Painters of Modern Life: The Camden Town Group

Robert Upstone

Modern but not modernist in style, Camden Town painting was at its height in the years following the death of Queen Victoria and before the dramatic changes in British society and culture that occurred during and after the First World War. In this essay, first published in the Tate Britain catalogue Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group (2008), Robert Upstone examines the artistic and historical context of the Camden Town Group.

Founded in 1911, the Camden Group had only a brief life, but heralded a new spirit in British painting. Marking a particular moment in art’s move towards the modern, it was soon overtaken by the abstraction of Wyndham Lewis and vorticism, and the authentic modernism of David Bomberg, Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and others. There were just three Camden Town exhibitions, all held at the basement space of the Carfax Gallery in Bury Street, St James’s, in June and December 1911 and December 1912. Each of the sixteen painter members was permitted to show four works, which were hung together. With their pulsating colour harmonies and urban subject matter, the Group were consciously identified as modern but they occupied a comfortable – and perhaps quintessentially British – middle ground between tradition and the truly avant-garde. At the time of the Group’s founding, British art was fairly isolated from the radical developments of cubist abstraction that had taken place in Paris. Little advanced continental art was visible in London until the explosive impact of Roger Fry’s exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists in 1910–11. But the Camden Town Group’s choice of everyday subjects from London life, their bold, anti-naturalistic colouring and – in the case of some members – an interest in progressively simplifying forms, presented a type of painting that however briefly was new and different in the London of 1911. By breaking the rules of Edwardian propriety and selecting subjects from working-class life or the city itself, they retain a sympathetic position, capturing an experience of London that still has resonance.

What then are the unifying factors that distinguish Camden Town painting? If anything it is a shared interest in common urban subjects, the streets and people of London, everyday scenes, sometimes mundane, sometimes extraordinary. They depict chars and coster girls; nudes in shabby north London bedrooms, the dust caught in shafts of sunlight; suburban street scenes; the cab trade; the popular entertainment of the music hall, and the audience in the cheap seats and gallery who came to see it; a working men’s eating house; a notorious murder; the lassitude of isolated figures in an Edwardian park. There is also a distinctive Camden Town style. These subjects are all painted in dry, thick, crusty paint, applied in broken touches, either in brilliant, vibrating colour combinations of mauves, pinks and greens, as is the case with Spencer Gore, Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman and Robert Bevan, or in the darker, richer, Old-Master tones favoured by Walter Sickert. As a phenomenon Camden Town painting predates the formation of the Group itself: it goes back to 1906 when Sickert was painting La Hollandaise (fig.1) in a grimy bedroom, and to Gore’s emulation of him in 1907, and it continues beyond the period of its cohesive group identity through the years of the First World War, when Gilman painted his iconic studies of his landlady Mrs Mounter in his rooms in Maple Street off Tottenham Court Road (fig.2). But in its collective egalitarian belief in the pathos of ordinary city life, its ancestry lay with Sickert’s paintings of the music hall in the 1880s and 1890s, and his declaration, in the preface to the only exhibition of the ‘London Impressionists’ in December 1889, of his strong belief that the mission of the Impressionist artist was to study and reproduce the beauty of nature in all forms, and that in his view Impressionism:

does not admit the narrow interpretation of the word ‘Nature’ which would stop short outside the four-mile radius. It is, on the contrary, strong in the belief that for those who live in the most wonderful and complex city in the world, the most fruitful course of study lies in a persistent effort to render the magic and the poetry which they daily see around them.1

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

La Hollandaise c.1906

Oil paint on canvas

support: 511 x 406 mm; frame: 722 x 630 x 104 mm

Tate T03548

Purchased 1983

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

La Hollandaise c.1906

Tate T03548

© Tate

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 406 mm; frame: 808 x 605 x 93 mm

Tate N05317

Purchased 1942

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Tate N05317

Nor was this itself a particularly new idea. Going back as far as 1863, in his essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, Baudelaire had called for contemporary existence to form the subject of a vibrant new art that suited the modernity of the times, and in particular the new metropolitan experience. And as early as 1848, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had declared their own aim to be painters of modern life subjects. But what was different for the Camden Town Group was the position that London now occupied in the shared consciousness of the British public, and they were not alone in responding to it. The experience of the city, glimpses into ordinary peoples’ lives and the proximity of different classes featured as the background for a new breed of naturalist literature,2 written by among others Arnold Bennett, H.G. Wells, Joseph Conrad and Somerset Maugham, the last of whom purchased one of Gore’s Mornington Crescent paintings at the Group’s first show.3 E.M. Forster’s stories frequently revolve around the disjunction between people with different principles or backgrounds. In Howards End (1910) London is the environment in which intellectual, upper middle and working class characters collide, with tragic consequences; Forster’s entreaty is ‘only connect’. The growth and dominance of the city was a leitmotif for Edwardian Britain. By 1910 only about a fifth of the population lived in the countryside.4 In London, motor cars and buses became a normal sight and by 1910 horse cabs in the metropolis were outnumbered by motors.5 Traffic jams and crowded pavements, a modern Underground system, electric lighting, telephones, film shows, aeroplanes at Hendon – all these things gave a distinctly modern flavour to the experience of London, albeit one that mixed glimpses of grandeur and technological advancement with grime, the decaying city of the past and dysfunctional social relations. This very distinct urban flavour lent a particular character to the subject matter of the Camden Town Group.

This was also a time of some economic and social instability, and one that seems therefore to have nurtured new cultural developments. The gap between Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 is an awkward period to define, but it is one that sits as part of much longer narratives of economic progress and decline, of cultural change and fissure. While the period is generally described as Edwardian, Edward VII died in 1910. In our occasionally simplified mental impressions it rests isolated, a hiatus between the stereotyped strict repression of Victorian society and the unfettered horror of the Great War. It is perhaps a world we think we know best through Merchant Ivory film adaptations of Forster’s novels. We have resting in our minds images propagated by such films of stability, of endless golden summers, of tea on middle class lawns and sumptuous fashions, of a calm, upright, well-ordered society, immortalised in paint by John Singer Sargent, William Orpen and John Lavery. Yet this was the era in which the word ‘crisis’ was first coined. It was a period that began with the bitter conflict of one war, against the Boer settlers of South Africa, and ended with the greater international calamity of another’s outbreak. In between, British society was often anything but calm.

