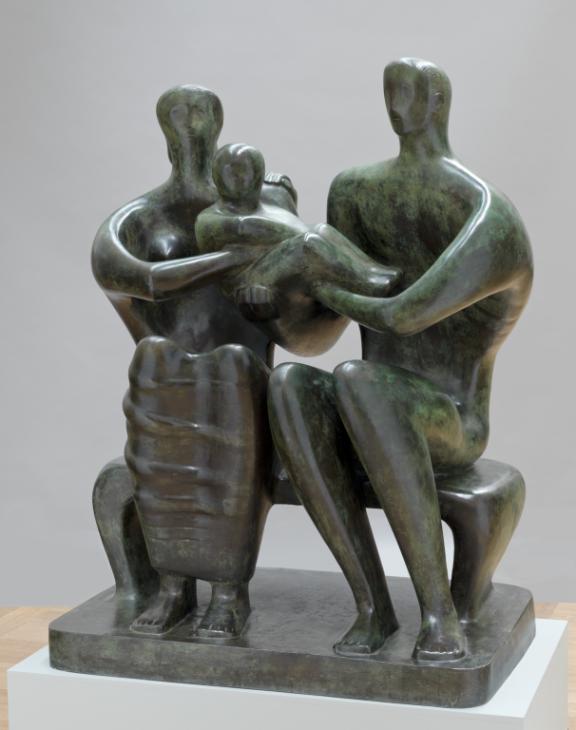

Henry Moore OM, CH Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1

Image 1 of 16

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Family Group 1949, cast 1950-1© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Family Group

1949, cast 1950-1

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Family Group was Moore’s first larger scale bronze sculpture. Originally designed for a school in Stevenage, the piece has been seen as symbolising aspects of the values of the post-war era of austerity and reconstruction.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Family Group

1949, cast 1950–1

Bronze

1540 x 1180 x 700 mm

Inscribed ‘Henry Moore’ and stamped ‘Alexis Rudier Fondeur, Paris’ on rear of base

Purchased from the artist through the Buchholz Gallery, New York (Grant-in-Aid) 1950

In an edition of 4 plus 2 artist’s copies

N06004

Family Group

1949, cast 1950–1

Bronze

1540 x 1180 x 700 mm

Inscribed ‘Henry Moore’ and stamped ‘Alexis Rudier Fondeur, Paris’ on rear of base

Purchased from the artist through the Buchholz Gallery, New York (Grant-in-Aid) 1950

In an edition of 4 plus 2 artist’s copies

N06004

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through the Buchholz Gallery, New York (Grant-in-Aid) 1950.

Exhibition history

1951

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, May–July 1951, no.169.

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.69.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.166.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.143.

1982–3

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, November 1982–January 1983, no.118.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, dibujos, grabados – obras de 1921 a 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas, March 1983, no.76.

1986

Das Bild der Frau in der Plastik des 20.Jahrhunderts, Wilhelm-Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, May–June 1986.

1998

Special Exhibitions: Henry Moore, Imperial War Museum, London, September–November 1998.

2001–2

Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, February–May 2001; Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June–September 2001; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., October 2001–January 2002, no.52.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, May–September 2004, no.20.

2006–7

Henry Moore: War and Utility, Imperial War Museum, London, September 2006–February 2007.

2012

Patrick Keiller: The Robinson Institute, Tate Britain, London, March–October 2012, no number.

References

1948

Rudolf Arnheim, ‘The Holes of Henry Moore: On the Function of Space in Sculpture’, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.7, no.1, September 1948, pp.29–38 (maquette reproduced p.34).

1951

Kenneth Clark, ‘Henry Moore’s Metal Sculpture’, Magazine of Art, vol.43, May 1951, pp.172–3 (another cast reproduced).

1951

David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, detail reproduced pl.14 (original plaster reproduced pl.15).

1955

George Wingfield Digby, Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists: Henry Moore, Edvard Munch, Paul Nash, London 1955, p.84.

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, pp.86–9 (plaster reproduced pl.54).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.142 (another cast reproduced pls.124–5).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, pp.157–65 (?another cast reproduced p.161).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.162–3, 176–7.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, reproduced p.103.

1968

Ionel Jianou, Henry Moore, Paris 1968 (another cast reproduced no.16).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.167 (?another cast reproduced pls.390–1).

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972, (?another cast reproduced p.141).

