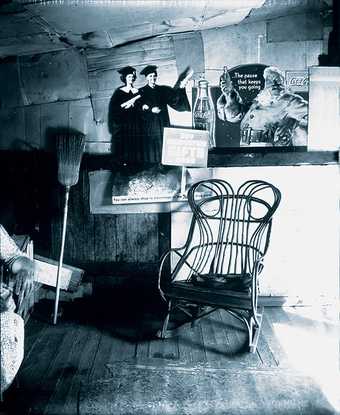

In 1932, Walker Evans photographed a young couple in a roadster parked at the curb in a small town somewhere in America. The top is down, giving the photographer and his subjects direct views of one another. Gazing back at the lens, the young man seems bemused in a block-headed way. On the evidence of her vigorous squint, the young woman is extremely peeved. At first glance – which is all that the photograph can give us – it seems obvious that, of the two, she is the driving force. He, with his hands resting calmly on the steering wheel, just drives. Yet we can’t be sure of any of this. We can’t even be confident that Evans has pictured a couple. Perhaps the woman isn’t peeved so much as fearful. Who is this stranger with a camera? Why is he taking our picture?

Evans doesn’t just show us people and things at a particular instant. He persuades us to see how irretrievably that instant has passed, to be succeeded by others, uncountable and – more to the point – unaccountable. Rather than freeze time and deliver us a neatly wrapped package of certainties, Evans’s photographs deftly fling us into an abyss where everything is up for grabs. As Evans wrote in 1931, ‘The element of time entering into photography provides a departure for as much speculation as an observer cares to make.’ So his best pictures count as works of art not because they make matters clear. They count as art because, in spite of their accuracy, they do nothing of the kind. They call their subjects into question and leave us with the task of coming up with answers.

Still, his comment about ‘time entering into photography’ might sound a bit odd. Surely the mechanics of the lens and the chemistry of the developing tray endow every photograph with a temporal air. Strictly speaking, they do, but when Evans spoke of time there were still devotees of the idea that ‘art-photography’ imitates the ‘timelessness’ of painting. Photographers would dress their models in costumes modelled on the clothes in Old Master pictures. Impressionism was also imitated. Evans could abide none of it. Dismissing the trappings of ‘art-photography’, he proceeded on the assumption that photography could be an art on its own terms. Others agreed, among them Berenice Abbott and Dorothea Lange.

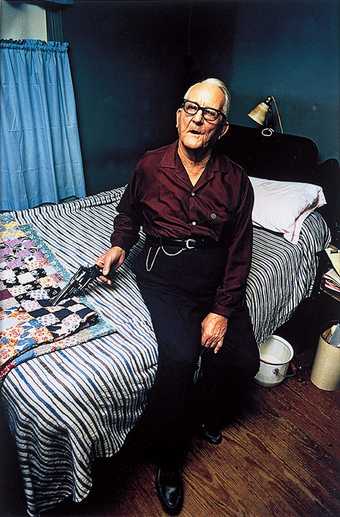

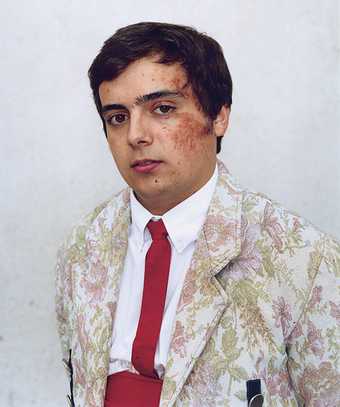

The tradition launched by Evans, Abbott, and others has persisted to the present. Major postwar practitioners include Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus, who began as a fashion photographer. After studying with the documentarian Lisette Model in the 1950s, she turned to the ordinary world and found extraordinary subjects: nudists, transvestites, inmates of psychiatric facilities, residents of homes for the elderly, young families with children. Usually, she showed these people engaged in routine activities: a transvestite curling his hair; inmates taking a walk; a pair of senior citizens, in crowns and robes, posing as king and queen of the dance. We expect to see a certain distance between social or sexual categories and the people who fill them. What makes Arbus’s pictures so affecting – even terrifying, on occasion – is the sheer badness of the fit. Some of her people have chosen their roles, others play parts chosen for them. All seem to be utterly lost in ways of life that provide them neither a full measure of humanity nor the means of escape.

