Walter Sickert’s Drawing Practice and the Camden Town Ethos

Alistair Smith

Walter Sickert exhibited only a small number of drawings in his lifetime but drawing was an integral and crucial part of his practice. Alistair Smith considers Sickert’s methods and shows how his techniques influenced other Camden Town artists.

No drawings were included in the 2008 Tate Britain exhibition, Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group. In that respect it almost precisely mirrored the three exhibitions of the original Camden Town Group, which took place in 1911 and 1912.1 However, the Tate exhibition catalogue refers to the existence of preparatory studies for the majority of the paintings in the 2008 exhibition, confirming the importance of drawing in the practice of Walter Sickert and other members of the group. This brief study outlines how Sickert used drawings as essential tools towards the creation of his paintings. It also cites examples of how progressive members of the Camden Town Group both adopted his process and adapted it significantly to form a more consciously modern style.

Indeed, in the retrospective exhibition of Sickert’s work mounted at the National Gallery in 1941, of which, as his biographer Matthew Sturgis notes, Sickert was only ‘dimly aware ... through the haze of illness’,2 the place that drawings played within his artistic practice was recognised by the fact that they comprised a quarter of the items on show (33 of 132). A number of these were described in the exhibition catalogue as being studies for specific paintings, and a brief appendix stated that ‘Sickert has the habit of taking out old drawings and painting from them many years later’.3 During the artist’s lifetime, many of his drawings found their way into both private and public collections, but the real status of drawing within his artistic procedure remained largely unfathomed until after his death in 1942, when large numbers of sheets were found still in his possession. After the death of his widow, Thérèse Lessore, in 1945, the newly established Sickerts’ Trust, confronted by this embarrassment of riches, undertook to ‘augment the works of Sickert in the various collections of the British Isles and the Dominions’ with the result that, in the immediately ensuing years, hundreds of drawings were donated to public collections.4

It then became obvious that Sickert had exhibited only a very limited proportion of his drawings during his lifetime, and that, although the line of demarcation between working and finished drawings was fluid, those exhibited were principally works which would have been construed as having an appeal for collectors. These had well-defined subjects, whether architectural or narrative, and were relatively large. He retained in his possession those drawings which best served him as a basis for paintings and prints, and which were precise records of locations and events fundamental to his art.

This is not to say that Sickert had at all sought to hide the regularity with which he drew, nor the extent to which his paintings were dependent on his drawings. On the contrary, he was ever at pains to explain the nature of his drawing practice. He did this through the various schools which he founded over many years, through correspondence and conversation, through his public lectures and published criticism, and indeed through publishing drawings in journals.5 Despite these efforts, his drawings never received attention equal to that accorded his paintings, and it was not until 1949 when an Arts Council exhibition focused on the drawings which the Sickerts’ Trust had donated to the Walker Art Gallery that the true extent, range and, indeed, the character of Sickert’s drawing was brought to light.6

