Photo by Lily Vetch

Photo by Lily Vetch

Photo by Lily Vetch

Except for three years by the Sussex seaside, William Blake spent his entire life in London. He was born in Soho in 1757. Nearly 70 years later, he died in a location just off the Strand. Most famously, London appears in Blake's poetry collection, Songs of Experience, as the scene of exploitation and social injustice. Though he hated the misery and darkness of the city, it was only in London, he wrote, that he could 'carry on his visionary studies... see visions, dream dreams.'

Discover the city landmarks and locations that meant most to the artist in our tour around Blake's London.

Broad Street

Commemorative plaque, William Blake House, Broadwick Street

Broadwick Street, London

Photo by Lily Vetch

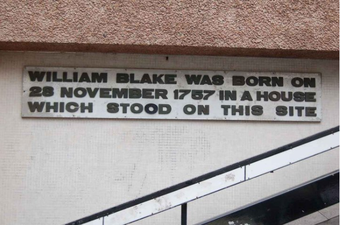

On 28 November 1757 Blake was born at 28 Broad Street, Soho. His father ran a successful hosiery shop in the ground floor of the same building. Soho then lay on the extreme northern edge of London with nothing but fields and market gardens beyond. The young Blake was able to roam freely in the countryside.

Blake remained at 28 Broad Street until 1782, when he moved out to Green Street with his new wife, Catherine.

When Blake's father died in 1784, his eldest son James took over the hosiery business. Blake moved nextdoor, where he set up as a print seller in partnership with James Parker, an expert in mezzotint.

Twenty-five years later, the hosiery shop's first floor was the unlikely site of Blake’s only solo exhibition. The show was not a success.

27 and 28 Broad Street no longer survive. The street has been renamed Broadwick Street, and there is now a block of high rise apartments on the site, William Blake House. Old houses that survive on Broadwick Street, however, give a good idea of what Blake’s house looked like.

St. James's Church

St James's Church, Piccadilly

Photo by Lily Vetch

St James's Church, Piccadilly

Photo by Lily Vetch

Blake was christened in this church built by Christopher Wren on 11 December 1757. By rights, however, the ceremony should have taken place in the Blakes’ own parish church of St. Anne’s Soho on Wardour Street. St. James’s was in the next-door parish of Westminster.

Ironically, the church is diagonally opposite the philosopher Isaac Newton's former residence in Jermyn Street. Blake scorned Newton for ignoring the spiritual in his philosophy.

Mr. Pars's Drawing School, The Strand

Agar Street

Photo by Lily Vetch

In 1767, at the age of 10, Blake was sent to Mr. Pars’s drawing school. He stayed here for four years, copying plaster-casts.

Pars's drawing school was located on the North Side of the Strand in Castle Court. The address no longer exists, as the court was demolished during the Regency.

The school stood on what is now the corner of Agar Street and King William Street.

31 Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn

Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn

Photo by Lily Vetch

Blake’s father was not able to afford to send him to be taught by a great painter. So, in 1771 and at the age of 14, Blake was apprenticed to the engraver, James Basire of Queen Street. Engraving – which was then a booming trade – seemed to offer a better chance of earning a steady living than painting. Blake remained with Basire for seven years.

The original building where the workshop was located was demolished in the late nineteenth century, but the next-door houses (of brick rather than stone) give an idea of its original appearance.

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

Photo by Lily Vetch

Basire was official engraver to the Society of Antiquaries. As a result, Blake was sent to old churches to draw ancient tombs and monuments. An enthusiastic Blake is said to have climbed onto the tombs in Westminster Abbery in order to draw them better.

Working in Westminster Abbey made Blake a passionate admirer of the then neglected gothic aesthetic. This contributed to his indifference to the standards of fashionable art of his time. It inspired him to produce his early history paintings (such as The Penance of Jane Shore), and also led him to create a unique philosophy that blended religion, history and politics.

There is a monument to William Blake in Poet’s Corner in the Abbey, added in 1957.

