Introduction

A Year in Art: Australia 1992 brings together works by Australian artists to examine debates around land rights and the ongoing legacies of colonialism.

In 1992 the High Court of Australia delivered a landmark ruling known as the ‘Mabo decision’. It overturned ‘terra nullius’, a Latin expression meaning ‘land belonging to nobody’. This doctrine had stated that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples did not own the territory they occupied for many thousands of years. The British used this principle to justify taking over the land now known as Australia in 1770.

This exhibition features artworks made before and after 1992 that explore the continuing relationship that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have with their lands. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples do not state that the land ‘belongs’ to them in a Western sense of ownership. The land is not seen as something to be purchased or divided, but rather a living entity that is the basis for and sustains cultural existence. This includes language, lore, family and identity. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a reciprocal, custodial relationship with Country, with the knowledge and responsibility to care for their lands. This is referred to as connection to Country.

Emily Kame Kngwarray’s works exemplify the connection to Country contemporary artists continue to have. Kngwarreye was an Anmatyerre Elder in Alhalkere country, Northern Territory. Her works are based on body painting designs used in awelye (Anmatyerre women’s ceremonies). They represent her knowledge of Alhalkere country as a complex, multi-layered ecosystem integrated with Anmatyerre Creation Stories.

It is an expression of her continued relationship to the land as an Elder and custodian.

This and many of these works in the exhibition reflect on the ongoing impact of colonisation, the complexities of representation in Australian society today and questions of social and environmental injustice.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor.

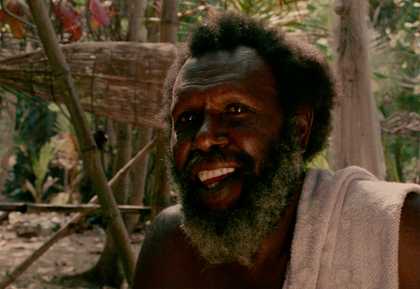

Eddie Koiki Mabo at Las, Mer Island, September 1989, from the film Land Bilong Islanders. Courtesy of Trevor Graham / Yarra Bank Films

Eddie Koiki Mabo and the ‘Mabo decision’

Eddie Koiki Mabo was a Meriam man from the Torres Strait. He was the lead plaintiff of a ten-year legal case in the High Court of Australia to recognise his people’s ownership of Mer Island (also known as Murray Island). The resulting ‘Mabo decision’ in 1992 was a turning point in recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders’ land rights and traditional inheritance systems, also known as native title.

Mabo lived in Queensland, where he was a spokesperson for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In 1974 he learned that the Australian government owned the land he had inherited as part of Meriam custom. In May 1982 he filed a claim in the High Court for native title to portions of Mer Island, along with fellow Mer Islanders David Passi, Sam Passi, James Rice and Celuia Mapo Salee.

On 3 June 1992, five months after Mabo’s death from cancer at the age of 55, the High Court of Australia recognised the claimants’ native title.

3 June is ‘Mabo Day’. It has been celebrated every year in the Torres Straits as an official holiday since 2002. A campaign to make Mabo Day a national holiday across Australia is ongoing.

Ancestral Connections

Yo karreborledmeng mane wanjh bolkki new. Mankerrnge laik, new generation. Bad ngayi ngakarrme bokenh ngakarrme. Mankerrnge la mankare.

The old ways of doing things have changed into the new ways. The new generation does things differently. But me, I have two ways. I am the old and the new.

John Mawurndjul

D Harding

The Leap/Watershed (2017)

Tate

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians practise the world’s oldest continuous living cultures. This room includes artworks by five contemporary artists: Mabel Juli, Nogirra Marawili, John Mawurndjul, Judy Watson, and D Harding. Made since the late 1980s, these highly personal works assert and celebrate the artists’ heritage and their rich connections to Country.

