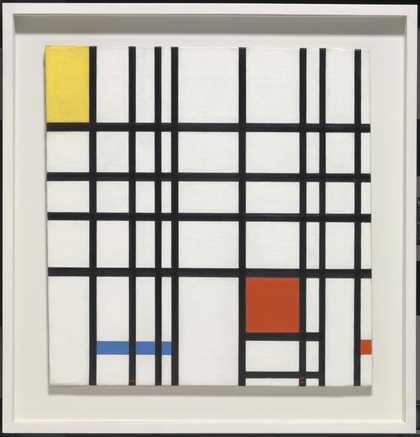

Piet Mondrian

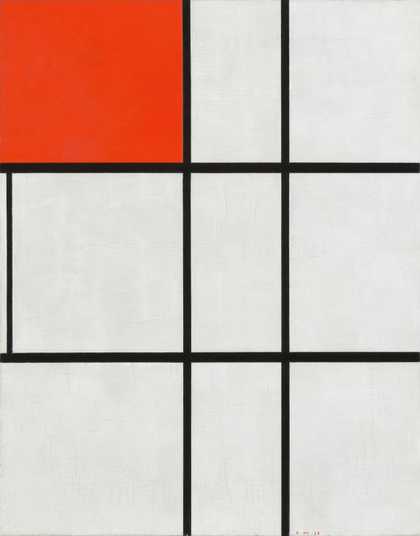

Composition B (No.II) with Red (1935)

Tate

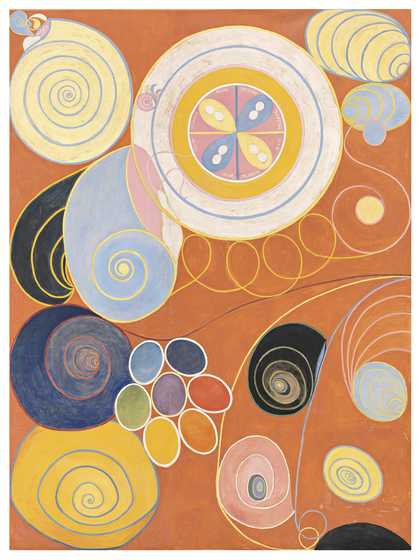

Hilma af Klint, Group 4, No 3. The Ten Largest, Childhood 1907. Courtesy The Hilma af Klint Foundation

Need a bigger font size of the exhibition guide? Download the large print version [PDF 840Kb]

1. Rooted in Nature

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) and Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) began their careers as academically trained landscape painters in the late nineteenth century, before developing radically new models of painting in the twentieth century. Although they did not know each other – or of the other’s work – this exhibition explores how they both developed the possibilities of abstract art, moving away from the conventions of representation they were taught.

During their careers, new technologies such as the microscope, radiography and photography were challenging human perception. The evidence of worlds invisible to the human eye catalysed shifts across science, spirituality and the arts. Rather than seeing af Klint and Mondrian’s abstract paintings as simply a violent rejection of natural appearances, their processes of making art are presented here as a way of thinking through nature. In their own ways, each artist was creating an abstract language that could express art’s interconnectivity with all forms of life. Seen from today’s perspective of environmental and planetary crisis, their close attention to such fragile relationships is even more relevant.

The exhibition dedicates rooms to the individual artists as well as uniting them through shared themes or motifs. At the centre of the exhibition is ‘The Ether’, inspired by the nineteenth century notion of an invisible energy connecting all things. Here, you are invited to immerse yourself in the artists’ cultural contexts and reflect on the creative circles that surrounded them. Seismic social, technological and artistic advancements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries encouraged many to question the nature of the universe. This is a space to consider how developments across different spheres of knowledge were taken up by the artists, fuelling their own artistic developments and outlooks on the world.

Landscape Painters

In 1882, af Klint joined the Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, where she studied for five years. Women had only begun to be accepted at the academy in 1864 and often still faced barriers to their careers. While studying, af Klint became well known for her landscape and portrait paintings, establishing herself as a respected artist. She would continue to produce paintings in this tradition even as she was making her abstract works. Later, in 1910, she joined the Swedish Society of Women Artists, serving as its secretary.

