Slade School Influences on the Camden Town Group 1896–1910

Emma Chambers

More than half the members of the Camden Town Group studied at the Slade School. Emma Chambers shows how the character and ethos of the Camden Town Group were influenced by the Slade curriculum and looks at the networks the art school created.

The Slade School of Fine Art’s influence on the development of the Camden Town Group is evident not only in the impact of its training on individual artists, but also in the way that it created the conditions in the London art world in which Camden Town Group subject matter and alliances became possible. Over half of the Camden Town Group members trained at the Slade. Walter Sickert spent a term there in 1881 before leaving to study with Whistler; Harold Gilman, Spencer Gore, Augustus John and Wyndham Lewis studied at the Slade in the 1890s; while Malcolm Drummond, James Dickson Innes and Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot trained there in the 1900s.1

Students entering the Slade began by drawing from the Antique in the cast room until judged competent to progress to the life room. Life drawing was the most important component of the Slade curriculum. Models sat in the life room every day and the students spent the majority of their time drawing from life and draped models, progressing to painting from the model when judged sufficiently advanced. Composition subjects were set by the Slade Professor once a month and there were lectures on anatomy and perspective.2 Outside the formal classes, students were also encouraged to study the Old Masters at the National Gallery and British Museum and to contribute to the monthly ‘Sketch Club’ for which composition titles were set.3 Each year, prizes were awarded for figure composition painting (the Summer Composition Competition), figure painting, head painting, figure drawing, antique drawing, sculpture and fine-art anatomy.4 John, Lightfoot and Innes were the most successful of the future Camden Town Group artists in winning prizes and scholarships at the school; those artists, in fact, that are least typical of the group.5 More modest successes were enjoyed by Lewis and Gilman, but Gore won no prizes or scholarships.6

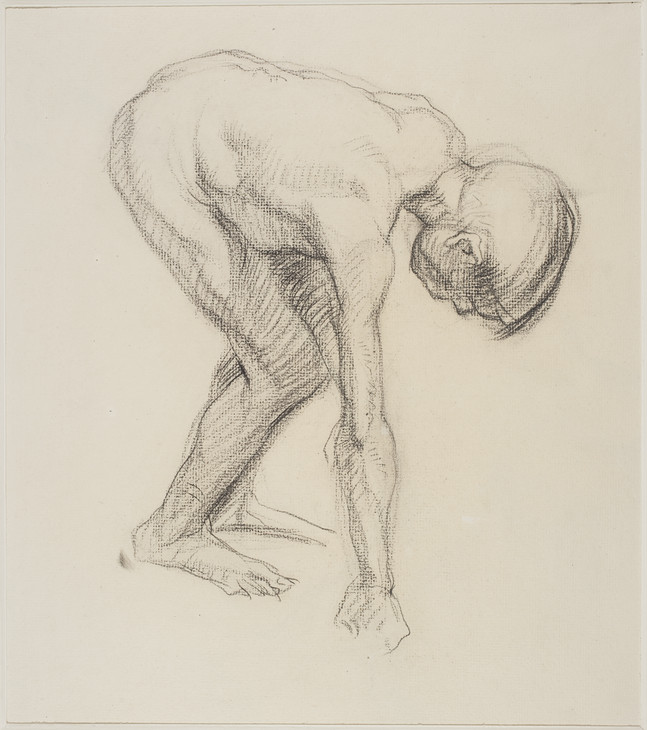

Wyndham Lewis 1882–1957

Stooping Nude Boy 1900

Black chalk on paper

391 x 353 mm

UCL Art Collections. Slade: Scholarship 1900.

© By kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity)

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Fig.1

Wyndham Lewis

Stooping Nude Boy 1900

UCL Art Collections. Slade: Scholarship 1900.