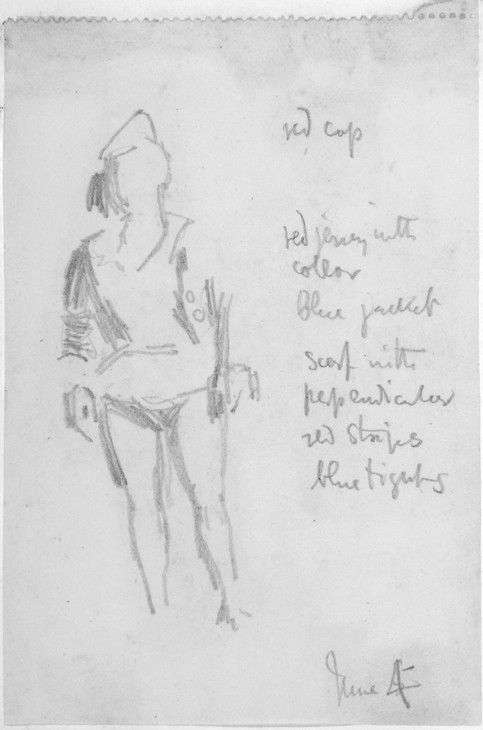

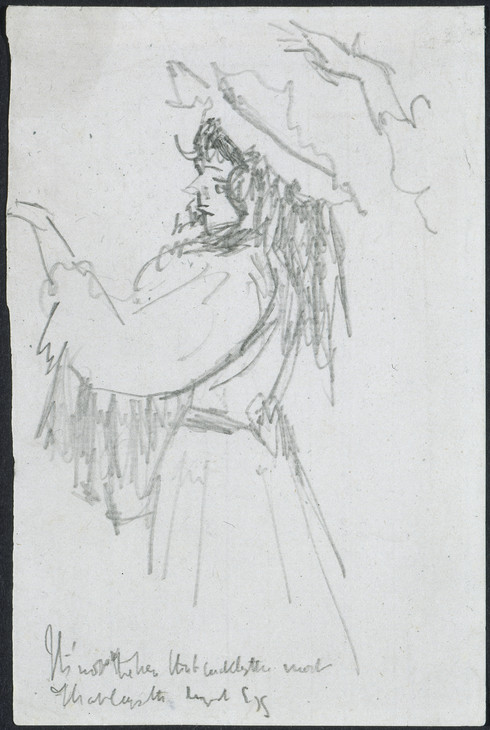

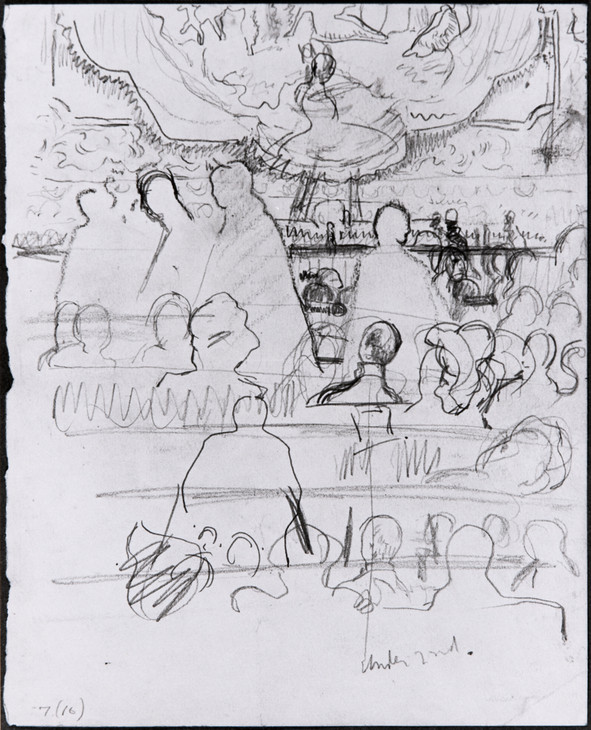

Many of the Walker drawings are tiny and would have been considered inappropriate for commercial exhibition. Yet Sickert kept many of them for sixty years. It was these that he took out and painted from years later, and it is these which give real insight into his artistic credo. His earliest extant drawings were made in sketchbooks small enough to fit into the palm of the hand, thereby allowing him to draw, unsuspected and unobserved, restaurant diners, theatre audiences, music-hall performers and whatever else took his fancy. Many were later mounted in groups, often focusing on a particular songstress, or documenting one particular evening of entertainment. That a considerable period might elapse before they were trimmed and mounted is attested by the vagueness of the annotations in Sickert’s hand, for example, ‘1881 or thereabouts | 1882 | 83? | 84?’.7 Sickert evolved his drawing technique to counteract the limitations imposed on him by the generally dark and fluctuating light of the music hall. The drawings are small, perhaps for secrecy, and generally in monochrome pencil (graphite), since the use of ink or wash would have been an encumbrance more likely to attract attention. Lacking the precision of colour, Sickert made tiny, but often surprisingly detailed, notes on his drawings, ‘narrow shadow along the bottom ... scarf ... button flashing’,8 ‘red cap | red jersey with | collar | blue jacket | scarf with | perpendicular | red stripes | blue tights | June 4 [corrected from “June 5”]’ (fig.1). And in his zeal to record as much as possible of the atmosphere of the moment, he would often write down the words of songs: ‘It’s not the hen that cackles the most | that lays the largest egg’ (fig.2).9

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Sketch of a Female Figure 1888

Pencil on paper

115 x 78 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Sketch of a Female Figure 1888