1973

Harry Rée, Educator Extraordinary: The Life and Achievement of Henry Morris 1889–1961, London 1973, p.72.

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977 (other casts reproduced pp.258–63, 338–41).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.25.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981, reproduced p.102, pls.193–4.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas 1983, reproduced p.99.

1986

Das Bild der Frau in der Plastik des 20.Jahrhunderts, exhibition catalogue, Wilhelm-Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg 1986.

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.224 (another cast reproduced p.86).

1989

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny 1989 (another cast reproduced pp.154–7).

1991

Art of the Forties, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1991, pp.138–9.

1993

Peter Fuller, Henry Moore: An Interpretation, London 1993, p.42 (another cast reproduced pl.5a).

1996

Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, pp.112–13.

2000

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art and the Post-Columbian World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2000 (another cast reproduced p.124, 127).

2001

Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, reproduced p.183, no.52.

2002

Henry Moore: Rétrospective, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul 2002 (another cast reproduced p.127).

2003

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, revised edn, London 2003, pp.259–63 (?another cast reproduced p.260).

2003

Margaret Garlake, ‘Moore’s Eclecticism: Difference, Aesthetic Identity and Community in the Architectural Commissions 1938–1958’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.173–93 (?another cast reproduced p.180).

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, pp.57–65, reproduced p.65, no.20.

2006

Henry Moore: War and Utility, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2006, reproduced p.56, no.27.

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006 (another cast reproduced p.130).

2006

Penelope Curtis, ‘Family Group 1948–49’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.220–1.

2006

Anthony Caro, ‘Family Group 1948–49’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.221–2.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (another cast reproduced p.54).

2013

Pauline Rose, Henry Moore in America: Art, Business and the Special Relationship, London 2013 (another cast reproduced on front cover).

Technique and condition

Henry Moore

Maquette for Family Group 1945

Terracotta

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Family Group 1945

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

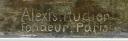

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

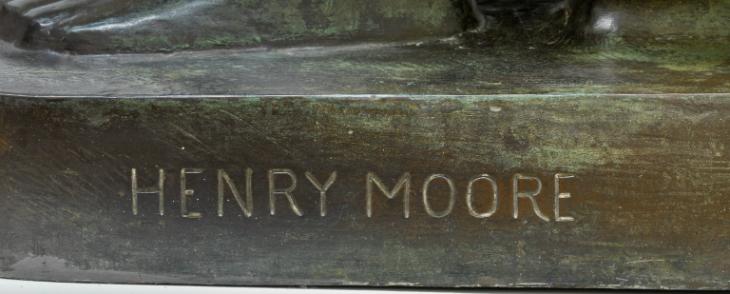

Detail of artist's signature on base of Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of artist's signature on base of Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is likely that the plaster model sent to the foundry was cut up into parts so that separate moulds could be created. The individual parts could then be pieced together after casting. Family Group was Moore’s first large sculpture to be cast in bronze, and was ultimately cast in an edition of four plus two artist’s copies. Tate’s Family Group was cast at the Rudier foundry in Paris between 1950 and 1951 and is likely to be number two or three in the edition. However, there is no edition number on the sculpture because by the time it was cast Moore had still not decided how many bronzes he would make. The sculpture is inscribed with the foundry name ‘Alexis.Rudier | Fondeur.Paris’ on the back of the base behind the woman (fig.2). (Although the founder Alexis Rudier died in 1897, the foundry continued to use his name until 1952.) The artist’s signature, ‘HENRY MOORE’, was inscribed into the side of the base next to the man’s left foot (fig.3).

The sculpture was cast in at least ten parts using the sand casting technique. The individual parts have been pieced together by roman joins, whereby a sleeved part is slotted into another part of the bronze and the two are secured by pins. The line and round pin of a roman join can be seen on the man’s left arm (fig.4). Other seam lines are discernible on the waists of both figures, on the legs of the man, and on the bench. The seam lines on the outside of the sculpture were finished by chasing a thin bronze flange with steel punches to render them practically invisible.