© By kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity)

Photo © UCL Art Collections

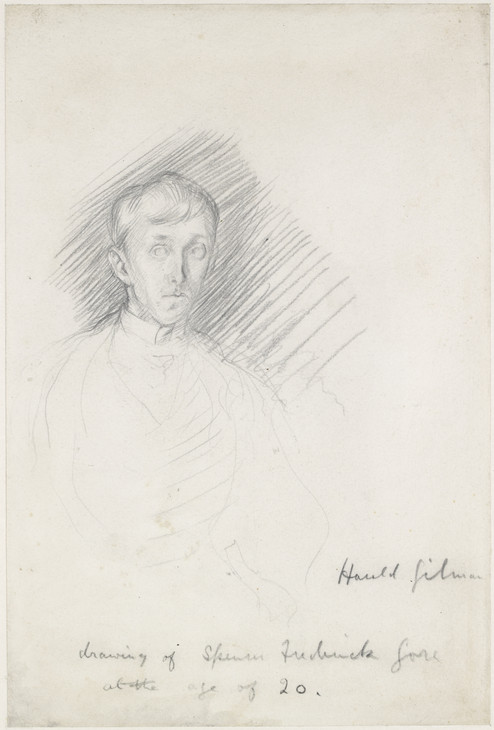

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Portrait of Spencer Frederick Gore 1898–9

Pencil on paper

275 x 183 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

Portrait of Spencer Frederick Gore 1898–9

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum

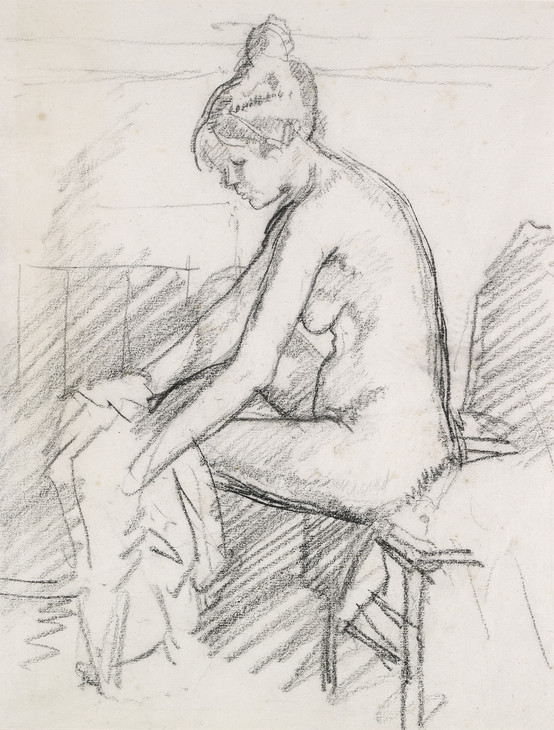

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Study of a Nude Female, Seated, Drying her Right Foot Not dated