Mondrian studied at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, from 1892 to 1897. He was associated with the ‘Hague School’ of realist painters during a period of renewed energy and experimentation in Dutch painting in the second half of the nineteenth century. Their work was characterised by muted colours, loose brushwork and textured surfaces.

2. Evolution

This room brings together works by both artists, exploring the theme of spiritual and artistic evolution. In their Evolution works, af Klint and Mondrian experiment with symbolism through their choice of motif, colour and form.

Domburg, on the island of Walcheren in the Dutch province of Zeeland, became an artists’ community, known for its distinctive landscape and the quality of light. Mondrian first visited in 1908 and spent every summer there until 1914. This was an important phase in his quest to find his own visual language, involving experimentation with colour, style and technique. Domburg’s towers, in combination with dune scenes and seascapes, eventually led Mondrian to the focus on horizontal and vertical principles that are characteristic of his later abstract work. During this period, he painted the Evolution triptych. It has been seen to represent humanity’s progress from the physical towards the spiritual realm using symbolism from Theosophy, an esoteric movement that interested both artists.

Af Klint’s works in this room from 1908 represent humanity’s ascent to a higher spiritual state. She employed a colourful symbolism which recurs in her other works, including the spiral or snail to represent evolution. This series demonstrates how af Klint experimented with several visual languages within a single work, from symbolism and organic forms to abstraction. The titles are based on a system she was developing, where numbers correspond to certain geometric shapes, which refer to different aspects of the world and the cosmos.

The Paintings for the Temple

The WUS/Seven-Pointed Star Series, Group VI, The Evolution are part of The Paintings for The Temple, which af Klint referred to as her ‘greatest commission’. Between 1906 and 1915, af Klint created works that she believed were commissioned by her spiritual guide, Amaliel. Amaliel was one of the five guides, or ‘High Masters’ – beings thought to exist on a higher plane of consciousness – who communicated with af Klint and her spiritual collective, The Five, or in Swedish, ‘De Fem’. The commission eventually consisted of 193 works in several series, many of which are displayed in this exhibition.

3. Metamorphosis

The depictions of flowers in this room demonstrate each artist’s close observation of nature and its biodiversity.

From the late 1890s, Mondrian was mostly drawing, painting and exhibiting single flowers. He would paint blooming and wilting flowers as a way of tracing natural processes over time. Af Klint sometimes depicted a plant at two stages of its life, in spring and summer – her own meditation on cyclical patterns in nature. The ‘unfinished’ state of drawings by both artists resonates with the transience of their subject matter.

Mondrian’s preference for painting cultivated flowers, like lilies and chrysanthemums, contrasts with af Klint’s interest in plants native to the Nordic countries, such as cornflower and sea thrift. Her choice of watercolour on paper, as well as the arrangements of the plants on the sheet, show her familiarity with the conventions of botanical drawing. In the nineteenth century, botanical illustration was one of the few professional artistic activities open to women, and many, like af Klint, became skilled in this area.

Both artists moved beyond realistic representations of flowers. While af Klint would continue to engage with their deeper spiritual meanings, Mondrian explains ‘I enjoyed painting flowers, not bouquets, but a single flower at a time, in order that I might better express its plastic structure’. Their early immersion in the language of plants and the vegetal world offered each artist a means to articulate correspondences between microcosm and macrocosm – the idea that the structure of the cosmos is mirrored in the smallest living entity.

4. The Tree

The tree became a focal point for Mondrian and af Klint. Mondrian painted a series of trees between 1908 and 1911, and af Klint spent two years working on The Tree of Knowledge from 1913.

Af Klint’s series draws on a concept common to many mythological and religious traditions. The ‘axis mundi’, often described as the ‘world tree’, is a form that connects every part of the universe, from microcosm to macrocosm. In Norse mythology, the Yggdrasil is an ash tree at the centre of the cosmos, reaching to the heavens as its roots extend deep underground. In this series, af Klint combined the precision of botanical and scientific diagrams with ornamentation inspired by art nouveau – a decorative movement that used fluid, sinuous lines based on vegetal forms.

