Antony Cairns, LDN5_051 2017 © Courtesy of the artist Antony Cairns

Room 1

introduction

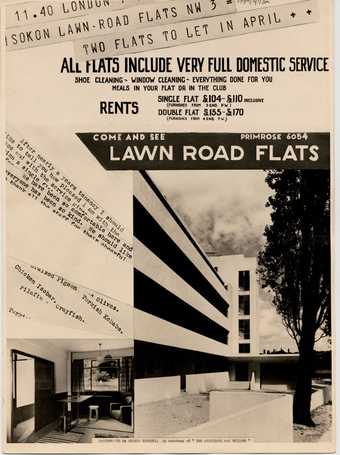

Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art, Tate Modern 2018

Install View

Photo: © Tate (Seraphina Neville)

Why should the inspiration that comes from an artist’s manipulation

of the hairs of a brush be any different from that of the artist who

bends at will the rays of light?Pierre Dubreuil

The world we see is made of light reflected by the things we look at. Photography records this light, holding and shaping these fleeting images. Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art explores the history of artists who have worked with light to create abstract work. These photographers prioritise shape, form and expression over recognisable subject matter. Some use the camera lens to transform reality. Others work with photographic materials to create images with little obvious reference to the real world.

Shape of Light reveals photography’s role in a wider history of abstraction. The photographic artists in the exhibition have engaged with advances in abstract art across a range of art forms; from painting and sculpture, to film and installation. At times these photographers have responded to new discoveries by their peers working in different media. Occasionally they have pre-empted them.

Throughout the exhibition key paintings and sculptures reveal the changing relationship between photography and abstract art. We start in a period when the essential qualities of painting, sculpture and photography were clearly distinct. We end with art from today, at a time when artists no longer define themselves by their choice of medium. They are free to shape light however they choose.

Room 2

camera work

Unless photography has its own possibilities of expression, separate from those of the other arts, it is merely a process, not an art.

Alfred Stieglitz

In 1903, American photographer Alfred Stieglitz launched Camera Work, a journal promoting photography as a fine art. Two years later Stieglitz opened 291, a gallery in New York with the same aim. Both Camera Work and 291 provided a platform for debate about photography and modern art. Encouraged by fellow photographer Edward Steichen, Stieglitz began promoting work by European painters and sculptors. He showed photographs alongside these works in other media, including sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, like the one displayed here. Stieglitz hoped to encourage audiences to ‘discuss and ponder the differences and similarities between artists of all ranks and types’.

The relationship between different art forms influenced Stieglitz’s views on photography and the direction it might take. Following an initial commitment to images that created painterly effects, he began to take photographs which embraced qualities essential to the medium. These sharply focused, high contrast images reveal the form and structure of his subjects. This approach became known as ‘straight photography’. Photographers like Paul Strand pushed this further. In Strand's compositions everyday objects are no longer immediately recognisable; he called these images ‘abstractions’. In 1917, Stieglitz dedicated the last issue of Camera Work to Strand, whose photographs came to exemplify this new direction.

Room 3

new vision

Edward Ruscha

Gilmore Drive-In Theater - 6201 W. Third St. 1967

Courtesy Ed Ruscha and Gagosian Gallery

© Ed Ruscha

We have – through a hundred years of photography and two decades of film – been enormously enriched… We may say we see the world with entirely different eyes.

László Moholy-Nagy

In the 1920s artists began to use the camera lens to present a new vision of the world. This new way of looking emerged in Russia through the work of figures such as Aleksandr Rodchenko, and in Germany through the methods of the Bauhaus. Opened in 1919, the Bauhaus was a revolutionary school of art. Like similar groups working in Russia it aimed to bring art back into contact with everyday life. It encouraged its international students and teachers to work together. All art forms were treated as equal, and artists and designers worked across different media. The status of photography was elevated to that of painting and architecture. Many viewed it as the ideal medium of modernity.