Like Kngwarreye’s paintings in the previous room, Juli, Marawili, and Mawurndjul’s artworks reveal how their roles as Elders of their communities and custodians of their lands are interwoven with their art practices. Ancestral stories are critical in contemporary practice and continued connection to Country. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Country is not just a physical location but an embodiment of history, spiritual beliefs, social ties, ecological concerns and more.

Kngwarreye and Marawili use contemporary materials to depict Country. In Baratjala, for example, Marawili has used material found on the land – in this case, used printer cartridges. It shows how Marawili, a senior artist working in Yirrkala Country, has evolved her practice in response to the changing nature of the landscape.

Mawurndjul, Juli and Harding’s paintings incorporate the land directly, using a clay pigment known in English as ochre. In The Leap/Watershed, Harding blows pigment onto the canvas – a technique that has been used by Aboriginal artists for thousands of years. Mawurndjul incorporates rarrk, a method of fine cross-hatching employed by generations of Kuninjku artists. ‘We don’t paint the actual body, but its power’, Mawurndjul said. ‘We represent its power with cross-hatching, we don’t paint its human form, no. We only paint the spirit, that’s all.’

Watson and Harding’s work addresses the histories of violence experienced by their ancestors and their ongoing legacies, such as frontier massacres and policies of cultural erasure. Mixing techniques and sensual textures, they layer experiences from different eras: ancestral memories, colonial traumas, and recent events such as the economic and psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Peter Kennedy, John Hughes and Yhonnie Scarce

As Australia has begun to re-examine its history, artists have grappled with the legacy of colonial violence, bringing the voices and experiences of generations of First Nations peoples to the fore and denouncing centuries of systematic oppression.

Peter Kennedy and John Hughes made On Sacred Land as the campaign for land rights came to prominence. The video traces the impact of white colonisation and capitalism through found footage and shows Aboriginal peoples’ resistance to the exploitation of sacred sites by mining companies.

In Remember Royalty Yhonnie Scarce addresses the history of her Kokatha family through archive photographs printed onto vintage bed linen and accompanied by handblown glass sculptures. These are gifts to her ancestors, who lived for decades in Koonibba Mission. This was one of many institutions where Aboriginal people were subjected to brutal policies of cultural assimilation and control after being forcibly removed from their Country.

As far as I am concerned my grandparents, great grandparents and those people who walked my Country before me, are Australia’s royalty.

Yhonnie Scarce

How to Cross the Void

If I were to choose a single word to describe my art practice it would be the word question. If I were to choose a single word to describe my underlying drive it would be freedom … To be free we must be able to question the ways our own history defines us.

Gordon Bennett

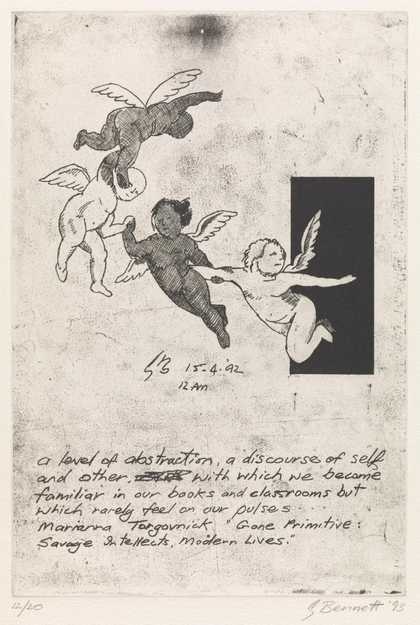

Gordon Bennett

A Level of Abstraction (1993)

Tate

Gordon Bennett based his etchings from the series How to Cross the Void on a visual diary of drawings he created during his artist residency in France between 1991 and 1992. They reveal Bennett’s observations of contemporary Australian culture and his reflections on his experience of ongoing European colonial legacies, particularly racism. Bennett repeatedly uses a black or blue square in the series, which he sometimes refers to as a ‘void’, to question abstraction in modern art and whether it is possible to transcend cultural context.

