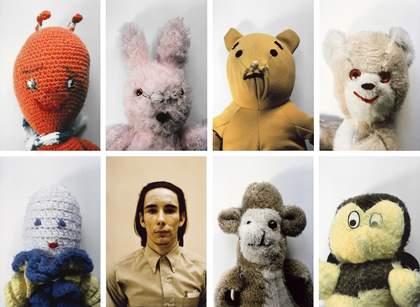

Mike Kelley Ahh...Youth! 1991/2008 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY & DACS, London.

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Modern

Mike Kelley Ahh...Youth! 1991/2008 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY & DACS, London.

Mike Kelley and Don Krieger Spirit Voices 1978. Performance at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE)

The earliest performances were just groups of demonstrations of objects; by talking about them, their meanings changed....Then they started becoming subsumed by the language and that’s how the long performances developed where the language became the controlling factor...

Mike Kelley

This room features work Kelley made while studying at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). The school was known for its conceptual approach, prioritizing art theory over the making of objects. Kelley was also exposed to the experimental live performance and feminist art scenes of 1970s Los Angeles, which inspired him to channel a range of contesting ‘voices’ or viewpoints in his work.

Kelley first played with language in his Birdhouse sculptures (1978), which are accompanied by titles and diagrams that suggest alternate meanings. Describing them as ‘working-class minimalism,’ he began seeing these objects as prompts for conversation and used them to make live performances. He realized that the longer he spoke about the objects, the more their meanings changed. At times he introduced recordings of his own or other voices. Kelley’s performances became an important part of the LA art scene, their absurdist and ritualistic logic described as: ‘classroom lectures with the sense taken out of them.’

Kelley’s combination of performance and language found another outlet in The Poltergeist (1979), which relates to his ‘ghost and spirit’ concept. The Poltergeist plays on photography’s association with truth, and the transitional line between the real and imagined.

Monkey Island a warm sweet-smelling wind blows over two hemispheres cut in a pheromone sea...

Mike Kelley

Monkey Island 1982–3 marks an important moment where Kelley began to develop his performances into gallery-based installations. Combining image, text and sculpture in an unconventional manner, Kelley described the work as:

an epic poem... a sailor’s tale. It’s a physiognomic landscape travelogue that seems to dwell mostly in the sexual region

Mike Kelley

In this project, Kelley attempts to plot out an internal world of artistic imagination. The work is partially informed by North American psychologist Harry Harlow’s 1950s experiments into mother-child bonding in primates. Another reference is a photograph of the ‘island’ populated by monkeys, which was an attraction at Los Angeles Zoo. The play with perspective and viewpoint Kelley first explored in his early performances is developed into an expansive, quasi-surrealist project.

The X-shaped motif that recurs throughout the installation relates to the chain-link fence through which Kelley saw the LA ‘monkey island’. It explores various forms of division, connection, and expansion, acting as a metaphor for the way the mind separates and categorizes knowledge, memory, and experience. The apparent simplicity of such a system is interrupted at various points by the primal influence of the monkeys.

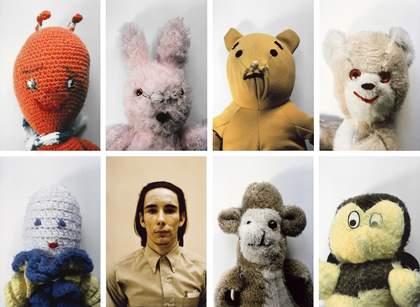

Jim McHugh portrait of Mike Kelley as The Banana Man,1983, with (in the background) Last Tool in Use, 1977

I’m often working ‘in character,’ so if there is a psychology, it’s a fractured, schizophrenic one. The heroic individual is replaced by a kind of multi-individual. I’m in there, but I’m trying to make it difficult to tell who this person is. It’s important for those looking at the work to remember that it is art - it’s about posturing. The viewer must at least suspect that I am not the thing I claim to be.

Mike Kelley

Kelley adopts different roles in his work, from teenagers and janitors to the Banana Man, a character from children’s TV. He aimed to both resist and invite biographical readings to complicate the idea of a single authorial voice or fixed identity. He was especially interested in the developmental stage of adolescence as a liminal space between childhood and adulthood. The youth subcultures Kelley engaged with also tended to challenge societal expectations through the use of provocative imagery. For Kelley, the world of art represented a similar space where ideas could be tested, deconstructed, and reimagined. He explained:

An adolescent is a dysfunctional adult, and art is a dysfunctional reality, as far as I am concerned.

Mike Kelley

Throughout his life, Kelley engaged with radical leftist politics and counter-cultural movements in art and music. In these works from the 1980s, he subverts images, caricatures, and symbols of identity from collective US cultural and historical memory, and embraces a politics of failure. Motifs borrowed from heavy metal music iconography are deployed to ironic effect, and schoolchild-style doodles reveal a critical attitude towards US political history and a persistent deflation of symbols of power.

What I was trying to do was to have something that you looked at and said, “That’s normal – that’s me.” ... I wanted people to fall into it first, and then go, “Something’s wrong.” But it’s too late, you’re already in there.