Charcoal on paper

349 x 263 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum

Fig.3

Harold Gilman

Study of a Nude Female, Seated, Drying her Right Foot Not dated

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum

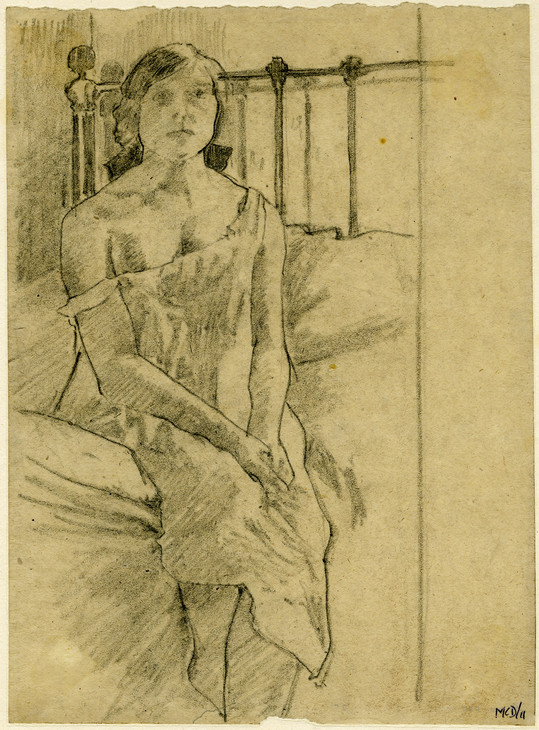

Malcolm Drummond 1880–1945

A Woman Seated on a Bed, Her Hands Crossed Not dated

Pencil on paper

243 x 180 mm

British Museum, London

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.4

Malcolm Drummond

A Woman Seated on a Bed, Her Hands Crossed Not dated

British Museum, London

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

While the emphasis in the Slade curriculum on life drawing and figure composition in the tradition of the Old Masters might seem to be a world away from the figure studies in modest domestic interiors and the urban landscapes that formed the primary subject matter for the Camden Town Group, the intensive training in objective observation in the life room that formed the core of the curriculum translated easily into the ‘objective perceptual honesty’ that has been identified as a unifying principle among the diverse artists that composed the Camden Town Group.7 Drawing tutor Henry Tonks emphasised the importance of close observation of the model, and drawing was seen primarily as a tool for exploring form. Slade student drawing in the 1890s and 1900s was usually in pencil or black chalk and characterised by strong outline, with a special attention to contours affected by the bone structure and musculature of the model, and schematic diagonal shading, as can be seen in this characteristic Slade drawing by Lewis (fig.1). This is one of the very few surviving drawings by members of the Camden Town Group when they were students at the Slade. The only known student-period work by Gilman is a portrait of Spencer Gore (fig.2); but a comparison of Gilman’s later studies (fig.3) with Lewis’s work shows how a Slade method of drawing the figure still influenced his work even as he extended it to encompass the classic Camden Town subject matter of a nude in a bedroom interior. Malcolm Drummond’s drawings (fig.4), on the other hand, show little evidence of Slade draughtsmanship and are much more influenced by Sickert, with whom he studied at the Westminster School of Art after leaving the Slade. However, while the Slade tradition of drawing emphasised the figure in isolation, Sickert was much more concerned with the relationship of figures and objects to their settings.8 Despite these differences of drawing style, both Sickert and the Slade shared a belief in the importance of observation from nature and its objective transcription in drawing and painting as a means of capturing experience.9

Links between Slade subject matter and Camden Town painting

The subject matter of Slade student paintings consisted primarily of small-scale nudes and half-length portraits and provided a useful grounding for the figure studies in domestic interiors that were to become the primary subject matter of Camden Town Group artists. Lightfoot’s prize-winning life painting of 1909 (fig.5) demonstrates the skill that Slade students developed in rendering the subtle shifts of flesh-tones, the fall of light on the model and the juxtaposition of the figure with the drapery and furniture of the life room, skills that translated easily into painting Camden Town female nudes in interiors, albeit with different handling of paint. Slade painting tutor Philip Wilson Steer had pioneered intimate interior nudes in the 1890s, inspired by the French impressionists, and his students began to paint in this genre once they left the school.10 The head-painting prize also developed skills in small-scale portrait painting, and prize-winning works in this category in the 1900s, such as Philip Dadd’s Portrait of a Woman Wearing a Green Jersey 1903 (fig.6), prefigure the simplicity and directness of Camden Town portraiture.

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot 1886–1911

Male Figure Standing 1909

Oil paint on canvas

915 x 610 mm

UCL Art Collections. Slade: First prize figure painting, 1909.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Fig.5

Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot

Male Figure Standing 1909

UCL Art Collections. Slade: First prize figure painting, 1909.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Philip Dadd 1880–1916

Portrait of a Woman Wearing a Green Jersey 1903

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 457 mm

UCL Art Collections. Slade: First prize head painting, 1903.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Fig.6

Philip Dadd

Portrait of a Woman Wearing a Green Jersey 1903

UCL Art Collections. Slade: First prize head painting, 1903.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

