Hilma af Klint

Group IX / SUW, no. 1. The Swan 1915

Oil paint on canvas

150 × 150cm

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

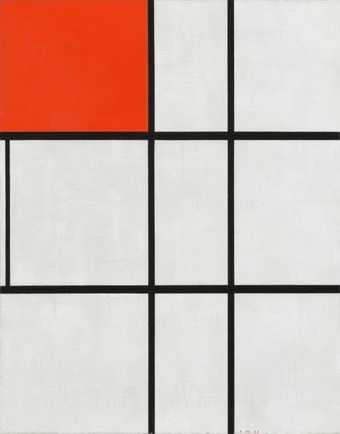

A visitor to Tate Modern in 2020 might have been surprised to find a work by Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), the Dutch pioneer of abstraction, hanging not alongside his avant-garde peers but opposite a ‘cabinet of curiosities’ by the Bombay-born artist Atul Dodiya (b.1959). While Mondrian’s Composition B (No.II) with Red 1935 is composed in his signature geometric style, Dodiya’s Meditation (with open eyes) 2011 is a miscellany of sorts. It includes a small painting depicting a black circle – a take on the Russian avant-gardist Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square of c.1915 – set alongside objects honouring, in turn, the non-violent activist and leader of the Indian National Congress, Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi, the painter Bhupen Khakhar and the poet and polymath, Rabindranath Tagore, as well as several representations of the Hindu deity Shiva.

Piet Mondrian

Composition B (No.II) with Red (1935)

Tate

In two of the three cabinets, Dodiya includes small paintings in Mondrian’s instantly recognisable style. These, Dodiya later explained, relate to his visit to Tate Modern in 2001, shortly after the museum opened, when he appeared in the exhibition Century City. Dodiya’s stay in London coincided with catastrophic earthquakes in his native Gujarat, a state on India’s western coast. Encountering Mondrian’s Composition B (No.II) with Red for the first time, Dodiya saw in the pronounced craquelure of the painting’s well-aged white surface a powerful evocation of the ravaged landscape of his homeland.

In Dodiya’s reframing, he promptly undid Mondrian’s – and art history’s – sustained efforts to disassociate abstraction from its origins in landscape. Meditation (with open eyes) locates Mondrian, as seen from a contemporary perspective, in a transnational and transhistorical network of associations, returning his ‘pure abstraction’ to the earth.

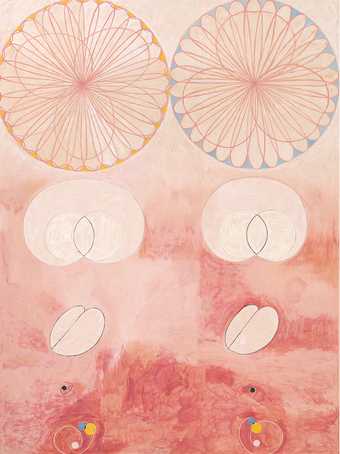

Hilma af Klint

Group IX / SUW, no. 19, The Swan 1915

Oil paint on canvas

148.5 × 152 cm

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

All exhibitions sit in complex relations to time; we see the past from the vantage point of the present. Our ‘now’ is rightly full of contested histories, and responses to new urgencies and heightened existential anxieties. These are reflected in a contemporary art scene that everywhere defies its own boundaries and – like Dodiya – seemingly plays fast and loose with art-historical narratives. Which leads us to Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life, an exhibition that could only take place in 2023.

