Lucien Pissarro Almond Trees, Le Lavandou 1923

Lucien Pissarro,

Almond Trees, Le Lavandou

1923

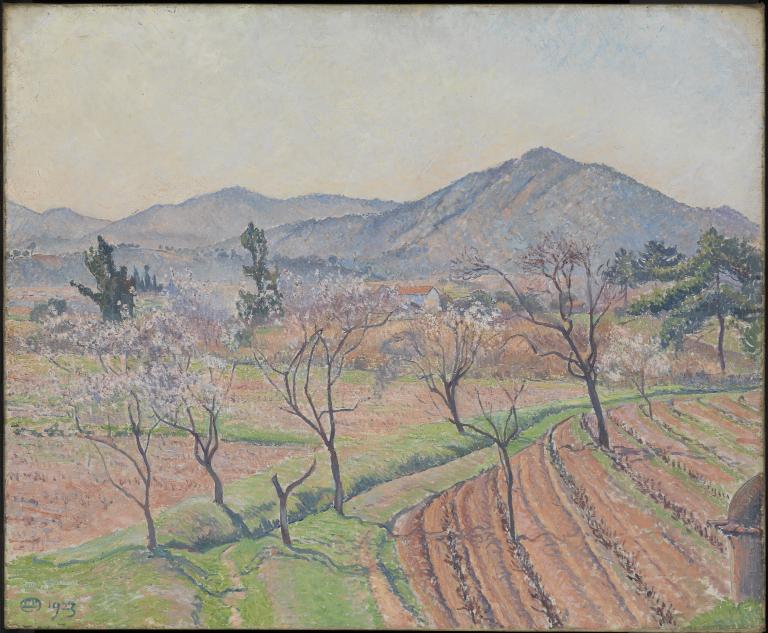

The setting of this painting is the small fishing village of Le Lavandou on the French Riviera where Pissarro stayed with his wife and aging mother during the winter and spring of 1922–3. His view depicts the local agriculture and the slowly emerging spring against a background of blue hills, avoiding more picturesque studies of the nearby ports. The pinks, whites and pale blues of the almond tree blossoms are the painting’s final touches; Pissarro began the picture before they were fully in bloom.

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944

Almond Trees, Le Lavandou

Les Amandiers, Le Lavandou

1923

Oil paint on canvas

597 x 730 mm

Inscribed ‘LP’ in monogram and ‘1923’ bottom left, and ‘Lucien Pissarro | The Brook, Stamford Brook Road, W.6. | 1 Les Amandiers, Le Lavandou | £130’ on handwritten label on stretcher cross member

Purchased 1924

N03865

Les Amandiers, Le Lavandou

1923

Oil paint on canvas

597 x 730 mm

Inscribed ‘LP’ in monogram and ‘1923’ bottom left, and ‘Lucien Pissarro | The Brook, Stamford Brook Road, W.6. | 1 Les Amandiers, Le Lavandou | £130’ on handwritten label on stretcher cross member

Purchased 1924

N03865

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist 1924.

Exhibition history

1923–4

Sixty-Ninth Exhibition of the New English Art Club, R.W.S. Galleries, London, December 1923–January 1924 (62).

1934

108th Exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, April–September 1934 (354, as ‘Les Amandiers: Le Lavandou’).

1935–6

Paintings and Drawings by Lucien Pissarro, (Art Exhibitions Bureau tour), City of Manchester Art Gallery, June–July 1935 (20), Williamson Art Gallery, Birkenhead, July–August 1935 (19), County Borough of Burton upon Trent Museum and Art Gallery, February 1936 (19), City of Belfast Museum and Art Gallery, May–June 1936 (36), Corporation Art Gallery, Rochdale, June–July 1936 (36), Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead, August 1936 (36, as ‘Almond Trees at Le Lavandou’).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January–February 1946 (69), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946 (69), Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946 (69, reproduced), Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946 (69), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Berne, August 1946 (71), Akademie der Bildenden Kunste, Vienna, September 1946 (72), Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946 (72), Muzeum Narodwe, Warsaw, November–December 1946 (72), Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (72), Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (3865).