Mike Kelley

The title of Kelley’s breakthrough project Half a Man (1987–91) refers to his notion of the adolescent as a ‘failed’ or as-yet unformed adult. Using found objects and low-cost materials often associated with craft, Kelley explores how art can be a container for systems of belief and ideology.

The earliest works are felt banners similar to those seen in churches and schools, but with slogans that subvert their usually uplifting messages. The Garbage Drawing series (1988) isolates comic book illustrations of waste, pointing out how society usually tries to eliminate dirt. In 1987, Kelley had begun to use old stuffed toys, found in thrift shops, as a material. Interested in these objects’ status as hand-made gifts, Kelley questions if children are obligated to love those who labour over the toys: the exchange of labour for love.

Craft had been reclaimed by feminist artists in the 1970s as an important means of artistic expression. Kelley engaged with craft to resist the dominance of modernist art, which he saw as inherently masculine in its fixation with order and cleanliness. He also disrupted the austere order of the gallery environment by introducing objects that referenced bodily functions, dirt, and childhood. Kelley became interested in how certain cultural forms are either ‘allowed’ or ‘repressed’. The theme of repression would come to influence his later projects.

Kelley’s use of stuffed toys in his artworks led some critics to assume that they were about an unhappy childhood. Despite stating this was not his intention, Kelley did not share his real autobiography and said:

There was simply nothing I could do to counter the pervasive psycho-autobiographic interpretation of these materials. I decided, instead, to embrace the social role projected on me, to become what people wanted me to be: a victim. Since I am an artist, it seemed natural to look to my own aesthetic training as the root of my secret indoctrination in perversity, and possibly as the site of my own abuse.

Mike Kelley

In 1995, Kelley created a large architectural model he called Educational Complex, which explores the role that institutions have in shaping identity and behaviour. The original work is not on display, but images are shown on a slideshow. Using architectural plans, photos, and site visits, Kelley recreated the buildings where he had been educated, including his family home. The areas he had forgotten were represented as blank blocks with no architectural detail, which he said represented sites of both repression and imagination.

The work is related to Kelley’s interest in publication fascination with ‘repressed memory syndrome.’ This theory suggested any neurosis or gap in memory could be the result of a traumatic event that requires therapy to uncover. However, the therapy was criticized for using leading questions that created false memories. Since then, modern neuroscience has enabled more work to be done on how memory operates in the body.

The mobiles and drawings from the Repressed Spatial Relationships Rendered as Fluid series explore similar themes, as does Sublevel (1998) in the next space.

The sublevel is the basement of CalArts ... The sublevel must have been an incredibly torturous arena to engender such a wide blanket of forgetfulness. But one spot seems especially ominous, more terrible than the rest: the ultimate zone of unspeakable horror.

Mike Kelley

In this room, Kelley explores how the mapping of a territory connects to memory. The central work Sublevel (1998) is a model of the basement of CalArts, where he had studied in the 1970s. The spaces that Kelley couldn’t recall from memory are lined with pink crystal resin. Surrounding the model is a ‘sub-sublevel’ tunnel that audiences could originally crawl into. Based on a room depicted on the CalArts floorplan with no obvious entryway, Kelley describes the tunnel as ‘a place of nonexistence.’ Symbolically, Sublevel represents a subversive antidote to the above-ground activities of the arts institution.

While it’s no longer possible to access the tunnel, a photo nearby gives an idea of the interior space. A metal room contains various phallic objects arranged on a shelving unit, referencing UFO abduction stories in which aliens probe humans with similar devices. The work stages a site of hidden memories and repressed desires, underscored by the symbolism of the pink colored crystals, as Kelley explained:

Why pink crystal? Because, as everyone knows, regardless of meaningless, exterior coloration, it’s all pink inside.

Mike Kelley

To tell you the truth, I’m not interested in the story; I’m not a fan of Superman comics. I just like the idea of being burdened with one’s past. Superman, as a baby, is sent away from his home planet, which blows up; and then, later in life, he’s saddled with the responsibility to watch over his hometown forever. What a horrible scenario - but everyone is stuck with their past.

Mike Kelley

Kelley continued to explore the relationship between memory and architecture in his Kandor series (1999–2011). The works feature different depictions of the city of Kandor, the capital city of Superman’s home planet Krypton. Kandor survives the destruction of Krypton by being shrunk and preserved under a glass bell jar by the supervillain Brainiac. Superman eventually discovers the shrunken city and transports it to his secret base but is unable to restore it to its original size. The resulting alienation from his home introduces a melancholic side to his character.

Kelley was interested in how cartoonists over the decades depicted Kandor in different ways. This made it impossible to accurately reconstruct, which Kelley described as ‘an appropriate model of memory’s elusive nature.’ He recreated a select group of 20 illustrations of Kandor from his research, using drawing, lenticular light boxes, sculpture, and video. As an inaccessible reminder of an earlier life, Kandor speaks to the fascination of memory about one’s past, but the impossibility of returning.