‘All the works in this series interact on one level or another’, Bennett said. ‘Whether it be the futile effort to escape into the ‘purity’ of Malevich’s square or abstract spiritual world… or the bludgeoning effect of cultural imperialism… or the pain inflicted by such imperialism… or to escape the spirit by suicide… or to find ‘equality’ as an ‘angel’ once one has passed through into the abstract.’

Bennett added handwritten annotations to the visual diary drawings during the etching phase. They reveal the development of the artist’s ideas, providing invaluable insights into his practice. Many are initial sketches or proposals for paintings, sculptures and installations. You can see how Bennett developed and realised these ideas in the painting Possession Island (Abstraction), which is also on display in this exhibition.

Vernon Ah Kee

Vernon Ah Kee

tall man (2010)

Tate

Vernon Ah Kee’s tall man 2010 reveals the ongoing effects of colonisation in contemporary Australia. It depicts events from 26 November 2004, when simmering tensions erupted on Palm Island, an island off the coast of Queensland. A local man, Mulrunji Doomadgee (also known as Cameron Doomadgee), died in police custody as a result of multiple injuries. In the protests that followed, the police station, local courthouse and police barracks were burnt down. Sergeant Chris Hurley, who arrested Doomadgee, was tried and acquitted for causing his death.

One of the central figures leading the protests was Lex Wotton, a member of the Palm Island Aboriginal Council. Ah Kee presents him as the ‘tall man’ – an Aboriginal term for a bogey man or spirit who elicits the truth from wrongdoers. Wotton later won a lawsuit, alongside other Palm Island residents, which found that the police had illegally discriminated against them. The State of Queensland paid them A$30 million compensation.

‘As a people, the Aborigine in Australia exists in a world where our place is always prescribed for us and we are always in jeopardy’, Ah Kee has said. ‘It is a context that we are continually having to survive. It is a context upon which we are continually having to build and re-build.’

Gordon Bennett and Algernon Talmage

Gordon Bennett

Possession Island (Abstraction) (1991)

Tate

I believe in the importance of history in informing one’s sense of identity in the present and in that relationship to shaping one’s perceptions for the future both on an individual level and on a national level since any nation is a collection of individuals.

Gordon Bennett

Colonialism shaped official and popular retellings of Australia’s past. This room brings together two contrasting ways of approaching its foundational myths.

Gordon Bennett based Possession Island (Abstraction) on an engraved copy of a painting depicting Captain Cook claiming Australia for the British crown. By reproducing this image using the ‘dot painting’ style seen in works such as those of the Papunya Tula artists, Bennett encourages audiences to ‘re-read the image, and the mythology’ of colonial history. Bennett also added footprints and a geometric motif in the colours of the Aboriginal flag to cover the inaccurate depiction of a Black figure as a servant in English clothes.

The British artist Algernon Talmage’s The Founding of Australia 1788 is included here as a similar scene to the one that Bennett is questioning. A romanticised imagining of the British raising the Union flag at Sydney Cove, it omits any trace of the violence that followed and of the Eora people on whose land this scene takes place. This painting is typical of the mythology created and replicated in visual representations of Australia’s colonial history.

A window in this room looks out onto St Paul’s Cathedral. Christopher Wren completed the cathedral early in the 18th Century, the same century Captain Cook claimed the east coast of Australia for the British Crown. St Paul’s continues to be an important spiritual site and hosts many State functions, symbolic of British power built at the height of its imperial expansion.

Bonita Ely and Judy Watson

Judy Watson

a preponderance of aboriginal blood (2005)

Tate

This room examines institutional racism in Australia’s official records and the disregard for traditional land rights to allow mining operations.

