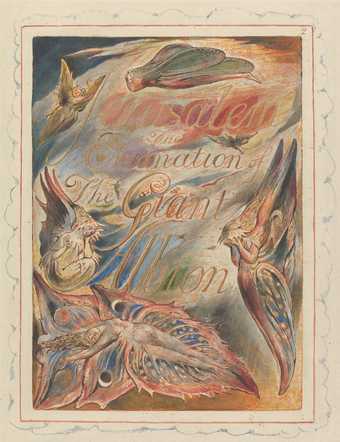

William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 2, Title Page 1804–20

Copy E, plate 2

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

At over 4500 lines, Jerusalem is the longest and the most magnificent of Blake’s illuminated books – but it is also perhaps his most mysterious. His first biographer called the poem as ‘a chaos of words, names and images’.

Blake worked on Jerusalem from 1804 to 1820, a period during which Britain was mostly at war with France. He thought it as his masterpiece. Believing that ‘poetry fetter’d, fetters the human race’, he composed Jerusalem in unrhymed free verse. Only five copies of the poem exist, of which only one is in colour.

In Jerusalem, Albion (England) is infected with a ‘soul disease’ and her ‘mountains run with blood’ as a consequence of the Napoleonic wars. Religion exists only to help monarchy and clergy exploit the lower classes. Greed and war have obscured the true message of religion. However, if Albion can be reunited with Jerusalem, the story goes, then all humanity will once again be bound together with love.

Look closer at five of the one hundred plates of Jerusalem, and read summaries and analyses of each one.

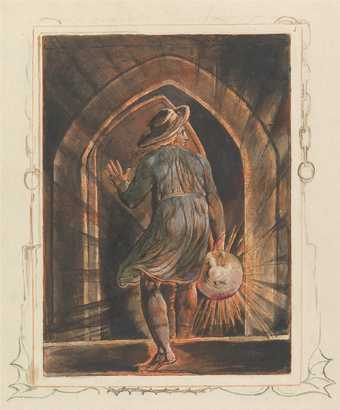

Frontispiece, Los Entering a Gothic Arch

William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 1, Frontispiece, 1804 to 1820

Bentley Copy E

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

This is the first of the one hundred plates that make up Jerusalem. It shows Los, the personification of the poetic imagination, passing through a gothic arch. Los is dressed like a London night watchman, but his sandals strike an anachronistic note, marking him out as a prophetic figure. On closer inspection the lantern in his right hand turns out to be a miniature sun, as described in Blake’s lines ‘Los took his globe of fire to search the interior of Albion’s bosom’.

For Blake, the Gothic (Westminster Abbey) represented true religion, while the Baroque (St Paul’s) symbolised the empty forms of state religion. (Compare Jerusalem, Plate 84). Here then the gothic arch represents truth.

On a simpler level, the door represents the beginning of the poem, while the austere greys and browns of the stone wall serve to increase the shock and excitement of the brilliantly colourful plates that follow.

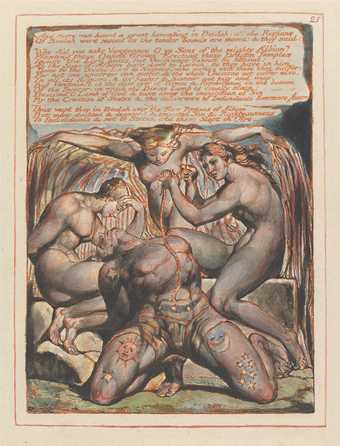

Plate 25, Albion and his Tormentors

William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 25, 'And there was heard....', 1804 to 1820

Bentley Copy E

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

In Jerusalem Druidic religion, with its rituals of human sacrifice, represents the cruelty and aggression of England. For Blake, the campaigns then being waged by his countrymen against Napoleon’s France were the contemporary expression of that savage, warlike spirit.

Here Albion (England) is the victim of Druid sacrifice, and is being disembowelled by three women, Rahab, Vala and Tirzah. Seated on the right, Tirzah cries as she winds Albion’s intestines into a ball in her hand.

The scholar Morton D. Paley believes that the scene depicts these lines from plate 66:

They sit naked upon the Stone of trial

The knife of flint passes over the howling victim: his blood

Gushes & stains the fair side of the fair Daughters of Albion

or these lines from plate 67:

Tirzah sits weeping to hear the shrieks of the dying: Her knife

Of flint is in her hand: she passes it over the howling victim.