For the Slade’s Summer Composition Competition, students were given a set title taken either from literary sources such as the Bible or the classics, or themes such as ‘bathers’ or ‘labourers’, and required to compose large-scale paintings which placed groups of figures in a setting. Allied to the tradition of History painting, central to academic art training from the seventeenth century, this competition gave the students considerable scope for exploring different models of narrative painting. While some prize-winning paintings, such as Augustus John’s Moses and the Brazen Serpent 1898 (UCL Art Collections), were grandiose confections of Old Master contrapposto figures, albeit combined with an incongruous impressionist handling of paint derived from Steer, the prize also offered the opportunity to produce more modest narrative paintings of proto-Camden Town subject matter. Albert Rutherston’s The Confessions of Claude 1901 (fig.7), based on a novel by Émile Zola, sets the scene where the hero confronts his lover about her betrayal in a bare domestic interior dominated by an iron bedstead, anticipating the narrative domestic dramas and the sexual tensions played out in Sickert’s paintings of male and female figures in dingy interiors.11

Albert Rutherston 1881–1953

The Confessions of Claude 1901

Oil paint on canvas

749 x 978 mm

UCL Art Collections. Slade: First prize Summer Composition Competition, 1901.

Courtesy of the artist’s grandchildren

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Fig.7

Albert Rutherston

The Confessions of Claude 1901

UCL Art Collections. Slade: First prize Summer Composition Competition, 1901.

Courtesy of the artist’s grandchildren

Photo © UCL Art Collections

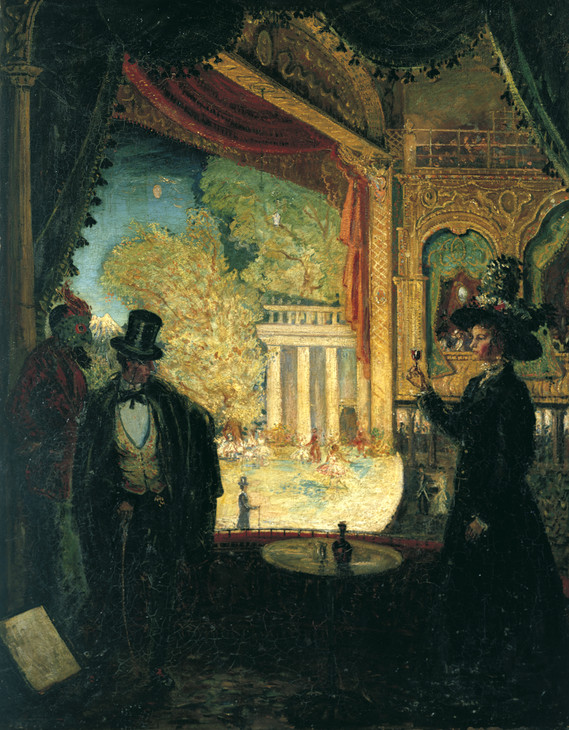

James Dickson Innes 1887–1914

A Scene in a Theatre 1908

Oil paint on canvas

1372 x 1067 mm

UCL Art Collections. Slade: ?First prize Summer Composition Competition, 1908.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Fig.8

James Dickson Innes

A Scene in a Theatre 1908

UCL Art Collections. Slade: ?First prize Summer Composition Competition, 1908.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Rule Britannia 1910

Oil paint on canvas

unconfirmed: 762 x 635 mm; frame: 970 x 845 x 115 mm

Tate T06521

Presented by the Patrons of British Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1992

Fig.9

Spencer Gore

Rule Britannia 1910

Tate T06521

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Fig.10

Walter Richard Sickert

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Innes’s intriguing and mysterious Scene in a Theatre 1908 (fig.8) has stylistic links with both Sickert’s and Gore’s theatre scenes and was painted in a year when Innes was in close contact with both artists. The side view onto the brightly lit stage from the darkened box in the foreground is similar to the compositional structure of some of Gore’s Alhambra paintings (fig.9), and Innes also quotes from Sickert’s Noctes Ambrosianae 1906 (fig.10), exhibited at the New English Art Club (NEAC) in 1906, in the depiction of the audience in the gallery in the upper right of the painting. Theatre scenes by Camden Town artists have been compared with Sickert’s paintings of the late 1880s, themselves derived from Edgar Degas’s compositional formula of a floodlit stage seen behind the silhouetted heads of figures in the orchestra and audience.12 However, Innes’s painting emerges from a tradition of theatre painting that is as much influenced by William Orpen’s Play Scene from ‘Hamlet’ (private collection),13 winner of the Summer Composition Competition at the Slade in 1899, and on display in the school when both Gore and Innes were students.14

