William Blake

The Good and Evil Angels (1795–?c.1805)

Tate

In his book Jerusalem, Blake famously wrote 'I must create a system, or be enslav'd by another man's. I will not reason & compare: my business is to create.' So while other poets might be content to use characters from the Bible, or from Greek and Roman myth, Blake created his own mythology populated by a host of beings that he himself had either invented, or re-interpreted.

Find out more about the characters that appear often in Blake's work.

Albion

William Blake

Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion 1804–21

Copy A, plate 37 © Trustees of the British Museum

This picture, the thirty-seventh plate of Jerusalem, shows Albion in despair. Albion is a poetic name for England. Taken from the Latin adjective ‘albus’ (white) it refers to the white cliffs of Dover.

Albion is occasionally presented as joyful figure, but he is most often depicted sleeping, suffering or in despair. In Blake's book Milton, Albion is asleep, ‘heavy and dull’ until Blake and Milton awaken his revolutionary fervour, while Jerusalem tells the story of the regeneration of Albion from harshness and cruelty.

Enitharmon

William Blake

The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (formerly called ‘Hecate’) (c.1795)

Tate

Enitharmon is an important female character in Blake’s mythology, playing a main part in some of his prophetic books. She is the Emanation of Los, and with Los gives birth to various children, including Orc.

Although symbolising spiritual beauty and poetic inspiration (some critics have argued that Blake’s wife Catherine was the inspiration for the character) she is also used by Blake to represent female domination and sexual restraints that limit the artistic imagination. The bulk of Europe a Prophecy is devoted to Enitharmon’s domination of the material world and puts forward various sexual rules through religion which Blake describes as errors found in orthodox Christianity.

The name ‘Enitharmon’ could be a derivation of (z)enit(h)-harmon(y). It has also been suggested that the Greek anarithmon or ‘numberless’ is another possible starting point for the name.

The Ghost of a Flea

William Blake

The Ghost of a Flea (c.1819–20)

Tate

John Varley was a watercolourist, landscape designer and astrologer whom Blake met towards the end of his life. Varley encouraged Blake to sketch portraits of the people who populated his visions, and in all there are between forty or fifty drawings of these characters. Many of these depict historical characters, like kings and queens, but the most popular has always been the flea, which exists both as a simple sketch and as this elaborate painting.

According to Blake, the story goes that fleas were inhabited by the souls of bloodthirsty men. These bloodthirsty men were confined to the bodies of small insects, because if they were the size of horses, they would drink so much blood that most of the country would be depopulated. The flea’s bloodthirsty nature can be seen in its tongue, darting from its mouth, and the cup (for blood-drinking) that it is carrying.

The poor quality of this picture is due to Blake painting it in what he called ‘fresco’ (tempera), which has cracked and dulled with age. The influence of Michelangelo (1475–1564), a Renaissance artist whom Blake admired, can be seen in the highly defined musculature of the flea’s burly body.

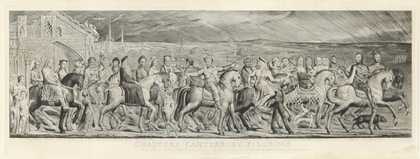

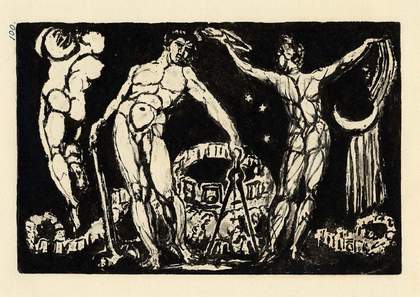

Los

William Blake, Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion 1804–21

Copy A, plate 100

© Trustees of the British Museum

This picture, the 100th and final plate from Jerusalem, shows Los (the middle figure) in the pose of the Apollo Belvedere. He is holding a hammer in his right hand, and a pair of tongs in his left.

In Blake’s mythology Los represents the imagination, and corresponds to the loving and forgiving Christ of the New Testament. (As opposed to Urizen who, according to Blake, is the vengeful and repressive God of the Old Testament). Los often appears as a blacksmith with the tools of his trade. Blake sees Los crafting objects from molten metal, as he himself forged his visions and inspirations into poetry and art.