By 1913 British industrial production was the highest it had ever been, but Britain had lost its position of economic global dominance. In 1860 it had produced a greater proportion by an enormous degree of the world’s coal, pig iron, steel and cotton. But by 1911–13 Britain had been overtaken in all four of these areas by the United States, by a similarly large margin. In steel production alone, the United States generated four times more than Britain. And following America, Germany was mostly in second place for world heavy industrial production, except in cotton, due to British imperial possessions.6 British agriculture was in a similarly vulnerable position. Cheap American grain imports constantly drove down prices and already narrow profit margins, and lowered the value of land and the income of those who owned it. Similar negative effects were created by imports of cheap tinned and preserved foods from the Empire. In manufacturing, Britain had surrendered its position as the workshop of the world. It had been overtaken, again by America, and much of British investment was not at home but abroad. Britain was becoming ‘a parasitic rather than a competitive economy, living off the remains of world monopoly, the underdeveloped world, her past accumulations of wealth and the advance of her rivals.’7 The British economy shrank from industrial competition, and instead focussed on the magnificent profits that were possible from being the hub of international finance and trade with its rivals.

Wages stagnated, and prices went up somewhat. Life expectancy was higher than it had ever been, due to improving social conditions, and nutritional and medical advances. Infant mortality figures declined while the population as a whole soared. The 1906 general election brought a certain polarisation of social expectation; it was a landslide win for the Liberals, but Labour won its first sizeable portion of seats. Liberal social reform policies were set against worsening relations with the House of Lords, and the blocking of legislation. Amid rising prices, Labour relation troubles flared, and strikes became a source of concern to cadres of the right who wanted a return to deference and stability. Votes for women became an increasingly bitter struggle. Founded in 1903, the Women’s Social and Political Union led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst marshalled half a million at a rally in Hyde Park in 1908. Growing progressively militant, the movement followed a strategy of direct action – a bomb was planted in Westminster Abbey and there was a letter bomb campaign; country houses of government figures were burnt, including that of David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer; churches and railway carriages were torched, phone lines cut, government office windows broken, and members refused to pay their taxes. Those sent to prison went on hunger strike and were force fed; Emily Davison threw herself under the King’s horse at Ascot in 1913 and was killed; and in March 1914 Mary Richardson slashed Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus with a meat cleaver in the National Gallery.

Amid the domestic discord of strikes, suffragetism and renewed calls for an independent Ireland, a wave of nationalistic fervour swept Britain, a reaction to rising tensions in Anglo-German relations. Britain was angered by German support of the Boers during the South African War (1899–1902) and by Kaiser Wilhelm’s pursuit of colonies in Africa and elsewhere to rival the British Empire. For some decades in the nineteenth century Britain was the principal European manufacturer of consumer goods, but by the beginning of the new century Germany had become a significant rival. The Kaiser’s decision to double the size of the German navy led to a naval arms race with Britain, whose position of maritime supremacy was threatened for the first time since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Britain’s answer was to develop the Dreadnought battleship, the largest and most heavily armed warship the world had ever known, the first of which appeared in 1906. Such craft were viewed as the principal deterrent to imminent German invasion, fear of which was rife. It formed the subject of best-selling novels such as The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by Erskine Childers, and The Invasion of England (1905) by William le Queux, which was as popular in Germany as Britain and had different endings in each country. Anxieties reached frenzied levels in 1909, when rumours, newspaper stories and Parliamentary questions together whipped up worries about invasion and espionage. Spurious sightings of zeppelins were reported, and on 12 May 1909 the MP for Grimsby, Sir George Doughty, claimed that two ships full of German soldiers had sailed unchallenged in and out of the River Humber.8 In the Commons on 19 May 1909 the MP for Frome asked the Secretary for War, who dismissed it as nonsense, if he could confirm the rumour that 66,000 German soldiers were resident in southern England awaiting orders, and that a cache of rifles was hidden for them in London.9 Such stories were, however, given considerable popular credence, fed by a perception that Britain was losing the naval arms race with Germany.

Formation of the Camden Town Group

This social restlessness and volatility encouraged cultural change, and challenges to prevailing mainstream aesthetic values; it was against this background that the Camden Town Group was formed. Emerging from Gatti’s restaurant into Regent Street one Saturday night in spring 1911, Walter Sickert turned to his companions, held wide his arm and pronounced theatrically: ‘We have just made history.’ He had spent a bibulous evening with Harold Gilman, Spencer Gore, Robert Bevan and Charles Ginner lengthily discussing the idea of forming a new art exhibiting society. ‘We had indulged in a good dinner with abundance of wine to wash it down’, Ginner recalled; ‘Gilman was jubilant’.10 Debate continued the following week at 19 Fitzroy Street, where Sickert and a wider group of invited, sympathetic painters had been showing their paintings in rented rooms every Saturday (fig.2), and this was followed by ‘A second, slightly larger meeting’, Ginner tells us, that ‘took place at the Criterion’, another rather smart restaurant on Piccadilly Circus: ‘Here the new society could be said to have been safely launched, with the names finally decided of several artists to be invited.’11 Evidently it was a matter of fitting in, and ‘names’ were a topic of extended and detailed discussion. Invitations derived from this list ‘resulted in a full meeting held at yet a third restaurant, this time in Golden Square’ and it was here that Sickert ‘was responsible for the christening of this new venture as “The Camden Town Group”. Spencer Gore was elected President and J.B. Manson Secretary’.12 This convivial democratic birth process hatched a society of sixteen elected members: Walter Bayes (1869–1956), Robert Bevan (1865–1925), Malcolm Drummond (1880–1945), Harold Gilman (1876–1919), Charles Ginner (1878–1952), Spencer Gore (1878–1914), James Dickson Innes (1887–1914), Augustus John (1878–1961), Henry Lamb (1883–1960), Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957), Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot (1886–1911), James Bolivar Manson (1879–1945), Lucien Pissarro (1863–1944), William Ratcliffe (1870–1955), Walter Sickert (1860–1942) and John Doman Turner (c.1870–1938). Duncan Grant (1885–1978) joined the Group after their first exhibition, following Lightfoot’s resignation.

