August Sander The Painter Otto Dix and his Wife Martha 1925-6, printed 1991 © Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London 2017

1. August Sander didn’t come from an artistic background

August Sander’s father was a mine carpenter and, later, the family ran a small plot of farmland. Sander first discovered photography at the local mine, while helping carry the equipment of a company photographer. His son Gunther said, that looking through a camera ‘transfixed him – and not just for that instant’. He spent his military service (1897–99) as a photographer's assistant and went on to set up his own photography studio in Cologne in 1909.

2. One of his projects lasted his whole career

August Sander Farmer's Child 1919, printed 1990 © Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London 2017

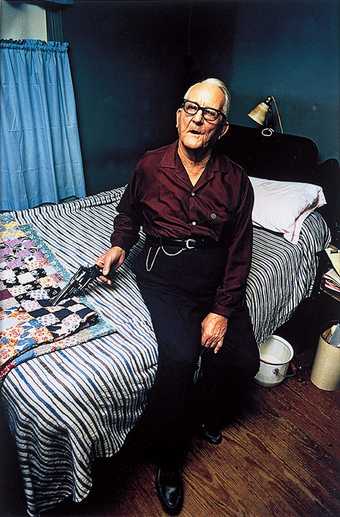

In the mid-1920s, Sander began his highly ambitious project People of the 20th Century. In it, Sander aimed to document Germany by taking portraits of people from all segments of society. The project adapted and evolved continuously, falling into seven distinct groups: ‘The Farmer’, ‘The Skilled Tradesman’, ‘The Woman’, ‘Classes and Professions’, ‘The Artists’, ‘The City’ and ‘The Last People’.

Sander once said ‘The portrait is your mirror. It’s you’. He believed that, through photography, he could reveal the characteristic traits of people. He used these images to tell each person's story; their profession, politics, social situation and background.

3. He captured a key moment in German history

August Sander Working Students 1926, printed 1990 © Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London 2017

Seen together, Sander’s images form a pictorial mosaic of inter-war Germany. Rapid social change and newfound freedom were accompanied by financial insecurity and social and political unrest. By photographing the citizens of the Weimar Republic – from the artistic, bohemian elite to the Nazis and those they persecuted – Sander’s photographs tell of an uncertain cultural landscape. It is a world characterized by explosions of creativity, hyperinflation and political turmoil. The faces of those he photographed show traces of this collective historical experience.

Alfred Döblin, author of the 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz said:

Sander has succeeded in writing sociology not by writing, but by producing photographs – photographs of faces and not mere costumes.

4. Sander avoided new technologies

August Sander National Socialist, Head of Department of Culture c.1938, printed 1990 © Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London 2017

Sander did not use the newly invented Leica camera. Instead he remained devoted to an old-fashioned large-format camera, glass negatives and long exposure times. This allowed him to capture minute details of individual faces. Sander prized the daguerreotype, a photographic process introduced in the previous century, of which he said: ‘it cannot be surpassed in the delicacy of the delineation, it is objectivity in the best sense of the word’. Allied to this, his portraits were anonymous. Shot against neutral backgrounds and titled more often than not by profession alone, he let the images – and the faces in them – speak for themselves.

5. His influence cannot be overestimated

![August Sander Photographer [August Sander] 1925, printed 1990 © Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London 2017](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/august_sander_august_sander_1925_printed_1990_.width-340_FLDWI7A.jpg)

August Sander Photographer [August Sander] 1925, printed 1990 © Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London 2017

The ambition and reach of People of the 20th Century (both in terms of the quality of his photography and in his representation of a cross-section of society) made him a monumental figure of twentieth century photography. The likes of American social realist photographers such as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange (whose works became iconic symbols of the depression), and later photographers such as Diane Arbus, each owe a debt to the trailblazing Sander. More recently, the work of conceptual artists such as Bernd and Hilla Becher (known for their typologies of industrial buildings and structures) and Rineke Dijkstra, whose photography is infused with psychological depth and social awareness, resonates with the influence of August Sander’s career-long project.

Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919–1933 is on at Tate Liverpool 23 June – 15 October 2017