Detractors accused Arbus of seeking out people to mock. Her defence was the documentarian’s: I only photograph what is there. Yet the pictures she chose to show are never of merely documentary interest. With her untiring eye for the anguish of unresolved selves, Arbus formulated a brief against the very nature of society. The roles it permits us, like the categories to which it assigns us, are supposed to integrate us into a communal unity. But, given our incorrigible differences, how can those roles be anything but alienating burdens? To fret about individuality may, of course, be no more than a quirk of American behaviour. In another place at another time – Germany early in the 20th century – August Sander quietly celebrated social roles in all their confining clarity.

Roaming his own country with the eye of an anthropologist, Sander sought types, not individuals. The petit bourgeoisie, the grand bourgeoisie, peasants rich and poor, the proletariat, literati, bohemians – all these and more appear in Sander’s photographic inventory. With their rigid postures and direct gazes, his subjects seem content, if not happy, to be seen as representatives of social categories. For all its regulatory power, however, Sander’s documentary format could not reduce everyone to an exemplary instance of a generality.

Walker Evans’s best pictures count as works of art because, in spite of their astonishing accuracy, they call their subjects into question and leave us with the task of coming up with answers.

Young Farmers 1914 shows three rural gents in their Sunday best. Not one of them appears to chafe against his lot in life. Yet this picture is laden with signs that each of these young men inhabits his role with a difference. Individuals, not just types, they prompt ‘as much speculation as an observer cares to make’ – to borrow Walker Evans’s phrase. Sander’s Girl in a Circus Trailer 1932 challenges us even more imperatively, for this is a thoroughly enigmatic image. It is not that one can’t imagine what she is thinking. Rather, there is no end to speculating about her thoughts and feelings. The ambiguities of this image offer us nothing but uncertainties and a reminder of the need to make sense of the briefest instant, the most tenuous contingency. Because, as every great photograph subtly goads us into realizing, contingencies are all we have.

Sander’s oeuvre is vast and mostly unfamiliar. Of all his images, only Young Farmers, Girl in a Circus Trailer and two or three others have become familiar, for only these can sustain the claim that Sander is an artist. The rest are documents. In making these distinctions, it helps to remember that photography was invented, in the late 1830s, as a mechanical means to record information that, until then, could be gathered only by hand. The camera replaced the topographical draughtsman, the botanical illustrator and any number of patiently anonymous image-makers.

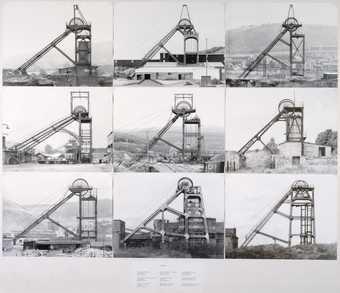

Like documentary photography, video can satisfy our legitimate interest in the look of people and events, past and present. But there is no need to call a document a work of art, nor would there be any need to make this obvious point if art galleries and museums had not been crowded in recent years by photographic images which have little beyond their documentary value to recommend them. We are living through a protracted epidemic of confusion about the difference between artworks and documents. A border is being blurred, and to understand why we need to take a second look at August Sander and other borderline cases. Sander’s purpose was investigative, and he achieved it. His oeuvre could be seen as a warehouse of information about German social types. Of course, even his most impersonal images betray a point of view, a set of assumptions and idiosyncrasies of style. So do other forms of non-fiction: medical examiners’ reports, memoirs with no literary pretensions, photographs taken at crime scenes. Only a few of Sander’s images send us down speculative paths of the kind that lead some to conclude that he was an artist – or could be, now and then. Sander was an artist inadvertently. So are Bernd and Hilla Becher, though the inadvertency that made them into artists is rather different.

In the wake of the Second World War, German photography was strongly influenced by Henri Cartier-Bresson and his aesthetic of ‘the decisive moment’ – that instant in the familiar flow of life when something unfamiliar is suddenly glimpsed. Cartier-Bresson’s style was anecdotal, even Chekovian, and the Bechers wanted no part of it. Striving for absolute objectivity, they set about improving on Sander’s anthropological method. The first step was to get rid of people, whose personalities sometimes broke through the constraints of type. For types of people the Bechers substituted types of things: houses, water towers, blast furnaces, grain elevators and so on. Each instance of a type is photographed straight on, from precisely the same angle, and the results appear in gridded arrays: three rows of three houses, four rows of four oil refineries.