Detail of roman join on Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of roman join on Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

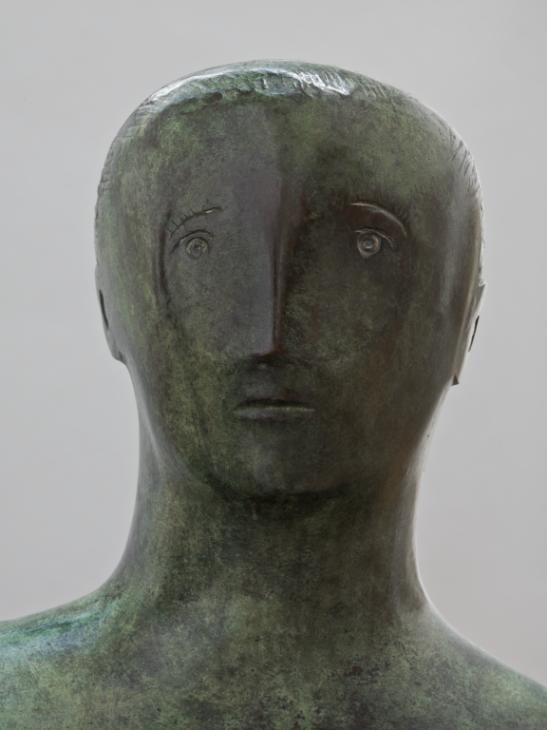

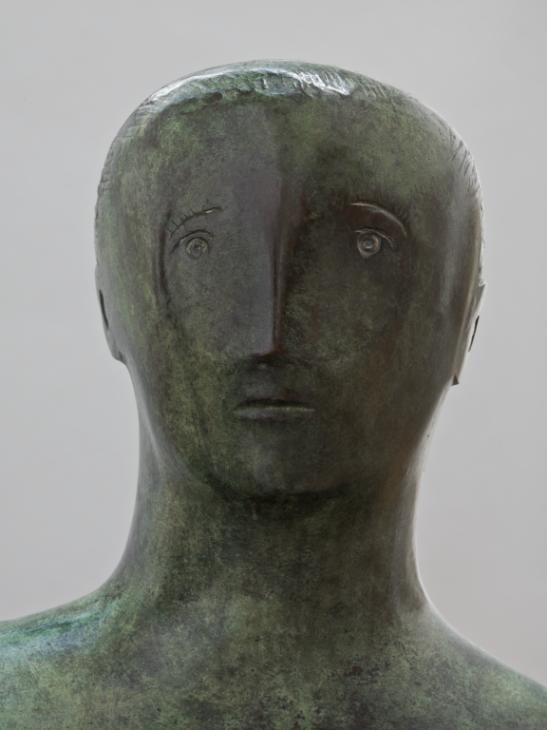

Henry Moore

Detail of man's face in Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Detail of man's face in Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The outside surfaces of the sculpture are very smooth, suggesting they were sanded after casting. The features of the faces and hair were carved into the original model but they were also sharpened after casting using thin punches (fig.5). The bronze surface was coloured using chemical patination techniques. First, a brown base layer was applied, followed by a green colour. The patination was probably carried out by Moore or one of his studio assistants.

Rozmarijn van der Molen

March 2014

How to cite

Rozmarijn van der Molen, 'Technique and Condition', March 2014, in Alice Correia, ‘Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

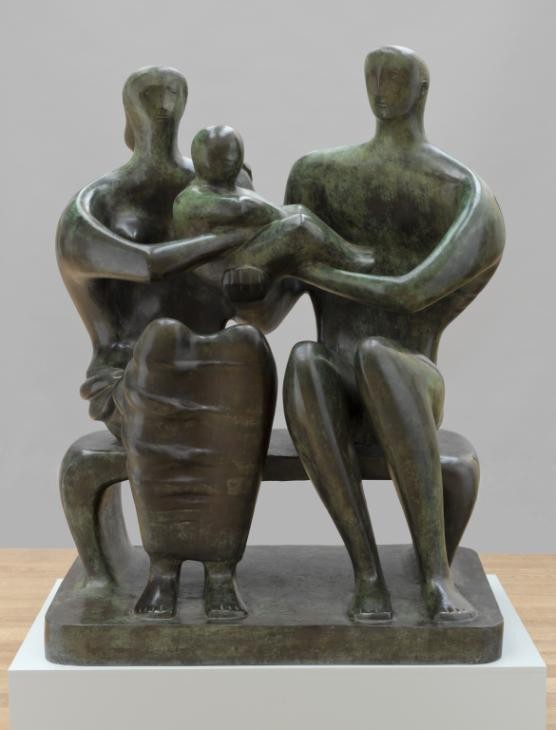

This bronze sculpture depicts an almost life-size man and woman seated on a low bench, holding a child between them. The woman sits to the right of the man and holds the child over her lap with both her arms. The man’s left arm support’s the child’s legs while his right hand rests on the woman’s left shoulder. The title, Family Group, indicates that the man and the woman are the parents of the small child.

