Malcolm Drummond Girl with Palmettes c.1914

Malcolm Drummond,

Girl with Palmettes

c.1914

A woman in a broad-brimmed hat and tailored coat stares intently at the viewer from the shallow space of Drummond’s painting, rendered in thick layers and bright post-impressionist colours. The distinctive palm leaf motif on the wall has not been linked to a known interior. New evidence suggests the sitter may be Drummond’s first wife, Zina Ogilvie.

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Girl with Palmettes; ?Portrait of the Artist’s Wife

c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

498 x 403 mm

Purchased with funds provided by the bequest of Florence Fox 1966

T00893

c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

498 x 403 mm

Purchased with funds provided by the bequest of Florence Fox 1966

T00893

Ownership history

Inherited by Margaret Drummond, the artist’s widow, 1945, by whom sold to Agnew & Sons Ltd., London, 1966; bought by Tate Gallery with funds provided by the bequest of Florence Fox 1966.

Exhibition history

1965

Malcolm Drummond, Bonfiglioli Gallery, Oxford, May 1965 (17).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (51, reproduced).

References

1967

Times, 20 March 1967, p.10 reproduced.

1976

Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976, pp.23–4.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.344–5, 364, reproduced pl.141.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.166.

Technique and condition

Girl with Palmettes; ?Portrait of the Artist’s Wife is painted in artists’ oil paints on a primed canvas that has subsequently been lined. The original canvas is plain-weave cloth, probably linen, with white priming. The lining was probably undertaken to flatten the brittle network of age cracks that have developed, perhaps owing to the leanness of the paint. No initial drawing is apparent and the painting appears to have been executed over an extended period of time. There are several thick layers of paint in most areas, the texture of the lower layers being retained during the application of new layers showing that they were at least touch dry. The layering of the paint reveals the evolution of the colour scheme as the intensity of tonal contrasts and the juxtaposition of complementary hues were heightened during painting. The colours are applied brusquely in largely one colour areas. The colour shapes often do not quite abut, leaving ragged borders in which underlying colours are visible. There are areas where the composition has been altered as with the reduction in size of the crown of the hat.

The surface has a general greyness from imbibed dirt that is especially apparent on the tops of impastos that are squashed and abraded as a result of the lining treatment. The surface dirt has reduced the starkness of the colour contrasts which are also softened by the white scatter produced by some crystalline efflorescence on the dark blue greys. This efflorescence is characteristic of the presence of ultramarine in the mixtures. The surface is unvarnished but has a slight waxy coating also from the lining.

Roy Perry

November 2003

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', November 2003, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Girl with Palmettes; ?Portrait of the Artist’s Wife c.1914 by Malcolm Drummond’, catalogue entry, April 2008, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