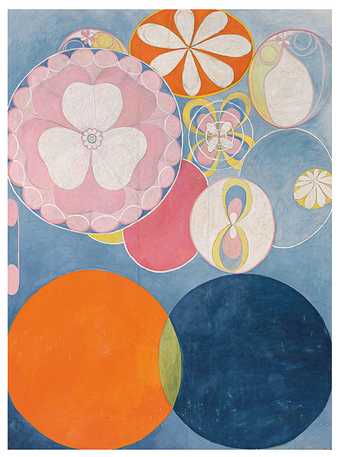

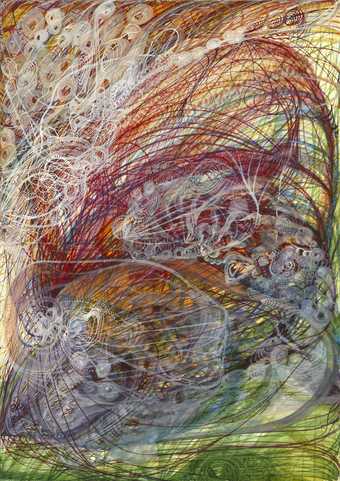

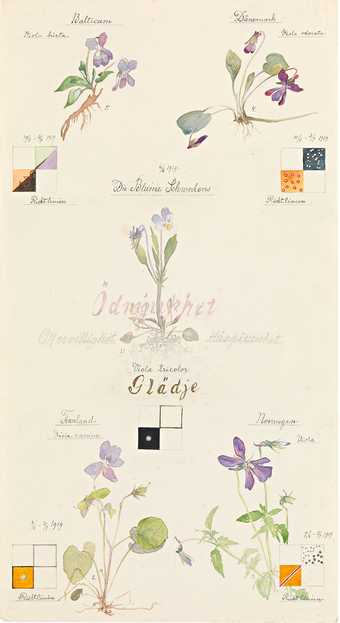

Mondrian and the captivating artist Hilma af Klint both came of age in an already well-connected world. They were born within a decade of each other in Western Europe – Mondrian in Amersfoort, the Netherlands, Hilma af Klint in Stockholm, Sweden – and had much in common. Both were classically trained artists, their practices rooted in the observation of nature and landscape painting. Their early, technically accomplished drawings of plants demonstrate parallel interests in close observation, implicitly referencing contemporary advances in taxonomies of botany, while also recalling the long history of exotic plant extraction and cultivation in Europe’s colonial history. They also shared a deep interest in mystical and spiritual belief systems. Both became members of the Theosophical Society – an occult movement predicated on the belief in a deeper spiritual reality – and they were ardent followers of anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner, who believed, among other things, in the human ability to contact other spiritual realms. Af Klint and Mondrian’s intense preoccupation with the natural world – their interest in notions of growth and change for example – suggests a precocious and nuanced understanding of ecology. This interest extended, via Steiner, into the ‘cosmic’ connections between life on Earth and the transcendental, linking humanity and nature within a single holistic system.

Hilma af Klint

Violet Blossoms with Guidelines Series I 1919

Watercolour, graphite and metallic paint on paper

50 × 28.6 cm

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

This was an era when science and spirituality – and art – were seen as entwined. The rise of occult science and the popularisation of Theosophy was partly in response to the technological and scientific changes that were disrupting established understandings of planetary and human history, notions of space and time, and the nature of matter itself. Occult theories and practices afforded a context and method for the absorption of phenomena that were, at that time, almost as incomprehensible to professional scientists as they were to lay people. Alongside an explosion of interest in astrology (Mondrian himself was an adherent), this period also saw a popularisation of science fiction, a form of writing exceptionally effective in dealing with the incomprehensible, as well as in transporting readers seamlessly through space and time to otherwise unimaginable futurities. Sweden’s first writer in the genre was Claës Lundin, whose Oxygen and Aromasia, published in 1878, was set five centuries after its writing, in the year 2378.

Art history has been less imaginative in making such spatial and temporal leaps. We still struggle, it seems, to accommodate af Klint and Mondrian within the same ‘art world’. Mondrian’s career, after all, was shaped by modernism, and the artist helped to shape it in turn. Wassily Kandinsky, Malevich and Mondrian were the three artists generally credited with inventing pure abstraction, and thereby revolutionising the history of art. Mondrian has been the subject of hundreds of monographic shows and remains a towering presence in histories of the avant-garde; he is one of the most famous artistic brands on earth. No wonder, then, that there has been such resistance from cult followers to allow a detour from modernism’s origin story, even a century after its birth.

Hilma af Klint

Group 4, No. 9. The Ten Largest, Old Age 1907

Tempera on paper lined on canvas

320 × 238 cm

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

By contrast, af Klint was overlooked by art history during her lifetime. Her wider reception came 40 years after her death, in the 1980s, by which time our ‘ways of seeing’ had profoundly changed. Yet, while other female artists over recent decades have been assimilated into the (male) canon, it seems as though af Klint’s belated arrival has proved especially problematic to modernism’s gatekeepers. Her introduction to the main stage was via curator Maurice Tuchman’s exhibition The Spiritual in Art (1986), a presentation of almost a century of abstract paintings made between 1890 and 1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Gemeentemuseum (now Kunstmuseum Den Haag). A monographic exhibition of af Klint’s work, curated by Åke Fant, followed three years later at Moderna Museet in Stockholm. No doubt, for many critics, Fant’s chosen subtitle, ‘Occult painter and abstract pioneer’, was simply a contradiction in terms: after all, less than a decade earlier, the eminent and influential critic Rosalind Krauss confessed to finding it ‘indescribably embarrassing to mention art and spirit in the same sentence.’ It was to be a further 25 years before af Klint was afforded a comprehensive survey show outside of Scandinavia, at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 2019.

Meanwhile art historians of abstraction continued to resist her inclusion in the official history. Her associations with spiritualism and her rich and varied vocabulary of abstract and symbolic forms had been deemed out of kilter with the formal austerity of her better-known contemporaries, and so she has remained steadfastly excluded from major surveys and shows. For instance, in Inventing Abstraction, the 2012 landmark exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the curators selected artists using vectors of artist-to-artist relationships, asserting that ‘abstraction is about relationships’ and therefore reinforcing, it seems, an exclusive approach to art history, as well as a Euro-American framing, that now feels outdated. Of course, af Klint was left out.