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

It's not the Hen that Cackles the Most that Lays the Largest Egg c.1892

Crayon and pencil on squared paper

150 x 98 mm

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

It's not the Hen that Cackles the Most that Lays the Largest Egg c.1892

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

Sickert evolved his method to record his chosen themes as exactly as he could, given the environmental limitations. In essence, he was attempting to create a document of photographic accuracy in situations where photography was still unfeasible, despite recent improvements in electric lighting. The perpetual movement of the performers and the ever-changing light meant that he had to be quick, and to the end of his life he was composing new metaphors for his swift and summary seizure of the motif. As he explained in a 1934 lecture at the Thanet School of Art:

There are three stages in drawing. First of all there is the tentative line which above all must be rapid. There is no sense in it not being rapid. You will make mistakes if you draw rapidly, but you will make ten times as many if you draw slowly. If you were shooting birds and you shot them slowly it would not be much good; you can only shoot them at all by shooting quickly.10

Most of the drawing techniques, which Sickert evolved specifically for the purpose of ‘drawing in the dark’, remained with him throughout his life. With considerable insistence he taught many others to follow his methods, and these were unusual enough for his pupils, assistants and friends to think them worthy of record. When, for example, he taught an art class in Manchester in the late 1920s, the process he recommended was documented in detail in a series of articles in the Manchester Guardian in 1930. The artist’s principal recommendations were summarised as follows:

he endeavoured to take his pupils back to the old traditions and cut out the modern abuses which, he claimed, had arisen with the spread of art schools ... the only satisfactory way of drawing was to draw to the visual size [or ‘sight size’].11

Sickert’s plan was, first of all, to go over all the ordinary outlines, bit by bit, once with a lightly drawn pencil, but always looking at the object and its background as part of the same design. Never sketch the picture and the background separately.

Then the shadows are added ... finally you go over the whole drawing again with the point of the pencil, giving the further corrections to the outline and the essential parts of the picture.

Sickert, of course, never allowed anyone to rub out. He claimed that the first impression, depicted by the first outline, was of great value and had a personal quality.12

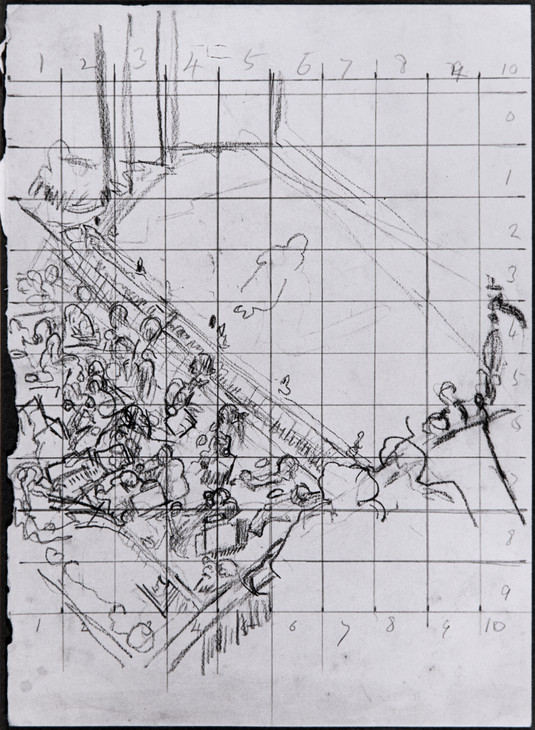

The second stage of Sickert’s instruction ‘concerned itself with the actual making of the picture’:

He showed us how to draw lines across our sketch, in the form of a draughtboard, with all the squares of uniform size, the size depending on the actual sketch and the amount of detail. Then taking a sheet of thin paper, drawing a similar set of squares, but multiplying the size by two, three or as many times as was necessary to cover a canvas of the ultimate size of the picture. We then had to draw in each square a copy of the portion of the drawing which we found in the corresponding small square in our original sketch. When this was finished we had a drawing of the necessary size, but all covered with squares.

In order to transfer this drawing to the canvas he advised us to get a sheet of newspaper, or some similar kind of paper, and paint it all over on one side with black oil paint; then place this paper, with the paint side downwards, on our canvas and fasten over it with drawing pins the new enlarged sketch. Then with a stylo trace over all the lines. When this was finished and the canvas uncovered, if it were properly done, we found our sketch transferred to the canvas in black outlines.13

Finally there came the colouring, when the student again referred back to the colour notes of tone value and local colour he or she had made on the original drawing.