Judy Watson’s a preponderance of aboriginal blood 2005 reproduces a series of official documents from the Queensland State Archives. As part of the printing process, she overlays blood-like stains, exposing the systemic violence and prejudice that resulted from the laws they represent. Watson describes the ‘stain of history’ on these documents as ‘a cultural pooling of blood that soaks up the past and erupts like a fissure in our psyche'. The archival materials include electoral enrolment statutes that excluded people with a ‘preponderance of Aboriginal blood’ from the right to vote, unless they had a white parent. This official, legal discrimination against Aboriginal Australians continued until the 1960s. ‘I view this material with a deep, personal hurt for my family and for all Aboriginal people’, Watson has said.

Jabiluka UO2 1979 is a video of a performance by artist Bonita Ely. She travelled to Jabiluka, Northern Territory, where the Mirrar community waged a decades-long campaign to prevent uranium mining on their land. The video addresses land rights, environmentalism and feminism, echoing broader themes of Australia’s counterculture.

Traditional landowners and allies are still protesting against land rights infringements by mining operations. In 2019 the Australian government permitted the Adani company to develop a coal mine that will endanger the Great Barrier Reef. Similarly, in 2020, the mining company Rio Tinto deliberately destroyed rock shelters in the Juukan Gorge which the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples have had continual connection to for 46,000 years.

Tracey Moffatt

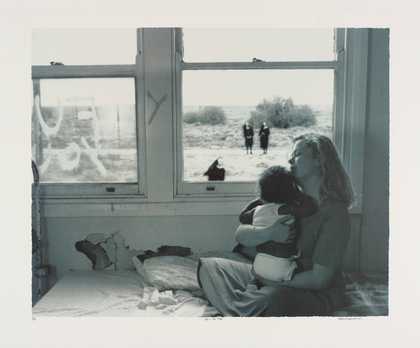

Tracey Moffatt

[no title] (1997)

Tate

Tracey Moffatt’s photographic series Up in the Sky 1997 depicts a town in the Outback. The images have a filmic quality, suggesting a hidden narrative to be pieced together by the viewer. ‘My narratives are usually very simple, but I twist it’, Moffatt explains. ‘There is a storyline, but … there isn’t a traditional beginning, middle and end.’

In a series of conflicting scenes, violence, isolation and despair contrast with joy and tenderness. Even seemingly innocent images suggest a hidden trauma. Details such as an Aboriginal baby in a town of mostly white people as well as nuns in habits relate the series to the physical and psychological damage experienced by the ‘Stolen Generations.’

From the 1910s to the 1970s, Australia’s government agencies forcibly removed children from their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. They were often placed in Christian missions. Despite a formal apology issued by the Australian government in 2008, those affected by the Stolen Generations policies continue to experience trauma, including loss of family, disruption of culture and disconnection to country.

Helen Johnson

Helen Johnson examines the legacy of British colonisation in Australia’s political framework, society and environment. Reflecting on her identity as a non-indigenous Australian, she states that ‘it’s important for the white people of Australia to reflect on our own cultural foundations.’

Introduced species, diseases and ecological disturbance are the focal point of Bad Debt. Images of foxes and rabbits overlay drawings of circus performers dressed as a cat and a horse - species that have caused widespread damage to Australia’s unique biodiversity. Smallpox particles are too small to be visible, yet their introduction by the British as well as other viruses from 1788 had a devastating effect on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The painting’s composition is based on the layout of Australia’s capital city, Canberra. This is one of the world’s few purposely designed cities. However, the planners ignored the Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri peoples whose land it stands on.

Seat of Power uses literal and symbolic images to refer to the continued relationship between Australia and Britain. Johnson presents this as ‘embodied in the fetishistic production of a replica of the Speaker’s Chair at Westminster that was gifted to the Australian parliament in 1926.’ At the centre, Johnson replicates an image of the British House of Commons from Manners and Customs of Ye Englyshe in 1849, a book of satirical sketches by Victorian illustrator Richard Doyle. She uses ‘images that acknowledge the corruption, sycophancy and greed of colonial culture that, to me, were emblematic of the male modes of power that were taken to Australia by the British.’