The Bechers formulated this austerely documentary style in the late 1950s. By the mid-1960s it had caught the eye of Carl Andre and other American Minimalists. For most of its history, Western art shied away from the literal; the Minimalists made it the premise of their art. ‘What you see is what you see,’ said Frank Stella, who had made his mark by covering large canvases with symmetrical patterns of black stripes. When you weren’t seeing Stella’s black stripes, you could see Robert Morris’s grey cubes or Sol LeWitt’s white grids. The objectivity of the documentary photographer began to look like the literalism of the hottest new style. The Bechers fitted right in.

By the end of the 1960s, certain younger artists were looking for ways past the Minimalists’ stripes, cubes and grids. Though they had no quarrel with literalism, they were no longer willing to let the plain white cube of gallery space contain their art. Breaking out, Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer built immense earthworks in the desert. In non-art sites around New York, Vito Acconci and Dennis Oppenheim presented what came to be known as performance pieces. Few saw them, or travelled to Utah or Nevada to look at earthworks. Inaccessible or ephemeral, this new art was known chiefly through photographic documents – often just scruffy, black-and-white snapshots, but acceptable nonetheless. The convergence of Minimalism and the Bechers had given documentary images a secure place in the world of art.

We are living through a protracted epidemic of confusion about the difference between artworks and documents. A border is being blurred.

Smithson, Heizer and the rest made it clear that, despite their reliance on photographs, they were not photographers. Wherever their art might be – in a faraway desert or in a sequence of actions performed once and never repeated – it was not to be found in their snapshots. Nonetheless, slippage occurred. By the end of the 1970s, documents were being taken for works of art. To point to this confusion is not to deny that documentary photography has its virtues. And the Bechers, in particular, have been up to something of real interest during the past four decades.

Recording and arranging their subjects with unflagging care, they make a visual argument for essences: Platonic forms of which particulars are only instances. Things have no value in themselves, only in relation to the ideal. Our Platonic impulses are persistent. But, fascinating as it is to watch our yearning for the absolute reach into the realm of documentary photography, this is just what we don’t need. The Bechers define us the wrong way, as observers who can somehow step out of time – and the limits of individuality – for a glimpse into the essential nature of things.

With the help of the Bechers and the heirs of Minimalism, photography – the marginal medium – had marginalised painting. Then, in the 1980s, painting made a spectacular comeback. At the hands of Anselm Kiefer, say, or Julian Schnabel, paintings themselves took on the scale and the aura of spectacle. Photographers fought back with big, lusciously produced colour prints. During the past decade, none have been bigger or more gorgeously chromatic than the photographs produced by a trio of the Bechers’ students: Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth and Thomas Ruff.

The Bechers never abandoned the no-nonsense clarity of the medium-sized black-and-white print. From American photographers of the 1970s – notably Stephen Shore and William Eggleston – Gursky, Ruff and company learned the allure of lush colour and large prints. Of this group, Gursky is the slickest. He gives his images of milling crowds and geometric architecture a bland and seamless unity they couldn’t possibly have in real life. A Platonic documentarian, Gursky offers us a God’s-eye view – or the look of it – and nothing good can come of that. There are no timelessly true revelations on genuine offer, in the art world or anywhere else. To hang on to our humanity, we must remain aware of our immersion in time and happenstance. Gursky would like his frozen images to lift us up and out of all that.

Early on, Struth had a similar ambition. His early photographs might be called Becher variations: black-and-white shots of anonymous building types in a style as anonymous as he could make it. Next came equally detached views of city streets. Black and white gave way to colour, yet the flat effect of Becher-style documentary persisted. Then something remarkable happened. Struth embarked on a Grand Tour, from one cultural landmark to the next. Photographing the tourist-filled interiors of museums and cathedrals, he sometimes recalled the light side of photojournalism – a Life magazine feature, perhaps, on the fun of foreign travel. Occasionally, he produced allegories of the relation between art and life. At the Louvre, Struth took of a picture of Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa. On the raft, starving bodies strain into poses of High-Romantic extremity. In the foreground, the shadowy figures of museum-goers gather into a respectful herd. Showing the human condition as heroic and placid, as the stuff of stirring fiction and dull non-fiction, the best of Struth’s Museum Pictures bring him right to the border that separates artworks from documentary images.