Hungarian artist and theorist László Moholy-Nagy was one of the Bauhaus’s most influential teachers. A painter with no formal photographic training, he was introduced to the medium by his wife, the photographer Lucia Moholy. Together they set out to create an independent photographic language. They recognised the medium’s ability to capture the emblems of modern life, from skyscrapers to the inner workings of machines. Their images incorporated strong effects of light and shadow to reproduce the world in sharp detail.

Moholy-Nagy encouraged experimentation in the darkroom and took photographs that played with perception through extreme angles, tilted horizons and fragmentary close-ups. This exploration of techniques and processes spurred a generation of photographers to break old habits of visual representation. By looking closely and exploring new perspectives their images hovered at the limits of abstraction, presenting a new vision of the modern world.

room 4

objects and constructions

Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art, Tate Modern 2018

Install View

Photo: © Tate (Andrew Dunkley)

I think that, instead of producing a banal representation of a place, I’d rather take my handkerchief out of my pocket, twist it to my liking, and photograph it as I wish.

Man Ray

The photographs in this room were made in the 1920s and 1930s and use objects to produce photographic abstractions. In these still life arrangements surprising combinations and close up views make everyday objects strange. These artists also defamiliarise subjects by deconstructing the photographic print through collage and photomontage. Such techniques emphasise the volume, shape and form of familiar things. In doing so they encourage us to focus on

their abstract qualities.

Several images shown here were made without a camera. These photograms or ‘rayographs’ are created by laying objects directly on to photosensitive paper. Identifiable items are mixed with mysterious forms to create strange abstractions that look unlike anything we might find in the world around us. Other images were created by photographing compositions constructed from paper and everyday objects, their arrangement playing with scale and spatial awareness.

These photographs have visual connections with the collages and sculptural reliefs of artists such as Jean Arp. In the 1930s, Arp made work using abstract forms that resemble nature. The photographers in this room use natural forms to create abstractions. By presenting objects as fragments, traces, signs, and memories, they move beyond their medium’s ability to reproduce reality. Instead these artists explore photography’s capacity to create new realities through the manipulation of light, chemicals and paper.

room 5

finding form

Man Ray

Unconcerned Photograph 1959

© Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

My only aim was to express reality, for there is nothing more surreal than reality itself. If reality fails to fill us with wonder, it is because we have fallen into the habit of seeing it as ordinary.

Brassaï

In 1924 French poet André Breton published the first Surrealist Manifesto. Surrealism hoped to revolutionise human experience by rejecting a rational vision of life in favour of one that valued the role of the unconscious and dreams. Its writers and artists found beauty in the unexpected, the overlooked and the uncanny.

The movement embraced photography of all kinds, from found images to conscious abstractions. Photography offered the opportunity to look closer at the world, uncovering the latent surrealism in everyday life. In the hands of surrealist artists, photography was liberated from the ordinary task of description. Their images rendered familiar subjects strange and revealed unexpected resemblances.

The photographs shown here find form in darkroom experiments and create abstractions through the distortion of the human body. These artists employed mirrors and extreme cropping, painted with chemicals, produced photograms and used double exposures. The resulting images encourage us to engage the creative powers of our imagination.

room 6

drawing with light

Jackson Pollock

Number 23 1948

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2018

I wanted to experience light in the same way you’d experience a brush and pigment and learn how to apply it.

Nathan Lerner

The word photography comes from ‘phōtos’, the Greek for light, and ‘graphé’, meaning drawing. From the first announcement of themedium in 1839, photographers have used light as a tool of graphic expression. The photographs shown here harness the medium’s essentials: photosensitive chemicals trace the movement of light and the duration of exposure on to paper.

These works draw on ideas of automatism, creativity that is not consciously controlled. The surrealists believed that by applying chance to mark making artists could be released from the constraints of rational thought and become free to express their unconscious. In the 1940s experiments in automatism took place across different media. Action painters such as Jackson Pollock explored free movement to create works celebrated for their gestural mark making. Photographers moved their cameras and light sources to create dynamic images that embraced motion blur.