Henry Moore

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1, Side view

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1, Side view

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The poses of the two adults seem to mirror each other, especially in the way that the woman’s right arm and the man’s left arm both curve outwards in a similar arc to hold the child between them (fig.1). The woman has small domed breasts and wears an ankle length skirt that drapes between her knees and stretches across the gap between her shins. Her legs are positioned straight in front of her, while the man’s thin, tubular legs are positioned at a slight angle, orientated towards the woman. Unlike the woman, the man does not appear to be wearing any clothing on his lower body.

When viewed from the side it becomes apparent that the sculpture is not very deep (fig.2). The figures’ knees are drawn up so that their bodies appear to be folding inwards, and their torsos are unnaturally thin. In contrast, the child is chubby and rounded. Positioned in the middle of the sculpture and held aloft by its parents, the child is the natural focal point. Discussing the arrangement of the figures, Moore identified how ‘the arms of the mother and the father [intertwine] with the child forming a knot between them, tying the three into a family unity’.1

Origins of Family Group

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Study for Mother and Child sculpture 1934–5

Graphite on paper

197 x 178 mm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Study for Mother and Child sculpture 1934–5

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

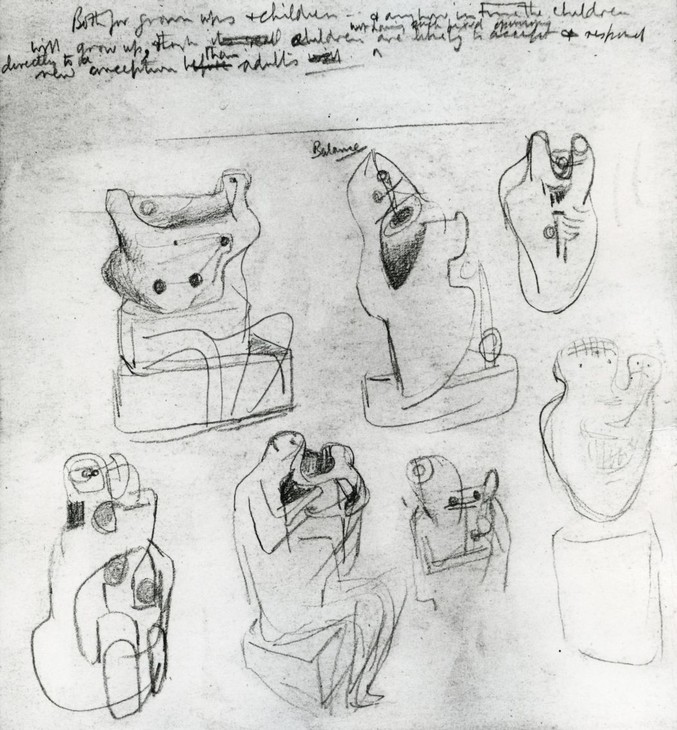

The college, which was opened in 1939, was designed to be a flexible space that catered for all the family, acting as the focal point for the entire community.4 Moore later recalled discussing the commission with Henry Morris, Chief Education Officer for Cambridgeshire County Council:

we talked and discussed it, and I think from that time dates my idea for the family as a subject for sculpture. Instead of just building a school, he was going to make a centre for the whole life of the surrounding villages, and we hit upon this idea of the family being the unit that we were aiming at.5

In 1951 Moore wrote that,

later the war came and I heard no more about it until, about 1944, Henry Morris told me that he now thought he could get enough money together for the sculpture if I would still like to think of doing it. I said yes, because the idea right from the start had appealed to me and I began drawings in note book form of family groups. From these note book drawings I made a number of small maquettes, a dozen or more.6