After travelling to Paris in 1911 and encountering cubism, Mondrian began reworking drawings and paintings of trees. Cubism was a radical new visual approach of breaking up objects and figures into distinct planes, emphasising the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. In The Red Tree, Mondrian painted a tree not as an element of the real world but as a ‘plastic expression’ – the energetic brushwork of the branches appears to celebrate the act of painting itself. In later trees, the trunk and branches are condensed to a network of verticals and horizontals, as Mondrian focused on distilling the image to the tree’s essential forms.

In many cultures and thought systems, trees are connected to mystical forces beyond the visible world. Focusing on the structure of the tree enabled the artists to explore these delicate life forces in their own ways.

5. Dynamic Colour

Mondrian and af Klint experimented in distinct ways with the dynamic relationships of form and colour to express the ‘universal’.

During summers spent in Domburg, Mondrian gradually refined his depictions of the towers and sea views until they dissolved into complete abstraction. He saw the verticals as the ‘male’ principle, representing the spiritual, and the horizontal as expressing the ‘female’, material principle. From 1914, Mondrian’s work consisted of horizontals and verticals that did not intersect, as seen in the paintings in this room. His ultimate goal was to ‘plastically express’ a universal harmony based on the balance of oppositional forces.

Af Klint painted the The Eros Series in 1907. She used light, pastel colours and elegant lines accompanied by letters and text. Linear diagonals evolve into dynamic forms reminiscent of flowers, leaves, or ovals. All the elements in this series appear to be designed to balance opposing ‘male’ and ‘female’ forces: the use of the contrasting colours blue and yellow, the letters AO (alpha and omega), and the Swedish words Asket (ascetic) and Vestal. Af Klint often used these names interchangeably in reference to herself and her collaborator Anna Cassel in her notebooks, suggesting a fluidity of gender or a unity between masculine and feminine. She may have taken the series title from Greek mythology, where Eros is the god of love. In the Roman poet Ovid’s text ‘Metamorphoses’, we encounter Eros in the tale of Cupid and Psyche, which is about overcoming obstacles to eventually achieve the ultimate union in a sacred marriage.

6. World Religions

In 1920 af Klint created Series II, a group of works on different religions. In a reduced abstract language of segmented circles, she visualises various religions at particular points in their development. Circles and crosses orbit, collide with and bisect larger geometries. Series II can be seen as part of af Klint’s ongoing project to work out the relationships between external forms and their underlying forces.

The Theosophical Society was an extensive transnational network that made the translation and dissemination of texts a key part of their expansion. Their publishing technologies were often based on new channels of communication used to support Britain’s imperial activities in India. In keeping with the theosophical principle that all religions are connected by a core spiritual truth, affiliated periodicals like The Theosophist, The Path, The Lamp and Lucifer regularly published articles on world religions. The ideas moving through these networks proved compelling to many artists and writers who encountered them. In 1904, af Klint joined the Stockholm lodge of the Theosophical Society, Adyar (named after the place where it was headquartered) and Mondrian joined the Theosophical Society in Amsterdam in 1909.

In his sketchbooks of 1912–14 Mondrian wrote, ‘All religions have the same fundamental content; they differ only in form. The form is the external manifestation of this content and is thus an indispensable vehicle for the expression of primary principles’. This resonates with af Klint’s own exploration in this series.

7. New Old Geometries

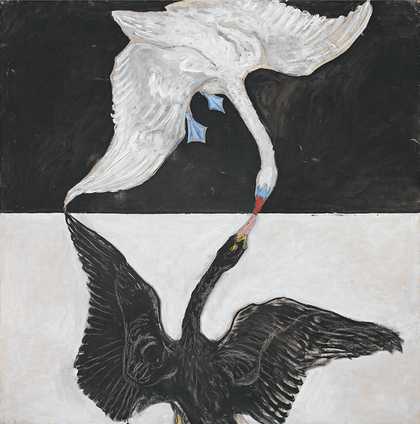

The Swan series dates from 1914, when af Klint was living in Stockholm and much of the world was consumed by the First World War. By this time, she claimed to no longer be directed by her spiritual guides. Across the series, there is a shift between figurative imagery and abstract forms. Two swans engaged in conflict, rendered in opposing black and white, metamorphose into a series of interlinked cubes. The series marked a development in af Klint’s visual language from organic tendrils, spirals and symbolic forms to increasingly geometric shapes and planes of solid colour.