While Sickert’s theatre scenes of this period have a clear separation between stage and audience and evoke a world of earthy working class entertainment, both Orpen’s and Innes’s works create an aura of mystery where the relationship between performers and spectators is ambiguous, and mysterious masked figures appear as part of the audience. This atmosphere of mystery is also visible in Gore’s early theatre scenes such as The Masked Ball 1903,15 and The Mad Pierrot Ballet, The Alhambra c.1905 (private collection),16 where the antics on stage have a sinister quality. Gore’s son noted his father’s fascination with Francisco Goya’s carnival scenes, and described how his early drawings evoked ‘a strange dark world of characters from Lenten Carnival and Commedia dell’Arte; clowns, circus animals and sylphides riot and posture across an undefined stage’.17

Sir William Rothenstein 1872–1945

Mother and Child 1903

Oil on canvas

support: 969 x 765 mm; frame: 1270 x 1025 x 90 mm

Tate T05075

Purchased 1988

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.11

Sir William Rothenstein

Mother and Child 1903

Tate T05075

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Sir William Orpen 1878–1931

The Mirror 1900

Oil on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 682 x 580 x 75 mm

Tate N02940

Presented by Mrs Coutts Michie through the Art Fund in memory of the George McCulloch Collection 1913

Fig.12

Sir William Orpen

The Mirror 1900

Tate N02940

In addition to the Slade’s contribution to the development of Camden Town Group theatre scenes, former Slade students such as Orpen and William Rothenstein also pioneered the genre of the ‘portrait interior’ in the early 1900s, which laid the ground for the domestic interior subjects of the Camden Town Group. Drawing on a tradition of small-scale domestic studies by Whistler and his followers in the 1880s, works such as Rothenstein’s The Browning Readers 1900 (Bradford Art Galleries and Museums) and Mother and Child 1903 (Tate T05075, fig.11) and Orpen’s The Mirror 1900 (Tate N02940, fig.12) and The Chess Players 1902 (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) were conceptualised as portraits in which the relationship between the sitters and the class-specific contemporary domestic setting were an important part of the meaning of the picture.18 These early ‘portrait interiors’, where setting and figure are equally important, coupled with the influence of the ‘intimiste’ portraiture of Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard, with whom Sickert had had close links in France, and whose influence on Gilman and Gore was noted by contemporary critics,19 contributed to the character of Camden Town Group domestic subjects. Early interior portraits by Gilman, such as Edwardian Interior c.1907 (Tate T00096, fig.13), are more directly influenced by Rothenstein’s works, with their convivial and comfortable middle class interiors, than Sickert’s. However, Sickert’s influence is much more obvious in later works by Gilman such as Tea in the Bedsitter 1916 (Huddersfield Art Gallery),20 which tackles a more modest social class and conveys more ambiguous messages about relationships and the home, which echo paintings such as Sickert’s The New Home 1908 (Ivor Braka Ltd).21 Innes also tackled interior subjects in the period when he first became involved with the Fitzroy Street Group, including the portrait-interior Resting (private collection) and The Corner of a Room (fig.14), all painted around 1908.22

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Edwardian Interior c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

support: 533 x 540 mm

Tate T00096

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1956

Fig.13

Harold Gilman

Edwardian Interior c.1907

Tate T00096

James Dickson Innes 1887–1914

The Corner of a Room 1908

Oil paint on canvas

915 x 660 mm

UCL Art Collections. Slade student work.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Fig.14

James Dickson Innes

The Corner of a Room 1908

UCL Art Collections. Slade student work.

Photo © UCL Art Collections

Slade social networks and the London art world

The Slade’s contribution to the formation of the Camden Town Group was far greater than artistic training and subject matter, and should also be understood in terms of the wider influence of former Slade students in the London art world. The school was a site for the formation of life-long friendships and artistic collaborations, such as that between Gilman and Gore; introductions, as between Sickert and Gore, were effected through mutual Slade contacts such as Rutherston.23 Slade links also ensured support for the Camden Town Group by successful artists like John.