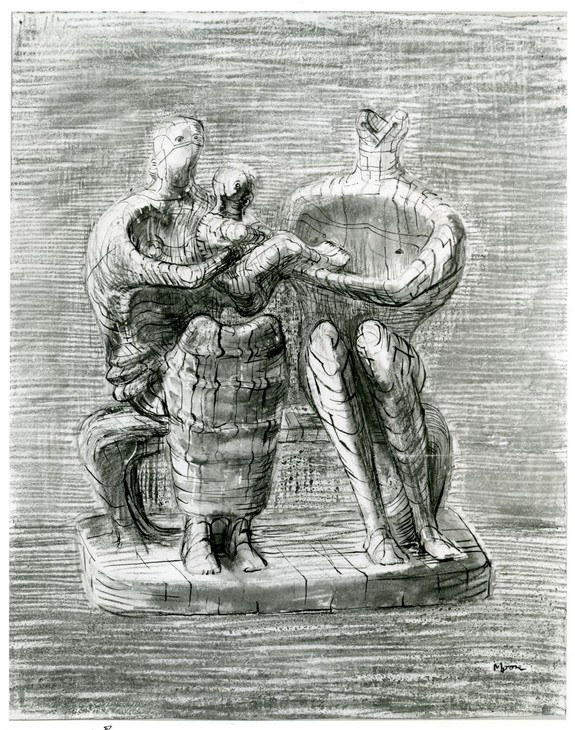

Henry Moore

Family Group 1945

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

490 x 390 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Family Group 1945

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Family Group 1945

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Family Group 1945

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Ultimately, the Impington commission was unsuccessful, as Moore recalled in 1951:

I must have worked for nine months or so on the Family Group themes and ideas, but again, Henry Morris found it difficult to raise money for the sculpture, and also my maquettes were not liked by the local Education authorities, and again nothing materialised. I carried out three or four of the six inch maquettes more fully in a slightly larger size for my own satisfaction, and then I went on with other work.11

However, an opportunity to complete the sculpture arose in 1947 when Moore was approached by John Newsom, the Director of Education in Hertfordshire, who enquired whether he would be interested in producing a new piece of sculpture for Barclay Secondary School, a new school in Stevenage. Moore readily agreed, ‘for here was the chance of carrying through one of the ideas on a large scale which I had wanted to do. I went to see the school and chose from my previous ideas the one which I thought would be right for Stevenage and also one which I had wanted most to carry out on a life-size scale’.12

Although it was not easy convincing the county education committee that the sculpture would be suitable, the commission was ultimately approved in 1949.13 The finished work was Moore’s first major bronze sculpture and his first large-scale sculpture to be editioned in multiple casts. According to Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud, ‘Henry’s fee had struck the education committee as excessive. So he reduced it to what he reckoned was cast price, about £750, covering casting, transport, materials, enlargement etc., on the understanding that he could make extra casts and dispose of them himself: a concession from which he was overwhelmingly the gainer’.14

Although it was not easy convincing the county education committee that the sculpture would be suitable, the commission was ultimately approved in 1949.13 The finished work was Moore’s first major bronze sculpture and his first large-scale sculpture to be editioned in multiple casts. According to Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud, ‘Henry’s fee had struck the education committee as excessive. So he reduced it to what he reckoned was cast price, about £750, covering casting, transport, materials, enlargement etc., on the understanding that he could make extra casts and dispose of them himself: a concession from which he was overwhelmingly the gainer’.14

From plaster to bronze

Henry Moore

Family Group 1945

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Family Group 1945

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

in the small version the split head of the man gives a vitality and interest necessary to the composition, particularly as all three heads have only slight indications of features. When it came to the life-size version, the figures each became obviously human, and related to each other and the split head of the man became impossible, for it was so unlike the woman and the child.16

Full-size plaster version of Family Group 1948–9

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Full-size plaster version of Family Group 1948–9

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph taken in 1949 of two full-size plaster versions of Family Group

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Photograph taken in 1949 of two full-size plaster versions of Family Group

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

While the first cast was still being made, Moore chose to have two other copies of the sculpture cast in bronze. Given the problems experienced by Fiorini, Moore decided to have these two examples made by the Rudier Foundry in Paris.21 This foundry had a distinguished reputation, and had cast many bronze sculptures by the French artist Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). At Rudier the two sculptures were cast using the sand casting technique in at least ten sections, which were then reassembled and secured with pins.22

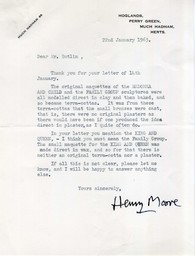

Tate and Family Group

Before they were even finished these two casts were quickly acquired by Moore’s New York dealer, Curt Valentin of the Buchholz Gallery. Valentin bought them for £2,000 each, and soon sold one to the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA) for £2,500. In a letter to Moore dated 17 February 1950, Valentin confirmed the MoMA sale and informed Moore that he was writing to Rudier to confirm that the sculpture would be ready for exhibition that autumn.23