Camden Town painting was nurtured at the Saturday afternoon gatherings at Fitzroy Street. It represented a distinct tendency within a slightly wider selection of artists that Sickert invited to be a part of what was termed the Fitzroy Street Group, and who shared the rent of the premises. It was perhaps a natural consequence that this faction should form their own formal group. They continued to show their work at Fitzroy Street. The Saturday afternoons were social occasions, and tea was served by the Gores’ cleaner, who is commemorated in North London Girl (no.43). Louis Fergusson gave a flavour of what these occasions were like:

There was an appetising smell of tea and pigment as you ascended to a glorious afternoon of pictures and talk. Easels and chairs faced the fireplace with a serried stack of canvases against the wall. Six works or more of an individual painter were extricated in turn, each Fitzroyalist displaying his quota or having it displayed for him by the untiring Gore.13

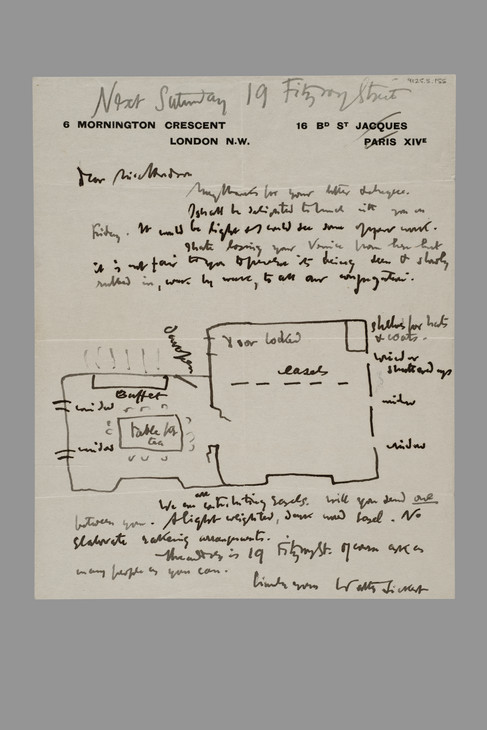

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Letter to Anna Hope (Nan) Hudson 1907

Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.155

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Letter to Anna Hope (Nan) Hudson 1907

Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.155

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert

4 ? st.[orey] apartments. ‘The heart of foreign club land’. Some gambling & some respectable clubs. ‘Foreigners are directed to these clubs by their consuls; that is why foreigners drift this way.’ Fitzroy Club at east side of doubtful respectability.18

Setting up the space at Fitzroy Street had been Sickert’s idea, and he had clear ideas about its purpose: ‘I want to keep up an incessant proselytizing agency to accustom people to mine and other painters’ work of a modern character’, he wrote to his friend Nan Hudson, ‘I want to create a Salon d’automne milieu in London.’19 But from the start, Sickert was alive to the business potential of the enterprise, and summarised his intentions:

Accustom people weekly to see work in a different notation from the current English one. Make it clear that we all have work for sale at prices that people of moderate means could afford. (That a picture costs less than a supper at the Savoy) Make known the work of painters who are producing ripe work, but who are still elbowed or kept out by timidity &c ... And of course no one will feel we are jumping at the throats to buy. That comes of its own accord. People pay attention to things seen constantly and judiciously explained a little.20

Writing again to Nan Hudson, he was even more candid about the type of customer he was hoping to attract to Fitzroy Street:

I want (& this we can all understand and never say) to get together a milieu rich or poor, refined or even to some extent vulgar, which is interested in painting & in the things of the intelligence, & which has not ... an aggressively anti-moral attitude. To put it on the lowest grounds, it interferes with business.21

According to Walter Bayes, it was Sickert who came up with the name for the Camden Town Group, ‘averring that that district had been so watered with his tears that something important must sooner or later spring from its soil.’22 It was where Sickert lived, at 6 Mornington Crescent, and where he kept up many simultaneous studios and addresses, among them his art school at Rowlandson House, 140 Hampstead Road; his etching studio at 31 Augustus Street; another address at 247 Hampstead Road; and a further studio in Brecknock Road. Camden Town was an area he was bound up in, and judging by the number of studios and lodgings he had there at any one time, an area with which he consciously associated himself. A number of the other Group members lived nearby and added logic to the name. Gore lived a few doors further down Mornington Crescent at number 31, where from 1909–12 he lodged with the local vicar, Andrew Osmond Archer. After his marriage he moved to Houghton Place, near the vast railway cutting for lines snaking out of Euston. Bevan lived at 14 Adamson Road, just beyond Swiss Cottage Tube, and Manson was two streets away at 184 Adelaide Road. For part of the life of the Group Gilman lived at 57 Harrington Street, just south of Mornington Crescent, but later moved out of London to Letchworth. Others had no connection with the area: Lucien Pissarro was at Stamford Brook, Malcolm Drummond and Charles Ginner both lived in Chelsea, and William Ratcliffe was in Letchworth.

While it was a part of North London where several of the artists lived, naming the Group after this area intentionally suggested a particular identity. Camden Town was a district associated with shabbiness, transience, urban decline, and was a socially diverse location where different classes were forced to mix together. These were characteristics that were to form the setting or subject for paintings by Sickert, Gore, Gilman and Bevan. Where Gore and Sickert lived in Mornington Crescent had originally been quite a smart street, and in the nineteenth century had been a sought after address for artists and writers: the painter William Clarkson Stanfield (1793–1867) lived at number 36 from 1834 to 1841, Frederick Richard Pickersgill (1820–1900) succeeded him in the same house, and George Cruikshank (1792–1878) lived round the corner at 48 Mornington Place.23 But by the time of the formation of the Camden Town Group it had become a somewhat less affluent area. As early as 28 October 1898 Charles Booth inspected Sickert and Gore’s street for his London poverty survey, and recorded in his notebook: ‘Mornington Crescent – of substantial 4 storey houses still probably exclusively of middle class but going down and now largely let in apartments.’24 Booth coloured the street red on his Maps Descriptive of London Poverty (1898–9), indicating the second most affluent level in his system of categorisation, and described as ‘Middle class. Well-to-do’. But in the final edition of his Life and Labour of the People in London (1902) he explained his system of categorisation further and detailed red as ‘Lower middle class. Shopkeepers and small employers, clerks and subordinate professional men. A hardworking sober, energetic class.’25

Group identity

In defining themselves as at variance with the old-fashioned painting of the Royal Academy or the New English Art Club, which had started to reject their pictures, the Camden Town Group were claiming a position of originality and innovation. But in reality they were also rejecting certain more adventurous developments that were then beginning to be felt, visible in the work of Wyndham Lewis and others. Ginner described how it was the aim of the new society to collect ‘a group which was to hold within a fixed and limited circle those painters whom they considered to be the best and most promising of the day’.26 This was quite evidently a value judgment, and essentially an ideological position.