Royal Society of Arts

Royal Society of Arts

Photo by Lily Vetch

Royal Society of Arts

Photo by Lily Vetch

The Royal Society of Arts features a series of murals entitled The Progress of Human Knowledge and Culture. These were painted between 1777 and 1784 by James Barry.

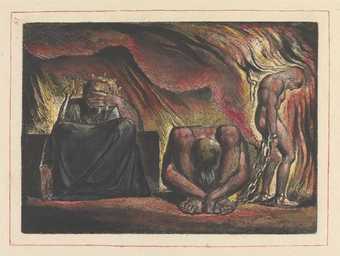

Barry was Blake's teacher when he was a student at the Royal Academy. Blake admired Barry’s grand, heroic canvases, which depicted historical or poetic subjects. There are clear similarities between Barry’s King Lear Weeping Over the Dead Body of Cordelia and Blake’s numerous bearded prophets and deities, such as in Ancient of Days. Blake felt great kinship with Barry. They were both outsiders and both stubbornly refused to bow to the fashions of the time.

Royal Academy

Somerset House, the former location of the Royal Academy

Photo by Lily Vetch

The Royal Academy was founded in December 1768. Sir Joshua Reynolds, the celebrated portraitist, was its first president. The Academy was originally located in Old Somerset House, but moved to New Somerset House in 1780. It is now located in Burlington House on Piccadilly.

Blake was admitted as a student to the Academy in August 1779. He took the usual courses, but also worked as a commercial engraver while studying. Blake exhibited his work at the Academy on several occasions, 1808 being the last.

In the 1790s there may have been a movement to make Blake a member of the Royal Academy. Despite the support of successful artists like Benjamin West and Richard Cosway, the ‘eccentricity’ and ‘extravagance’ of his designs, and a snobbish prejudice against the humble birth of his wife, probably ruined his chances. In the 1820s Blake was granted twenty-five pounds by the Academy on the grounds that he was ‘laboring under great distress’.

William Blake

The Good and Evil Angels (1795–?c.1805)

Tate

Green Street, Leicester Square

Irving Street

Photo by Lily Vetch

Irving Street

Photo by Lily Vetch

After his marriage in 1782, Blake moved out of the parental home in Broad Street to lodgings in Green Street, off the south-east corner of Leicester Square. Blake's first biographer, Alexander Gilchrist claimed that Blake’s father drove him from the house, angered by his marriage to an uneducated woman.

In the late eighteenth century Leicester Square was a fashionable residence for artists, and both William Hogarth and Sir Joshua Reynolds had lived there. Blake and Catherine lived here for just two years before returning to Broad Street. Green Street no longer exists, and this picture shows nothing more than the approximate former site of Blake’s residence.

28 Poland Street

Poland Street

Photo by Lily Vetch

After Blake dissolved his partnership as a print seller with James Parker he moved from Broad Street to 28 Poland Street. It was, according to his biographer Peter Ackroyd, ‘a narrow house of four storeys and a basement, with a single front and back room on each floor’. Blake lived here until 1791, when he moved to Lambeth.

It was at 28 Poland Street that William Blake invented his revolutionary printmaking technique. This allowed him to combine text with image and create the works that have come to define him. The house was rebuilt in the late nineteenth century.

Hercules Buildings

A plaque memorialising Blake's former home on Hercules Street

Photo by Lily Vetch

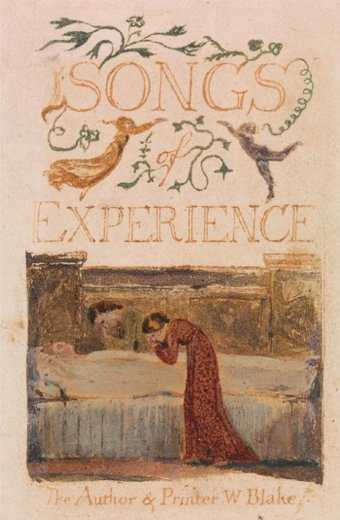

Blake lived at 13 Hercules Buildings, Lambeth from 1791 until 1800. It was in this house that he produced the Songs of Experience, Europe and America (and other prophetic books), and the series of twelve watercolours that includes Newton and Nebuchadnezzar.