The London art world was dominated by informal groupings of artists which were important in providing opportunities to debate, exhibit and promote their work. In the 1890s the Slade faction was seen as a progressive grouping for younger artists allied to the NEAC to counter the traditional approach and established artists of the Royal Academy. Sickert had a long-standing friendship with Slade tutors Tonks, Steer and Frederick Brown. He had joined the NEAC in 1888, allying himself with these painters who then represented a grouping within the society inspired by the French impressionists.24 Brown was appointed Slade Professor in 1892 and appointed Tonks and Steer to the Slade staff. These three artists now wielded considerable influence on the jury of the NEAC, and with the proprietors of commercial galleries such as the Carfax Gallery used this influence to promote the careers of former Slade students.25 But by the mid-1900s other groupings had begun to form around Roger Fry and Vanessa and Clive Bell and the Bloomsbury artists.

The Slade, NEAC and future Camden Town Group artists were primarily aligned with a ‘realist’ position emphasising the importance of observation from nature and concerned with the means by which art was produced, while the ‘formalist’ grouping of artists who were allied with Roger Fry proposed an art of ideas and were concerned with the effect of the artwork on the viewer.26 While these groupings were not watertight and artists often moved in both circles, most future Camden Town Group artists were primarily allied with the Slade faction and benefited from these contacts.27 Informal forums were important in consolidating alliances between like-minded artists and critics. One such forum was the weekly ‘At Homes’ organised by Sickert at his studio in Fitzroy Street, while Bloomsbury artists congregated at Vanessa Bell’s Friday Club.28

Sickert had been opening his studio at 8 Fitzroy Street every Saturday afternoon from 1905 with regular visitors Rothenstein, Walter Russell, Rutherston, Gore and Gilman. In 1907 this arrangement was formalised as the Fitzroy Street Group, a social and commercial partnership with a select group of like-minded artists which included these six painters together with Ethel Sands, Nan Hudson, Lucien Pissarro and George Thompson. They rented space at 19 Fitzroy Street in order to show their pictures to other artists, critics and potential patrons. Most of these artists had close links to the Slade and already exhibited at the NEAC,29 but the creation of the Fitzroy Street Group gave them the opportunity to show their pictures on a more regular basis and in a more informal setting than the exhibiting societies and commercial galleries could offer. Slade links ensured that collectors attended the gatherings, as did Slade tutors Tonks and Steer, and Slade artists John and Innes who both lived in Fitzroy Street.30

When Sickert began to teach at the Westminster School of Art in 1908 some of his pupils such as former Slade student Malcolm Drummond began to attend, and it was in this year that the Slade dominance of the Fitzroy Street Group began to fade, with Rothenstein, Rutherston and Russell rarely attending, and new members Walter Bayes, Robert Bevan and Charles Ginner taking their place. By 1910 the Fitzroy Street Group gatherings included a wide circle of artists loosely linked by personal and professional relationships rather than a common artistic ideology.

The art historian Wendy Baron credits Sickert with the creation of ‘an ambience in London wherein young painters could encourage each other towards independence and professional self-confidence’,31 and Sickert certainly played a major role in creating this environment. But also important was the compatibility of aesthetic ideology, working methods and subject matter and the pre-existing personal links that had been formed early on in the careers of many of the Camden Town Group artists through their training at the Slade. The Fitzroy Street Group demonstrates the importance of the networks facilitated by Slade contacts. It provided a meeting place for artists, critics, dealers and collectors where new ideas could be explored and exchanged and it was from this fertile ground that the Camden Town Group was born.

Notes

Their student dates are as follows: Sickert 1881, John 1894–8, Gore 1896–9, Gilman 1897–1901, Lewis 1898–1901, Drummond 1903–7, Innes 1906–8, Lightfoot 1907–9, Ratcliffe 1910.

Department of the Fine Arts: Slade School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, ‘Courses of Study’, College Calendar, University College London 1898–9. Lectures in History of Art taught by D.S. MacColl began in 1904; Department of the Fine Arts: Slade School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, ‘Courses of Study’, College Calendar, University College London 1904–5.