1963

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944: A Centenary Exhibition of Paintings, Watercolours, Drawings and Graphic Work, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council Gallery, London, January–February 1963, Manchester City Art Gallery, March 1963, Bristol City Art Gallery, April 1963, Dundee City Art Gallery, May 1963, The Minories, Colchester, June 1963, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, July 1963 (47).

1970–5

Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, County Durham, September 1970–May 1975 (long loan).

2011

Pure Gold: 50 Years of the Federation of British Artists, Mall Galleries, London, February 2011 (not in catalogue).

References:

1926

J.B. Manson, Hours in the Tate Gallery, London 1926, pp.127–8, reproduced opposite p.128.

1929

J.B. Manson, The Tate Gallery, London 1929, pp.139–40, reproduced p.139.

1962

W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro: Un Coeur simple, London 1962, pp. 181–2.

1983

Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro, London 1983, no.360, reproduced p.167.

1983

John Bensusan-Butt, ‘Introduction’, in Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro, London 1983, pp.xv–xvi.

Technique and condition

Almond Trees, Le Lavandou is painted on a plain-weave linen canvas which has a white commercial ground. It is on a five-member softwood stretcher with iron tacks; it is not known if they are original.

The painting has been drawn in thin blue paint and then painted more or less alla prima in lean paint with moderately impasted brushstrokes. Triangular areas at the top left and right were left unpainted. The final impastos were dabbed on, which has left sharp peaked mounds of paint. In the sky Pissarro’s brushmarks form clear diagonal cross-hatched lines but are more irregular elsewhere following the drawing. The almond blossom appears to have been painted after the rest of the composition was completed and is less successfully integrated into the composition.

Compared to Pissarro’s much earlier April, Epping 1894 (Tate N04747), Almond Trees, Le Lavandou has thinner paint, more sparingly applied with significant gaps between applications where the ground shows through. Blue underpaint remains visible and the overall surface is more matt, possibly because the thinner paint has ‘sunk’ over the lean ground. The handling is also more confident and restrained; it retains its drawn quality, is more linear, and with less broken colour.

No varnish has been applied to the painting, but some accumulated surface dirt gives it a dusty appearance. There is evidence of handling and stacking in the studio, which has caused superficial damage to the still wet paint.

Stephen Hackney

July 2003

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', July 2003, in David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Almond Trees, Le Lavandou 1923 by Lucien Pissarro’, catalogue entry, October 2002, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

The clear winter sky of Provence is recorded in the light tonality of this painting. Le Lavandou, at the time this painting was made in 1923, was a small fishing village on the western end of the French Riviera, between Hyères and St Tropez. Pissarro’s diary for that year opens with him and his wife Esther staying at the Villa Boniol at Bormes-les-Mimosa, just outside Le Lavandou.1 They rented this house partly for reasons of his health, allowing him to escape the British winter, but also in order to be with his elderly mother, who was staying with them and was unwell (she died in 1926). They were able to afford this visit after the success of his exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London in October 1922.2 On 20 January, he started a picture of mimosas,3 and four days later began to paint the almond trees, as his diary reads:

January

24 Morning. drew in preparation for Almond Blossom.

25 Mrng. Continuation of preparation for Almond Blossom

26 dito

27 dito

28 Morning. Almond Blossom

29 Morning. Almond Blossom the flowers are very slow to come.

February

2 Mrg: did Almond Blossom

6 Morning worked at Almond Blossom the flowers are only beginning and give me a lot of trouble to put right with the rest of the picture.

