Lucien Pissarro April, Epping 1894

Lucien Pissarro,

April, Epping

1894

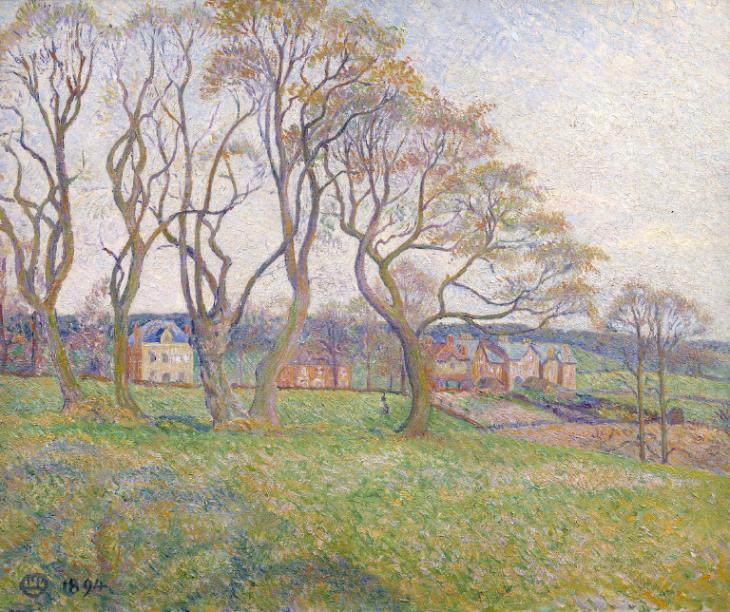

Lucien Pissarro almost always painted his landscapes in front of the subject. He completed this picture shortly after settling in Britain, in Epping in Essex. The canvas is covered in thick layers of paint, dominated by the expanse of grass in the foreground with dabs of differing colours creating a sense of recession to the houses beyond. A line of trees in the middle ground dwarf a woman in a black cloak crossing the field. The oranges, mauves and blues in the lower left corner form a shadow cast by a tall tree in this daytime spring scene.

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944

April, Epping

1894

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 730 mm

Inscribed ‘LP’ in monogram and ‘1894’ bottom left, and ‘L. Pissarro | The Brook | Hammersmith’ and on cross member ‘April | Epping (Essex) | 1894’ on back at left

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1934

N04747

1894

Oil paint on canvas

603 x 730 mm

Inscribed ‘LP’ in monogram and ‘1894’ bottom left, and ‘L. Pissarro | The Brook | Hammersmith’ and on cross member ‘April | Epping (Essex) | 1894’ on back at left

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1934

N04747

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1934, by whom presented to Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1904

Thirty-Third Exhibition of Modern Pictures held by the New English Art Club, Dudley Gallery, London, November–December 1904 (68, as ‘April – Epping’).

1907

Contemporary British Painting and Sculpture, Spring Exhibition, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, February–April 1907 (118, as ‘April –Epping’).

1913

The Sixth London Salon of the Allied Artists’ Association, Royal Albert Hall, London, July 1913 (865, £60).

1920

Retrospective Exhibition: Paintings and Drawings by Lucien Pissarro, Hampstead Art Gallery, London, October–November 1920 (7, 90 guineas).

1930

The Camden Town Group: A Review, Leicester Galleries, London, January–February 1930 (27, as ‘Epping’).

1934

Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy, London, May–August 1934 (94).

1949

The Chantrey Collection, Royal Academy, London, January–March 1949 (201).

1958

A Selection from the Chantrey Bequest, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, April 1958 (59).

1963

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944, A Centenary Exhibition of Paintings, Watercolours, Drawings and Graphic Work, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council Gallery, London, January–February 1963, Manchester City Art Gallery, March 1963, Bristol City Art Gallery, April 1963, Dundee City Art Gallery, May 1963, The Minories, Colchester, June 1963, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, July 1963 (14).

1965–76

Castle Museum, Norwich, May 1965–December 1976 (long loan).

References

1949

‘A Selection from a Notable Exhibition: the Entire Chantrey Collection at the Royal Academy’, Illustrated London News, 8 January 1949, p.55.

1962

W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro: Un Coeur simple, London 1962, pp.7, 206.