Af Klint would have encountered the notion of an invisible, fourth dimension of space through Theosophy and the work of a prominent member and philosopher, Rudolf Steiner. Her depiction of dematerialised forms, such as the see-through cubes, suggest her familiarity with these theories. Such ideas largely disappeared after Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity was popularised, transforming understandings of space and time.

The swan was a popular occult symbol of unity, discussed extensively by leading Theosophist Helena Blavatsky in her book The Secret Doctrine, which af Klint owned. The visual arc towards an eventual state of reconciliation in The Swan might have been af Klint’s response to political and social upheaval. She said, ‘where war has torn up plants and killed animals there are empty spaces which could be filled with new figures, if there were sufficient faith in human imagination and human capacity to develop higher forms’. Af Klint continued to use geometry in her search for ‘primordial images’ and to convey her philosophical message of unity in Series III and Series V.

8. Space and Rhythm

From 1914, Mondrian was interested in how space could be brought to life through the experience of painting. This room features some of his neo-plastic paintings, comprising horizontal and vertical lines, primary colours and grey, white and black.

Mondrian developed his theory of neo-plasticism – a visual language of ‘pure relationships’ – around 1920. He had abandoned any form of symbolism: his paintings became irregular grids and are often described as ‘jazz rhythms’. Before this, in 1918, he had discovered the spatial impact of the lozenge shape, which appears in much of his later work such as Picture No. III: Lozenge Composition with Eight Lines and Red, featuring double and triple lines. He referred to ‘dynamic equilibrium’ to explain how a composition is produced through spatial relationships of lines and colour planes.

Mondrian intended neo-plasticism to function as a pictorial language. He set out to reduce painting to its basic principles, removing individual aspects (which he called ‘tragic’) to express the ‘universal’. As a result, his work is often regarded as detached from life, but this oversimplifies the complex relationship his paintings have to the world. To Mondrian, the ‘deepest essence of art’ always remained the same; it was to make ‘the beauty of life’ visual, tangible and, most of all, perceptible.

9. Confluences

Much of this room is dedicated to a series that af Klint named Parsifal, which may be titled after the opera by Richard Wagner. The subtitles of individual works include ‘Ether’ and ‘Astral’. These are terms used by leaders of the Theosophical Society, Annie Besant and Charles W. Leadbeater. In their books, Thought Forms and Occult Chemistry, they refer to unseen forces that can only be accessed by gaining higher consciousness. Af Klint’s occult beliefs became a framework for her to experiment beyond the limits of her artistic training.

Af Klint created Parsifal in 1916 in her studio on the island of Münso, Sweden. She had become less interested in the city of Stockholm, despite its growing international art scene. She imagined building a residential and research community on Münso, where she and friends could spend years researching plants, animals and minerals.

Two later works by Mondrian are also displayed. Composition with Yellow Lines exemplifies Mondrian’s neo-plastic art. The relationship between horizontal and vertical lines evokes a grid that expands beyond our field of vision, suggesting an all-encompassing environment. Rose in a Glass is painted on a brilliant yellow background with the delicate rhythms of the petals delineated by a soft, radiating line. While Mondrian was ambivalent towards his flower works and scholars have suggested they were largely a commercial venture, he continued to produce them late into his career, even without a commission.

10. The Future

My mission, if it succeeds, is of great significance to humankind. For I am able to describe the path of the soul from the beginning of the spectacle of life to its end.

