Walter Richard Sickert Baccarat - the Fur Cape 1920

Walter Richard Sickert,

Baccarat - the Fur Cape

1920

This painting depicts fashionable British tourists of the leisured classes playing baccarat in the private rooms of Dieppe’s Casino Mauresque. Ferry services across the Channel were reinstated shortly after the First World War, when the French seaside resort saw a resurgence in holidaymakers. Baccarat was illegal in England at the time, and Sickert’s bluntly obscured view of the gambling table and enraptured players under green lampshades expresses a quality of illicit excitement. The female figure in the foreground, with her back to the viewer, has no identifiable features apart from her flashy accoutrements – a broad-brimmed orange hat and fur cape.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Baccarat – The Fur Cape

1920

Oil paint on canvas

591 x 419 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom right

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05089

1920

Oil paint on canvas

591 x 419 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Sickert’ in black paint bottom right

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05089

Ownership history

Purchased by Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, London, from the Goupil Gallery, London, 1921 (77); by descent to his wife, Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, on his death 6 October 1931, by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1940.

Exhibition history

1921

Goupil Gallery Salon, Goupil Gallery, London, November–December 1921 (77, as ‘Baccarat No.1’).

1928

An Exhibition of Modern Art, The French Gallery, London, Autumn 1928 (19, as ‘The Fur Cloak’).

1930

Contemporary British Painting, Knoedler’s Galleries, London, March 1930 (25).

1933

Retrospective Exhibition of Pictures by Sickert, Agnew’s, London, November–December 1933 (6, as ‘Baccarat’).

1936

A Loan Exhibition of Paintings & Drawings, St John Ambulance Hall, Kendal, April–May 1936 (15, as ‘Baccarat’).

1942

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, National Gallery, London, April–May 1942 (116, as ‘Baccarat’).

1942–3

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Royal Exchange, London, July–August 1942, Cheltenham Art Gallery, September 1942, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October 1942, Galleries of Birmingham Society of Arts, November–December 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, January–February 1943, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February–March 1943, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, March–April 1943, Manchester City Art Gallery, April–May 1943, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, May–June 1943, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, June 1943, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvingrove, July 1943, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, August 1943 (78, as ‘Baccarat’).

1966

Looking at Pictures, Central Library, Luton, March 1966 (no catalogue found).

1968

Fifth Adelaide Festival of Arts: Walter Sickert, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 1968 (51).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (22, reproduced).

2010

The Art of Walter Sickert, The Lightbox, Woking, May–July 2010 (no catalogue).

References

1941

‘The Tate Gallery: Wartime Acquisitions’, Burlington Magazine, vol.78, February 1941, p.57.

1943

Lillian Browse and R.H. Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, p.59, reproduced pl.54.

1949

Notes and Sketches by Sickert from the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1949, pp.18, 20.

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York 1955, reproduced pl.39.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.61, 102.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.629–30.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, p.161–2, 379.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, pp.111, 473–4, no.545.

Technique and condition

Sickert painted on a pre-primed canvas bought from Paul Foinet Fils, who also supplied him with the canvas for Roquefort (Tate N03847). The fine linen canvas is attached to a five-membered stretcher with steel tacks, which have rusted. There is no visible evidence of a discrete sizing layer and the priming is very lean and water soluble. It is composed of a single layer of gypsum probably in a tempera medium, providing an ‘absorbent ground’ on which to paint in oils (see Tate N05092).1 It is perhaps one of Foinet Fils’ ‘toile, Venetienne, demi-absorbente’, a semi-absorbent Venetian canvas, so called because absorbent grounds were once thought to be the secret of the brilliant colour of paintings of the Venetian School.2