1965

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1965, p.527.

1983

Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro, London 1983, no.85, reproduced p.71.

1992

Nicholas Reed, Pissarro in Essex, London 1992, p.12, reproduced p.13.

1999

Frances Stenlake, From Cuckfield to Camden Town: The Story of Artist Robert Bevan, Cuckfield 1999, p.55.

Technique and condition

April, Epping has been painted on a plain linen canvas with a white (presumably lead) commercial ground on a five-member softwood stretcher, which has its tacks in the original position. Stencilled on the reverse of the canvas is the artists’ colourman stamp ‘P. Contet | Paris | 54 Rue LaFayette 54’.

There is no evidence of drawing, but this would not be visible through the paint film as the paint covers nearly all of the ground. The trees have a linear appearance suggesting that they were drawn with a brush in lean paint. Overall, April, Epping has been quite thickly painted using a dabbing technique with a flat square-ended bristle brush, heavily loaded. Paint has dried in small raised areas and is flicked into pointed impasto in many places. Pissarro’s brushwork provides a deliberately strong diagonal movement in the open area of the sky and more varied direction elsewhere where the brush has followed the design, such as around the trees.

The colours would have been mixed on a palette, using white in most mixtures to give opaque and bright colours. These have been applied wet-in-wet in campaigns for each colour across the composition, juxtaposing dabs of different, sometimes contrasting, colours. Some of the darker coloured shadows around the trees are less opaque. There is no varnish and the paint is relatively glossy.

Stephen Hackney

July 2003

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', July 2003, in David Fraser Jenkins, ‘April, Epping 1894 by Lucien Pissarro’, catalogue entry, October 2002, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

The earliest of Lucien Pissarro’s paintings in the Tate collection, made a few years after he settled in Britain, April, Epping 1894 reflects the artist’s continuing admiration for Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, the ‘neo-impressionist’ or ‘divisionist’ artists with whom he had been friends in Paris. For a few years his father Camille had also been an enthusiastic practitioner of divisionism, the style of painting in dots of light colour favoured by Seurat and Signac, and all four artists had shown as a group in Paris in 1886, in the last of the series of impressionist exhibitions. Lucien was then still living with his father, and had introduced him to these younger painters. Camille did not persist with this laborious way of applying oil paint, but during the 1890s his pictures of, for example, the port of Rouen, are still speckled with luminous touches of colour. Similarly, in his first paintings in Britain, Lucien did not continue to apply separate dots, as he had done in landscapes he painted in France until 1890. He wrote to his father on 11 March 1894: ‘je ne me suis en aucune façon préoccupé de la division’ (I am not in the slightest concerned with divisionism).1

In this view of Epping, Pissarro stood with his back to the sun facing a field, a row of trees, and some houses along a road in the clear sunlight of a spring day. He covers the expanse of the foreground with ordered, criss-crossed touches of paint, mostly light green but with a variety of other colours, showing recession by means of colour.2 In the left corner the shadow of a large tree falls across the field; it is painted with orange, mauve and blue touches among the green of the meadow, so allowing Pissarro to demonstrate a key principle of impressionism: that shadows are coloured. At the centre of the composition a woman dressed in a black cloak walks just behind the line of trees. Four of the houses at the right have long kitchen gardens. The painting is a recreation of a sunlit landscape, but it also emphasises the village economy of the tended gardens.

Pissarro almost always painted his landscapes directly, on the spot, out of doors, and hence chose places within walking distance of where he was staying. He and his wife Esther moved to Epping in Essex in July 1893, renting a small house at 44 Hemnall Street.3 He wrote to his father that he had noticed lots of suitable landscapes for painting nearby, just as at the family home in Eragny in northern France, except on a larger scale, with pretty cottages and the wild forest. He added for his mother that he and Esther were able to have a much larger house at Epping, with a little garden in front and a ‘gentil petit bout de jardin à l’anglais dont je suis tout à fait amoureux’ (sweet patch of English garden that I love dearly).4 The site of this particular painting has not been identified with certainty. It is not anywhere immediately near the Pissarros’ house, and judging from the character of the buildings and the size of the trees may be in the Copped Hall Estate, about a mile to the south of Epping.5 If this is so, he would have had to have gone some distance to find this view.

