Room 1: The Invention of Dora Maar

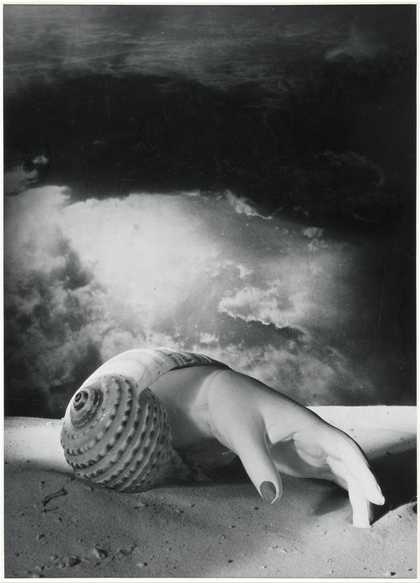

Dora Maar Model in Swimsuit 1936 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles © Estate of Dora Maar / DACS 2019, All Rights Reserved

Dora Maar’s career spanned mediums, techniques and much of the 20th century.

Born Henriette Théodora Markovitch in 1907, during her childhood she preferred to be called Dora. Raised between Argentina and France, her mother owned a fashion boutique and her father was an architect. Initially she was educated in the applied arts and painting at Paris’s most progressive art schools. In her early twenties, encouraged by mentors who saw her talent, she decided to pursue photography.

In 1932, a public bulletin announcing the opening of her first studio marked her transformation from Henriette Markovitch, ‘artist-painter’, to Dora Maar, photographer. Within just a few years she built a photographic practice of remarkable variety. She took assignments in fashion and advertising, travelled to document social conditions and made wildly inventive images that came to occupy an important place in surrealism.

By the end of the 1930s, Maar had returned to painting. She would devote herself to this medium for the remainder of her life. Remembered mainly for her surrealist photographs and photomontages, it is only since her death in 1997 that the full breadth of her output has begun to be recognised.

The exhibition opens with portraits made by Maar, or taken by photographers close to her. It continues to trace her long career and the political context, professional opportunities and personal networks that shaped her decisions at every stage.

Room 2: On Assignment

Maar’s decision to become a photographer was in one sense practical. Commercial assignments offered greater stability than fine-art painting. But it was also aspirational. As a woman from a bourgeois family, she did not have to pursue work out of financial necessity. Maar, however, belonged to a generation of women photographers eager to seize the professional opportunities created by the interwar boom in advertising and the illustrated press.

In 1930, Maar shared a darkroom with photographer Brassaï (1899–1984) and assisted fashion photographer Harry Ossip Meerson (1911–1991). The following year she set up a studio with director and film-set designer Pierre Kéfer at his family home just outside Paris. Specialising in portraits, nudes, fashion and advertising, the studio was as prolific as the artists were well connected. Maar called this her ‘worldly period’ on account of their glamorous clientele.

Though many prints during their collaboration were signed ‘Kéfer–Dora Maar’, Maar was usually the sole author. When their partnership ended around 1935, Maar established her own studio in central Paris and took independent commissions.

Innovation characterises Maar’s work from this period. Whether through staging, experimentation in the darkroom, or collage using simple scissors and glue, her images declare a break with reality.

Room 3: On the Street

Beyond the four walls of the studio, 1930s Europe was in the worst economic depression of modern times. It was in these devastating social conditions and fraught political climate that photographers developed the documentary mode, exploring what it meant for the camera to bear witness to hardship.

Like many of her peers, Maar felt compelled to record the lives of society’s most disadvantaged. In 1933, without being commissioned by a newspaper or magazine, she travelled alone to the Costa Brava in Catalonia, north-eastern Spain. In 1934 she went to London. On the outskirts of Paris, she photographed ‘La Zone’ – an undeveloped area that was home to around 40,000 citizens.

Political convictions motivated these projects. ‘I was very much on the left at 25… not like now’, she later said. Maar signed her name to Appel à la lutte (Call to the struggle), the manifesto launched by surrealist poet André Breton (1896–1966) and screenwriter Louis Chavance (1907–1979) in response to riots by the extreme far-right. She also participated in the anti-fascist movement Contre-Attaque (Counter-attack) he led with philosopher and social critic Georges Bataille (1897–1962). In this same revolutionary spirit, Maar recorded the rehearsals and performances of the leftist theatre troupe Groupe Octobre.

Room 4: The Everyday Strange

As Maar’s political leanings brought her close to the surrealists, their shared outlook soon expressed itself in her work. Led at first by poets André Breton and Paul Eluard (1895–1952), among others, the surrealist movement aimed to transform human experience. Refusing the constraints of modern society, artists and writers advocated for intellectual, as well as social, revolution. At the movement’s heart was a rejection of the rational in favour of a vision that embraced the power of the unconscious mind.