The artist’s initial design is not visible but bright areas of pink and light ochre can be seen through gaps in the paint suggesting a camaieu application to lay out the main areas of light and shade (see Tate N04364). The painting is more impressionist in style and application and the figures in the background have a photographic feel. Lean paint applied on top of the lean primer and camaieu has been absorbed into the prepared canvas to leave a very dry surface. Its application must have been very stiff and viscous and there is little working and sweetening (see Tate N03847) of the paint and no fluidity in the application of any lines. Some sharp impasto has been produced in areas of thicker paint, principally applied in the later stages. In contrast, the evidence of canvas texture remains in many of the least worked parts of the composition, although nearly all of the white ground has been covered, at least by the camaieu and often by further paint. Where white was needed in the final image it has been applied as opaque white paint, for example in the overhead lights over the card tables. The abstract shape of the chair, the texture of the coat and the sitter’s hat dominate the composition leaving only a small area for the figures in the background, which define the subject of the painting. There is no major alteration or reworking, although the depiction of the fur of the coat is rather scrubbed in appearance. It may be that the thin layer of varnish, which has soaked unevenly into the paint film reducing its lean surface, has had a detrimental effect on the appearance of the fur coat, or that Sickert was simply more concerned with the process of seeing the entire scene, perhaps drawing the eye away from the seated figure, which blocks our view.

Stephen Hackney

November 2005

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', November 2005, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Baccarat – The Fur Cape 1920 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Baccarat – The Fur Cape shows the eponymous game of cards under way in the casino at Dieppe in 1920. Eight players (or perhaps more), both men and women, are visible around the green baize table, which is numbered ‘100’ and lit from above by green fringed lampshades. Sickert’s interest is not engaged by the progress of the game but rather by the appearance of the wealthy and fashionable players. The table is completely obscured by the central figure, a woman in an orange fur cape and a bright orange, broad-brimmed hat trimmed with a red feather. She sits in a chair with a curved frame, her back to the viewer so that nothing is visible of her except her clothes. The appearance of the other gamblers at the table is also obscured. Sickert has reduced the figures to broken patches of acidic colour reflecting the harsh, transforming glare of the electric light. Particularly strange is the trio of figures in the background partially hidden by the orange hat. The two standing figures with blank white faces are recognisable as women only by their green hats, while the man seated at the table in front of them has a green and pink face which gives him a bizarre mask-like appearance.

Sickert produced a large number of casino paintings and drawings during this period, most of which focus on the activity in the baccarat room. The art historian Wendy Baron has identified a related oil painting to Tate’s version in Phoenix Art Museum.1 Other known finished works are:

Baccarat 1920 (private collection, formerly ?Lord and Lady Cottesloe)2

Baccarat 1920 (whereabouts unknown, inscribed ‘à Mademoiselle Levache | Souvenir de Walter et Christine Sickert – Envermeu 1920’)3

Baccarat, Dieppe 1920 (City Art Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand)4

Baccarat 1920 (private collection, formerly Walter Howarth)5

Baccarat 1920 (whereabouts unknown, inscribed ‘à Mademoiselle Levache | Souvenir de Walter et Christine Sickert – Envermeu 1920’)3

Baccarat, Dieppe 1920 (City Art Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand)4

Baccarat 1920 (private collection, formerly Walter Howarth)5

The composition of the latter two works is close in appearance to Tate’s painting. Baccarat, Dieppe shows the back of the lady seated at the table, flanked by two male players. Like the woman in Tate’s version, the position at which she sits makes it impossible to see her face, or any identifying features other than her clothes. Sickert also completed an etching and drypoint based upon the Cottesloe picture,6 while another casino subject is Banco! (whereabouts unknown).7