The name ‘Los’ may derive from the word ‘loss’, alluding to fallen man’s having ‘lost’ Paradise. It may, however, be a reversal of the Latin word ‘Sol’ (sun), since Los is shown creating the sun on plate 73 of Jerusalem. On the right of the picture is Enitharmon, Los’s wife. To Blake, she represents misguided religion based on chastity and vengeance. Their child is Orc, the symbol of revolution.

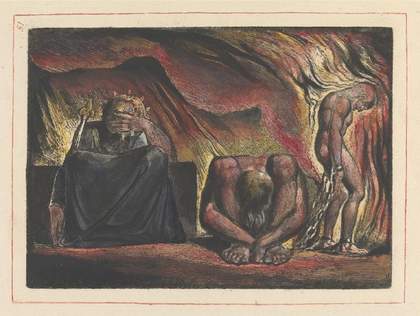

Nebuchadnezzar

William Blake

Nebuchadnezzar (1795–c.1805)

Tate

Nebuchanezzar was the King of Babylon whose arrogance was punished by God. This is how he is described in the Old Testament’s Book of Daniel:

He was driven from among men, and ate grass like an ox. And his body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hair grew as long as eagles’ feathers, and his nails were like birds’ claws

Here we see him in exile, animal-like on all fours. Naked, he gazes with horror at his own reflection. This picture was painted in 1795, two years after the execution of Louis XVI in France. Meanwhile in England, George III, whose control the American colonists had recently thrown off, suffered from bouts of insanity. Could this picture of a degraded king be an expression of Blake’s sympathy for the republicans in France and America?

Newton

William Blake

Newton (1795–c.1805)

Tate

The eighteenth-century poet, Alexander Pope, wrote a satirical epitaph for Newton:

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night

God said Let Newton be! And all was light.

This shows just how much the eighteenth century revered the great philosopher. Newton had successfully explained the workings of the physical universe. To Blake, however, this was not enough: Newton had omitted God, as well as all those significant emotional and spiritual elements which cannot be quantified, from his theories. Blake boasted that he had ‘fourfold vision’ while Newton with his ‘single vision’ was as good as asleep. To Blake, figures like Newton, Bacon and Locke with their emphasis on reason were nothing more than ‘the three great teachers of atheism, or Satan’s Doctrine.’

In this print from 1795 Newton is portrayed drawing with a pair of compasses. Compasses were a traditional symbol of God, ‘architect of the universe’, but notice how the picture progresses from brightness and colour on the left, to sterility and blackness on the right. In Blake’s view Newton brings not light, but night.

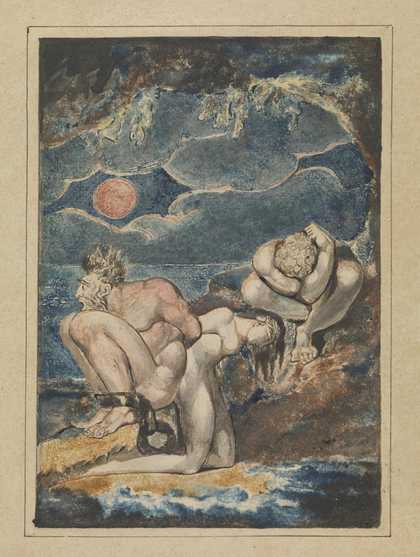

Oothoon

William Blake

Frontispiece to ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’ (c.1795)

Tate

This picture is the frontispiece of Visions of the Daughters of Albion. It shows (from right to left) Bromion, Oothoon and Theotormon.

Bromion (whose name means ‘roar’ or ‘inarticulate sound’ in Greek) has raped Oothoon, but they are now bound back to back. Oothoon represents both innocent sexuality and the political freedom. She is in love with Theotormon who returns her love, but is unable to act, considering her ruined. In the picture he is literally bending himself into knots of indecision. His name derives from ‘theo’ (god) and ‘torment’ or ‘torah’ (Hebrew law), and he represents man tortured by the restrictions of conventional morality.

In this poem the Daughters of Albion are a species of chorus who do little more than ‘weep’ and ‘sigh towards America.' They represent monarchy-oppressed Britain’s yearning for liberty. The doomed love scenario of Oothoon and Theotormon may derive from a book that Blake was illustrating at this time, about the adventures of an English captain who had experienced an ill-fated passion for a slave in the South American colony of Dutch Guiana.