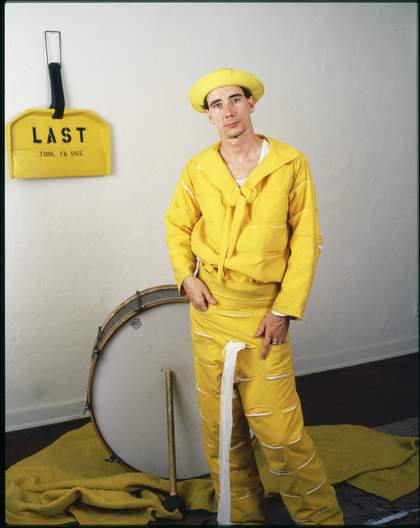

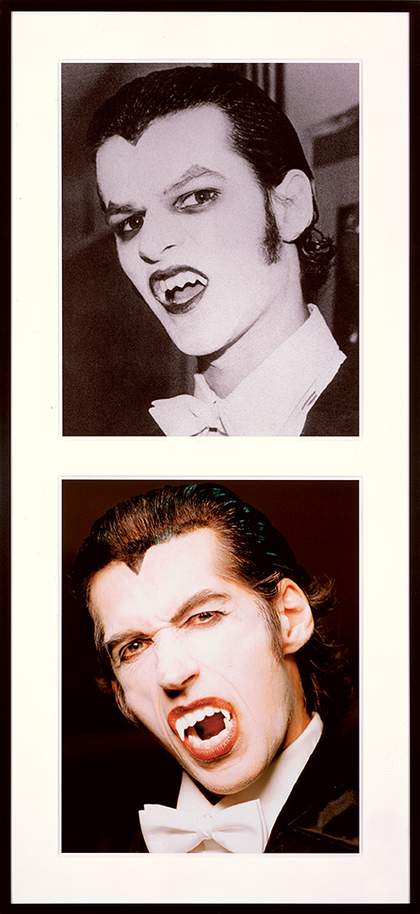

Mike Kelley Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #4 (Boss Vampire), 2004-05 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY & DACS, London.

The folk entertainments I represent are true in the sense that most people have done or experienced such things themselves during their lifetime. I don’t see them as simply shallow any more than I see ‘false memories’ as shallow. They are truly felt experiences. Movies and pop songs are similarly real on the emotional level. I’m playing with the equivalence of art and true recollection.

Mike Kelley

Kelley’s interest in working-class culture, popular entertainments, subcultural traditions, and socially accepted practices of ‘deviance’, such as Halloween, led to his most ambitious project: the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction series (2000–11). Consisting of multiple video installations, each part was meant to represent ‘screen memories’ – a psychoanalytic concept where unpleasant memories are repressed or hidden by seemingly benign recollections. The ideas emerge from the ‘blank’ architectural spaces of his Educational Complex and Sublevel projects.

To create the works, Kelley restaged US high school yearbook photos depicting extracurricular activities into performances for video. Some of the scenarios are playful, while others explore violence and childhood trauma. Kelley wrote and worked across every aspect of the productions, collaborating on the music with Scott Benzel (b.1968). The videos were then presented as installations that featured the stage-set, costumes, and props alongside the original yearbook photo.

The first large presentation of the project was as the exhibition Day Is Done at Gagosian Gallery, New York, in 2005. He described it as a ‘fractured’ musical, an experience similar to channel-surfing while watching TV. He would continue to work on the project until his passing in 2012.

The video piece Empty Gym (2004–5) records the concluding scene of Kelley’s Day Is Done project. The all-seeing eye of the camera pans over the space where many of the extracurricular activities have taken place.

This final section of the exhibition also presents the trace of Kelley’s hand through a selection of notes, sketches, and scripts from his various projects. It provides an insight into his working process as he developed movements for his performances and designs for artworks and costumes. It culminates with the original script for the unrealized performance Under A Sheet/Existence Problems, which features Kelley’s text about ‘ghosts and spirits.’

A spiritual connection also haunts the two videos Bridge Visitor (Legend-Trip) (2004) and Judson Church Horse Dance (2010), the latter on display in the concourse space outside. Bridge Visitor is an experimental video based around a local legend in Kelley’s hometown where a spirit is invoked by fire-bombing a bridge. He said:

Bridge Visitor draws upon ‘legend trip’ activities of my youth. Legend trips are adolescent group ritualistic activities, often in response to local folk tales [which] act as instigators for shared, potentially dangerous or frightening experiences.

Judson Church Horse Dance (2011) documents Mike Kelley’s last live performance. It is made up of three scenes from the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction series. The title references the Judson Church in New York, where the performance took place. In the 1960s, the space was used for experimental dance performances that emphasized everyday gestures like walking and running. Kelley plays with this legacy, as well as his own roots in performance.

The video features pantomime horses, basketball games, and Christian religious pageantry, including the ‘May Queen,’ to create a modern-day folk ritual, devoid of hierarchy and with hope for renewal. It is a moment of culmination in Kelley’s work, as an artist who continually sought to reconstruct cultural narratives into alternative artistic rituals.