Albert Rutherston’s letters to his parents on starting at the Slade in 1898 provide an interesting account of the day-to-day student experience. He began by drawing in the antique studio, progressing to the life room after only three weeks having completed a satisfactory drawing. He recounts regular visits to the National Gallery to draw the Old Masters, drawing compositions for the Slade Sketch Club, visits to exhibitions and a boating trip with Gore and Orpen to work from nature. Tate Archive TAM 50.

Faculties of Arts and Laws and of Science, ‘Prizes and Certificates: Fine Art’, College Calendar, University College London 1898–9.

John was awarded a Slade Scholarship in 1896, won first prize for life drawing in 1897, and second prize for life painting and first prize in the Summer Composition Competition in 1898. Innes was awarded a Slade Scholarship in 1907 and won first prize in the Summer Composition Competition in 1908. In 1909 Lightfoot won first prizes in figure painting, head painting, painting from the cast and the Summer Composition Competition, and second prize in figure drawing. Faculties of Arts and Laws and of Science, ‘Prizes and Certificates: Fine Art’, College Calendar, University College London 1896–1910.

Lewis was awarded a Slade Scholarship and a certificate for figure drawing in 1900, and Gilman was awarded certificates for head painting and figure drawing in 1900. Faculties of Arts and Laws and of Science, ‘Prizes and Certificates: Fine Art’, College Calendar, University College London 1896–1901.

Gore’s letters reveal that he favoured Sickert’s approach to drawing over the Slade’s. He wrote: ‘I prefer such drawings as Sickert’s which always take place somewhere to John’s which take place nowhere’. Gore correspondence (no date or correspondent given), quoted in John Woodeson, ‘Introduction’, in Frederick Spencer Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, The Minories, Colchester 1970, unpaginated.

Sickert’s preface to the London Impressionists exhibition stressed the distinction between realism which recorded a subject ‘merely because it exists’ and artists who searched ‘through visible nature for ... beauty’ and made ‘a persistent effort to render the magic and the poetry which they daily see around them’. See Walter Sickert, ‘Preface’, in A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London, December 1889, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.60. In 1907 the Slade issued a publication that stressed the centrality of observation and truth to nature to contemporary artistic practice and saw a continuity in this practice from the Pre-Raphaelites through impressionism to contemporary artists allied to the New English Art Club. John Fothergill’s essay on the Slade’s concept of drawing stated the school’s opposition to artistic style that imitated the work of other artists rather than evolving out of direct observation: ‘Style then, is the expression of a clear understanding of the raw material from which the artist makes his creation. In drawing, the raw material is the forms of nature. Without this clear understanding no style is possible.’ John Fothergill, ‘The Principles of Teaching Drawing at the Slade School’, in The Slade: A Collection of Drawings and some Pictures done by Past and Present Students of the London Slade School of Art 1893–1907, Slade School, London 1907, p.35. Interestingly, some of the ideas expressed in this publication are similar to those expressed in Charles Ginner’s essay on Neo-Realism published in the New Age, 1 January 1914.

Both William Orpen’s The English Nude 1900 (Mildura Arts Centre) and Albert Rutherston’s Nude in Bed 1904 (present location unknown, reproduced in Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’, Burlington Magazine, vol.83, no.485, August 1943, pl.IIA, facing p.202), tackle the theme of a nude in a domestic interior that was to become a staple part of Camden Town subject matter, although Orpen’s inspiration is from an Old Master rather than contemporary source, Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at her Bath 1654 (Louvre, Paris). See Robert Upstone, William Orpen: Politics, Sex and Death, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2005, pp.24–7.

According to Wendy Baron, Sickert first began to draw nudes on metal bedsteads in Dieppe in 1902 and on his return to Dieppe from Venice in 1904 he began to paint such subjects as well. Baron 1979, p.146.

Rutherston wrote to his parents describing how his prize-winning painting was to be displayed alongside John’s and Orpen’s, November 1901, Tate Archive TAM 50.

Reproduced in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1983 (1).