‘The Sickert method’, as it was described, aimed at achieving the accurate transfer of the original drawing, preserving its qualities. As Sickert stipulated, ‘the man ... has got to be drawn. ... He has got to be drawn before the fizziness in his momentary mood has become still and flat.’14

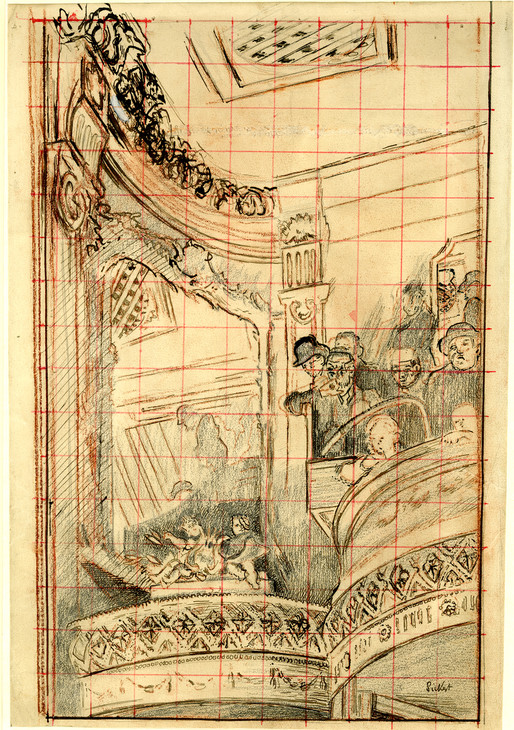

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Part of the Interior of the Old Bedford Music Hall c.1890

Pen and black ink with brown and black chalk and pencil on paper

420 x 289 mm

British Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Part of the Interior of the Old Bedford Music Hall c.1890

British Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

As Sickert made plain, the reliance on sight-size drawing from the motif and on the grid transfer technique were traditional methods used in Renaissance times but largely abandoned in the late Victorian art college.15 However, his abandonment of the subject matter of Victorian history painting in favour of ‘paintings of modern life’ endowed accurate transfer (via the grid) with the status of a sine qua non. Consequently, he was not loath to promote his beliefs to artists of some experience, including his colleagues in the Camden Town Group. The Tate Gallery director, John Rothenstein, later recounted that ‘During a visit to Dieppe in 1911, Sickert showed [Charles Ginner] how to work from squared-up drawings. After 1914 [Ginner] relied entirely on drawings of this character, accompanied by elaborate written colour notes, which he sometimes made by the use of a little homemade viewfinder.’16 Despite his adoption of the Sickert method, Ginner’s finished paintings and watercolours are determinedly different, endowed with what Sickert described as ‘burning patience’.17

It was the other two ‘Gs’ of the Camden Town Group, Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, who developed their painting in a more modern direction while still adhering to the general nature of Sickert’s procedure. Gore met Sickert in Dieppe in 1904 and John Rothenstein presumed that it was Sickert who infused him with his interest in the theatre and music hall. Gore, however, diverged from the detail of the Sickertian procedure, for example dispensing with secrecy and drawing openly using colour:

His method was to visit the theatre, always occupying the same seat, equipped with a small notebook, Conté chalk and a fountain pen [anathema to Sickert]. Thus stationed he would add a stroke or two, at the relevant moment, to a study of a transient pose or relationship of figures. A tightrope walker involved a succession of visits to capture a pose held only for an instant.18

His friend, the journalist Ashley Gibson, found something of a comic element in Gore’s concentration, remembering him ‘in the Alhambra balcony, always in the same seat, taking sights with thumb and pencil at the uplifted legs of the ballerinas’.19 Some of Gore’s drawings are indeed very like Sickert’s, but he was less pedantic about the need to use them in every situation and recommended painting directly from nature in certain instances (figs.4 and 5).20

Spencer Gore 1878–191

Music-hall study

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.4

Spencer Gore

Music-hall study

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Music-hall study

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.5

Spencer Gore

Music-hall study

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Gore and Gilman were both almost twenty years younger than Sickert, more positively attuned to the type of post-impressionist work that they had seen in Roger Fry’s exhibitions of 1910–11 and 1912, and more flexible in their response. As Ashley Gibson recalled, ‘Freddy [Gore] was extraordinarily interested in these new aesthetic portents, full of the legends he had been hearing about their originators, and thrilled me with the dreadful story of Van Gogh’s ear’.21 James Bolivar Manson also stated that ‘Gilman and Gore were in league, and interested in every aspect of art’.22 Despite this ideological detachment from Sickert, and the eventual personal dispute between him and Gilman, both Gore and Gilman continued to use the Sickertian grid but with alterations to the detail of the technique and, in Gilman’s case, a developed attitude to its significance.