Ginner claimed the other unifying factor was that ‘they had aspirations and held artistic ideals which they desired to bring to the notice of the art-loving public’.27 This slightly bland statement stems inevitably from the diverse character of the artists who they collectively agreed to be ‘the best’. Evidently they did not all hold quite the same ‘artistic ideals’; the work of the central group of colourists – Gore, Gilman, Ginner and Bevan – looked very different to that of Sickert, and all now varied from the pure traditional impressionism of Pissarro. Manson wrote in 1913 that the Camden Town Group ‘represented a coherent homogeneous school of expression; differing in degree as to the work of individual members, but with the unity of a common aim’.28 But at the first exhibition of the Group together in June 1911, many of the critics remarked on how different the artists appeared to one another, and noted a lack of unity of expression and subject. How then can we speak of a distinctive Camden Town style? The answer comes from the list of names present at the first proposal of the Group at Gatti’s, and the ones that Ginner picks out – Sickert, Gilman, Gore, Bevan and himself. They were the inner circle who, together with one or two others, perhaps Drummond and Ratcliffe, genuinely shared certain beliefs about a vigorous urban subject matter, if not always the manner in which it should be painted. There is a distinct difference between ‘Camden Town painting’ and the Camden Town Group, and certain fellow travellers such as Augustus John or Henry Lamb had no connection with the London-based subject matter of the Group’s progenitors. John only showed at the very first Group show, sending two Welsh landscape studies. It is likely he accepted election partly as an opportunity to see how his pictures sold and probably also as a favour to bring attention to the new endeavour, for by 1911 he was a well known and successful figure in the London art world. Lamb diligently showed at all three of the Group’s shows, but sent a trio of Breton figure subjects to the first exhibition and a pair of portrait studies to each of the two following. Lewis was the most out of kilter; at the first Camden Town show he exhibited two angular figure studies, The Architect (No.1) and The Architect (No.2), at the second a group of three works (now lost) described by the Times as ‘geometrical experiments’,29 and at the last his cubist painting Danse, also lost. He was the focus for the critics’ ire on each occasion, and was even denigrated in print by Manson, who in response to the ‘geometrical experiments’ in the second exhibition described Lewis’s drawing as ‘untrue and distorted, and therefore bad’ because ‘if they are meant to represent life in some way, they must be built up on a fundamental basis of Nature’. Compounding an already insulting review, Manson dismissed Lewis’s work as more suitable as designs for ‘a fin-de-siècle carpet’.30 Even one of the exhibitors felt he did not belong: Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot seems to have been embarrassed by his own inclusion in the first exhibition, claiming in a letter to his friend from Slade days Rudolph Ihlee that he had never really been a member and rubbishing the contributions of Gore, John and Lamb:

The Camden Town Group are holding their exhibition at Carfax. It’s about the worst show I ever seen [sic] in my life ... I suppose you know they drew me in to be a member of the Group, without my consent by the way ... I swear on my oath I will never show with the crowd again. It is 19 Fitzroy Street to the core. My stuff looks as much out of place and absurd as I do when I go to the Saturday afternoon lying competition at Sickert’s [ie. the displays of work at 19 Fitzroy Street]. They have had no money from me – and I’ll take it a good care they never will.31

The business of painting

As much as ideological or practical, the motivation for setting up the Camden Town Group was economic. Its formation coincided with the fallout from Roger Fry’s 1910–11 exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists. This had brought modern French art to a wider English audience for the first time, and the show included the work of Edouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck. The press had a field day in pouring scorn on what they characterised variously as childish, primitive, immoral and bad.32 There was a certain amount of position taking, and one consequence was a conservative backlash as to what got accepted for exhibition – and therefore sale – at the New English Art Club. Founded in 1884 the NEAC had formerly been the crucible for the showing of new and adventurous British art. Sickert had staged a coup at the end of the 1880s to force it towards impressionism, and continued as a stalwart of its organising committee. But by 1910 the NEAC had become a more conservative body, which was ironic, as it had been formed in response to the reactionary character of the Royal Academy. By 1913 the Times could describe the NEAC as ‘one of the strongest conservative forces in the country. What was an adventure has become an institution.’33 Certain members of the Fitzroy Street group, notably Gilman, had found it difficult to have their work accepted before 1910, but around this date there was a certain relaxation in attitude and their pictures started to be accepted more easily. But with the fallout from Manet and the Post-Impressionists came the realisation that positions on progressive art were polarising and that as a vehicle for invention the NEAC was limited. The NEAC leadership of Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer came out bitterly against Fry’s show, and they were aided by the critic D.S. MacColl, whose denunciations in print became a focus for reaction. This too was ironic, for MacColl had been a passionate advocate of impressionist painting in the closing years of the nineteenth century, but now would not support what came after it.

By the 1910 NEAC winter exhibition, Gore was able to write to his student John Doman Turner:

Your drawings looked very distinguished when they came up at the NEAC. Unfortunately the most conventional minded of a set of people whose ideas of painting are about 50 years out of date hung the watercolours of [Alfred] Rich!!! ... his work ... is entirely imitative and has not an atom of observation in it ... Also you may notice that we – myself, Pissarro, Gilman, Bevan, Lamb have all been gently pushed into the inner rooms. Gilman had one thing rejected and Bevan two water colours while Innes another interesting artist has all his watercolours very badly hung.34

In his next letter to Doman Turner, Gore wrote even more baldly:

As to where things are hung it means nothing except that the NEAC dislike our kind of painting and will probably edge us out all together sooner or later and you have suffered with us.35

Gilman bitterly resented any failure to get his paintings accepted at the NEAC, and he saw a breakaway group as the only solution. ‘Something had to be done’, Ginner wrote retrospectively of Gilman’s mindset, ‘and when possessed with the idea that some wrong needed redressing he was not one to let the matter rest until something had been done’.36 The critic Frank Rutter wrote that discussions as to whether to try to take over the NEAC or form a new group altogether went back to 1908, and that at Fitzroy Street Sickert argued a different way each week.37

