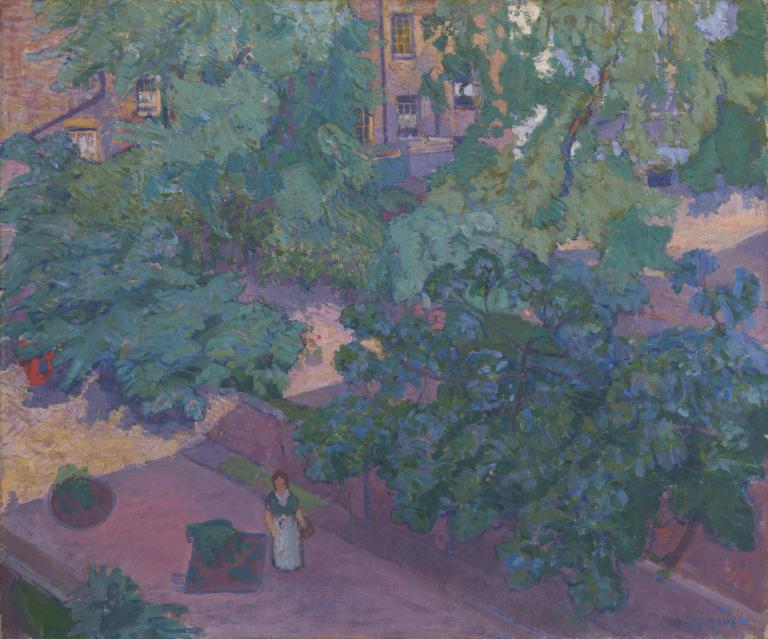

Spencer Gore The Fig Tree c.1912

Spencer Gore,

The Fig Tree

c.1912

Gore often painted the view looking out of the windows of his lodgings, including several different compositions of this fig tree in various seasons of the year. The painting is dominated by the diagonal shadow cast from the building onto the garden, which meets the garden walls running across the picture at opposing angles. The figure in the foreground might be Gore’s wife, Mollie.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Fig Tree

c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 760 mm

Inscribed studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom right

Bequeathed by J.W. Freshfield 1955

T00028

c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 760 mm

Inscribed studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom right

Bequeathed by J.W. Freshfield 1955

T00028

Ownership history

Mrs Mary Johanna Gore, the artist’s widow; bought at Redfern Gallery, London, 1939 for £150 by J.W. Freshfield, by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1955.

Exhibition history

1913

Paintings by Spencer F. Gore and Harold Gilman, Carfax Gallery, London, January 1913 (46, 30 guineas).

1913

Forty-Ninth Exhibition of Modern Pictures, New English Art Club, Royal Society of British Artists Galleries, London, Summer 1913 (151).

1913–14

English Post Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, December 1913–January 1914 (50).

1939

The Camden Town Group, Redfern Gallery, London, March–April 1939 (16).

1939

Loan to the Tate Gallery by J.W. Freshfield, April 1939.

1940

British Painting since Whistler, National Gallery, London, March–August 1940 (144).

1944–5

Camden Town Group, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Wakefield Museum and Art Gallery, July 1944, Jordans School, Chalfont St Giles, August 1944, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, August–September 1944, Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead, September–October 1944, Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport, October–November 1944, Reading Museum and Art Gallery, December 1944, Hanley Public Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke on Trent, January–February 1945 (29).

1968

Secretary of State for Education and Science, Department of the Environment, Marsham Street, London 1968, (long loan).

2004–5

Art of the Garden: The Garden in British Art, 1800 to the Present Day, Tate Britain, London, June–August 2004, Ulster Museum, Belfast, October 2004–February 2005, Manchester Art Gallery, March–May 2005 (10, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (26, reproduced).

References

1960

Mervyn Levy, Drawing and Painting for Young People, London 1960, reproduced opposite p.113.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.249.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.48, 374.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, pp.55, 182.

Technique and condition

The Fig Tree is painted in artists’ oil paint on primed stretched canvas. The cloth appears to be linen and has a close plain weave. It is attached to a four-member stretcher with tacks that remain in their original position. The canvas is probably sized and has white priming that appears quite lean. It is evenly applied and retains the relatively smooth texture of the canvas; most of Gore’s other works in the Tate collection are on coarse-weave canvas.

No squaring-up or preliminary drawing is visible but the preparatory surface is covered by a substantial paint film. Drawing in the paint occurs at all levels to define the forms that may have got lost in the flurry of brushstrokes. The paint appears to be oil colour applied in several layers forming a generally lean and brittle film. The leanness of the paint layer may be due to the superimposition of several layers thinned with dilutent without the addition of medium, combined with an absorbent ground (see also Tate N04675). An accumulation of vigorous short brushstrokes has left a ragged and spiky texture that covers most of the surface. The lower applications were sufficiently dry when over-painted to retain their form. Occasionally, the white priming is visible where thinner broken strokes of paint that have not been over-painted leave it exposed.