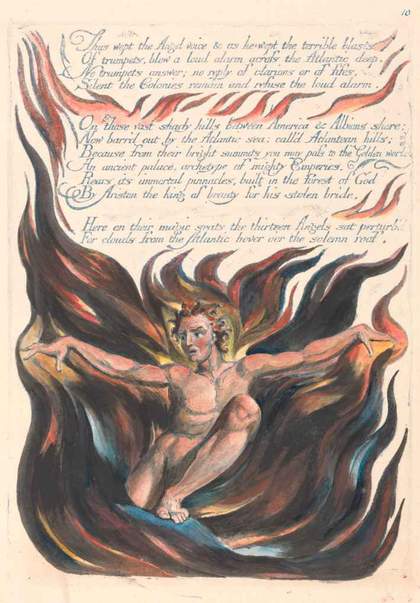

Orc

William Blake

America. A Prophecy, 'Thus Wept the Angel Voice....' 1793

Bentley Cop M, Plate 12

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

In America: A Prophecy, Orc is described as ‘Lover of Wild Rebellion, and transgressor of God’s Law.’ He symbolises the spirit of rebellion and the love of freedom which provoked the American War of Independence and the French Revolution.

Orc appears in four of Blake’s prophetic books: America, Europe, The Book of Urizen and The Four Zoas. In contrast to Urizen, a bearded old man who represents law and repression, Orc is a vigorous youth, surrounded by the fires of revolutionary passion and unrepressed lust. The scholar Foster Damon believes that the name Orc derives either from Cor (the Latin word for heart), or from Orca, meaning ‘whale.’

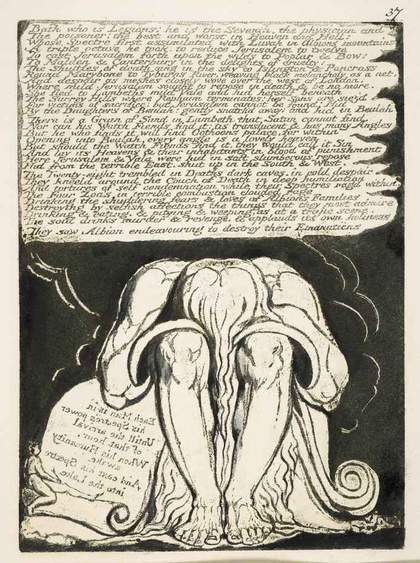

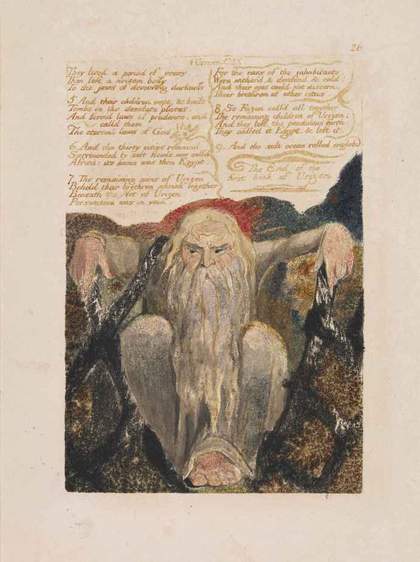

Urizen

William Blake

The First Book of Urizen 1794

Copy D, plate 26

© Trustees of the British Museum

There are two possible derivations of the name Urizen. It comes either from ‘Your Reason’ (meaning ‘accepted wisdom’ – accepted by everyone, but not by Blake), or from the Greek verb ‘horizein’, meaning ‘to limit’. Urizen is always represented as a bearded old man. Sometimes he bears books of divine law, sometimes measuring instruments (with which to create, but also limit the universe.)

Urizen is the God of the Old Testament who, in alliance with kings and priests, creates ‘nets of religion’. With these nets (on which he is resting his elbows in this picture), he keeps the people down. He uses them to restrain their yearning for freedom and justice (as in The Chimney Sweeper) and to suppress their sexual desire (as in The Garden of Love). Urizen is therefore in conflict with Orc, the revolutionary spirit.