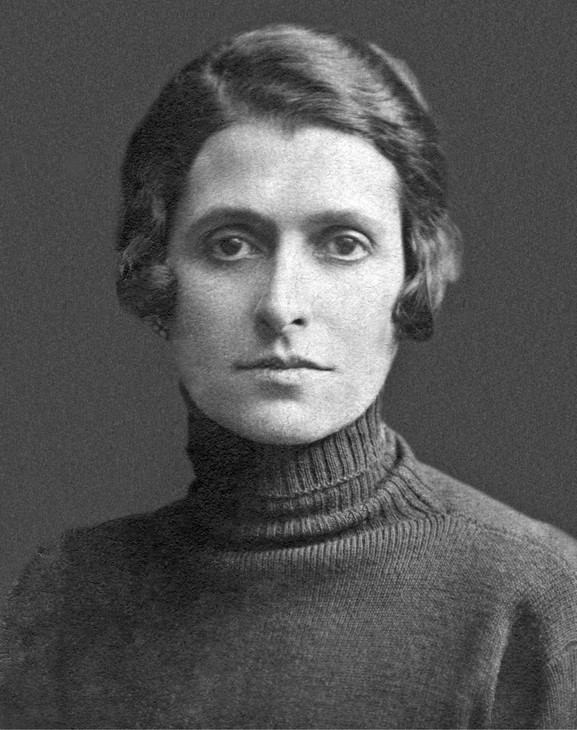

The title of Malcolm Drummond’s visually striking portrait, Girl with Palmettes, was not the artist’s own but one bestowed upon it by the art dealer, Kyril Bonfiglioli, for an exhibition of Drummond’s work in Oxford in 1965. The painting depicts the head and shoulders of a young woman wearing a broad-brimmed hat and a tailored coat with a pale frilled collar. She faces directly out of the painting at the viewer. Behind her is a cream-coloured wall upon which, just visible in the top right-hand corner of the painting hangs a framed and mounted picture. The identity of the ‘Girl’ had remained a mystery until recently, when descendants of the artist’s first wife, Zina Ogilvie (1887–1931), suggested that it represents a portrait of her.1 Comparison of photographs of Zina (figs.1 and 2) and another painting of her by Drummond reveal a certain facial similarity to the sitter.2

Zina Drummond c.1925

Courtesy of the McIntyre family

Fig.1

Zina Drummond c.1925

Courtesy of the McIntyre family

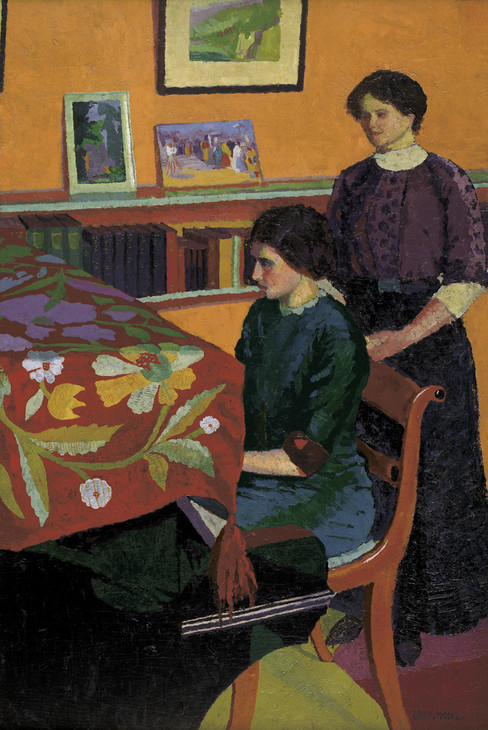

Bonfiglioli’s title draws attention to the most distinctive aspect of the work, the brightly coloured mural frieze, which is partially obscured by the head of the woman. A palmette is a decorative moulding or painting in the form of a stylised palm leaf. The visible portion of the frieze is composed of two large fan shaped palmette motifs linked by the representation of an animal, probably a lion, of which only the head and legs can be seen. The design appears to be painted on to the plaster of the wall in the manner of a stencil. Unfortunately, despite the distinctive appearance of the background, the setting for Girl with Palmettes has never been identified. It was not recognised by Drummond’s daughter from his first marriage, or the artist’s second wife, Margaret, who did, however, raise the suggestion that ‘the decorative motifs could have been in a “pub” in the neighbourhood of his studio in Yeoman’s Row, Chelsea’.3 A further possibility is that this design is part of an original and experimental scheme decorating a private, domestic room similar to that in another undated painting by Drummond, Interior (private collection).4 In this work the viewer looks through an open door to a passageway which is decorated with a horizontal frieze border characterised by repeated blocks of colour with a semi-circular fan-like motif. The setting in Interior is also unknown, but, furnished with a chair and an umbrella stand, it looks like the hallway of a house. Drummond’s interiors often contain visual references to artistic practice, either in the form of paintings hanging in the background or in the depiction of a particularly noticeable feature of the décor, such as the highly coloured floral cloth covering the grand piano in At the Piano c.1912 (fig.3), or the painted panels and glass lanterns of the Hammersmith Palais de Danse 1920 (Plymouth City Art Museum and Art Gallery).5

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

At the Piano c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

898 x 608 mm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 692P11. South Australian Government Grant 1969

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Fig.3

Malcolm Drummond

At the Piano c.1912

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 692P11. South Australian Government Grant 1969