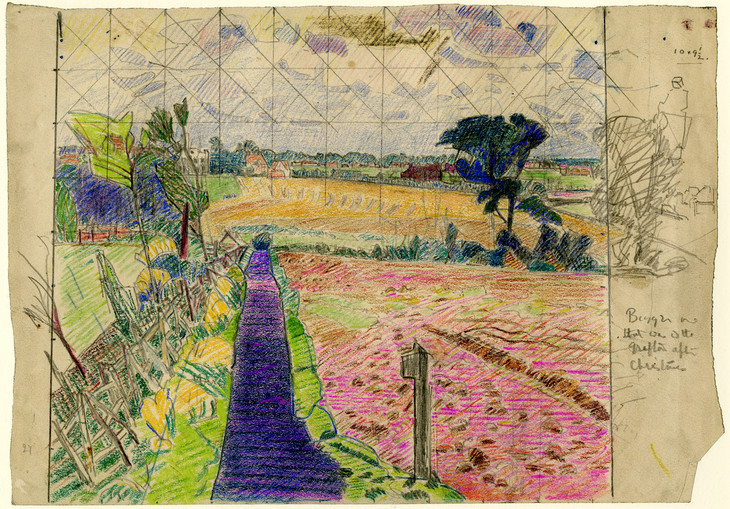

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Cinder Path 1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 686 x 787 mm; frame: 815 x 924 x 73 mm

Tate T01960

Purchased 1975

Fig.6

Spencer Gore

The Cinder Path 1912

Tate T01960

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'The Cinder Path' 1912

Coloured chalks and pencil on paper

235 x 332 mm

British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.7

Spencer Gore

Study for 'The Cinder Path' 1912

British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Interior with a Woman Sewing 1913 Study for ‘Norwegian Interior’

Black ink with red chalk and red-coloured pencil on paper

290 x 228 mm

British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.8

Harold Gilman

Interior with a Woman Sewing 1913 Study for ‘Norwegian Interior’

British Museum, London

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Gore made a number of preparatory drawings on the site of The Cinder Path on the outskirts of Letchworth, producing a painting which was advanced enough to be included in the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition of 1912 (fig.6). The most developed drawing for the composition shows Gore using a grid composed not only of squares but also of a diagonal, diamond-shaped mesh (fig.7). This technique was also used in a preparatory study by Gilman at around the same time (fig.8). In both cases the grid has the effect of flattening the appearance of the composition, effectively making the picture plane assume greater importance. As the art critic Rosalind Krauss has put it in one of her studies of grids in the hands of later twentieth-century modernists:

the grid is a way of abrogating the claims of natural objects to have an order peculiar to themselves ... Indeed, if it maps anything, it maps the surface of the painting itself ... the physical qualities of the surface, we should say, are mapped onto the aesthetic dimensions of the same surface.23

