Peter Kennard

Haywain with Cruise Missiles (1980)

Tate

Introduction

This exhibition offers an expanded view of British landscape art focusing on the early twentieth century until today. Traditional landscape painting is associated with idyllic rural scenes, which can express an artist's appreciation of nature and have helped form perceptions of the national identity. Ancient symbols embedded in the land, such as Stonehenge, are often imbued with mysterious or sacred meanings, becoming a mirror for individual and communal identities. The pictorial conventions of landscape art can also express the status of land ownership, themes of exclusion, or control over nature. Outside of painting, artists have turned to techniques including film, performance and installation art, showing how art can be made in and of the land, rather than by viewing it as a constructed ‘scape’.

Radical Landscapes interrogates the relationship between land, history, and identity. It explores themes of trespass, using art to explore the thresholds between public and private land, showing how these relate to our sense of identity and belonging. The enclosing of rural land and its perceived misuse has triggered protests throughout history, linking to broader arguments around civil freedoms alongside the long shadow of colonialism.

Against the context of the global climate emergency, nature is increasingly seen as something to protect and preserve, and many artists have produced work in parallel to the development of the modern environmental movement. All of this has provided fertile ground for artists and activists. Radical Landscapes presents the rural as a site of artistic inspiration and a heartland for ideas of freedom, mysticism, experimentation and rebellion.

Our Common Land

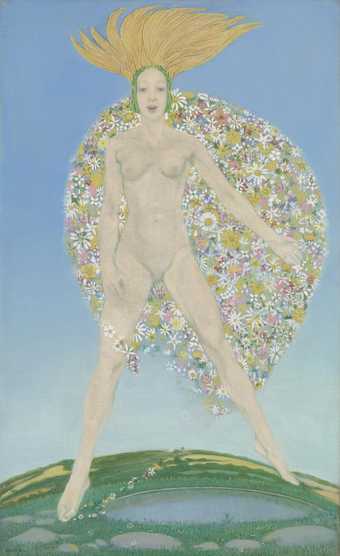

Art can provide ways of exploring our freedom to access and enjoy this ‘green and pleasant land’, as artists have explored themes around class, race, gender, community and nation. Landscape art can also shape our cultural and emotional response to rural sites. This is seen in the historical painting of John Constable, whose idyllic personal depictions of the natural landscape show a place of timeless leisure.

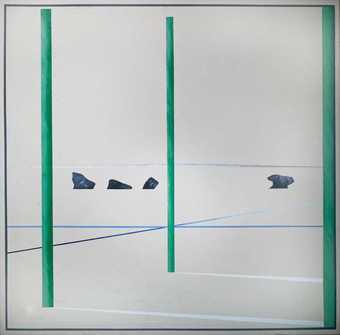

Yet throughout the twentieth century our desire to access and honour the rural landscape has triggered protests and campaigns of various kinds. This section explores right-to-roam trespasses, histories of the colonial countryside, to campaigns against the militarisation of common land. These show how artistic freedoms, as well as civil freedoms more broadly, are woven into accessing and protecting the natural landscape.

The act of trespass – the wilful intrusion of a person onto land owned by another – is rooted in the history of enclosure, or the appropriation of common land for private or commercial use. From the seventeenth to twentieth century, enclosure radically transformed the appearance and use of the land, depriving commoners of their historic rights of access. The requisition of land for military use, such as at Greenham Common in Berkshire, transformed rural areas into sites of conflict. The act of enclosure is also intrinsic, and ran in parallel to, the expansion of the British Empire. The colonial practice of taking land overseas and subjugating its peoples to exploit and control natural resources continues to shape British art, culture and identity today.

Land Use and Identity

These artists’ explorations of landscape show how our bodies and identities are deeply entwined and shape our sense of the world and of the self. Taken as a whole, we can see the give and take relationship with the land, how it enables self-expression yet also imposes social constructs and the literal boundaries that structure and govern our society.

Considering these artists’ relationships to the rural landscape over different times and regions offers a productive set of contradictions to explore. The rural offers nature as a refuge, a space to form and reform ourselves, somewhere to affirm identities or uphold ancient traditions. Art is used as a tool for connecting to the land; dance and performance become rituals of belonging; and painting, photography and installations reflect desires to align ourselves with nature.

Artists have often sought to expand notions of belonging to the land, beyond local and national borders. In reclaiming space, they foreground the multiple meanings we attribute to identity as a collective and individual category. Perhaps more than anything else, however, landscape itself has offered an apparatus for interrogating structures of power. These artists are engaging in artistic strategies as a way to make their own claims on how to define themselves.

Art in a Climate Crisis

From the mid-twentieth century to the present day, there have been artists working in parallel to the development of the modern environmental movement. Many environmental concerns are rooted in much earlier periods, such as the late nineteenth-century campaigns to protect nature and wildlife, as well as public health concerns around pollution and urbanisation. In the late 1960s, these ideas converged with increased awareness of climate change and atmospheric degradation, which transformed the ways in which art was made. Today the goals of the environmental movement extend globally to embrace issues including grassroots democracy, land justice, food insecurity and the dismantling of neo-colonial structures that exploit nature and people. These urgent priorities can be seen in the work of many international artists working today.

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of fresh air and accessible green space, showing the importance of rural landscapes and nature to physical and mental wellbeing. Taken together, these artworks ask us to consider our individual relationship to environmental issues and climate change. Not everybody identifies as an activist, but there is an increasing awareness of living mindfully and considering the decisions we make as consumers. Art can provide a vehicle for learning from and coexisting with nature and with each other.