It is probable that Moore discussed the possibility of Tate purchasing a cast of Family Group with the gallery’s director, John Rothenstein, in early 1950. In a letter to Rothenstein dated 4 April 1950, Moore wrote,

Here are the photographs of FAMILY GROUP. They are not as good photographs as I’d like them to be, because anyhow plaster is a material not easy to photograph ... I wrote to Curt Valentin + to Alfred Barr [director of MoMA], to know if they had any objections to my doing 4 casts instead of only 3 – I told them I wasn’t dying to make a fourth cast because each cast will have to have a month or more work on it by me after it’s delivered to me by the Bronze Foundry – though of course I would like a cast of it to be available for the Tate Gallery should the Tate Gallery like to consider it. I got the enclosed letter back from Curt Valentin – which looks to me that they all agree to a fourth cast if I press for it – but that Curt Valentin would like to sell his No 3 cast to the Tate (having sold No 2 cast to the Museum of Modern Art).24

Minutes from the meeting of Tate’s Board of Trustees dated 20 April 1950 record that the board provisionally agreed to purchase Family Group for £2000, pending a decision on how many examples would be cast.25 On 25 May Moore wrote to Rothenstein confirming that ‘I have decided to keep to my original intention of only having three casts’, and that he was travelling to Paris the following week to see how Rudier was progressing with the casting. Significantly, in this letter Moore also discussed the price of the sculpture set for Tate. Since Valentin had bought the sculpture for £2000, and Tate had agreed to pay £2000, Moore was aware that his dealer would not make any profit. To secure the sale, Moore wrote,

I have told him [Valentin] that his price to Tate can only be a very little more than £2000, and have suggested to him that it is £2,100. I am sure I can persuade him to be satisfied with half the commission he made on the Museum of Modern Art one, that is by me letting him have the second cast for £1,850 instead of £2,000. Although this means me losing a little, I am only too happy about it, to think that the Tate will be having this Group.26

On 1 June Rothenstein replied to Moore thanking him for arranging the price and sale of Family Group, stating that the trustees will ‘be very much gratified by the prospect of being able to purchase this work for Tate’.27 Just over two weeks later he confirmed that the trustees approved the purchase at their meeting on 15 June 1950. However, sometime between mid-June and early December Moore was approached by the American collector Nelson Rockefeller, who also wished to purchase an example of Family Group. Despite declaring earlier that he wanted to keep the edition to three, it seems that Moore was swayed by the prospect of selling a cast to this important collector, and he telephoned Rothenstein to discuss the matter. In a letter written on 4 December 1950 Rothenstein stated,

Immediately after speaking to you this morning, I rang up the Chairman and informed him of Nelson Rockefeller’s desire to have a fourth bronze of the “Family”, and of your own generous offer to arrange for a deduction of £500 from the price of our bronze, should the Board agree to the raising of the number from three to four. The Chairman willingly agrees and will report his action at the next Meeting.28

The second example of Family Group went on display at MoMA in February 1951, and by 23 February that year Tate’s example had been completed by Rudier, and was ready for shipping back to Moore’s studio.29 The sculpture was delivered to Moore in late March, and on 28 April 1951 Moore wrote to Rothenstein that ‘the cast is really excellent and I am very glad that we had it done in Paris’.30 However, Moore annotated the typed letter with a handwritten addendum, noting, ‘the patina is still being a problem, but I hope to have it more or less alright by this Monday – but if its not, it can still be changed’.31 Moore was working to a deadline as the sculpture was due to be included in his solo exhibition at Tate, which opened on 2 May 1951.32

Tate’s Family Group was included in the 1951 exhibition of Moore’s work, and has regularly been on display ever since. The sculpture was also exhibited in Moore’s major solo exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1978, organised to mark his eightieth birthday. The exhibition included all Moore’s sculptures held in the Tate collection, including the thirty-six sculptures presented as the Henry Moore Gift. For this occasion Family Group was exhibited in the Duveen Galleries on a plinth opposite Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387). Held between June and August, the exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.33