Hilma af Klint

Eros, No. 5 1907

Oil paint on canvas

58 × 79 cm

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life takes a different stance. It is shaped by new ways of understanding the world and history, and it suggests that artists and artworks can co-exist and connect through circulatory systems of ideas and beliefs, or the ‘intellectual currents of the time’. In this recovered context, af Klint no longer feels like a marginal figure, nor Mondrian necessarily so mainstream.

The years covered in this exhibition, from 1900 to 1922, span a period in which two contradictory notions of time co-existed: the slow, deep time of Darwinian evolution and the fast time of Western modernity. Among the plethora of inventions, revelations and innovations that define those years, two staging posts in the pre-history of our 21st-century predicament went unnoted and unconnected. One was the first documented use of the term ‘biological diversity’ in 1916. The other was the creation of the first model of climate change to link increased levels of CO2 with global temperature rise in 1896. A century later, we are finally beginning to understand and acknowledge the planetary implications of their entwining.

Piet Mondrian

Composition in Line, Second State 1916–17

Oil paint on canvas

108 × 108 cm

©2022Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Kröller-Müller Museum

*

Cop26, the UN Climate Conference that took place in Glasgow in 2021, included a special nature day. This was the first time that connections between biodiversity and climate crisis in the world’s eco-systems were finally recognised at an international level, an acknowledgement of decades of growing advocacy from scientists and activists. Artists, writers and musicians now grapple with the implications of a scientifically proven Anthropocene epoch, arguing that we need new ways to understand our world and to safeguard our future.

Joseph Beuys, Cecilia Vicuña and Anicka Yi, artists whose work collectively spans half a century of growing eco-awareness, have all pursued utopian agendas in the light of climate emergency, whether drawing on ideas of social and political transformation, harnessing indigenous belief systems or exploring futuristic science and technology. And it is possible to hold these diverse positions together, if we accept that knowledge is itself a kind of ecology enriched by a diversity of conversations.

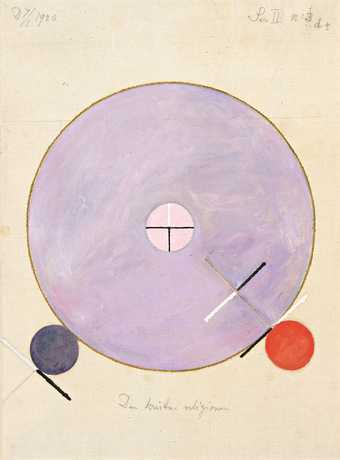

Hilma af Klint

No. 3d, The Christian Religion 1920

Oil paint on canvas

37 × 27 cm

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

Any dip into the exhilarating recent offerings of ecologically aware thinkers – whether biologists, philosophers or writers – charged with confronting the existential challenges of our times, reveals a gathering urgency to identify how to do this ecological thinking. For example, two recent works, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make our Worlds, Change our Minds, and Shape our Futures (2020) by Merlin Sheldrake and Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (2021), both suggest, in different ways, that we need to weave together hitherto disconnected disciplinary practices. The writer Jeremy Lent has described a ‘web of meaning’ binding secular, scientific and spiritual thought into a new world view. And feminist theorist Donna Haraway, in her book Staying with the Trouble (2016), argues that we need new relationships with each other and the planet; that we must make ‘oddkin ... unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles’ to be truly present.

In making exhibitions of historic figures, the urgency, as these individuals recede ever further from a rapidly changing present, is to find a fit between the ‘period eye’ of the artist’s own time and the world view of our own, in a form of rewilding of the monoculture of art history. Mondrian and af Klint’s own interests in ecology – and ecological thinking – represent a way of viewing both art and the world as part of a vast and complex organism or system.

Piet Mondrian

Evening; The Red Tree 1908–10

Oil paint on canvas

70 × 99 cm

©2022Mondrian/Holtzman Trust. Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag

Ecological thinking – the study of relationships between organisms and their environment – offers us an expanded framework, rich in metaphor, in which to express complex ideas, in art as in the natural world. Our understanding and appreciation of either af Klint’s or Mondrian’s devoted and lifelong exploration of forms of life, from the microscopic to the cosmic, can be enriched by examining their generative entanglement with each other: two towering artists deeply enmeshed in the ‘ethereal’ world view of their time.

Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life, Tate Modern, 20 April – 3 September. Presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. Exhibition organised by Tate Modern and Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Curated by Frances Morris, Director, Tate Modern, Nabila Abdel Nabi, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, Briony Fer, Professor, University College London, Laura Stamps, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Kunstmuseum Den Haag and Amrita Dhallu, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. Supported by The Af Klint and Mondrian Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members.