The composition is dominated by the strong diagonal shadow cast from the building from which the scene is viewed. The apple and blue greens of the writhing foliage of the fig and other trees are contrasted with the warm oranges of the houses and walled gardens in sunlight and darker violets and mauves of the shadows. Colour rather than extreme tonal contrasts are accentuated to convey the sense of light, as with the rapid stitched accents of pink laid onto the sunlit greens and few restrained accents of bright red. The vigorous organic growth of the trees towards light is contrasted to the geometric forms of the walls, windows, drain pipes and shadows of the rows of houses that confine the trees and block out the light. The painting is unvarnished.

Roy Perry

April 2004

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', April 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘The Fig Tree c.1912 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for a Mural Decoration for 'The Cave of the Golden Calf' 1912

Oil paint and graphite on paper mounted on card

support: 305 x 605 mm

Tate T00446

Purchased 1961

Fig.1

Spencer Gore

Study for a Mural Decoration for 'The Cave of the Golden Calf' 1912

Tate T00446

Other paintings of the Gores’ garden include Down the Garden, 2 Houghton Place 1912 (private collection)3 and Spring in North London 1912 (private collection).4 In The Fig Tree, as with his other paintings of trees and foliage, Gore concentrated on the textures, patterns and colours. The impressionist technique of applying short dabs of colour has been replaced here with a broader painting style, but one which follows the impressionist belief in coloured shadows. As with many other works, Gore here constructs a composition that relies on the tension of diagonal lines, the garden walls running across the picture, one of them cutting off the bottom corner, but unified by the spreading forms of the vegetation. Gore paid particular attention to the harmony of all his pictures’ colour schemes. He wrote to his pupil, John Doman Turner, explaining:

All colour is relative and influenced by its surroundings. If you have a red house in a green field against a blue sky, in whatever scale you paint them a tint or the fullest colour you can get, each has some effect on the other. The removal of one would create a new relation between the other two. It may be very subtle or very marked, as in a sunset sky and green fields: if you blot out the sky the colour of the grass is entirely different, and the best thing to trust to for these relations is your eye. The only positive colour would be one of the principal colours of the spectrum isolated, a pure colour, and you might say a colour in a painting was too positive when it approached too near a pure colour for its place in the picture. But a picture might be entirely painted in pure colours.5

Gore’s advice to Doman Turner, to trust his eye for colour harmony rather than to theory, shows a practical and flexible attitude to painting. In another letter to his pupil, Gore wrote dismissively of neo-impressionism:

Neo-Impressionist was the name given to the people who tried to reduce the system of divided colour to a science. Every colour divided up into its purest forms put on in dots of equal size. The two chief exponents were Signac and Seurat, Seurat died Signac is still alive, Lucien Pissarro learnt to paint in this manner. It was not a great success because it made a painting very mechanical and took a long time to do. Oil paint also is not light but mud. Think for yourself.6

Gore first exhibited The Fig Tree at the exhibition he and Harold Gilman held at the Carfax Gallery in January 1913. The asking price was 30 guineas, one of the most expensive of his pictures in the show; The Beanfield (Tate T01859), for instance, was only priced 12 guineas because of its smaller size. The pictures that had higher prices in the exhibition were all either garden or music-hall scenes. Gore held business-like views about the relative value of his pictures. In 1909 he had written to Doman Turner:

The price of any painting would depend on the demand there was for it. An artist might be able to sell one kind of painting easily and another scarcely anybody would look at. The price of one would go up and the other down, or perhaps he would not try and sell it at all. If I priced one at £10.10 and another at £12.12 it would only be because one would be the sort of thing people were more likely to buy and not because I thought it a better painting. People don’t buy things because they are good paintings, but because there is something pretty or attractive about them, or because it is what they are accustomed to expect from the painter. Very many portraits of men by Gainsborough are far better than the women, but one goes for hundreds and the other for thousands. The price is the last thing to judge by.7

This might suggest, therefore, that the more numerous subjects of gardens, parks and music halls that Gore made were partly painted because there was a stronger market for them, a consideration in his choice of subject matter from which it was impossible to escape.

Gilman painted a view from Gore’s window of the tree on other side of the garden in The Tree, from 2 Houghton Place 1912 (private collection).8

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Related biographies

Related essays

- The Camden Town Group and Early Twentieth-Century Ruralism Ysanne Holt

- The Camden Town Group: Then and Now Ysanne Holt

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘The Fig Tree c.1912 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www