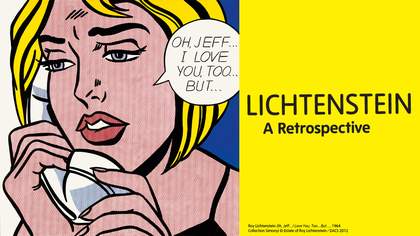

America is often seen as the home of Pop Art, but many European artists were producing ground-breaking work, some of which made reference to Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings.

Richard Hamilton once described Roy Lichtenstein as the most ‘marvellously extreme’ of American Pop artists. More than anything else it was the purity of Lichtenstein’s art that impressed Hamilton, the remarkable way in which his comicbook paintings were ‘true to the mass media’. Just as one might commend George Stubbs for his faithful representations of animal anatomy, or Claude Monet for accurately recording the impression of light on the retina, so Lichtenstein’s paintings provided a true picture of contemporary US culture, and indeed were integral to it — not a picture of that world, but the world itself.

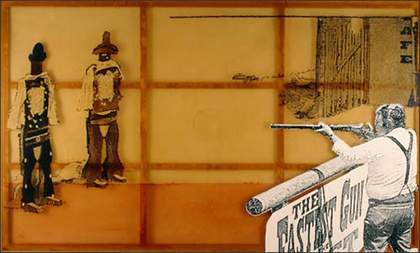

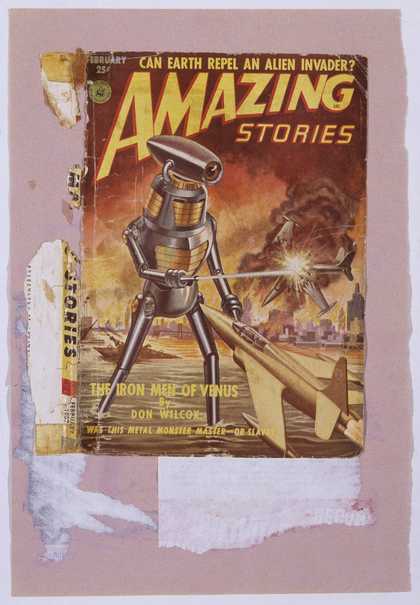

Pop Art in America was, according to this view, the real thing. Outside of the US, it was condemned to being a second-hand reflection on the American way of life. Even those British artists who had pioneered research into popular culture in the early 1950s held the Pop sources of comic books, advertising and food packaging at arm’s length. The images they produced seemed less a matter of enthusiasm for consumer society than a reflection of the state of post-war Europe. Just look at the worn and torn state of Paolozzi’s famous pioneering Pop collages from the Bunk! series (made from around 1947 to 1952). Pop Art avant la lettre, to be sure, but bearing the scars of the past rather than the hopes for the future.

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi

Was This Metal Monster Master - or Slave? (1952)

Tate

Even when Pop emerged with some force at the 1956 exhibition This is Tomorrow, it was still a matter of sociological analysis rather than creating works of art. Among the collaborations at this show, the one that stood out, by Hamilton, John McHale and the architect John Voelcker, featured dazzling wallpaper, a cinema poster cutout and a juke box. Yet the Pop Art element seems in retrospect almost accidental. Hamilton’s famous collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? 1956, now a standard cover image for books about Pop Art, was made as an illustration for the poster of the exhibition, and only shown (and sold) as a work of art a number of years later.

When the second generation of British Pop artists emerged in 1964 from the Royal College of Art – David Hockney, Derek Boshier, Pauline Boty, Allen Jones and Peter Phillips – the stage had been set and Pop Art established. Yet by now the lines of demarcation had also been drawn, with a strong sense of the distinction between American and European practice. For British critics, at least, it was an entirely Anglo-American affair. John Russell (one of the greatest of post-war British art critics) described the ‘special relationship’ in the arts between the UK and the USA; some compensation for the failure of this relationship in politics. Yet, like Hamilton, Russell also saw it as an imbalanced affair – if British Pop was about ‘the thing chosen, as an act of intelligence’, for Americans it was the ‘thing lived’. Lichtenstein’s effortless conjugations of traditional painting and mass culture were the basis of a ‘natural’ art, and as such would always be superior to paler reflections from further afield.