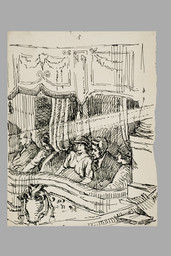

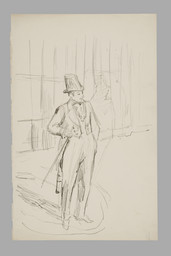

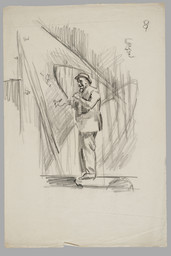

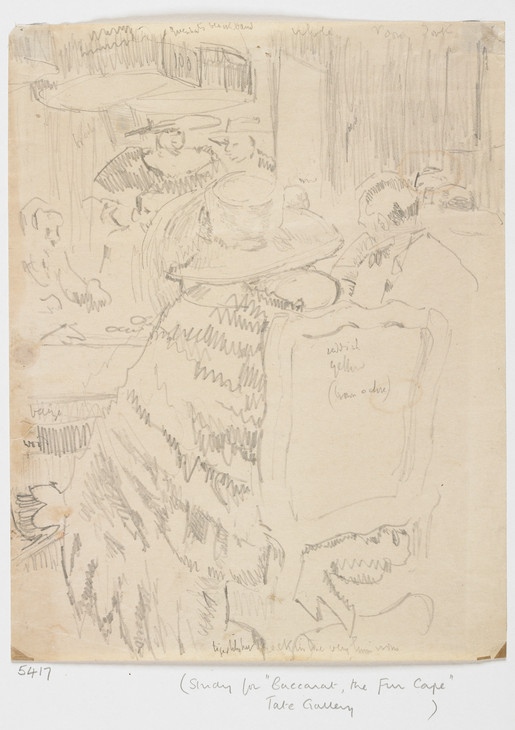

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Study for 'Baccarat – The Fur Cape' 1920

Pencil on paper

272 x 210 mm

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Study for 'Baccarat – The Fur Cape' 1920

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

Casino Mauresque

A casino had existed in Dieppe, on the seafront at one end of the Rue Aguado, since 1822, but the building which Sickert depicted was the third on that site, known as ‘Le casino mauresque’ (The Moorish Casino). Built in 1886 as part of a larger municipal scheme to improve the leisure services in the town, the ‘Casino Mauresque’ took its name from the moorish style of its architecture.13 Designed by Isidore Bloch, the façade was decorated with horizontal stripes of red and buff coloured bricks, topped by domes of green copper, and the entrance was dominated by two towers surmounted by ornamental minarets.14 The painter Jacques-Emile Blanche described the effect as ‘ridiculous but amusing’. It was a well-known landmark and an important venue for the Dieppe ‘season’ comprising a large complex of facilities which included a café-restaurant, hot baths, extensive lawns and flower gardens, a terrace overlooking the beach, bathing huts and a vast hall for concerts, plays and dances.15 In 1904, Sickert had painted The Casino. Boulevard de Verdun,16 which recorded the view across the seafront looking towards the distinctive outline of the casino’s towers in the distance. The building survived until 1926, by which time the once popular style of the fin-de-siècle appeared outdated and the casino was redeveloped in a modern art deco style.

The true purpose of the casino, of course, was to encourage tourists, particularly the large contingent of British visitors, to part with their money in the gaming rooms. Arthur Symons (1865–1945), the poet and critic and friend of Sickert’s, described the atmosphere in his travel guide, Cities and Sea-Coasts and Islands, published in 1918:

The Casino has many charms. You can dance there, listen to music, walk or sit on the terrace in the sun, write your letters in the reading-room on the very pictorial paper which is so carefully doled out to you; but it is for none of these things that the Casino exists, it is in none of these things that there lies the unique fascination of the Casino. The Casino, properly speaking, is only a gorgeous stable for the little horses [Petits chevaux – a type of game]. All the rooms in the Casino open into the room of the green tables; all the alleys of the gardens lead there. In the intervals of the concert, if you wish to stroll for a few minutes on the terrace, you have to pass through the room; you see the avid circle about the tables, hear the swish of the horses, the monotonous ‘Faites vos jeux, Messieurs ... Les jeux sont faits ... Rien ne va plus’, and then, after the expectant pause, the number: ‘L’as numéro un.’ And in time, however strong, or however idle, or however indifferent you are, you will be drawn into that fascinated circle, you will be seized by the irresistible impulse, you will begin to play.17

In the main hall patrons of the casino could play Petits chevaux and boule, a type of roulette (see Tate N04738). However, payment of a subscription fee of ten francs would also permit admission to the Baccarat Club where the serious gambling went on.18 Played with multiple decks of cards, the object of Baccarat is to bet on a hand of two or three cards with a value as close to nine as possible. Cards are dealt to one of the players and the banker from the ‘shoe’, and bets are placed by all seated at the table on which hand will be closest to nine. The name derives from the Italian word ‘Baccara’ meaning zero, a title which refers to the fact that picture cards and tens count as zero. Also sometimes known in France as ‘chemin de fer’ (literally ‘railway’), the game was traditionally the preserve of the richer, leisured classes and was played in a specially designated area of the casino, away from the more common pastimes such as roulette or boule. A dress code was in place and the crowd seen playing in the Baccarat Rooms was noticeably smarter and more fashionable than people elsewhere in the casino.