Notice that the posture of Albion is almost identical to that of the man being stoned in Blake’s Blasphemer.

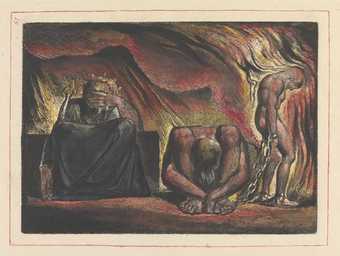

Plate 51, Vala, Hyle and Skofeld

William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 51, 1804 to 1820

Bentley Copy E

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Jerusalem consists of 100 plates or pages. It is divided into four sections of around twenty-five pages, each one addressed to a different audience – the Public, the Jews, the Deists, and the Christians. In between these different sections come four text-free illustrated plates like the one shown here. This page comes from the start of the third section, addressed to the Deists.

The picture shows (from left to right) Vala, Goddess of Nature, Hyle, one of the giant Sons of Albion, and ‘Skofeld’. The last of these three is the most interesting, since we can see how Blake took his revenge on people who had crossed him by inserting them into his private mythology. ‘Skofeld’ is, in fact, Private John Schofield, the soldier who, after being expelled by Blake from his Sussex garden, claimed that Blake had made disparaging remarks about the King and the British army, causing him to be tried for sedition in 1804. The scholar Morton D. Paley points out that Schofield, burning in hell-fire, is also weighed down by ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ of the kind we saw in London, in the Songs of Experience, while his posture resembles that of the personification of Despair in The House of Death.

The other real-life figures who play a significant role in Jerusalem are the Hunt brothers, journalists who had reviewed Blake’s work with brutal contempt.

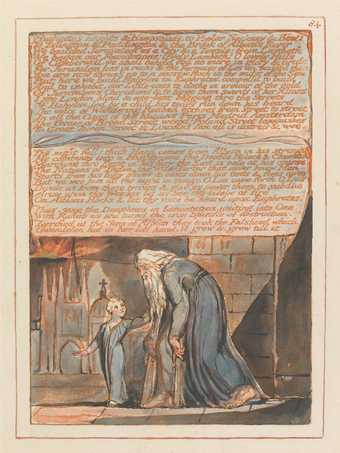

Plate 84, London led by a Child

William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 84, 'Highgates heights & Hampstead....' 1804 to 1820

Bentley Copy E

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The light falls dramatically on a child leading a bearded old man on crutches past a domed church towards a Gothic abbey, as the sun sets behind a distant hill.

This design illustrates lines 11–12 of plate 84:

I see London, blind & age-bent begging through the streets / Of Babylon, led by a child, his tears run down his beard.

In fact, this design (though reversed) is identical to that for the poem London in Songs of Experience. The scholar Morton D. Paley observes that the baroque dome of St Paul’s (which the two characters pass by) signifies the hollowness of established religion, while the Gothic Westminster Abbey, their final destination, represents true religion.

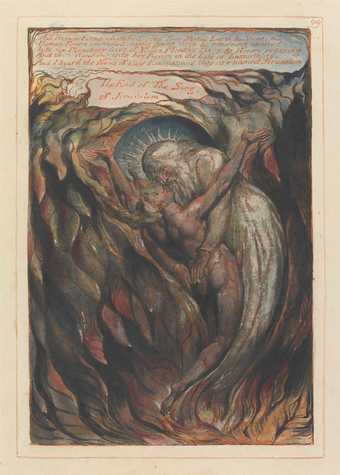

Plate 99, Jehovah embraces Jerusalem

William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 99, 'All Human Forms identified....', 1804 to 1820

Bentley Copy E

© Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

This is the penultimate plate of the whole Jerusalem series, and the man and woman embracing among dark flames is appropriately climactic. The picture illustrates the penultimate line of the whole poem:

Awaking into his bosom in the Life of Immortality.

Most commentators agree that the bearded old man is Jehovah, while the woman is Jerusalem. The image can be read as a message of universal reconciliation. The scholar Morton D. Paley points out the resemblance between Blake’s design and the Flemish artist Martin De Vos’s engraving of the Prodigal Son. According to the artist Samuel Palmer (a friend of Blake) this was ‘a story that Blake particularly loved and could not read without tears coming to his eyes’.