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Both stylistically and thematically, Girl with Palmettes is a product of what the author and art historian Quentin Bell called Drummond’s ‘heroic period when he had seen the post-impressionists and was marching in step with Spencer Gore and Gilman’.7 Certain elements of technique and design demonstrate an assimilation of the ideas of other Camden Town Group members. For example, the use of green to describe the shadows of the face is particularly indicative of the art of Harold Gilman who used it to audacious effect in his later portraits, for example Sylvia Gosse 1913 (Southampton City Art Gallery).8 Also comparable to Gilman is the uniform texture of the painted surface and Drummond’s use of strong, bright colours and thick impasto across all of the canvas, treating the face and body of the figure with the same intensity as the decorative features and the plastered wall in the background. Juxtaposed patches of vivid turquoise, green, pink and orange at the base of the woman’s neck and underneath her left eye mirror the chromatic arrangement of the palmette frieze. This reveals an interest in colour and pattern most likely awakened by the work of Vincent van Gogh, and certainly shared with Ginner, Bevan and Gore, as well as Gilman’s practice of painting his sitters against a background of decorative wallpapers. The bold chromatic patchwork is perhaps also reminiscent of Henri Matisse’s famous portrait of his wife, La Raie Verte (known as The Green Stripe) 1905 (Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark).

The severity of the design of the painting is remarkable, with its flat background, narrow space and the uncompromising pose of the figure. Despite the woman’s frontal position the composition of the painting is not an exact balance between left and right around a central axis. The two palmettes are of different sizes, there is the prominent yellow and mauve framed picture mount in the right-hand corner, and, surprisingly, the woman’s mouth and nose are not centred on one another, as her lips are shifted to our right, away from the exact centre of her face. This may be to stabilise the strong illumination that comes from one side, and it is hardly noticeable until pointed out. The lighter side of her face is more prominent, and this is compensated by the larger palmette, especially as it is of the same colours, at the left.

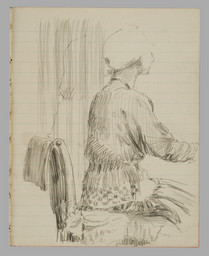

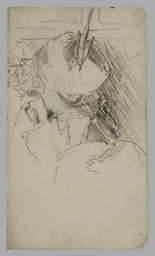

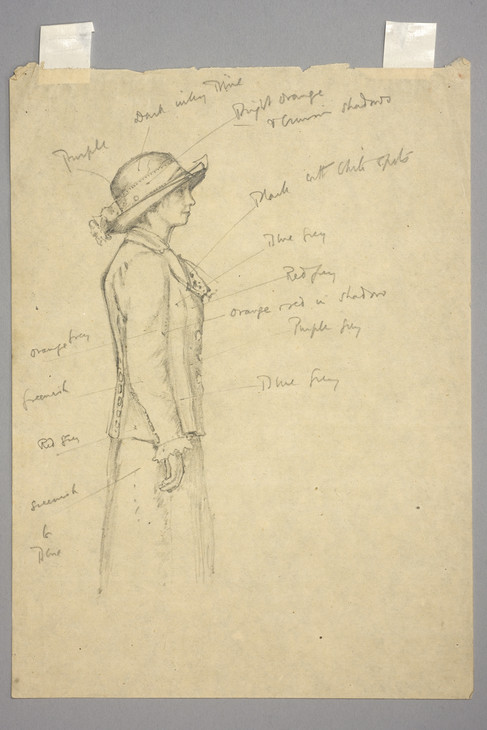

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

Study for 'Girl with Palmettes; ?Portrait of the Artist's Wife' c.1914

Graphite on paper

250 x 180 mm

Inscribed by the artist with various colour notes in pencil

Tate Archive TGA 8915

Purchased from Joyce Mills, September 1989

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Fig.4

Malcolm Drummond

Study for 'Girl with Palmettes; ?Portrait of the Artist's Wife' c.1914

Tate Archive TGA 8915

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

The only other evidence regarding Girl with Palmettes is that which can be inferred from the details of the sitter’s costume. The purple broad-brimmed asymmetrical hat with the wide orange band and the dark fitted jacket with slightly puffed sleeves and frilled collar seem to date from the period 1914–20 and resemble the respectable, although not particularly expensive or fashionable, clothes worn by a woman from the urban middle class.9 An undated pencil sketch from the artist’s estate, now in Tate Archive (fig.4), appears to be a drawing of the same figure in three-quarter length profile with annotated colour notes describing her clothing. The partially legible description of the hat as ‘Purple’ and ‘Dark inky blue’ with a wide ribbon band of ‘Bright orange | & crimson shadows’ corresponds with the appearance in Girl with Palmettes and suggests that this is a sketch associated with Tate’s painting. The drawing reveals the woman’s coat to be a waist-length tailored jacket buttoned at the front with further button detailing at the back, worn with a simple straight skirt. The material is described in the notes as variations of grey, green and blue, and is therefore a lighter colour than appears in the painting. Furthermore, in place of the pale frilled collar, the woman in the sketch wears at her neck a scarf described as ‘Black with white spots’, although she does have a white frilled cuff emerging from the sleeve of her jacket. Wendy Baron has suggested that the ‘spiky white collar’ of Girl with Palmettes was a common trimming during the period since a similar one appears in a painting by Harold Gilman, The Coral Necklace 1914 (Brighton Museum and Art Gallery).10 Either the girl in the painting is wearing a different coat from the girl in the sketch or it is possible that Drummond changed small details of the woman’s costume from his initial observations, such as the colour of the coat and the appearance of the collar, to suit the overall aesthetic intentions of the oil painting.

