Gordon Bennett

Home Décor (Relative/Absolute) Flowers for Mathinna #2 1999

acrylic on linen

182.5 x 182.5cm

Collection: Museum of Contemporary Art, purchased with funds provided by the MCA Foundation, 2012

© The Estate of Gordon Bennett

1. He is one of the leading Australian artists of his generation

Gordon Bennett (1955–2014) worked for Telecom Australia before quitting his job at the age of thirty and enrolling in a fine arts degree at Queensland College of Art. His colourful and thought provoking conceptual paintings, prints, performance videos and installations draw on many different sources and styles. This included abstract expressionism and a dot aesthetic inspired by the Papunya Tula art movement of the Australian Western Desert. His artwork resist and debate racial stereotyping and is critical of Australia’s colonial history and postcolonial present. Major retrospectives of his work toured Icon and Arnolfini galleries and Heine Onstad Kunstsenter in Europe during 1999–2000, Australian State galleries between 2007–2009 and The Netherlands in 2012.

Writing in his ‘Manifest Toe’ in 1996, Bennett said:

If I were to choose a single word to describe my art practice it would be the word question. If I were to choose a single word to describe my underlying drive it would be freedom … To be free we must be able to question the ways our own history defines us.

2. His work challenges the concept of identity

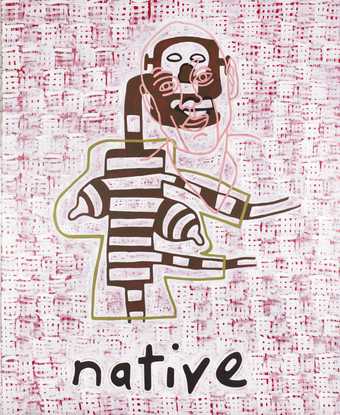

Gordon Bennett

Abstraction (Native) 2013

acrylic on linen

183 x 152.3cm

Collection: Museum of Contemporary Art, purchased with funds provided by the MCA Foundation, 2013

© The Estate of Gordon Bennett

Bennett was born in Monto, Queensland, in 1955 to an indigenous Australian mother and an Anglo Celtic migrant father. He first became aware of his dual heritage when he was a young teenager. He felt alienated by his Australian education and the representation of Aboriginal people in Western culture and as a result, began confronting the idea of identity in his own work. His playful yet powerfully political artworks borrow images from other artists and mix and re-contextualise elements from Western and non-Western art history. In Abstraction (Native), from the Abstraction series of 2010–2013, Bennett imposes the face of Australian politician and social activist Peter Garrett (formerly the front man of Australian rock band, Midnight Oil) onto an abstracted human figure. In his Welt series of paintings of the early 1990s, he painted over the created ‘scarified’ surface of Jackson Pollock inspired drip paintings in matt black. The textured surface references the colonial footprint of global black slavery. By quoting from a range of cultures and artistic styles, he questions and undermines colonial history and racist stereotypes.

3. He created a Pop Art alter ego

John Citizen

Interior (Tribal Rug) 2007

acrylic on linen

152 x 152cm

Collection: Private, Brisbane

© The Estate of Gordon Bennett

In 1995 Bennett began making work under the name 'John Citizen'. The pop art inspired paintings of the Coloured People and Interiors series seem glossier and less political than Bennett’s other work, but this is not the case. At first glance, paintings from the Interior series appear similar to the work of Patrick Caulfield and look like a brightly coloured pull-out from a lifestyle magazine. Look more closely, however, you can see paintings by the 'real' Bennett displayed on the walls. The persona of John Citizen partly represents 'the Australian Mr Average', but is also a kind of disguise for Bennett. It was another way for the artist to avoid being typecast simply as 'a professional Aborigine, which both misrepresents me and denies my upbringing and Scottish/English heritage'.

4. He wrote a letter to artist Basquiat, ten years after his death

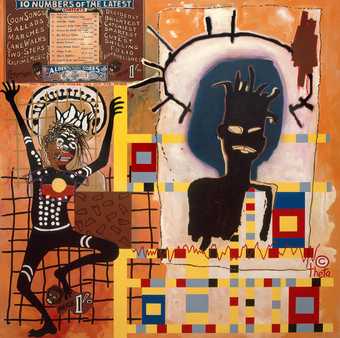

Gordon Bennett

Notes to Basquiat: Boogieman Blues 1999

acrylic on linen

182.5 x 182.5cm

Collection: Private, Adelaide

© The Estate of Gordon Bennett

In the late 1990s Bennett responded to the personal experiences and practice of Puerto-Rican Haitian-American artist Jean-Michael Basquiat by producing a series of paintings that referenced the style and appropriated motifs of Basquiat’s own art. He also wrote an open letter to the dead artist celebrating their cultural and artistic similarities, as well as their shared love of jazz, rap and hip-hop. Bennett conversed about his conceptual painting practice as 'based on the semiotics of ‘style’ and paint application, images and text, historical and contemporary juxta-position'. His intention in the Notes to Basquiat series is to 'highlight the similarities and cross-connections of our shared experience as human beings living in separate worlds that each seek to exclude, objectify and dehumanise the black body and person'.

In the open letter to Jean-Michel Basquiat, Bennett continues:

To some, writing a letter to a person post-humously may seem very tacky and an attempt to gain some kind of attention, even 'steal' your 'crown'. That is not my intention, I have had my own experiences of being crowned in Australia, as an 'Urban Aboriginal' artist – underscored as that title is by racism and 'primitivism' - and I do not wear it well. My intention is in keeping with the integrity of my work in which appropriation and citation, sampling and remixing are an integral part, as are attempts to communicate a basic underlying humanity to the perception of 'blackness' in its philosophical and historical production within western cultural contexts.

Bennett directly referenced the work of many other artists throughout his career, including Jackson Pollock, Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich and Vincent Van Gogh.

5. He thought of his practice as ironic ‘history’ paintings

Gordon Bennett

Possession Island (Abstraction) 1991

oil and acrylic on canvas

182 x 182cm

Collection: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Tate, purchased jointly with funds provided by the Qantas Foundation, 2016

© The Estate of Gordon Bennett

Bennett makes art that questions ‘accepted’ versions of history, often taking historical artworks as his starting point. His three paintings titled Possession Island are based on a 19th century etching by Samuel Calvert. The original image shows explorer Captain James Cook raising the Union Jack flag in 1770, claiming ownership of the entire eastern coast of Australia in the name of the British Crown. Bennett updates this image in Possession Island (Abstraction) by concealing the indigenous servant beneath the abstract and conceptual style of Kazimir Malevich. These shapes are coloured red, yellow and black referencing the Aboriginal flag and loss of a culture. Bennett is commenting on the devastating effects of colonialisation on Australia’s indigenous population.

Gordon Bennett's artwork is on display at Tate Modern in Artist and Society: Citizens.

Tate, The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) and Qantas are partners in an International Joint Acquisition Programme for contemporary Australian art. Gordon Bennett Possession Island (Abstraction) 1991 was purchased jointly by Tate and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia with fund provided by the Qantas Foundation, 2016.