Seen from a purist perspective, this view still holds true today. The great achievements of Lichtenstein, Warhol and artists such as Ed Ruscha arise from an intimate interrogation of mass culture, which seemed to come from nowhere and influence everybody. Yet in recent years a broader, more international view of Pop Art has emerged, of transatlantic connections and regional variations, particularly in Western Europe, where artists from Reykjavík to Madrid have sought to engage with a world of advertising and consumerism, fashioning Pop Art in their own image, more or less in contestation with America.

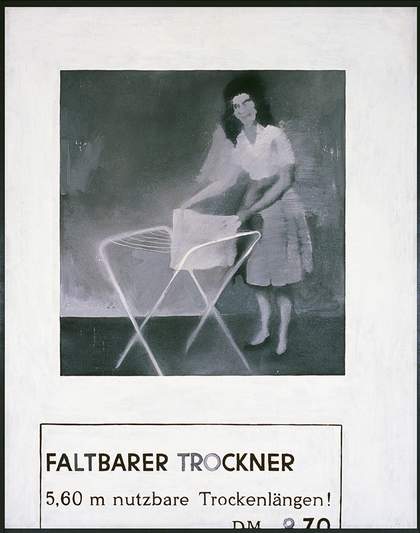

Gerhard Richter

Folding Dryer 1962

Oil on canvas

99.3 x 78.6 cm

For many of these artists Lichtenstein remained the touchstone. Gerhard Richter recalled that the first Pop Art he encountered was a reproduction of Lichtenstein’s Kitchen Stove 1961–2, which made a deep impression on him, ‘because it was anti-painterly. It was directed against “peinture”.’ In one simple gesture it dismissed all the burdensome elements of tradition – expression, style, meaning – which for Richter’s generation were in need of dismissal or renewal. His painting Folding Dryer 1962 is based on a newspaper advertisement for a folding clothes dryer, and is one of a number of images he directly transcribed from printed sources, emphasising the everyday quality of the subject matter. Like Lichtenstein and Warhol, he underlines the pathos of consumerism, the flimsy banality of advertising and the desires that it provokes. Richter was one of a group of German artists who combined the spirit of Pop Art with a satirical and critical attitude to the aftermath of the war, and in particular the Wirtschafstwunder of West Germany and its social market economy. They had been born in the East, then moved West, and thus were able to see both economic systems from the perspective of the other. Richter’s friend Sigmar Polke had been born in Lower Silesia, but moved to the West in the early 1950s. His 1964/5 painting Freundinnen (Girl Friends) shows a clichéd image of happiness filtered through the media – in this case represented by the way in which the photograph has been ‘screened’ for printing, a process of ‘rasterisation’ that fascinated Polke. Although the filtering may remind one of Lichtenstein’s use of Benday dots to make the image more immediate and unambiguous, Polke utilised it to push the subject away, creating a sense of veiling and anonymity.

Sigmar Polke

Freundinnen (Friends) 1965–6

Oil on canvas

99.3 x 78.6 cm

Pop Art in France was by contrast more a matter of direct protest than satire. It was implicated, at least at first, in a larger movement known as Nouveau Réalisme. The label was imposed in 1960 by the critic Pierre Restany to the almost immediate distaste of the artists to whom it referred, and who spent the rest of their careers trying to shake off both Restany and the label (a process that acquired its own term, dérestanysation).

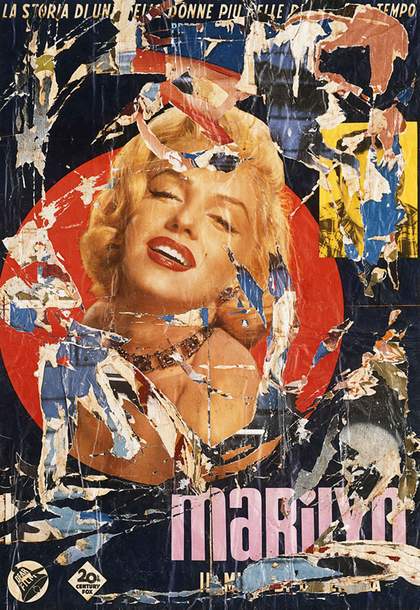

Where Pop was about a new world of consumer optimism, synthetic colours and glamorous commercialism, Nouveau Réalisme implied an older world of entropy and ruin, of things falling apart – what was referred to at the time as a Pompéi mental: ruins of the mind. The two sensibilities came together most strikingly in the affiches lacérées, or torn posters, created by a number of artists, above all Mimmo Rotella (an Italian living in Paris), whose Marilyn of 1963 sums up this conflict between the old and new worlds. Other notable ‘rippers’ include Jacques Villeglé and the German artist Wolf Vostell, both of whom would raid advertising hoardings for the palimpsest-like encrustations of posters torn to create stark, surrealistic juxtapositions, revealing quite literally the underside of consumer dreams.