An additional detail evident in Drummond’s pencil sketch which is not visible in the painting is the decorative ruffle or flower adorning the back of the model’s broad-brimmed hat. Up until the middle of the twentieth century, the hat was an essential feature of women’s dress, not only as a signifier of fashionable taste and the crowning accessory of any outfit but also as a necessary covering to the head and hair, representing respectability and propriety.11 In the early decades of the twentieth century, women of all social classes would have always worn a hat out of doors, and even frequently indoors when not within their own private domestic spaces.12 Whilst ladies of wealth would have owned a variety of elaborate and expensive creations for different occasions, reflecting changing fashions and tastes, women of limited financial means would have reused their hats, experimenting with trimmings and decorations to make the best of what they had. A diverse range of hat styles were common in Edwardian Britain prior to the First World War, from flat, small brimmed ‘boaters’ worn near the front of the head with the hair piled up underneath, to very large hats with wide brims accommodating lavish decorations of feathers, ribbons and flowers. Being relatively plain and unfussy, the purple hat worn in Girl with Palmettes is not a typically fashionable or dressy style. Wendy Baron has suggested that this type of hat was a style ‘worn by unfashionable women who moved in “arty” circles before the war’,13 but it is also reminiscent of the respectable but unremarkable clothing adopted by certain groups who prioritised practicality over ornamentation in dress, for example, working women, those engaged in charity or social work, or demonstrators for women’s suffrage. A similar hat is worn by the model in Gilman’s Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15 (fig.5).

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15

Oil on canvas

460 x 610 mm

Private collection

Fig.5

Harold Gilman

Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15

Private collection

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Flowered Hat or Someone Who Waits c.1907

Oil on canvas

508 x 406 mm

Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Fig.6

Spencer Gore

The Flowered Hat or Someone Who Waits c.1907

Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery

Drummond’s painting should be viewed in context with the subject matter of Gilman’s Girl with a Teacup and other paintings by his contemporaries such as Someone Who Waits 1907 by Spencer Gore (fig.6). These pictures feature young women in contemporary dress wearing hats, posed within a decorated interior. London women became a favourite subject for the Camden Town Group, particularly women from the urban working or lower middle classes. Although the sitters were often known personally to the artists, for example Walter Sickert’s paintings of his charlady Mrs Barrett, or Gilman’s Portrait of Mrs Victor Sly (Wakefield Art Gallery),14 a Fitzroy Street neighbour and friend of Ginner’s, they are not primarily portraits of individual characters. Rather they are representations of a collective urban breed, archetypes of a particular social existence and experience distilled within the visual detail of costume and environment.15 Although the direct and unaffected gaze of the sitter in Girl with Palmettes indicates that she appears to be quite comfortable in her role as model, the rigidity of her pose and the fact that she is wearing her hat indoors suggests that she is not fully at ease in her surroundings. Despite the striking impact of her presence, there is a lack of affection or complicity in the artist’s presentation of her. A balance is struck between intimacy and distance, and the model is vividly described but not emotionally characterised.

Nicola Moorby

April 2008

Notes

Information supplied to the author by Fiona McIntyre, email correspondence, 26 April 2008, Tate Catalogue file.

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (198).

Reproduced in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008 (48).

Related biographies

Related essays

- London’s Fashion Culture and the Camden Town Group Painters Christopher Breward

Related archive items

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Girl with Palmettes; ?Portrait of the Artist’s Wife c.1914 by Malcolm Drummond’, catalogue entry, April 2008, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www