In hampering exhibition of the Camden Town painters’ work, the NEAC was also restricting their ability to make money. Opportunities for artists to show their work in London were quite limited, and for progressive artists it was particularly difficult. The practice of holding Saturday afternoon open house at Fitzroy Street when each member could show their work was a blow for economic freedom. It meant they were not beholden to dealers or to the commission a dealer would charge. They could form direct relationships with collectors, which would be good for business and might result in commissions. By controlling access to their sales there were clear advantages and potential savings to the purchaser from buying directly; any discount from the artists not paying a dealer’s commission could be passed on to the buyer, potentially making their work competitively cheaper. Sickert with his flair for publicity and innate appreciation of the economic realities of painting realised that the formation of a formal Group would bring critical attention, and the securing of an exhibition an opportunity to maximise sales. However, the reality is that there appears to have been relatively few individuals who bought the Camden Town Group’s work in numbers at the Saturday afternoon showings, and much seems to have gone unsold. Arthur Clifton at the Carfax Gallery in Bury Street appears to have been swayed by Sickert’s cast iron belief in the Group’s potential and gave them three showings between 1911 and 1912. But he eventually withdrew, evidently disappointed by the financial success of the exhibitions.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Evening, Dieppe 1911

Oil on canvas

610 x 463 mm

Private collection, by courtesy of MacConnal-Mason Gallery

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © MacConnal-Mason Gallery

Fig.4

Charles Ginner

Evening, Dieppe 1911

Private collection, by courtesy of MacConnal-Mason Gallery

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © MacConnal-Mason Gallery

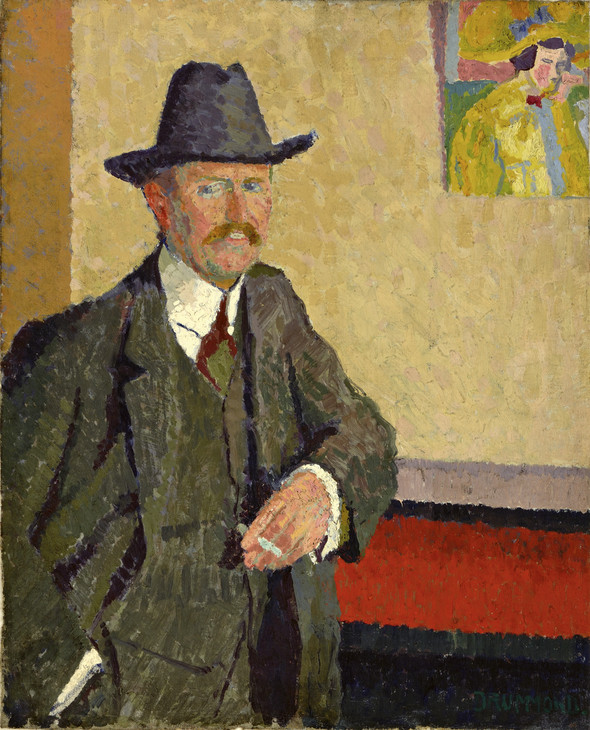

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Charles Ginner 1911

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 490 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.5

Malcolm Drummond

Charles Ginner 1911

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

The prices the Camden Town Group asked for their pictures at the exhibitions were relatively modest. The June 1911 exhibition did not print prices in the catalogue, but the following two shows did. In December 1911 a Gilman nude was 25 guineas and Ginner’s Evening, Dieppe (fig.4) the same price, but sold to Mrs Fox-Pitt for 20 guineas;38 Drummond’s portrait of Ginner (fig.5) was 20 guineas; Bevan’s The Cabyard, Night (fig.6), one of the most expensive works in the show, was 35 guineas; Ratcliffe’s four pictures were more modestly priced at either 8 or 10 guineas. Sickert’s works were grandly marked in the catalogue ‘Prices on application’. The December 1912 exhibition followed a similar price range. Ratcliffe now wanted either 10 or 15 guineas for his four pictures, Drummond asked 20 guineas for Brompton Oratory (fig.7), Ginner 35 guineas for Piccadilly Circus (fig.8), Gore either 20 or 25 guineas for his contributions, and Bevan just 15 guineas for A Devonshire Farm but 35 guineas for The Horse Mart (one of the biggest pictures he ever made). At 60 guineas Sickert’s Summer in Naples (or Dawn, Camden Town) was the most expensive picture in the show by a large jump.39 Nor were these necessarily the prices realised when a sale was clinched; Ginner’s Sunlit Quay was on offer for 30 guineas in December 1911, but he ended up selling it for just £7.40

Robert Bevan 1865–1925

The Cabyard, Night 1910

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 690 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.6

Robert Bevan

The Cabyard, Night 1910

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

1908 £4-0-0 1913 £24-6-0 1918 £248-12-0

1909 £27-1-0 1914 £109-2-3 1919 £480-7-0

1910 nil 1915 £67-5-0 1920 £405-13-0

1911 £94-7-0 1916 £44-5-0 1921 £139-10-0

1912 £54-8-0 1917 £79-11-0 1922 £306-10-0

1909 £27-1-0 1914 £109-2-3 1919 £480-7-0

1910 nil 1915 £67-5-0 1920 £405-13-0

1911 £94-7-0 1916 £44-5-0 1921 £139-10-0

1912 £54-8-0 1917 £79-11-0 1922 £306-10-0

Ginner’s first year in England was 1910, and although he exhibited at the Allied Artists’ Association he did not have any sales. Until the end of the Great War the amounts are pitifully low. Ginner would have earned more as a clerk than he did from painting. To put it in bleak perspective, when B. Seebohm Rowntree made his survey of York’s working classes in 1899, he calculated that a subsistence income with no meat for a family with three children was 21s 8d a week, and this he classed as poverty.42 Although he was single, Ginner’s income in 1913 was less than this. In 1907 an agricultural labourer in London or the Home Counties could expect to earn 18s 7d a week, around £50 a year.43 Ginner’s breakthrough came during the War. In 1918 he was commissioned to paint the vast ten by eleven foot No.14 Filling Station, Hereford for the Canadian War Record, and was paid £350 plus living expenses, received in 1919. But this was an unusual event. He sold The Blouse Factory 1917 for just £2. In the whole of the period listed above Ginner earnt £2,088. In the same period, William Orpen, born the same year as Ginner in 1878, a New English Art Club exhibitor and a fellow Slade student with Gore and Gilman received a total of £168,316 from his painting.44 It is an extreme example, as Orpen was probably the most successful painter in Britain at this time, but it is nevertheless instructive.