Whether through automatic drawing, the splatter of paint across a canvas or the movement of a sparkler in the night sky, it is the human compulsion to make spontaneous gestures that links the works in this room. They demonstrate that abstraction comes as naturally to photography as it does to any other medium.

room 7

subjectivity and expression

The making of a picture will always take place in the realm of the conscious, the degree of consciousness depending on the nature of the photographer’s personality.

Otto Steinert

In the 1940s German photographer Otto Steinert became interested in the expressive potential of his medium. Steinert was part of a generation of German photographers keen to continue the ideas that had emerged from the Bauhaus before the Second World War. They called themselves fotoform and aligned themselves with modernist ideals. The group promoted innovation and experimentation with form and an emphasis on materials and processes. Brazilian photographer Geraldo de Barros developed similar ideas independently as ‘fotoformas’.

Steinert began to look beyond the formal qualities of photographic images. He felt that the creative decisions taken by the photographer – from choice of equipment, to perspective and printing technique – provided the photographic subject with new meaning and significance. In 1951, Steinert organised an exhibition to promote this way of looking. He called it Subjective Photography. He accepted any style of photograph, from cityscapes to darkroom abstractions. The exhibition featured photographers from across the world and travelled internationally.

The broad range of artists who participated reflected a shared consciousness across continents. Similar projects in other countries, touring exhibitions and international publications suggested many photographers were looking beyond the formal concerns of previous generations. Some continued to make images with a strong visual connection to modernist photographs from the 1920s and 1930s. But these new works celebrated the medium’s ability to express the

subjective experiences of the photographer.

room 8

surface and texture

When a painter paints a picture it can be immediately abstract. They have no problem making abstractions. A band of paint is simply a band of paint. It is not derived from realistic photographic images. When a photographer makes nature abstract, an attempt is made to transform a realistic scene into an abstraction.

Aaron Siskind

This room presents found abstractions lifted from nature and the urban environment and repurposed for the gallery wall. Through selection, framing and emphasis of tone and contrast, photography casts a new light on the everyday. These photographs encourage us to look closer. They present peeling paint and scratched surfaces as worthy of aesthetic appreciation.

These photographic 'found paintings' visually connect with the tangles of line and colour associated with abstract expressionist paintings from the 1940s and 1950s. Photographers were central to the developments in American art in this period. Works by figures such as Aaron Siskind were exhibited alongside paintings and assemblages of found objects. Many noted the resemblance between images of street markings and graffiti and the gestural brush strokes of contemporary painters. However, in using the world around us to make images that highlight texture and surface, photography retains a sense of subject that painting does not. These photographs have more in common with assemblage, the repurposing of everyday objects as art.

room 9

the sense of abstraction

Alvin Langdon Coburn

Vortograph1917

© The Universal Order.

The many techniques and devices apparent in the exhibition are not new. What is significant is the fresh surge of interest in using familiar tools of the photographic medium to produce works whose sole function is to delight – or affront – the eye.

Grace Mayer, curator of The Sense of Abstraction

This room is a homage to and partial recreation of The Sense of Abstraction, a photography exhibition which opened at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York in 1960.

The works included ranged from ‘accidental’ abstractions to experimental photographs that sought to break new ground. The variety of images spoke to photography’s complex relationship with abstract art. In fact, some of the artists shown questioned their inclusion. American photographer Minor White wrote to curator Grace Mayer to express his concerns: ‘I feel that these photos of mine that you have chosen are not abstractions in any sense whatsoever. True they resemble paintings that go under this title, but this is coincidental, not intentional.’