Hilma af Klint, 1917

The Ten Largest are part of The Paintings for The Temple, a body of works af Klint believed was commissioned by her spiritual guides. They represent the stages of life, from childhood to old age. Af Klint animates this cycle using organic motifs and abstract geometries. For example, the snail is reflected in the logarithmic spiral – a form deeply connected with processes of growth and evolution. Botanical forms morph into abstract ones as the imagery veers from microscopic to cosmic.

Af Klint dreamed of building a temple in the form of a spiral, where her paintings could be hung together as a ‘beautiful wall covering’. To ascend through the temple meant to move towards a higher state of being. Despite their large scale, af Klint worked quickly to produce The Ten Largest in a few months in 1907. She was completely overturning contemporary conventions of artmaking in terms of scale, colour and form.

Af Klint and Mondrian used art to make laws of nature visible – laws that Mondrian believed underpinned the natural environment as well as architectural design. Neo-plasticism was a visual model for an equitable and harmonious future. Both artists believed their visual languages would be better understood by generations to come. In fact, af Klint stipulated that many of her works should not be shown for twenty years following her death. In their own ways, they challenged the separation between art and life. Art became their process for reflecting on universal patterns, and a way to make visible the fragile connectedness between forms of life.

The Ether

You are now in The Ether. Taking its title from the early nineteenth century view that an invisible energy connected everything visible, this is a place where discoveries, beliefs and creativity converge. Explore objects and images reflecting the cultural context and creative circles that surrounded af Klint and Mondrian in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These materials reveal af Klint and Mondrian’s deep-rooted connection to ecology – that is, an immense but fragile network of connections between all living things. They show their workings out and ways of thinking through nature that underpin their abstract paintings.

During their lifetimes, popular conceptions of the world were shifting, as significant discoveries and developments from various fields of knowledge came to public attention. This room asks how such shifts were taken up by the artists and their peers – how art intersected with other cultural, scientific and spiritual inclinations of the day.

The room is structured by three interconnecting themes that you can view in any order: Vegetal Knowledge, Inner Lives, and Invisible Worlds. Sketchbooks, notes and books belonging to the artists are presented amongst resonant objects from other spheres. It is a visualisation of the ideas circulating in the ether – the work of scientists, spiritual guides and cultural thinkers whose impact extended beyond their fields to cross-pollinate the thinking of others. Writing and images related to nature, science, spirituality and art shaped af Klint and Mondrian’s artistic evolution and broader worldviews. Artworks by their close contemporaries are also displayed, reflecting shared interests in these areas of knowledge.

Inner Lives

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries marked a significant shift in concepts of spirituality as a reaction against materialism. The religious belief in the world’s creation by a single God had been destabilised by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, set out in On the Origin of Species (1859). Theosophy, an eclectic spiritual movement, absorbed evolution into its ideology. Many promoters of occult beliefs drew on scientific and technological discoveries of the time. These spiritual movements, often enigmatic, were seen by some to be at the cutting edge of what it meant to be modern. Theosophy was concerned with the idea that everything in the universe is interconnected. Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, described an invisible energy underlying everything.

Invisible Worlds

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, several scientific and technological developments changed the way we see the world. X-rays, discovered in 1895, made solid matter appear transparent, revealing previously invisible forms. This raised fundamental questions about the existence of worlds imperceptible to the human eye. The development of wireless telegraphy in the late 1890s, based on the discovery of electromagnetic waves in 1888, suggested empty space was filled with vibrating waves. In the early twentieth century this mysterious, invisible substance termed the ‘ether of space’, was discussed in popular literature, and occult journals. Such new ideas on the possibilities of dimensions beyond perception, as well as reformulations of the relationship between space and matter, provided rich material for many artists.

Vegetal Universe

The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus developed a system of classification which encompassed plants, humans, animals and minerals. His influential published works demonstrated new ways of ordering all plants and included botanical illustrations of specimens imported from their native regions by European colonisers. Studies of organic forms by botanists and biologists, such as Ernst Haeckel, provided inspiration for artists. For example, the organic curves and sinuous lines of the art nouveau movement were clearly inspired by botanical illustration. Ideas of growth and plant life may also indirectly contribute to our understanding of an artwork itself as a living organism.