There are also records of Gore’s income between 1905 and 1913:45

1905 £28-0-0 1908 £113-12-0 1911 £205-0-0

1906 £15-0-0 1909 £127-0-0 1912 £284-2-0

1907 £99-18-0 1910 £162-6-6 1913 £195-0-0

1906 £15-0-0 1909 £127-0-0 1912 £284-2-0

1907 £99-18-0 1910 £162-6-6 1913 £195-0-0

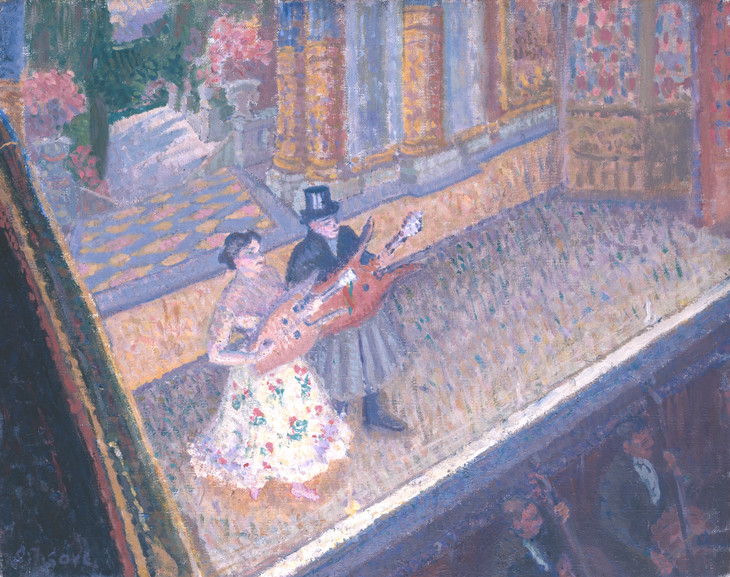

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Inez and Taki 1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 406 x 508 mm; frame: 608 x 710 x 52 mm

Tate N05859

Purchased 1948

Fig.7

Spencer Gore

Inez and Taki 1910

Tate N05859

Colour: a critical response

Critical reaction to the Group’s shows was mixed, but none was excessively hostile.49 Writing of the launch exhibition the Daily Graphic noted sardonically:

It cannot be said there is anything among the exhibits which calls for a lyrical expression of delight, unless such might be inspired by a company of ballet dancers, cab horses, and murderers, to which Mr. Gore, Mr. Bevan and Mr. Sickert introduce us.50

Under the heading ‘Art Anarchists’, the Morning Leader felt it necessary to warn visitors:

Certain pictures, the ‘Crocks’ and ‘Cab Horse’ of Mr. R.P. Bevan, for instance, will come as a shock to those accustomed to traditional methods. Mr. Bevan’s work at first sight looks as if a naughty child had run amok with a box of crayons and a badly illustrated paper ... for looking at a few of the pictures in the exhibition smoked glasses are almost a necessity.51

The bright, pure colours of Gore, Gilman and Bevan were a concern to many of the reviewers, and this aspect of their work had already been noted at showings shortly before. Huntley Carter in the New Age identified a small group of ‘colourists’ within the 1910 New English Art Club exhibition. He noted that colour had the potential to enervate and be a source of disturbance, and that ‘three fourths of the human race are unaffected by colour, except in a hostile form. Pure, clean colour arouses in their honest bosoms an exasperation only equalled by that called forth by the so-called indecent forms of art.’ Turning to the exhibition, Carter continued:

The successful praise of colour, which is one of the highest achievements in painting, has been undertaken and accomplished by a small group of painters. Within this group there is another small group composed of painters who intimately understand the colour of colour and the colour of shadows. One who has mastered this knowledge is S.F. Gore ... Another is Lucien Pissarro, who is carrying on the brilliant traditions of his father ... Robert Bevan is a third colourist belonging to this individual group. Here, again, in his work are clear vision and clever interpretation, light and colour treated reverently and handled sincerely, and with full understanding ... A fourth is Harold Gilman ... I have grouped these four painters because their work has characteristics in common. They do not seek to uphold the academic traditions of the N.E.A.C. ... They conceive and express subject in colour; they work putting the colour on in separate touches all through; they use very simple palettes and make very simple mixtures. They avoid the use of varnishes; their surfaces are, in consequence, matt, and thus their work largely partakes of the character of early tempera.52

Carter was right to identify a group of colourists, and it is this colourist cadre of Gilman, Ginner, Gore and Bevan who were the most advanced members of the Camden Town Group. Sickert, despite a brief flirtation with a heightened palette, somewhat disapproved, and after the dissolution of the Group became aggressive in his dismissal of the use of brilliant colour. Gilman had been under his mentorship, painting smoothly in creams, tans and browns. But his exposure to van Gogh and Cézanne at the post-impressionist exhibition made him begin to change direction. Under Ginner’s partial influence, Gilman began to extend his palette. In late 1910 or early 1911 with Ginner and Frank Rutter he visited Paris to see impressionist and post-impressionist pictures. Ginner recalled how they looked at

collections such as Bernheim’s, who possessed a room entirely decorated with the works of Van Gogh, a sight unsurpassed in beauty and intensity; Durand Ruel’s collection of French Impressionists; Pellerin’s Cézannes; also the Vollard and Sagot Galleries with their Rousseaus, Picassos, Vuillards, etc.53

But Ginner noted that Gilman

did not immediately accept van Gogh, and I can remember a long argument we had on the merits of this master. It was interesting to see that he slowly developed an intense admiration for van Gogh, and came to look upon him as the greatest of the group of painters, Cézanne, Gauguin, etc., with which the Dutchman is associated. Gauguin, whom he at first believed in most, he considered too aesthetic and classic in spirit, though he always admired his amazing variety of design.54

Wyndham Lewis wrote amusingly but with psychological accuracy about how once this change had occurred, Gilman could no longer countenance Sickert’s sombre colours:

A slight shudder would convulse him as the thought of the little worm of brown paint that was possibly, even at that moment, wriggling out onto the palette that held no golden chromes, no emerald greens, vermilions, only, as it, of course, should do. Sickert’s commerce with these condemned browns was as compromising as intercourse with a proscribed vagrant ... bituminous painting, dirty painting, was the mark of the devil ... But he always retained a great respect for the virtues of his first real master.55

Although Gore had already begun to evolve a new palette by 1910, for him it was Gauguin and Matisse who held the greatest interest in Fry’s show. Gore’s rhythm of patterns, his strong, vibrant colour harmony and his unusual, oblique viewpoints in paintings of the music hall set a standard that was to extend rapidly to the simplified, angular forms of his pictures of Letchworth. But while Gore, Gilman and others assimilated continental aesthetics, there was always present a consciously native subject-matter, be it the dusty streets and interiors of north London or the occasional native quirkiness of certain subjects.