With his recent Paradise series – large, luminous, almost aqueous pictures of jungles – he crosses over. Every detail is in sharp focus, yet the eye feels enfolded in ambiguity. There is no end to the puzzles about space and perception posed by these images. Here, seeing can only be speculative. Thomas Ruff, too, guides vision into a speculative mode, though he began as a proponent of Becherism. He spent the early 1980s recording his friends’ faces in a format that mimics all but the size of the passport photo – like Gursky and Struth, Ruff tends to enlarge the photographic print to the size of a biggish painting. In Ruff’s portraits, faces are as expressionless as their owners can make them. Having treated human features as the Bechers treated water towers and blast furnaces, Ruff made his own architectural series: in place of blank faces, the blank faades of banal postwar office and apartment buildings.

Among his later works are several series of readymade images, including the Newspaper Portraits, which recycle anonymous photographs of generic events: politicians shaking hands, a rocket launch. Stars began with telescopic images of the night sky acquired from an observatory. Enlarging and digitally altering these black-and-white patterns, Ruff pushed documentary photography to the verge of abstraction. Next came Night, a suite of prosaic – and of course nocturnal – vignettes of suburban Düsseldorf, Ruff’s native city. Parked cars and doorways appear in a greenish glow reminiscent of television coverage of the 1991 Gulf War, which introduced the light-amplifying technology Ruff used to make these pictures: the triteness of peace in the weird light of war.

Working without a camera in the past few years, Ruff downloads porn images from the internet. Then, using a computer, he gives them a soft, blurry focus. The relentlessly explicit becomes elusive. Pornography’s repertory is limited, so there is no real difficulty in deciphering these images. Ruff’s lush ambiguities hide nothing. Instead, they release the viewer from the supposed necessities – the seemingly incontrovertible truths – of documentary photography. Thus liberated, you are left where art always leaves you: on your own, to make of the image whatever you can, given who you are and what you desire. Of course, these givens are not always known. Trying to make sense of an artist’s work, we sometimes reveal – even revise – ourselves That is why we need art.

There is no need to call a document a work of art, nor would there be any need to make this obvious point if art galleries and museums had not been crowded in recent years by photographic images which have little beyond their documentary value to recommend them.

But we also need information, the less prettified the better. Of all the documentary photographers presently at work, Boris Mikhailov may be the least Platonic. Every homeless person he pictures is sunk in a misery so solitary that even sexual contact can’t relieve it, only show up its intractability. Working on the border of art, Mikhailov sometimes makes pictures equal to Sander’s Circus Girl or the best of Walker Evans. On other occasions, he just registers a cipher of inaccessible wretchedness. Each of his images has to be judged on its own hair-raising merits – and that is never easy, in part because Mikhailov has such a sure eye for troubling subjects. Moreover, it can be difficult simply to see what the subject is. Even the most straightforward document can baffle the eye.

Wassily Kandinsky and other Modernist mystics claimed that images transmit their meanings directly to the mind or spirit. This is nonsense. Meaning is generated in the course of an interpretive embrace, and images of different kinds demand different styles of interpretation. We bring one set of norms into play for a proper look at meteorological chart, another for a family snapshot, and so on. But, you might object, aren’t there moments when a particularly keen and inventive eye sees data in a new way? And don’t those moments bring something like an artist’s inventiveness to bear on documentary images? Maybe, though, the point of such creativity is to institute a new set of norms, a new interpretive routine.

The point of art of is to keep us from settling into routines of any sort. Never letting me feel certain that I have found the right way to look at it, an artist’s image puts everything in doubt – not just its own meaning but mine, for a work doesn’t count as an artwork unless its ambiguities, uncertainties and obscurities throw me back on my own resources. Allowing me no appeal to a standard way of looking, a work of art forces me to declare my interests and values and attitudes – in short, myself – and grapple with the work until I have made my own sense of it. A document of any sort casts the viewer as a passive receiver of information, and no doubt there are times when it makes sense to be no more than that. But art is better. Turning seeing into speculation, art brings us alive to ourselves and to the world. Information just helps us function.