Dieppe

Dieppe had been a favourite subject with Sickert since the 1880s, yet despite his familiarity with the town he tended to view it with a tourist’s eyes, and had previously restricted himself to painting townscapes with recognisable landmarks such as the statue of Duquesne and the church, St Jacques (see Tate N05096 and N05094). He had not usually painted Dieppe interiors despite completing so many in London, Venice and Paris. It was also unusual for him to depict fashionable society since he usually preferred the seedier world of the working classes. In the summer of 1920, however, he turned his attention for the first time away from Dieppe’s streets and vistas, and became interested in the depiction of the town as a resort. The fashionable ‘season’ lasted from June to October, during which time Dieppe was full of British holidaymakers. Sickert painted some of the diversions on offer such as the circus and the nightlife at Vernet’s, a café chantant on the Quai Henri IV,19 as well as turning his attention to the casino.

He may have been encouraged to consider these new subjects by a shared sense of the renaissance of Dieppe in the years following the First World War. Between 1914 and 1918 the Dieppe season was utterly closed down. The ferry service between England and France was suspended, making it impossible for British tourists to cross the Channel. The casino itself was closed for the duration and used as a hospital. After the war the town struggled to recover from its long, enforced state of inactivity, and it was not until 1920 that the British tourists began to return in force and the delights of the season were fully resumed.20 Sickert’s paintings from this period may capture some of the prevalent excitement, relief and delight that Dieppe was once again a place for leisure and enjoyment. In 1920 he was living at nearby Envermeu and would catch the train into Dieppe for the evening.21 Play commenced at the casino at midnight and went on until the early hours of the morning.22 The art dealer Oliver Brown recalled encountering Sickert at the casino one night making impromptu sketches:

My wife and I were holiday-making in Dieppe about 1920, and in the baccarat of the Casino which we visited we noticed a figure in evening-dress, with an opera cloak, seated in a corner drawing on small scraps of paper. It was Sickert himself. We went over to talk to him. He gaily remarked: ‘I am the only one who will make any money in this room.’23

Gambling

Despite the elaborate surroundings and fashionable crowd the pleasures of the casino nevertheless revolved around gambling and were therefore considered by many to be a vice, rather than a harmless recreational pastime. One guide to the game, written by Professor Louis Hoffman and published in 1891, ends with the following dire warning:

Happily, Baccarat is in England an unlawful game, and long may it continue so. Apart from its sordid interest as a possible means of acquiring money without working for it, it is beneath contempt – many games of the schoolroom taking far higher rank as intellectual recreations. Its only attraction, as we have said, is the prospect of gain, and after the exposures made here it must be sufficiently obvious that such a prospect is, for the honest player, a very shadowy one. Instead of playing on an equal footing, he simply stands to lose. If, knowing this, any honest reader of these pages still plays Baccarat, he will well deserve the fate which will sooner or later befall him.24

The sort of fate that might befall the unscrupulous Baccarat player was evidenced in 1890 by the affair, which became known as the Royal Baccarat Scandal, or the Tranby Croft Scandal. Although illegal, the game was a favourite of the future King Edward VII who frequently played it in private with his friends. On one such occasion, one of the party, Sir William Gordon Cumming, was accused of cheating and was subsequently ostracised in society. To defend his honour he sued in a civil court and the Prince of Wales was forced to testify in public as a witness where his own participation was revealed.25

The whiff of scandal historically associated with the game would have appealed to Sickert’s appetite for controversial subject matter, but the stigma of being a player evidently troubled even a liberated postwar clientele. One of Sickert’s acquaintances who frequented the casino at Dieppe was Lady Blanche Hozier, whose daughter Clementine had married Winston Churchill in 1908. Described by Jacques-Émile Blanche as an ‘impenitent gambler’,26 she objected to Sickert recording the proceedings in the Baccarat Club, concerned that his drawings might lead to some of the players being publicly recognised.27 Henceforth, Sickert was obliged to make his sketches surreptitiously on small cards held underneath the table (some of which are now in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford).