Mimmo Rotella

Marilyn Monroe 1963

Collage

140 x 100 cm

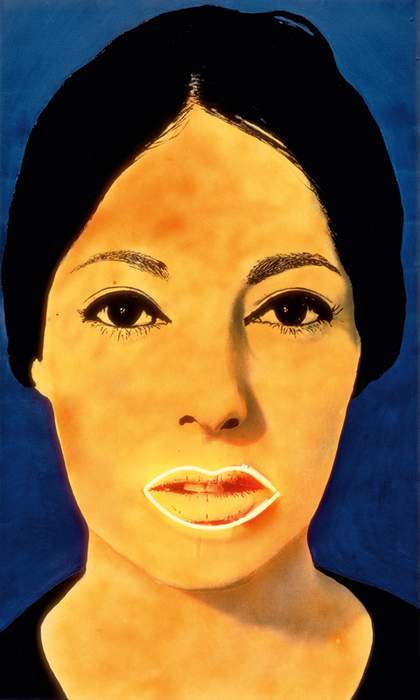

One of the leading lights of French Pop Art, Martial Raysse, was similarly drawn to showing the shabbier fringes of consumerism. In the early 1960s he created assemblages using cheap plastic toys, a thin, ersatz aesthetic accompanied in the case of his installation Raysse Beach, a stage-set made for an exhibition in Amsterdam in 1962, by the sound of pre-Beatles rock ’n’ roll. Later he became more critical of the celebrity image world of American Pop Art, a position given forceful expression in 1965’s Peinture à haute tension (Painting at high tension), featuring an anonymous female face with neon lips. The eroticism of Pop Art is switched around with abrasive intellect – you can kiss a Lichtenstein, it seems to say, but you can’t kiss me.

Martial Raysse

High Voltage 1965

Oil and fluorescent paint on canvas

162.5 x 97. 5cm

The Pop Art of Raysse and other French artists including Raymond Hains, Alain Jacquet, Gérard Deschamps, Niki de Saint Phalle and César was more or less steeped in a politics of protest. America was to be criticised both as the epitome of irresponsible consumption, and also as the source of military aggression in Vietnam. French artists aimed to rival American Pop Art, but also to undermine it. In the early 1960s Deschamps, an intriguing and somewhat neglected artist, made large painterly reliefs from signalling tarpaulins used by the American army, and also from sheets of iridescent metal from abandoned, or perhaps crashed jet engines. He later turned to a more Pop idiom, and with the 1965 painting Trois Lichtenstein = Un Deschamps threw down the gauntlet on behalf of French painting in general to the New York artists who by that time had achieved international fame. Jacquet’s Camouflage Lichtenstein ‘The Kiss’ 1963 transforms Lichtenstein’s Benday dots into something more sinister and martial. French Pop was all about the tensions and threat on the peripheries of consumerism, and about turning Pop Art and pop culture against itself.

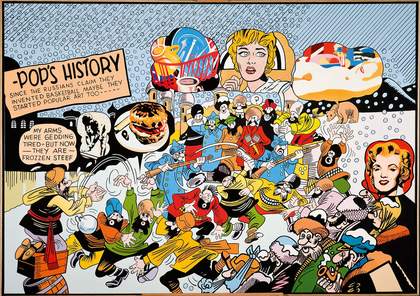

Erro

Pop’s History 1967

Glycerophtalic paint on canvas

115 x 170 cm

The Vietnam war was for many European artists the turning point in their relationship with American culture. Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Vietnam 1965 and Wolf Vostell’s B52 1968 are eloquent in taking the visual look of American Pop and turning it against the culture from which it sprung, in the spirit of outright protest. How effective this was is an open question. It is easier to celebrate and satirise than to campaign for change. The effect on the spirit of Pop Art was at least to question the ‘purity’ of the American version, and the subaltern relationship of European artists. The Icelandic artist Erró (born 1932) adapted his earlier classical training as a painter and mosaicist to consumer imagery after visiting the US in the early 1960s. His 1967 painting Pop’s History includes images taken directly from American Pop artists, including a Lichtenstein painting of a nurse. Armed cartoon Muscovites play a primitive game with a snowball and make the suggestion that as basketball was a Russian invention (the claim is more often made for baseball), then why not Pop Art also?