Tension and dissolution

There were from the beginning two related issues that contained the seeds of the Group’s eventual disintegration – the expansion of the Group to take on new members of a more progressive kind, and whether women should be allowed to be members. At a time when the suffragette campaign was reaching new heights, it may seem surprising that a group of progressive artists should exclude women. Their motive appears to have been to avoid the embarrassment of some of the male members requesting that their painter wives or friends be included. Ginner recorded:

Gilman, strongly supported by Sickert, was in full opposition to such a proposal as he contended that some members might desire, perhaps even under pressure, to bring in their wives or lady friends and this might make things rather uncomfortable between certain of the elect, for these wives or lady friends might not quite come up to the standard aimed at by the group.56

Manson claimed in a private letter to Pissarro’s wife Esther, who was pressing him energetically to accept her friend Diana White, that it was designed to exclude Sickert’s painter friends Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson.57 Sickert himself wrote bluntly to the pair:

As you probably know, the Camden Town Group is a male club, & women are not eligible. There are lots of 2 sex clubs, & several one sex clubs, & this is one of them.58

At a formal meeting of the Group on 2 December 1911 there was a debate on expansion, which implicitly involved including more progressive artists. Manson recorded in his hastily written notes:

Sickert opened the proceedings by proposing that one black ball should exclude candidates from membership. This was not seconded. Sickert then invited members to express opinions as to whether the group should be enlarged or kept a closed group. He himself being in favour of a closed society. Mr Gilman said he would like to elect all men whose work was interesting to the group. Lamb, Ginner and Lewis were in favour of increasing the number of members ... Mr Bevan was in favour of enlarging the society. Mr Pissarro ditto. Provided that care was taken the work of proposed members was strictly in accordance with the aims of the group.59

There was a feeling – rightly – that if the Group expanded, its character and focus would inevitably change. The issue was shelved until a larger exhibition space to accommodate an expanded group was found.

Even at the jubilant meeting that launched the Camden Town Group, whether certain truly advanced artists should be allowed to be included was a source of dissension:

There was one point that still remained unsettled and this was the question of the election of Wyndham Lewis, whose name had caused much opposition in certain quarters of the group, as he was at that period touching the fringe of cubism, anathema to certain of the members. But they had to reckon with Gilman who was determined that Wyndham Lewis should be one of the select few, with the result, almost foreseen, that he was duly elected.60

Gore too was a passionate supporter of Lewis, with whom he had been a close friend since their days at the Slade School of Art. But most importantly he believed wholeheartedly in the plurality of modernisation that was taking place in British art. Others such as Pissarro wanted only to maintain impressionism – a phenomenon in France of forty years before – as the focus for the Group. Pissarro, with Sickert too if he was honest with himself, disliked the proto-cubism of Lewis and the advanced art of others around him such as David Bomberg (fig.8), but now inevitably they looked set to join them.

The London Group

In the wake of Roger Fry’s more extreme second post-impressionist exhibition in 1912–13, resistance to recognising radical tendencies in London became untenable. The Camden Town Group and a now expanded Fitzroy circle were in 1913 combined to form a new and more diverse exhibiting society, complete with advanced elements. As Manson explained it to an intransigent Pissarro:

I feel that in denying these new movements a right to express themselves, we should be acting exactly as the Academicians did with regard the Impressionists and precisely as the N.E.A.C does ... I feel the other attitude of intoleration is rather narrow. I don’t think we have any reason to be afraid of a few extreme young men; nor ought we to run away from them.61

Pissarro replied:

What I object to is that it is the wrong clique that has gained influence ... Fancy people joining with the idea of forming a teetotaller society and coming to the conclusion that in order not to be narrow minded, they should admit some drunkards!62

The London Group was founded in November 1913, with Gilman as its President, and was an amalgam of the sculptors Epstein and Gaudier-Brzeska, Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticists and Futurists, and the Camden Town Group. They first exhibited together in Brighton in November 1913. Although Sickert showed in the exhibition, and gave the opening address, he resigned in January 1914, explaining to Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson:

Like the lady in bridal attire who bolts at the church door the Epstein-Lewis marriage is too much for me & I have bolted. I have resigned both Fitzroy Street and the London Group ... At Brighton the Epstein-Lewis-Etchells room made me sick ... On Saturday Epstein’s so-called drawings were put up on easels and Lewis’s big Brighton picture. The Epsteins are pure pornography – of the most joyless kind suit- dit & the Lewis’s pure impudence ... never again for an hour would I be responsible or associated in any way with showing such things. I don’t believe in them, and, further, I think they render any consideration of serious painting impossible. I hope you don’t think my conduct, to Gore & Gilman chiefly, cowardly or treacherous. You know they have dragged me step by step in a direction I didn’t like, & it was only a question of the exact date of my revolt. It is, after all, they who believed in this thing & I who suffered it to please them ... Bevan admits that Fitzroy Street shall be dropped when the lease is out in March. I shall not set foot in it again ...63

Turning his attention to art criticism, Sickert used his weekly column in the New Age to promulgate his beliefs about the direction new British art should take. But in doing so he ended up attacking two of his Camden Town Group colleagues, Ginner and Gilman, who now termed themselves neo-realists. In June 1914 Sickert reviewed the New English Art Club exhibition and praised Henry Lamb lavishly as a painter who did not lean towards certain practices:

He has never been, for a moment, the dupe of technical pedantries. He knows, for instance, that it is a trivial thing to spend a life-time in an effort after intrinsic brightness of paint. He knows that the brightest colours will fade. He knows that there is a strict limit to the advantages of impasto. He knows that, firstly, excessive impasto is not even durable. He knows that impasto is not in itself a sign of virility. Intentional and rugged impasto ... is a manner of shouting and gesticulating and does not make for expressiveness or lucidity.64