In Baccarat – The Fur Cape, Sickert has minimised the visual effect of the elaborate surroundings of the casino and the fashionable attire of the players. This is clearly a deliberate strategy comparable to some of his paintings of London music halls where he contrasts the gaudy, extravagant décor of the interior with the working-class audience seated in the gods, for example in Gallery of the Old Bedford c.1895 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool).28 Rather than glamorising Dieppe’s high society, however, Sickert introduces an element of caricature, making his characters appear somewhat seedy and ridiculous. The player in Baccarat is totally enveloped in her hat and fur cloak, almost like an excessive disguise designed to preserve the anonymity of the sitter, and yet simultaneously accentuating her presence. The lack of openness about the identity of the players, and the feeling of exclusion from the game experienced by the viewer, imbues the scene with a sense of illicit pleasures enjoyed furtively at night. Their total absorption in the game and minimal interaction with one another betrays the fact that the casino is more than simply a fashionable place at which to be seen. Symons commented on the attraction of gambling, which was as addictive to women as to men:

The fascination of gambling, to the real amateur of the thing, is stronger than any other passion. Men forget that a beautiful woman is sitting opposite to them; women do not so much as notice that a more beautiful toilette than their own has just come into the room. I have seen the most famous professional beauties of Paris sit at those green tables, and not a soul has looked at them except the croupiers and myself.29

It was not Sickert’s habit to take a moral stance within his works but his own attitude to gambling can perhaps be gauged from two later paintings, almost identical in appearance, The Old Fool 1924 (Sir John and Lady Elliott),30 and The System 1924–8 (Bevan Collection).31 Like Baccarat – The Fur Cape, the paintings focus on a single figure, but in this case the gambler is an old man who sits at the table with his head in his hands in despair, having presumably lost his money during a game of boule.

Nicola Moorby

May 2005

Notes

Reproduced ibid., no.543 and in 20th Century British and Irish Art, Christie’s, London, 19 November 2004 (lot 88).

Baron 2006, no.543.1; reproduced in Paintings by Richard Sickert A.R.A., exhibition catalogue, Beaux Arts Gallery, London 1933 (27).

Ibid., no.546; reproduced in Sickert 1860–1942, exhibition catalogue, Roland, Browse and Delbanco, London 1960 (7).

Reproduced in Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000, no.193.

Sickert: Retrospective Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1929 (75, reproduced in between pp.8–9).

Exhibited in Sickert and Blanche, Parkin Gallery, London 1982 (18); reproduced in Tate Catalogue file.

Anaïs Kot, ‘Une ville, cinq casinos’, Les Dossiers de quiquengrogne, July 2000, http://www.dieppe.fr/system/wysiwyg_files/datas/227/original/quiquengrogne43.pdf?1255445485 , accessed May 2005.

Simona Pakenham, Sixty Miles from England: The English at Dieppe 1814–1914, London, Melbourne and Toronto 1967, p.136.

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973, fig.107; see also The Road to the Casino, Dieppe 1907, oil on board, reproduced in Modern British Art, Sotheby’s, London, 2 June 2004 (lot 21).

George Day, Seaford, Newhaven and Lewes with a Chapter upon Dieppe: A Handbook for Visitors and Residents, London 1912, p.84.

Vernet’s, Dieppe 1920, private collection, reproduced in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1992 (96).

Professor Louis Hoffman, Baccarat: Fair and Foul; Being an Explanation of the Game, and a Warning Against its Dangers, London 1891, pp.118–19.

Related biographies

Related archive items

-

Walter Richard SickertDrawing

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Baccarat – The Fur Cape 1920 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www