The exhibition included artists from Asia, Europe and North America. Its international scope revealed both the shared interests and unique concerns of photographers across the world. The MoMA curators grouped works with similar formal qualities and technical ambition. Several groups from the 1960 show are recreated here and a number of series are shown in the order they were displayed at MoMA. In highlighting the diversity of photographic abstraction, the exhibition paved the way for a further 60 years of experimentation.

room 10

optical effects

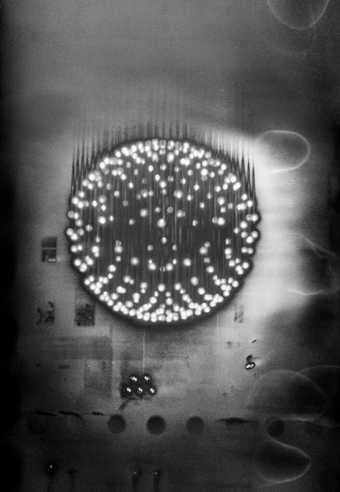

Naturally, while working in the darkroom I could not resist the magic of light, its miraculous ability to create an image of its own on photographic paper or plate – an absolute photography.

How little is needed for its creation!

Běla Kolářová

Emerging in the 1960s, op art used geometric forms to produce optical effects. These works suggest movement and play with our perception of space. The photographs shown here create similar effects to those the op artists produced through paint.

These images have a direct relationship with the experiments that produce them. Photographers created optical effects in the studio and the darkroom before capturing the results on photographic paper. They manipulated light through movement, moving materials and equipment, both by hand and using mechanical means, such as turntables. By passing light through objects and filters they could change its direction and intensity. Instruments such as oscillographs, which visually record electrical currents, were used to produce images with abstract curving lines.

Many artists worked at the edges of art and technology. Photographers developed processes that attempted to remove the human element from the act of making, setting in motion processes of creation which would continue in the absence of a ‘maker’. Photography was no longer limited to reproducing images, it could generate new ones.

room 11

minimalism and series

Maya Rochat

A Rock is a River (META RIVER) 2017

© Maya Rochat

I had no restrictions on how to approach photography. I felt free to incorporate any of these concepts into my thinking. I wasn’t breaking rules; I was actually making up my own.

Barbara Kasten

The artists in this room arrange objects, construct scenes and find order in the world around us. Produced in the 1960s and 1970s, their works reduce what we see to its essentials and prioritise form over creative expression.

Several works displayed here respond to the themes of minimalism. Minimalism claims that art should have its own reality and not be an imitation of anything else. Minimalist artists make no attempt to represent the outside world, their experiences or emotions. They want the viewer to respond only to what is in front of them. This concept can be problematic for photography, a medium that is by nature representational. Many of the photographers shown here engage with the aesthetic simplicity of minimalist art, presenting carefully selected volumes, shapes and lines. They focus our looking on the forms within the image so that the source or subject matter

becomes irrelevant.

Other images engage with serial art and conceptual practices, which often involve following strict sets of rules to determine their outcome and composition. In adhering to processes, artists can create art without personal expression. By photographing and rephotographing their subjects, they are also able to experiment with different permutations. These works create order through repetition and highlight the form and structure of the world around us.

room 12

contemporary abstraction

How can you be a pioneer in your own time if you’re copying the successes of the past? How can you make an impact with images, when everyone sees so many? I want my images to

have a contemporary context. I want them to be images for today.

Maya Rochat

The works in the final room of the exhibition range from minimal compositions that demonstrate control and order, to wild abstractions that embrace chance and accident. These abstract works encourage us to engage with the artwork as a whole, including the process of its production.

All of the artists shown here have made work following the launch of the first portable digital camera in 1975. The introduction of digital technology had a profound impact on photography's place in the art world. Where a commitment to the purity of the process was once the key to creating art, contemporary artists have dispensed with boundaries between mediums. Digital technology offers artists a new set of tools to work with, from computer programming to innovative printing techniques.

These artists expand the possibilities of photography. They embrace ways of working that were once seen as contradictions. They use darkroom processes alongside digital technology, question the notion of the original and copy, and follow controlled processes while accepting

the accidents that come with experimentation.

For many of the artists in this room, the process of production is a performative act that becomes part of their artwork. They adopt all modes of image making at their disposal, creating work that can no longer be reduced to the title of photographic abstraction. Instead their work reveals photography’s new place in the world.