The chronicling of Paris occupied a special place in the surrealist imagination. Inspired by Eugène Atget’s (1857–1927) images of ‘Old Paris’, photographers found the potential for the marvellous, mythic and strange in the historic city. ‘Nothing is as surreal as reality itself’ claimed Maar’s friend Brassaï.

In contrast to her documentary photography, in these photographs Maar used crops and dramatic angles to offer a disorienting view of the city. They evoke the immediacy of the chance encounter so prized by the surrealists.

Room 5: Surrealism

It was not at first obvious to the surrealists how photography could fit into their movement. Whereas they emphasised the spontaneous and subjective, photography had long been prized as a tool for factual recording.

The answer came in the medium’s precarious relationship to reality. If extreme close-ups and unexpected contexts could render the familiar strange, photomontages could create new worlds altogether. Maar’s approach and preferred themes – the erotic, sleep, eyes and the sea – aligned perfectly with surrealist ideas. Maar became one of the few photographers included in the major surrealist exhibitions shown during the 1930s in Tenerife, Paris, London, New York, Japan and Amsterdam.

As friendships and romances inevitably developed, artists, writers and poets expressed their mutual admiration and devotion through their work, as in the portraits Maar made of her close circle.

Room 6: In the Darkroom and the Studio

In the winter of 1935–6, Maar met Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). While she was at the height of her career, he was emerging from what he later described as ‘the worst time of my life’. He had not sculpted or painted for months.

As artists often working in close quarters, the couple pushed one another into new creative territories. Maar taught Picasso the complex cliché verre technique – a method combining photography and printmaking that had intrigued him for years. Although no stranger to taking photographs, he was not experienced in darkroom processes.

Picasso, in turn, encouraged Maar’s return to painting. While her photography was still included in exhibitions, by 1939 it was no longer where she channelled her energy. The flattened features and bold outlines of the cubist-style portraits she made at this time suggest Picasso’s influence. Her own style was yet to come.

Room 7: The War Years

From 11 May to 4 June 1937, Maar documented the progression of Picasso’s painting Guernica. He made this monumental work in response to the 26 April, 1937 aerial bombing of the Basque town, one of the worst atrocities of the Spanish Civil War. Until that point, Picasso had never been overtly political. With Maar, his outlook was changing.

A commission for the art journal Cahiers d’art, Maar’s complex project recorded the ways in which Picasso progressed the composition. In her images, we also see that he settled on a palette of black, white and grey, evocative of illustrated newspaper reports. It was ‘like an immense photograph … absolutely modern’ she observed.

Maar’s presence in Picasso’s studio impressed itself in discreet ways. Historians have long speculated that the electric lamp in Guernica was inspired by one of her studio lights, which Picasso used to illuminate the canvas as he worked. But Maar also stated that he borrowed the motif from a painting she made earlier that year – possibly The Conversation, on display in room 6.

From studies for Guernica came the ‘weeping woman’, the guise in which Picasso cast Maar over 30 times. Yet for Maar, this was not a portrait but a metaphor for the suffering of the Spanish people during the civil war.

Room 8: New Landscapes, New Surfaces

In 1942 Maar moved to another studio in Paris which became the setting for a new direction in painting. She made landscapes from the banks of the river Seine, a short walk from her front door, and tightly composed still lifes.

If Maar’s traditional subject matter suggests that she was interested in studying composition and form, her sombre palette conveys something more personal. Compounding the anxieties of life in occupied Paris, the first years of the 1940s brought a series of traumas: a protracted breakup, her father’s move to Argentina, the exile of close friends from France, and the sudden deaths of her mother and her friend Nusch Eluard (1906–1946).

From 1945, Maar divided her time between Paris and a new home in Ménerbes, in the South of France. Here, a new friendship with poet André Du Bouchet (1924–2001) led to creative collaboration. Her engravings for his anthology Mountain Soil 1956, signalled another change in technique. This time, she began to make gestural impressions of nature and the natural elements in ink, oil, and watercolour.

In abstract mark making, Maar had found a line of experimentation that would sustain her interest, in different ways, for decades to come.

Room 9: Return

Though photography still appealed to Maar in her later years, documenting the world outside did not. ‘The street has changed so much, don’t you think? It’s more extravagant … but at the same time it’s not interesting anymore, it’s banal’ she said in 1994.

More exciting, it seems, was what she could create in the darkroom. During the 1980s Maar made photograms by laying household objects or personal items onto photo-sensitive paper, or by tracing light across its surface.

The extent of Maar’s camera-less experimentation during this period was only revealed following her death in 1997. Forty-eight negatives and nine contact prints now held in the collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris further testify to her long-held interest in manipulation.

The world outside might have changed since she launched her career but, if only in her impulse to construct, deconstruct and to reinvent, Dora Maar had not.