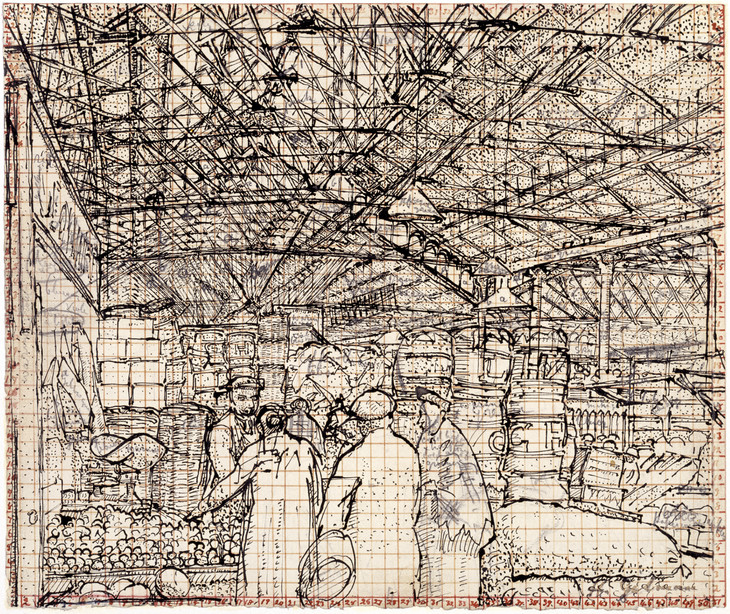

It is obvious from their painted work that Gore and Gilman were developing paintings with more planar, flattened compositions. These were perhaps originally suggested to Gore by the theatrical flats (flat pieces of wood painted to look like buildings or furniture) which form an important part of his stage scenes, as much as by the example of works by Cézanne seen in the post-impressionist exhibitions. But Gore and Gilman’s method of imposing such a pronounced visual overlay on their drawings clearly contributed to their habit of seeing the world in a more planar and geometric way. Their compositions become infused with flat, rectangular façades placed full-face to the picture plane; their description of objects also tends more to the abstract (figs.9 and 10). Gilman, in particular, developed an incipiently geometric aesthetic based on industrial architecture; the background in his Leeds Market, for example, becoming the ultimate development of Sickert’s transfer grid (figs.11 and 12).

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Harold Gilman's House at Letchworth 1912

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 760 mm

Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Photo © Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Fig.9

Spencer Gore

Harold Gilman's House at Letchworth 1912

Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Photo © Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 464 x 615 mm; frame: 666 x 816 x 83 mm

Tate N03684

Purchased 1922

Fig.10

Harold Gilman

Canal Bridge, Flekkefjord c.1913

Tate N03684

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Study for 'Leeds Market' c.1913

Ink and pencil on paper

support: 250 x 297 mm

Tate T00143

Purchased 1957

Fig.11

Harold Gilman

Study for 'Leeds Market' c.1913

Tate T00143

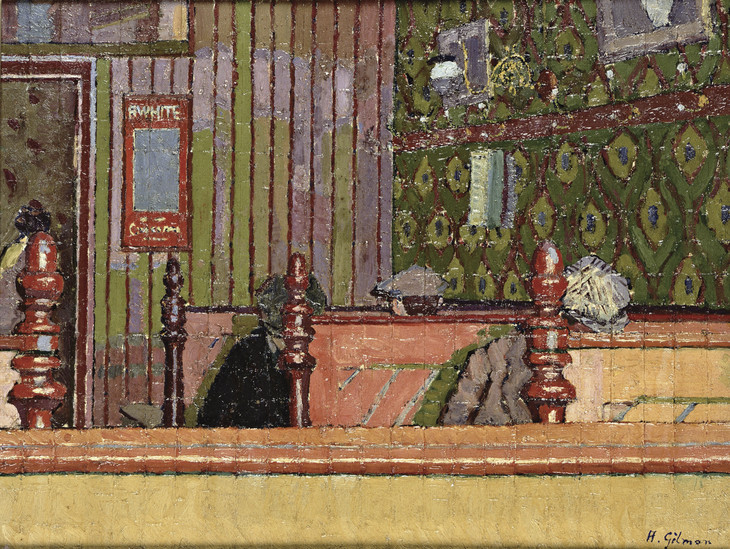

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Leeds Market c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 610 mm; frame: 690 x 790 x 75 mm

Tate N04273

Presented by the Very Rev. E. Milner-White 1927

Fig.12

Harold Gilman

Leeds Market c.1913

Tate N04273

Gilman’s most radical development of the Sickertian transfer grid takes the form of his painting An Eating House. It exists in two versions. The larger version (fig.13) is distinguished from the smaller by the grid of small squares which covers its surface, their edges defined by raised areas of paint.24 It has often been suggested that this grid was used to transfer the compositional design either to, or from, the smaller version.25 This is clearly true, since the squares on the large version number eighteen vertically and twenty-four horizontally, and the small version measures eighteen by twenty-four inches. This canvas size was regularly used by Gilman, which suggests that the small version was the first to be painted, and that Gilman transferred the design in the Sickertian manner to make the larger version. However, in the finished painting the transfer grid would have been covered by the paint layer and invisible beneath it. The method of transfer could not have contributed to the meticulous square ridges of raised paint which cover the large version. They add a rigorous geometric component to a composition already defined by the verticals (of the eating-house’s panelled background) and the horizontals (of the booths).