The house, which was demolished in 1918, was one of the largest in a row of twenty-four, with a garden at front and back. It stood three storeys high and had eight or ten rooms. Blake worked in the front and back rooms on the first floor.

Lambeth was a pleasant rural area when Blake arrived. However, as legislation drove more industry across the river, it quickly changed into a noisy, disease-infested slum. It was very much akin to the London described in Blake’s famous poem.

William Blake

Nebuchadnezzar (1795–c.1805)

Tate

17 South Molton Street

A plaque memorialising where Blake lived on South Molton Street, London

Photo by Lily Vetch

Between 1800 and 1803 Blake lived in the Sussex seaside village of Felpham. Eventually tired of his patron William Hayley, who also lived there, and worried by an impending trial for sedition, Blake returned eagerly to London. The location of this new residence – close to Tyburn (now Marble Arch) where public hangings took place – was significant to Blake who makes reference to ‘Tyburn’s tree’ and ‘Tyburn’s brook’ in his prophetic book Jerusalem.

Sadly Blake’s optimism about his return to London was unjustified. Before setting out from Felpham he had written ‘My heart is full of futurity… I rejoice and tremble’. However, in the years he lived in South Molton Street he suffered his most bitter disappointments. Fame and financial success continued to elude him, and he sank into poverty and paranoia.

Fountain Court

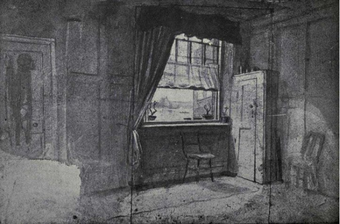

The room at number 3 Fountain Court where William Blake lived, worked and died

Coal House Tavern, The Strand

Photo by Lily Vetch

Blake lived in two rooms on the first floor of 3 Fountain Court, a red brick house, from 1821 until his death in 1827.

He was very poor, and frankly admitted that ‘he lived in a hole’. He consoled himself, however, with the thought that ‘God had a beautiful mansion for him elsewhere’. It was here that Blake produced his Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy and The Book of Job.

Fountain Court no longer exists, but was just situated behind the Coal Hole Tavern on the Strand. From the steps behind the Tavern you can enjoy a view of the Thames, described by Blake as looking like ‘a bar of gold’.

St Mary's Church, Battersea

St Mary's Church, Battersea

Photo by Lily Vetch

Blake married Catherine Boucher here on 17 August, 1782. Boucher, whose family lived nearby, was twenty-one at the time. Blake was twenty-five. They remained married for forty-five years until Blake’s death.

Despite having almost no education (Boucher signed her name as an X in the parish register) she was much more than a prudent housekeeper for Blake, helping him out with his engravings.

On his deathbed, Blake cried out to her ‘Stay! Keep as you are! You have ever been an angel to me’, before drawing her portrait for the last time. Boucher outlived her husband by a number of years, dying in 1831. She is buried in Bunhill Fields.

Bunhill Fields

Grave stone close to the spot where William and Catherine Blake are buried, Bunhill Fields Burial Ground

Photo by Lily Vetch

Blake died on 12 August 1827, and was buried at Bunhill Fields on the following Friday. Blake’s father and beloved brother Robert had also been buried there, as had the writers John Bunyan and Daniel Defoe. Blake was buried in an unmarked grave. A new monument to Blake, designed by Lida Cardozo, was unveiled in Bunhill Fields in 2018.

Paolozzi's Newton, British Library

Eduardo Paolozzi's sculpture of Newton outside the British Library

Photo by Lily Vetch

William Blake

Newton (1795–c.1805)

Tate

Set in front of the British Library on the Euston Road, this statue by artist Eduardo Paolozzi is modeled on Blake’s Newton, from the series of 12 large watercolours produced in the mid–1790s.

To the eighteenth century, Newton represented the triumph of rational thought. He was seen as bringing order to the universe. However, Blake could not forgive Newton for omitting a spiritual dimension from his theories. In a poem addressed to his patron Thomas Butts, Blake concluded:

May God us keep

From single vision and Newton’s sleep.