7 mrng. Almond Blossom

13 Matin. Amandiers en Fleurs

14 Matin. Grey. Went to the Amandiers but sun disappeared. Could not work

15 Matin. finished Amandiers en fleurs.

24 Morning. drew in preparation for Almond Blossom.

25 Mrng. Continuation of preparation for Almond Blossom

26 dito

27 dito

28 Morning. Almond Blossom

29 Morning. Almond Blossom the flowers are very slow to come.

February

2 Mrg: did Almond Blossom

6 Morning worked at Almond Blossom the flowers are only beginning and give me a lot of trouble to put right with the rest of the picture.

7 mrng. Almond Blossom

13 Matin. Amandiers en Fleurs

14 Matin. Grey. Went to the Amandiers but sun disappeared. Could not work

15 Matin. finished Amandiers en fleurs.

It thus took twelve mornings’ work to make this painting over a period of twenty-three days, in the middle of which he seems to have slowed up to await the opening of the blossom. The colour is applied quite thinly in comparison to the earlier paintings by Pissarro in the Tate collection, and the white ground of the canvas shows through in various places, especially around the trunks and branches of the trees. The canvas is unpainted in each top corner, behind the rebate of the frame, perhaps because of some clips to keep it on the easel. The blossom of the five almond trees is dabbed on top of the painting of the branches, in shades of pink with blue, red and mauve.

The mountains at Le Lavandou go right down to the sea, and in choosing subjects to paint Pissarro avoided the port and the more picturesque views of the slopes. The practice of local farming is illustrated clearly in this painting, and the shadows of the trees make switchbacks which emphasise the furrows, and he includes at the lower right corner a farmer’s hut of stone. This orchard and level field is the kind of subject that had appealed to Vincent van Gogh in Provence, or, in northern France, to his father Camille Pissarro. The family conversation at this time was at least once about Camille’s painting: just after Lucien had completed The Almond Trees, he recorded in his diary on 18 February: ‘No work. Scene parce que maman pretend que [Scene because mama claims that] father did work only to make money.’ Thus, even in the 1920s, Lucien was still not far from the world of the first impressionists.

Camille Pissarro 1830–1903

A Corner of the Meadow at Eragny 1902

Oil on canvas

support: 600 x 813 mm; frame: 857 x 1056 x 95 mm

Tate N06003

Presented by Mrs Esther Pissarro, the artist's daughter-in-law 1951

Fig.1

Camille Pissarro

A Corner of the Meadow at Eragny 1902

Tate N06003

The curator and conservative critic James Laver wrote at the time that the Provençal paintings were Pissarro’s best:

England has not always been able to give him the sunlight which his method expresses best ... although Pissarro has painted many English subjects ... he returns with evident pleasure ... particularly to Le Lavandou, the little town in Var, on that delightful part of the Mediterranean coast with lies opposite the Iles d’Hyères. Here he has painted the hills in sunshine, the purple shadows of tall trees, the sea dancing with light, the delicacy of Mimosas, the subtle contrasts of Reeds and Peaches. The wheel has come full circle, the young Impressionist, and the cultured decorator of books ... have met in a single individual ... working at an art which is the full expression of a serene and harmonious personality.6

Pissarro’s paintings of Provence sold well in an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, London, in October 1924. The row with his mother on 18 February the year before may have been because Lucien felt defensive about painting subjects as popular as the south of France. Pissarro’s friend J.B. Manson reproduced the painting in both his books on the Tate Gallery, in 1926 and 1929, praising it for its accuracy of colours, the ‘extraordinary effect of recession with pure colour’.7

Anne Thorold mentions that a drawing of this composition belonged in 1958 to Raymond Mortimer (1895–1980).8 Mortimer, a literary critic and one of the Bloomsbury circle, wrote the ‘Appreciation’ in the catalogue of Pissarro’s memorial exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in January 1946.9 He praised Pissarro for his professionalism and seriousness, describing him as a nineteenth-century French artist, in a separate category from a slightly younger but more modern artist like Henri Matisse.

David Fraser Jenkins

October 2002

Notes

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

David Fraser Jenkins, ‘Almond Trees, Le Lavandou 1923 by Lucien Pissarro’, catalogue entry, October 2002, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www