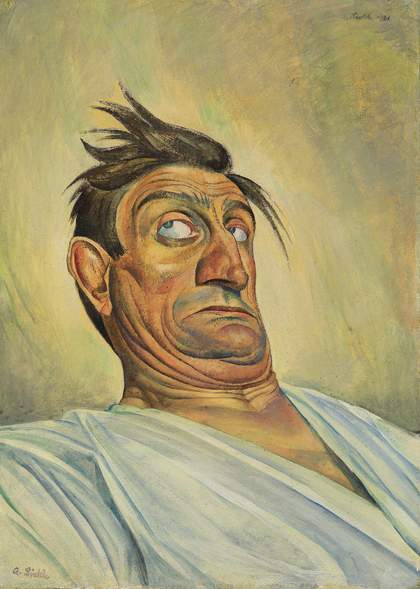

1. He was a portraitist

Otto Dix Portrait of the Photographer Hugo Erfurth with Dog 1926 © DACS 2017. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

German artist Otto Dix was a committed painter of portraits. At a time when photography had diminished portraiture’s importance and the genre was seen as a deeply unfashionable pursuit for so-called serious artists, he was making a living – and cementing his reputation – out of exactly that. He commented:

Painting portraits is regarded by modernist artists as a lower artistic occupation; and yet it is one of the most exciting and difficult tasks for a painter.

2. He fought in the First World War

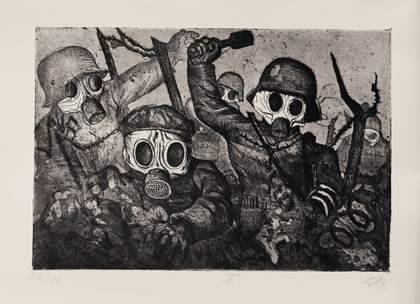

Otto Dix Assault Troops Advance under Gas (Sturmtruppe geht unter Gas vor) 1924 © DACS 2017. Image: Otto Dix Stiftung

Dix served in the First World War from 1915, fighting on the Western front in the Battle of the Somme. Although an enthusiastic soldier – his service earned him the Iron Cross (Second Class) – Dix’s experiences affected him deeply. He marked the war’s 10th anniversary with a group of etchings entitled Der Krieg (The War), leaving few of the horrors of the front line to the imagination. Commenting later, he said:

For years, [I] constantly had these dreams in which I was forced to crawl through destroyed buildings, through corridors through which I couldn’t pass. The rubble was always there in my dreams.

3. Dix took inspiration from the Old Masters

Otto Dix Self-Portrait with Easel 1926 © DACS 2017. Leopold-Hoesch-Museum & Papiermuseum Düren. Photo: Peter Hinschläger

From the early 1920s, he devoted himself to the study of old master painting techniques, using a layering effect, produced first with egg tempera and, later, finished with oils. This moved his contemporary George Grosz to jokingly call him ‘Otto Hans Baldung Dix’ (after the German old master Hans Baldung Grien). Later, Grosz would write:

Dix did all the drawing in a thin tempera, then went over it with thin mastic glazes in various cold and warm tones. He was the only Old Master I ever watched using this technique.

4. He painted what he called ‘life undiluted’

Otto Dix Reclining Woman on a Leopard Skin 1927 © DACS 2017. Collection of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University. Gift of Samuel A. Berger; 55.031.

Dix was a key supporter of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement, a name coined after an exhibition held in Mannheim, Germany in 1925. Described by art historian G.F. Hartlaub, as ‘new realism bearing a socialist flavour’, the movement sought to depict the social and political realities of the Weimar Republic. Speaking in 1965, Dix said:

We want to see things completely naked, clear, almost without art. I invented the New Objectivity.

5. Dix and the Nazis

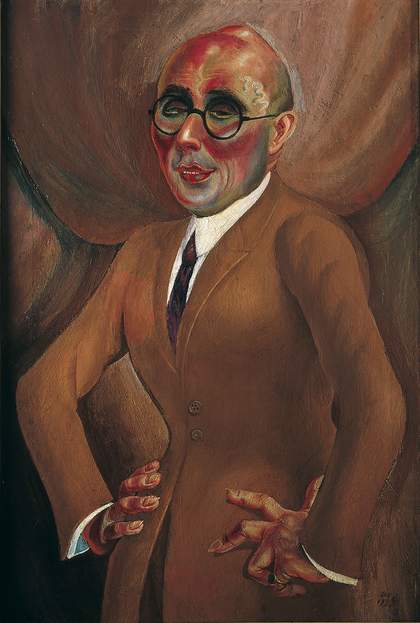

Otto Dix Portrait of the Jeweller Karl Krall 1923 Kunst- und Museumsverein im Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal / Photo: Antje Zeis-Loi, Medienzentrum Wuppertal. © DACS 2017.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Dix was dismissed from his professorship teaching art at the Dresden Academy, where he had worked since 1927. The reason given was that, through his painting, he had committed a ‘violation of the moral sensibilities and subversion of the militant spirit of the German people’.

In the years following, some 260 of his works were confiscated by the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. Several of these works, including The Jeweller Karl Krall 1923 (which features in the Tate Liverpool exhibition Portraying a Nation), appeared in the Entartete Kunst (degenerate art) exhibition of 1937–8. The exhibition was staged by the Nazis to destroy the careers of those artists they considered mentally ill, inappropriate or unpatriotic.

Magic Realism is on at Tate Modern 30 July 2018 – 14 July 2019

![August Sander, Bohemians [Willi Bongard, Gottfried Brockmann] 1922-5, printed 1990](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/august_sander_bohemians_willi_bongard_gottfrie.width-420_zKUox9s.jpg)