Two early drawings by Gore, Pierrots: Commedia dell’Arte c.1900, and Two Ladies in White c.1900, reveal the influence of Goya but also appear to have also been influenced by Orpen’s studies for The Play Scene from ‘Hamlet’. See Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914: Drawings and Watercolours, exhibition catalogue, Davis and Langdale, New York 1990 (1 and 2), and Bruce Arnold, Orpen: Mirror to an Age, Jonathan Cape, London 1981, pp.67–9.

See Anna Gruetzner Robins, A Fragile Modernism: Whistler and his Impressionist Followers, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2007, pp.43–5 for examples of Whistler’s influence on domestic interior portraiture. Rothenstein recalled in his autobiography Men and Memories that what he called ‘small “interior” subjects’ were a distinctive group of works that he began in 1900; William Rothenstein, Men and Memories, vol.2, Faber and Faber, London 1932, p.2.

Gilman and Gore were described as the ‘“intimistes” of England’ by Frank Rutter in 1913. See Anna Gruetzner Robins, Modern Art in Britain 1910–1914, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1997, pp.117–20 on Bonnard’s and Vuillard’s importance to the Camden Town Group.

Reproduced in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London (96).

Baron observes that although Innes primarily painted romantic landscapes, at dates when he was in contact with members of the Camden Town Group in 1908 and again in 1911–12 he produced rare interiors and theatrical scenes. Baron 1979, no.48.

Rutherston introduced Sickert to Gore in 1904 on a painting trip in Normandy with Gore and Walter Westley Russell; Baron 1979, p.8.

Soon afterwards, Sickert organised an independent exhibition of these artists as the ‘London Impressionists’ at the Goupil Gallery in December 1889 which included work by Brown and Steer, and in 1891 he hosted Steer’s first solo show in his studio in Glebe Place. Baron 1979, p.5.

John first exhibited at the NEAC and held a solo show at the Carfax Gallery in 1899, the year after leaving the school. Orpen first exhibited at the NEAC in 1900 and held a solo show at the Carfax Gallery in 1901, having left the Slade in 1899.

The Camden Town Group artists’ engagement with realism is complex and both Sickert and Ginner were concerned to distinguish their ideas from naturalism, which they considered to be a direct transcription from nature without the transformation of the work by the artist’s individual sensibility (see note 9, above, for further discussion). Fry’s ‘An Essay in Aesthetics’, published in the New Quarterly in 1909, argued against the importance of studying from nature in favour of the emotional and aesthetic impact of the work: ‘The artist’s attitude to natural form is therefore infinitely various according to the emotions he wishes to arouse. ... We may, then, dispense once and for all with the idea of likeness to Nature, of correctness or incorrectness as a test, and consider only whether the emotional elements inherent in natural form are adequately discovered.’ These opposed ideas came to a head in the response to Fry’s two exhibitions of French post-impressionist painting. The subsequent debate about the impact of French post-impressionist painting in Britain has often been used to divide artists and critics into ‘traditionalist’ and ‘progressive’ groupings and to obscure the complexity of the debate that actually occurred.

Membership of Vanessa Bell’s Friday Club sometimes overlapped with the Fitzroy Street Group: John, Lamb and Innes attended both groups and Lightfoot joined this group rather than the Fitzroy Street Group upon leaving the Slade.

The Friday Club was started by Bell in 1905. Richard Shone, ‘The Friday Club’, Burlington Magazine, vol.117, no.866, May 1975, p.280.

Sickert, Russell and Rothenstein sat on NEAC juries and committees, Rutherston and Pissarro were members and Gore regularly exhibited there. Russell and Thompson both taught at the Slade, Russell as Assistant and Thompson as Lecturer in Perspective. Department of the Fine Arts: Slade School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, ‘Courses of Study’, College Calendar, University College London 1907–8.

Emma Chambers is Curator, Modern British Art, at Tate Britain, and formerly a curator at University College London Art Collections, which holds the collections of the Slade School of Fine Art.

How to cite

Emma Chambers, ‘Slade School Influences on the Camden Town Group 1896–1910’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www