Pissarro was still using materials from France, and the canvas is French size 20, the largest size he used regularly, supplied by P. Contet at 54 rue Lafayette in Paris. The white ground of the canvas is almost entirely covered, but in some areas it can be seen that he first sketched the outlines with dark blue paint. Immediately after he painted this picture Pissarro again wanted to change his technique, and in May 1894 he wrote to his father asking for new materials and ‘des pinceaux courts, comme ceux dont se servait Cézanne ... car je vais tacher de peindre tout autrement’ (short brushes, like the ones Cézanne used ... because I am going to try to paint in an entirely different way).6

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944

The Garden Gate, Epping 1894

Oil paint on canvas

540 x 650 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Lucien Pissarro

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.1

Lucien Pissarro

The Garden Gate, Epping 1894

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Lucien Pissarro

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The paintings Pissarro first made in Britain were not publicly exhibited for a long time. He was known in London for his prints and illustrated books, and his emergence as a painter was delayed for years after he suffered a stroke in 1897. He made no paintings during the following five years, and then rather few. Only in 1904, coincidentally the year after his father’s death, were his paintings seen in public, when he exhibited at the New English Art Club as a ‘non-member’ with this painting and The Garden Gate. From 1906 he regularly showed his new paintings at the New English Art Club. The compiler of Pissarro’s catalogue raisonné, Anne Thorold, suggests that this painting was also exhibited there in November 1906 as Epping, Early Spring, but the absence of a mention in reviews, and the fact that the picture had already been shown there in 1904, make this uncertain.9 At the Whitechapel Art Gallery in February 1907 he showed this painting, again with The Garden Gate, in the ‘New English Art Club’ section of ‘Contemporary British Painting and Sculpture’. He showed work in all three Camden Town Group exhibitions, sending some earlier paintings as well as new ones, but his first solo exhibition of paintings was at the Carfax Gallery in May 1913. His first British paintings can be seen as a decline, and his painting was not really reborn after he left France and after his work was interrupted by his illness, until about 1906. This makes Pissarro difficult to place in terms of his generation, but comparable to his contemporary Walter Sickert, who also re-emerged in London in 1905 on his return from France.

The Tate Gallery Trustees accepted at the same meeting in January 1934 the gifts of this painting and All Saints’ Church, Hastings (Tate N04748), both of which had been already purchased for the Chantrey Collection by the Royal Academy on 10 January. Both pictures had previously been listed as for sale in Pissarro’s retrospective exhibition at the Hampstead Art Gallery in October 1920 (April, Epping for 90 guineas), but the occasion for the Chantrey purchase (April, Epping for 150 guineas) may have been the preparation of the large touring exhibition of Pissarro’s work that began at Manchester in 1935. The Tate Trustees had already considered buying one of Pissarro’s Epping paintings in January 1930, but deferred their decision until their next meeting, when the picture was to be seen, although nothing in fact happened until 1934.

The painting was requested for The Camden Town Group exhibition at Southampton Art Gallery in 1951, and although the Trustees agreed to lend (along with paintings by J.B. Manson and J.D. Innes) it was not included. Of the seven landscapes by Pissarro listed in the exhibition catalogue, six are marked with an asterisk as for sale from either the Leicester Galleries or Esther Pissarro, and it may be that the inclusion of these led to a revision of the lending request to the Tate.

David Fraser Jenkins

October 2002

Notes

Lucien Pissarro, letter to Camille Pissarro, 11 March 1894, in Anne Thorold (ed.), The Letters of Lucien to Camille Pissarro, 1883–1903, Cambridge 1993, p.359.

Other examples of this use of an empty expanse of vibrant green are Marais de Bazincourt 1887 and La Prairie de Tierceville, temps gris 1888, both reproduced in Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionnisme anglais, exhibition catalogue, Musée de Pontoise 1998, pp.18–19.

Related biographies

Related essays

- The Camden Town Group and Early Twentieth-Century Ruralism Ysanne Holt

- The Camden Town Group: Then and Now Ysanne Holt

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

David Fraser Jenkins, ‘April, Epping 1894 by Lucien Pissarro’, catalogue entry, October 2002, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www