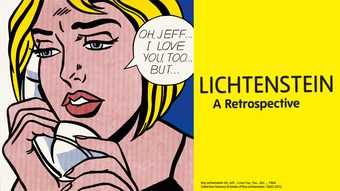

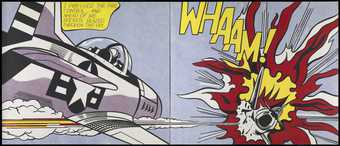

Roy Lichtenstein is known for his works based on comic strips and advertising imagery, coloured with his signature hand-painted Ben-Day dots (the tiny printed dots that appear in print processes). This film brings together archival footage of Lichtenstein at home and at work in his studio, as well as interviews with his wife Dorothy and friend Frederic Tuten to create an intimate portrait of the artist.

A retrospective exhibition of Lichtenstein’s work, including 124 of the artist’s most definitive works was shown at Tate Modern in 2013.

A 'diagram' is maybe a good word for the way I represent other artists. That may be true of cartooning, that it tends to be a diagram of a person. It seems to depict by outlining and delineating in a simple way what a subject is.

The studio was his favourite place. It was the idea that he could actually come down and play. Sometimes he just liked to come down and even clean his paint brushes and look around at the work he was doing, you know, at that time.

He worked at a pretty regular schedule. I mean, he was usually in the studio by ten, had the same thing for breakfast every single morning. Broke for lunch. Came back and worked.

It wasn’t like, I have to go to work today, God, I have to paint today, nothing. It was his joy, it was his pleasure, it was everything. Sometimes I’d go to the studio in Southampton and he’d be alone in the studio. I’d sit in this little chair and watch him work. But I thought I’d be distracting him. No, I’d watch him work and he was just focused. Nothing could distract him.

He never really dreamed that he would be able to support himself through just painting. That was something that made him truly happy.

So the question of the hour is, how are you going to work in Rome?

I am going to do some drawing and thinking and mostly eating, I think.

He was exactly, the first day I met him to the day I never saw him again, the same way. Easy going, charming. He wasn’t judgemental.

I was working at the Bianchini Gallery in New York and we did an exhibition called the Great American Supermarket. And thought, wouldn’t it be great if instead of a regular poster we could get Roy Lichtenstein and Andrew Warhol to put an image on a shopping bag. They both agreed, and I met Roy in 1964 when he came in to sign the shopping bags.

Well it was ’64, so he was pretty well known. He was an internationally known artist. There was still great controversy. It was in the air. Was pop art serious? Is it this? Is it art? All that stuff was still up there. A lot of people were upset about it, you know, and abstracted impressionist must have felt pretty upset, because they saw their whole anguish to the world vanish in this kind of ironic and witty and beautifully done work.

What I did in these early paintings was frightening to me really, in that it seemed to go counter to a sense of taste that I developed along with my hopeless sense of art. Except I knew it had meaning and I knew, very shortly, that it had more meaning than the things I had done before. But, because it was so different it was really frightening.

He was not a fan of comics. It was the nature of the cartoon. It just seemed as far away from an artistic image as you can get, and to try to transform that into a formal painting really appealed to him.

He also found it impossible to go back to doing what he had been doing. I must say, he never quite managed to get the tormented look in those paintings. He wasn’t the tortured artist. He used to joke and say he was going to take curmudgeon lessons.

When Roy was at Ohio State, he had an art professor, Hoyt Sherman, who was a huge influence on him. Talked all about ways of seeing and perception. He had methods of teaching where he flashed slides in a dark room really quickly and had people sketch them, so that they could get kind of Holmes or [Gestalt 0:05:26] of the work. That really had a major impact on Roy.

When I turn the work upside down, it’s to obliterate the subject, or to re-sense it. Think of it more as pure mark and then you can subject. You can see it clearly if you look at it through a mirror because it reverses everything. And anything you don’t want is sort of doubly off because it’s the other way around. It’s almost the same as coming back two weeks later or something and looking at it. And then you see what’s off then.

Art’s about something that’s entirely different from what my original sources were. And I liked the contradiction. I think people mistake the character of line for the character of art. But it’s really the position of the line that’s important, or the position of anything, any contrast. Not the character of it.

Anything that was kind of high flung always amused him and he himself had just kind of natural humility really.

I paint the pictures and he sells them as that. What could be better? Uh-huh, it’s pretty simple. Leo.

Well I’ll try to be a little bit more complicated, but not too much. And I would say that there are several kinds of relationships that can exist between and a dealer and a painter. The best one is the one that, one of friendship. And that’s what my relationship is to Lichtenstein.

Well that’s true.

Leo Castelli was his dealer for his entire life from 1961 until his death, and they trusted each other completely. They never had a contract.

As Roy started to become kind of more successful and better known, he used to joke and say, someone’s going to be tapping him, Mr. Lichtenstein, it’s time for your pills. And he would be in a wheel chair and, with his hat cocked on his head, and he would still be living in Oswego in New York, snowed in and, this would all have been a dream.