With justification, Gilman felt this was thinly veiled criticism of his and Ginner’s work. Sickert’s claim that heavy impasto was ‘not even durable’ and that bright colours faded struck deeply at Gilman’s ability to sell his work, implying to potential buyers that it would degrade. The next issue of the New Age printed Gilman’s letter of complaint, under the headline ‘The Worst Critic in London’, although this is likely to have been phrased by the journal rather than Gilman. ‘In making a catalogue of all the things that Mr Lamb knows’, Gilman wrote,

tending to show that that gentleman is not an idiot, seems to imply that there is someone – presumably exhibiting at the NEAC – who does not know those things ... I am not acquainted with any man who thinks there is any merit in thick paint for the sake of thick paint. Mr Sickert has himself painted in both thick and thin paint. This violent paragraph of his may be merely his way of expressing his preference for thin. He will be painting in thick paint in six months. It is in any case, a technical detail, and depends on the questions of brilliance, permanence, covering power, deliberateness of workmanship, etc., impossible to discuss here ... I wonder if this row of teachers of Art is set up by Mr Sickert to be an easier mark for his inevitable cockshies at any society from which he has retired.65

Charles Ginner expressed himself more succinctly, in a letter printed below Gilman’s:

Sir, Paint is thicker than turpentine. In answer to Mr Sickert I have but one statement to make: I shall paint as thick as I damn well please.66

Sickert’s riposte was to imply in a further piece that Gilman and Ginner were pricked by not being mentioned in his review, and he titled the article ‘The Thickest Painters in London’, a double-entendre quite clearly intended to heap mockery upon them. ‘They talk a good deal about Cézanne,’ Sickert wrote patronisingly:

I admire what is good in Cézanne perhaps as much as they do. But I think I have looked at him more carefully ... Will they not look at the Gores in the New English Art Club and say whether that skilful, delicate, draughtsmanlike, reticent use of thick paint, that eloquent variety of touch, is not an ideal technique?67

Sickert caused considerable ill feeling in this attack on his former Camden Town colleagues, and others of the circle such as Harold Harrison of Applehayes,68 Hugh Blaker69 and Douglas Fox-Pitt wrote in to the New Age: ‘I feel sure Mr Sickert will not be hurt’, Fox-Pitt wrote, ‘when I say that posterity will know him as a great painter and not as an art critic ... People of taste will always be thankful to Mr Sickert for having founded the Camden Town group.’70

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Tipperary 1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 600 x 500 x 55 mm

Tate N05092

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

© Tate

Fig.9

Walter Richard Sickert

Tipperary 1914

Tate N05092

© Tate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Brighton Pierrots 1915

Oil paint on canvas

unconfirmed: 635 x 762 mm; frame: 901 x 1030 x 120 mm

Tate T07041

Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1996

© Tate

Fig.10

Walter Richard Sickert

Brighton Pierrots 1915

Tate T07041

© Tate

These lunges and parries were conducted just weeks before the outbreak of the First World War, after which such nuances would seem inconsequential. The War marked a sharp dividing line for the painters who had formed the Camden Town Group. Gore died in April 1914 having caught pneumonia painting in Richmond Park; he was thirty-five. Gilman spent the War in London, exempted from military service by his club foot. Painted after the shock casualties of the Somme, his pictures of Mrs Mounter (fig.2) staring ambiguously back at us seem inextricably tinged with the melancholy and mourning of the world beyond these interiors. Being an un-uniformed man in London, not engaged in helping the war effort, questions must have been raised in Gilman’s mind about the role of the artist in society and his exclusion from what others were going through in the trenches. Sickert responded to the War with canvases that began with the plucky heroism of Belgian soldiers standing up to Germany, through the tinkling buoyancy of Tipperary (fig.9) to the weird disjunction of a group of Pierrots playing to an almost empty row of deck chairs at Brighton (fig.10), the crump of artillery perhaps audible across the Channel. Ginner alone was briefly in uniform; in 1916 he was conscripted into the Royal Ordnance Corps, then transferred to Intelligence, before being taken up as an official war artist by the Canadians.71 Back in London, early in 1919 he contracted Spanish flu. Gilman went to nurse him, caught it himself, and died. The great city, an emblem of the modern world, can no longer have seemed a quite suitable subject. Lewis’s premonition of it as an alienating, unstoppable, violently dehumanising force had become all too recognisable in the carnage of the trenches.

Notes

Walter Sickert, ‘Impressionism’, preface to A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, December 1889, in Anna Greutzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.60.

See Richard Shone, ‘Text and Image: Camden Town Painting and Contemporary Fiction, in Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008, pp.44–5.

See Robert Upstone, ‘The London Context and Critical Reception of Robert Bevan’s “The Cab Horse” (1910)’, Burlington Magazine, October 2007, pp.689–93.

Art in Britain 1890–1940 from the Collection of the University of Hull, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull, February–March 1967, p.61.

Art in Britain 1890–1940 from the Collection of the University of Hull, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull, February–1967, p.60.

Notebook B355, pp.87, 129, Booth Collection, Archives of British Library of Political and Economic Science, London School of Economics. Booth’s parentheses indicate the comments of the police officer.

Notebook B357, p.25, Booth Collection, Archives of British Library of Political and Economic Science, London School of Economics.

James Bolivar Manson, Introduction to the catalogue of the exhibition English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Brighton Art Gallery, December 1913–January 1914.

Letter from Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot to Rudolph Ihlee, June or July 1911; quoted in Rudolph Ihlee 1883–1968, exhibition catalogue, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, August– September 1978, p.12.

See Anna Gruetzner Robins, Modern Art In Britain 1910–1914, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1997.

See the catalogues to The Second Exhibition of the Camden Town Group, Carfax Gallery, December 1911, and The Third Exhibition of the Camden Town Group, Carfax Gallery, December 1912.

See Roderick Floud and Paul Johnson (eds.), The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain: Volume I: Economic Maturity 1860–1939, p.51.

In Gore’s records five pictures are listed, although the limit for each exhibitor was four. Two are Mornington Crescent subjects, one selling to Somerset Maugham, and it seems likely that this was then removed and its place taken by another.

Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’, Memorial Exhibition of Works by the late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London, October 1919, p.5.

See Art in Britain 1890–1940 from the Collection of the University of Hull, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull 1967, p.66.

Letter from Walter Sickert to Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson, June 1911; Tate Gallery Archive, 9125/5 (77).

Meeting of the Camden Town Group, 19 Fitzroy Street, 2 December 1911; Tate Gallery Archive, 806/10/1.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New English Art Club’, New Age, 4 June 1912, p.115; Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, pp.374–5.

Acknowledgements

This essay was first published in Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate 2008.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Painters of Modern Life: The Camden Town Group’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www