Reception and interpretation

Family Group 1948–9 installed at Barclay School, Stevenage

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Furze, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Family Group 1948–9 installed at Barclay School, Stevenage

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Furze, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In 1975 Moore responded to a letter from Evelyn S. Ringold, an American researcher investigating the representation of family life. In his letter Moore outlined the circumstances in which Family Group came to be made, and reflected that by the time the full-size bronze sculpture was cast, his daughter Mary,

was two years old and our family life was very happy indeed. Perhaps the family groups reflect this outlook. I don’t think I had any philosophy of English family life or American family life in mind, though, no doubt, my own childhood would have an influence. I was the seventh child of a family of eight, my childhood was very full and very happy.36

In 2006 the art historian Penelope Curtis suggested that the Family Group series – the drawings, maquettes and full-size bronzes – can be understood as ‘Moore’s own answer to the new ethos in British sculpture after the war, which returned to a much more recognisable human figure, and responded to the new opportunities for public sculpture arising out of state support for the arts within a culture of reconstruction’.37 Despite contemporary accusations that the figures resembled the skeletal survivors of Nazi concentration camps, Curtis asserted that ‘Moore was a generation older than the new wave of British sculptors ... whose style was angular and anxious, and it is likely that Moore’s comparative wholeness accorded better with people who wished to celebrate the arts of peace, rather than those of the cold war’.38

Family Group was initially cast in bronze in an edition of four. The first three casts remain in their original collections, at the Barclay School, Stevenage; Tate, London; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.39 The fourth bronze, formerly in the collection of Nelson Rockefeller, is now in the collection of the Hakone Open Air Museum in Japan.40 In addition to these four casts, Moore also cast an artist’s copy at the Rudier Foundry, which is now held in the Norton Simon Art Foundation in Pasadena.41 In 1995, in accordance with the artist’s wishes, the Henry Moore Foundation cast a second artist’s copy at the Morris Singer Foundry, Basingstoke, which remains in the Foundation’s collection.

Alice Correia

March 2014

Acknowledgements

This catalogue entry was compiled using research undertaken by Robert Sutton, Collaborative Doctoral Award student (University of York and Tate).

This catalogue entry was compiled using research undertaken by Robert Sutton, Collaborative Doctoral Award student (University of York and Tate).

Notes

See Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.83.

See Harry Rée, Educator Extraordinary: The Life and Achievement of Henry Morris, London 1973, pp.70–2.

Henry Moore cited in Farewell Night, Welcome Day, television programme, broadcast BBC, 4 January 1963, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.89.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816, p.13. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

See David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, 5th edn, London 1988, pp.14–15.

Henry Moore, letter to Martin Butlin, 22 January 1963, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23941.

Although this plaster working model has been dated to 1945, the revised shape of the father’s head – along with its fabrication in plaster, a material Moore had rarely used prior to the Barclay School commission – suggests that it was actually made in preparation for the full-size sculpture between 1947 and 1948.

In September 1994 Meadows recalled that in order to enlarge the plaster to scale he built a measuring frame over the version to be enlarged and another over the model. These frames both had rulers marking lengths in inches so that Meadows could read off a measurement from the smaller ruler and apply it directly to the enlargement. Each measurement referred to a specific point on the surface of the model, which could then be recreated to the correct scale. Using frames and rulers avoided having to make complicated calculations, and ‘was really a very direct thing and could be done in a matter of seconds’. See ‘Interviews with Bernard Meadows’, 22 September 1994, p.24, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

‘Interviews with Bernard Meadows’, p.45. Numerous photographs at the Henry Moore Foundation show a plaster of Family Group in various stages of development in Moore’s studio, but it is unclear whether these photographs show the original or second plaster.

Sand casting is a technique whereby a model is buried in sand to create a mould from which the bronze can be cast. Sand casting is quicker and less labour-intensive than the lost wax method but is also generally less suitable for reproducing very intricate shapes or surface details.

See http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/sculpture-and-drawings-henry-moore , accessed 14 March 2014.

These figures are based on those listed in a memo in the exhibition’s records. See Tate Public Records TG 92/344/2.

Anon., ‘“Belsen” Statue Came in the Night’, Daily Dispatch, 3 November 1950, cited in Berthoud 2003, p.261.

See http://www.nortonsimon.org/collections/browse_artist.php?name=Moore%2C+Henry&resultnum=4 , accessed 17 March 2014.

Related essays

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www