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

An Eating House c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

572 x 749 mm

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.13

Harold Gilman

An Eating House c.1913–14

Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust

Photo © Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Although developed from the transfer grid adopted by most of the Camden Town Group, Gilman’s overt display of it as an enlivened surface to this painting is unique within the work of the group, and the source of his inspiration seems to have been equally individual. The grid on the surface of An Eating House is not intended to convey impressions of speed, movement and dynamism which futurist faceting evoked. His inspiration, rather, seems to lie in the work of the French authors that his friend and painting companion Hubert Wellington referred to when introducing an exhibition of Gilman’s work in 1943: ‘He liked the writings of Jules Romains, Charles Vildrac and the “Unanimiste” Group in France for their parallel interests.’28 Briefly, unanimism was the literary exploration of the unity of groups as distinct from the dynamics of the individual. The French writer Jules Romains was interested in the new kinds of group life that resulted from the spread of cities. The eating-house, as depicted by Gilman, is one example of that new sociology. It shows one of the new, not-for-profit eating-houses which aimed to provide decent food for the urban poor. They were promoted by temperance societies and directly opposed to the music-hall culture which Sickert celebrated. (Notice, for example, the advertisement for an R. White’s non-alcoholic and health-promoting squash on the panelling in the background.) In Gilman’s painting, individuals are undifferentiated and defined as a group. Indeed they are merged together by the subtly faceted grid which unifies the composition in an overtly modern geometric manner. Gilman developed Sickert’s utilitarian transfer grid and combined it with his bright, positive colour, to express an optimistic view of new groupings in modern society, extending the essential ethos of Camden Town form and subject matter.29

Notes

A few drawings by Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, John Doman Turner and Henry Lamb were included in these exhibitions although none by the core Camden Town Group artists. However, Sickert’s solo shows at the Carfax in 1911 and 1912 focused strongly on drawings. See Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Aldershot 1996, pp.85–93. The author is grateful to Emma Chambers for this reminder.

Louise Powell, ‘Introduction’, in A Brief Record of the Sickerts’ Trust and its Work During the Years 1946–1950, London 1951.

See essays by Anna Gruetzner Robins, Wendy Baron, Nicola Moorby and Alistair Smith in Walter Sickert: ‘drawing is the thing’, exhibition catalogue, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester 2004.

Notes and Sketches by Sickert from the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1949.

Inscribed on the backing mount of Four Restaurant Studies, Leeds City Art Gallery, accession no.14.331/47; reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004 (1.01).

Eighteen Drawings, Leeds City Art Gallery, accession no.14.336/47; reproduced in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004 (1.04).

Walter Sickert, ‘Colour Study: Importance of Scale’, lecture at the Thanet School of Art, Margate, 16 November 1934, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.653.

‘Pictures by Mr Sickert’s Pupils: A Manchester Exhibition’, Manchester Guardian, 18 October 1930; quoted in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004, p.23.

‘A correspondent’, ‘Sickert’s Methods: The Teaching of Drawing’, Manchester Guardian, 27 October 1930; quoted in Whitworth Art Gallery 2004, p.23.

Walter Sickert, ‘Schools of Art’, Speaker, 23 January 1897, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.131–3. Sickert returned to the theme on occasions too numerous to quote in this short article.

Walter Sickert, ‘A Monthly Chronicle’, Burlington Magazine, January 1916, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.401.

J.B. Manson reported speech in John Woodeson, Spencer F. Gore, unpublished MA thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, London 1968, p.108.

Rosalind E. Krauss, ‘Grids’, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge MA and London 1994, pp.50–2.

The smaller version is owned by Richard Burrows and reproduced in Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981 (49).

See, for example, ibid. Gilman and Ginner exhibited together at the Goupil Gallery, London, from 18 April to 9 May 1914, when No.1, Gilman’s The Eating House, was priced at £25, and No.5, his An Eating House, at £30. This gives further reason to deduce that No.5 was the larger and later version.

Hubert Wellington, ‘Introduction’, in Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Alex, Reid and Lefevre, London, September 1943.

Alistair Smith is an independent scholar and former Director of the Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester.

How to cite

Alistair Smith, ‘Walter Sickert’s Drawing Practice and the Camden Town Ethos’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www